The whirl of the blender at Real Fruit Bubble Tea intermittently drowns out the din of conversation in the East York Town Centre’s airy food court. It’s a busy place. People nurse coffee they brought over from the Tim Hortons that always seems to have a line-up by the mall entrance. Others eat food out of styrofoam containers from Chester Fried Chicken or Kandahar Kabab. The joyous shrieks of kids streaming in from the elementary school next door, the largest in North America, gives the bubble tea blender a run for who’s loudest. There’s lots of lingering; it’s a place to meet up and see who’s about, a place where nobody moves you along if you aren’t consuming something at all times.

A typical mid-sized, mid-century Canadian mall with shiny floor tiles in 1970s shades of brown, acoustic paneled ceilings, and fluorescent lights, East York Town Centre is well-worn and hasn’t been updated much. Nevertheless, the mall has become Thorncliffe Park’s de facto town square. “I think East York Centre is the one of the essential parts of the neighbourhood,” says Sabina Ali, chair and one of the founders of the Thorncliffe Park Women’s Committee. “It is like a recreation space, especially for the seniors.” There are indoor walking groups for seniors and women. During cold winters, parents pick their kids up from school and bring them to the mall, feeding them meals brought from home. Recently, Ali says, a fire in the mall shut it down for more than a week, leaving Thorncliffe residents without a place to gather. “It’s a really important place to meet with friends and neighbours and spend quality time talking while having a coffee or some food,” she says.

The mall’s draw as a social space isn’t a new phenomenon: for decades the Thorncliffe Bowlerama was a near-perfectly preserved subterranean recreation lair with both 5 and 10 pin bowling lanes and a bar in the middle. Throughout its history, discount department stores have acted as anchor tenants — the kind of big retailers malls covet, not only because they’re a draw unto themselves, but also because two or more anchors draw people between them, increasing circulation, browsing and spending. Sayvette, a now defunct Canadian discount department store, handed the discount baton to Woolco in the mid-seventies. That space later became a Zellers. And in 2013, the mall got an injection of retail star power when Target moved in, part of the American chain’s much-heralded expansion into Canada.

Malls like East York, with their varying mix of independent retailers and chains, are found all around Toronto. Eglinton Square in Scarborough, Sheridan and Centrepoint malls in North York, Albion Mall in Etobicoke, Lawrence Square, and the soon to be demolished Galleria Mall in the old City of Toronto all play similar rolls in their communities. When Target announced the closure of all their Canadian stores in 2015, however, many malls were left with enormous holes in their floor plans to fill. At East York, the upper two floors of a key anchor space were left empty. Then in 2016 the Bowlerama closed its doors too. Coupled with a new Costco big box retail location that has opened across the street, drawing more people away, the future of the mall might seem like it’s part of the “dying mall” phenomenon occurring across the United States, where once-prosperous malls have lost their anchor tenants, starving smaller stores of a critical mass of shoppers.

“People are coming to the mall anyway, to socialize and to shop, so why not bring all those services under one roof?”

At East York, the cheaper rents have allowed independent mom-and-pop shops to flourish, businesses that couldn’t afford the overhead of Toronto’s high rent main streets and more prosperous malls. In the tech industry this kind of space is sometimes called an “incubator” for innovative “start up” businesses, but here it happens under the radar of the rest of the city. But while the small spaces are ideal for individual ventures, vast anchor spaces are harder to fill. A Dollarama eventually moved into some of the main floor space, keeping the discount retail tradition alive, as did an A&W franchise, but there was still more space to fill. Enter the Flemington Health Centre (FHC) and The Neighbourhood Organization (TNO), two health and social service agencies that saw an opportunity to serve local residents in the languishing retail space.

“Maybe 5 or 6 years ago there was a recognition in the Thorncliffe community that there was a lack of comprehensive primary care,” says John Elliot, Executive Director of the FHC. Health care in the community was scattershot: there were physicians at walk-in clinics treating people, and others operating at independent offices, but nothing that looked after the long-term health of the community as whole, no central place that would promote social and physical health and illness prevention in the community as much as treating colds and pulled muscles. Since everyone was already at the mall, it was a natural place for a hub where all of this could be centralized and coordinated: a one stop shop for getting better and staying healthy.

Shopping and health care may not seem like natural partners, and a project on this scale hasn’t been tried in Toronto before. Can the hub, a blossoming public institution establishing itself in a privately run, for-profit retail environment, become the stable anchor the mall needs to carry on its role as Thorncliffe’s unofficial town square? More importantly, can this unique partnership help make the community a healthier place?

Within living memory of some Torontonians, Thorncliffe Park has gone from a rural landscape to the dense urban form that exists today. From 1917 to 1952, the grounds were home to the Thorncliffe Park Raceway, where horses competed on a plateau high above the Don Valley. As the region grew rapidly in the post-war years, the town of Leaside, a former municipality now part of Toronto, redeveloped the land into a then-innovative modern apartment neighbourhood that could house entire families, a living arrangement common in Europe. Initially marketed to young and upwardly mobile couples keen to start families, the yuppies of their day, the neighbourhood has since seen massive demographic changes that were not part of the original plan.

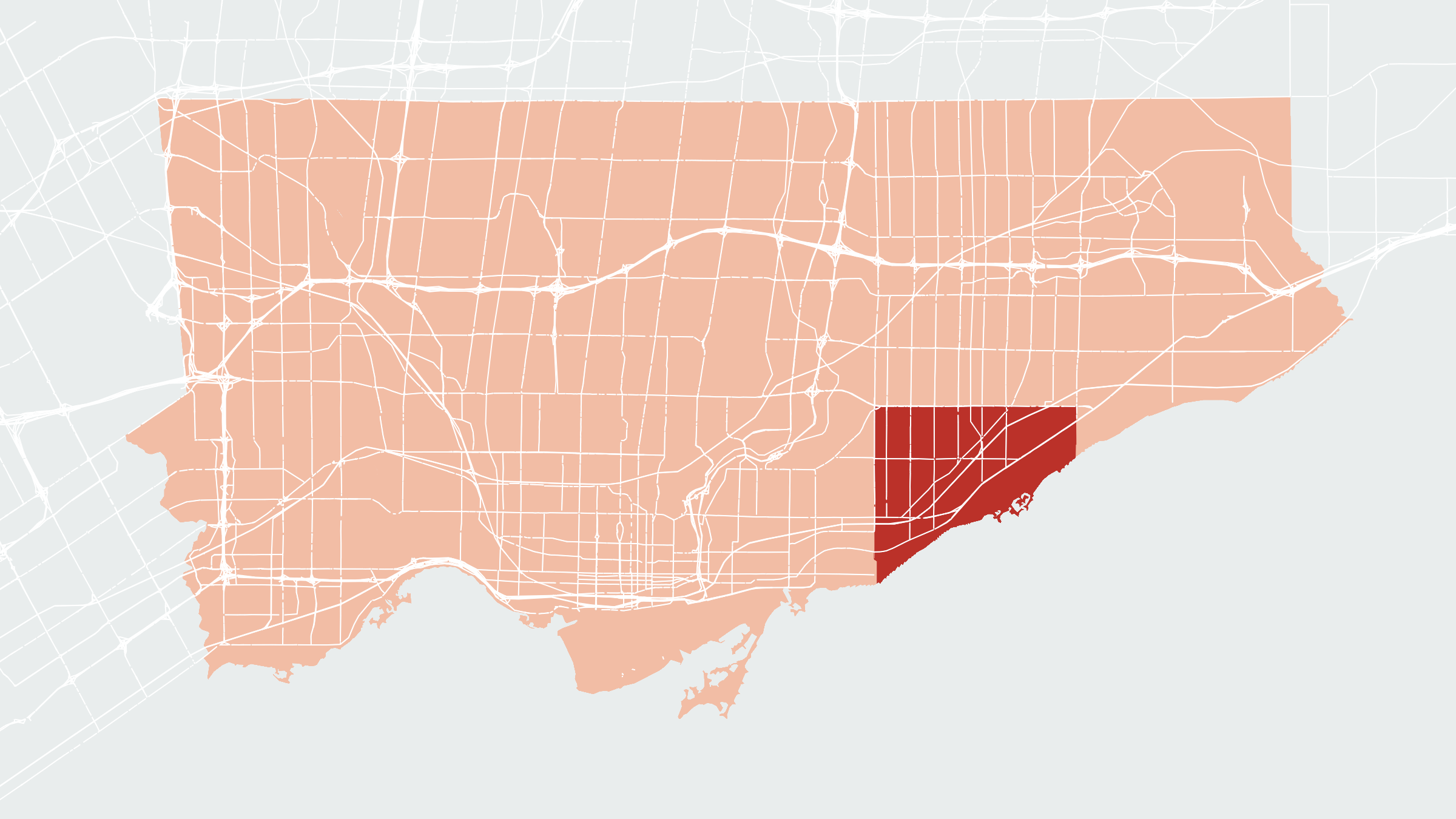

Over the years Thorncliffe has attracted newcomers, including a substantial number of recent Syrian refugees, drawn by the large apartments and slightly lower rents than those found in the city core. Today, Thorncliffe Park is one of the densest clusters of people in Canada and a “landing pad” neighbourhood for immigrants. Toronto’s multiculturalism mix is profound here: 71 percent of the population has a mother tongue that isn’t French or English, with Urdu speakers leading the way, followed by Gujarati, Persian, Tagalog and Pashto. Over 20,000 people live here, though it was designed for far fewer. It’s a young, family-oriented community, with 26 percent of the population under 14 years old.

Unlike most of Toronto’s family friendly neighbourhoods, which are generally made up of detached or semi-detached dwellings, in Thorncliffe housing is almost exclusively in large apartment buildings. Though Thorncliffe is located relatively close to the central part of Toronto and remains an imminently walkable neighbourhood, it’s somewhat geographically isolated, surrounded on the south and east sides by the lush and sinuous Don Valley and to the north and west by a light industrial landscape.

While bus service is good, many people don’t leave the area much due to the costs of travel, says Elliot. On a recent sailing excursion for neighbourhood youth, some of the kids had never ridden the subway before or seen Lake Ontario. “A lot of the kids, when they saw the lake said, ‘Oh, we didn’t know it was a sea next to the city,’” says Ahmed Hussein, Executive Director of The Neighbourhood Organization (TNO), a multiservice provider in the area that offers programs and assistance to newcomers, refugees and youth. “Even though they live in the city, they also don’t.”

Malls like East York don’t get the kind of attention newly landscaped parks and squares created by internationally renowned designers do, but they mean as much to the fabric of the city.

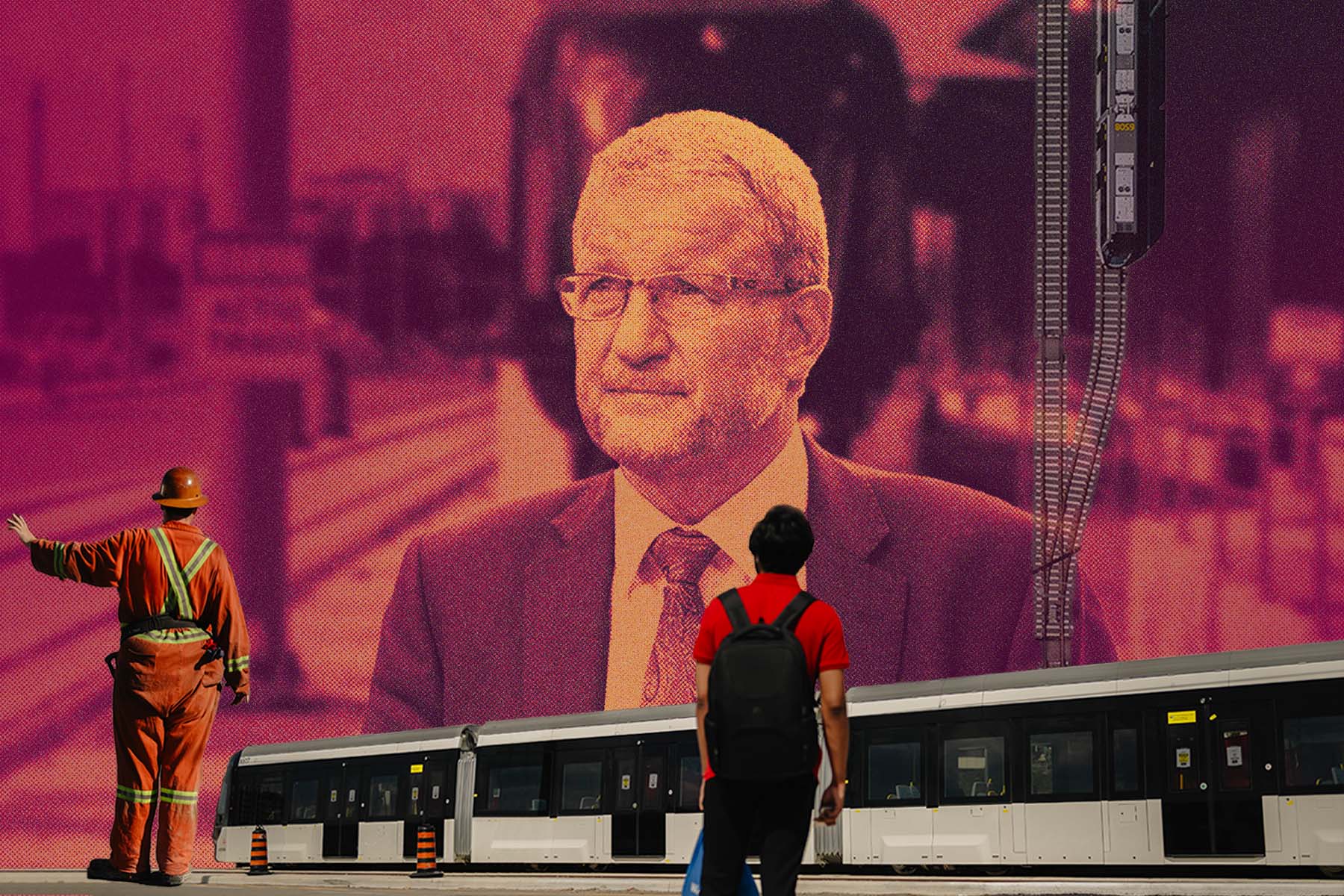

The health hub, then, offers a unique opportunity to treat a community where they live. For 40 years, the local health centre has operated out of Flemingdon Park, the community adjacent to Thorncliffe, providing a wide range of primary health care and health-related activities. In looking to address the needs in Thorncliffe Park, the health centre worked with the TNO to build something different. The model they created, called “Health Access Thorncliffe Park,” or HATP, is a hub that will bring together a variety of health and social services in the former Target store.

“That was the unique piece of the HATP model,” says Elliot. A visit to a walk-in clinic won’t happen in isolation. Instead, it will be integrated with the hub, so follow-up visits can be arranged and the patient’s long-term health prospects can be monitored and improved. Other partners have come on board, including the Toronto Healthcare Centre clinic located in the mall, a group of midwives, the local schools, Sunnybrook and Michael Garron hospitals, the United Way, the Toronto Central Local Health Integration Unit, and Toronto Public Health.

Social spaces will also be an important part of the hub. Elliot says they would like to create looser affiliations with neighbourhood groups and make room for members of the community who want to meet but often don’t have anywhere to go. The hub will also be an education centre to help newcomers navigate the sometimes complicated Canadian health care system and understand how to better take care of themselves. “It reduces the burden on the health care service overall,” says Elliot. “All the evidence says the more upstream you work, the more you work on health promotion and education, the less downstream costs you have in managing chronic illnesses.”

The ultimate plan is to provide primary health coverage, chronic disease management, newcomer services, mental health care, maternal reproductive care and newborn, child and youth services, all in the former department store. “No one who lives in Thorncliffe has to walk more than 200 meters to get to the mall,” says Hussein. “People are coming to the mall anyway, to socialize and to shop, so why not bring all those services under one roof?”

As plans proceed, pulling the many partners together and securing funding, the hub at East York Town Centre is scheduled to open in late 2020. “Having our hub in the mall will help the stability of the mall, which has nothing to do with our intended outcomes but it will be good for the community,” says Hussein.

Spending time in a mall may seem like a most insignificant pastime, but malls are places where community is built, especially in postwar, car-oriented cities where the traditional public realm, places you could bump into neighbours and where you might even promenade, either doesn’t exist or is substandard. That, and in winter Toronto gets rather cold. That may seem obvious, but judging by architectural and landscape renderings of new developments you’d be forgiven for thinking we live in a perpetual June as so little thought is given to cold weather public spaces.

A decade ago Don Mills Centre, a lower-tier enclosed mall in the middle of Canada’s first major post-war planned community, was transforming from a place that welcomed the mall walkers and seniors sipping coffee in the food court to a high-end outdoor mall. Locals mounted a campaign to save the dowdy mall from what ultimately became the Shops at Don Mills, a busy place, but one that caters to a different demographic than it previously served. Similarly, the planned residential and commercial development for the Galleria Mall that attracts a swath of Toronto’s west-side working class population has raised questions about what will happen to the community that currently uses it as their town square on a daily basis and on special occasions, like watching World Cup games on a widescreen TV set up in the central court.

True town squares are located in public space and owned by everyone while these malls are private, so the rules and management’s tolerance for the community life that is flourishing under their roofs could change arbitrarily. It’s a most provisional kind of community space, and one that isn’t sexy either. Malls like East York don’t get the kind of attention newly landscaped parks and squares created by internationally renowned designers do, but they mean as much to the fabric of the city. Health care isn’t particularly sexy either, nor should it need to be. What’s exciting here is the creation of a more permanent, public-focused space inside of a mall that, by chance, became the vital, if precarious, community space it is today.