Last August, Toronto Public Health generated a shortlist of schools considered to be “high-risk” based on COVID cases in the school’s surrounding community. This list contained 80 elementary schools in the TDSB and 36 in the catholic school board—nearly 15 percent of all public schools in Toronto. The high-risk schools received extra protections. For example, kindergarten classes at high-risk TDSB schools were capped at 15 students compared to 26 everywhere else.

The Local’s analysis shows that during the 2020-21 academic year, 89 percent of the nearly 800 public schools across the two boards had at least one COVID case; schools located in areas with more COVID simply had more. Those on the high-risk list had an average of 9.2 COVID cases per school—twice as many as the 4.6 cases at all other elementary schools. Of course, the difference would have been more stark had extra measures not been implemented at some of the high-risk schools.

Schools are not islands. Despite efforts to protect them from the circulating virus, the tiny invaders have proven themselves to be skilled at dodging our imperfect defences.

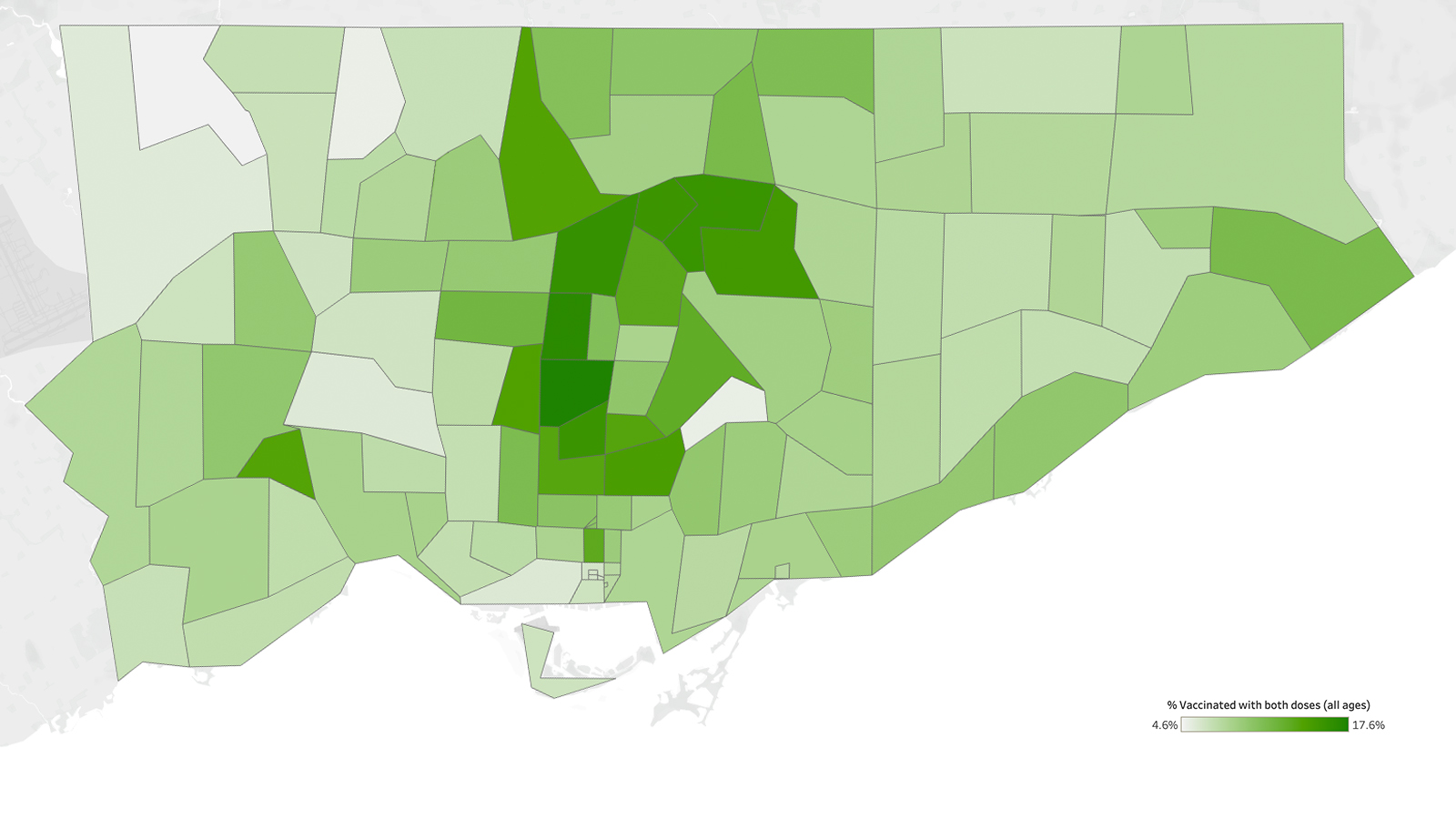

This year, students are going back to school in the face of a more transmissible variant and with fewer restrictions in the community. And while we have a new layer of protection in vaccines, coverage is uneven, with some areas of Toronto only 50 percent fully vaccinated. This sets up the conditions for Delta to preferentially exploit schools in under-vaccinated hot spots—conditions that could be tempered by having a list of high-risk schools where extra protections could be provided. But no such list exists this year.

Despite the familiar pattern of disparity across Toronto, much of the focus leading up to the new school year has been on having standard measures across the board, regardless of community risk: HEPA filters in every classroom, masks on every individual, confirmation of self-screening at every door. According to Ashleigh Tuite, an epidemiologist and mathematical modeller at the University of Toronto, while standard public health measures are critical, it’s also important to understand where the risks are highest and dial up the protections accordingly.

“If you’re in a community where there’s really, really low cases being reported or very low transmission, you don’t necessarily need all of those layers of protections that you would need in a school that has high transmission,” said Tuite.

The list of high-risk schools published last August—which did a decent job of foreshadowing things to come and helping to geo-target some of the countermeasures—isn’t available this time around. Toronto Public Health has not produced such a list, nor have the school boards.

“While TPH provided an analysis of communities with higher rates of COVID-19 and their associated schools, looking at a few other factors, throughout the year, the school boards themselves have been updating the analysis. Please connect with the school boards directly for further information,” said Vinita Dubey, Toronto’s associate medical officer health.

And the school boards?

“At this time, a similar list has not been created for this year,” said Ryan Bird of the TDSB.

“I believe TPH no longer considers schools ‘high risk’ but please feel free to reach out to them,” said Shazia Vlahos of the Toronto Catholic District School Board.

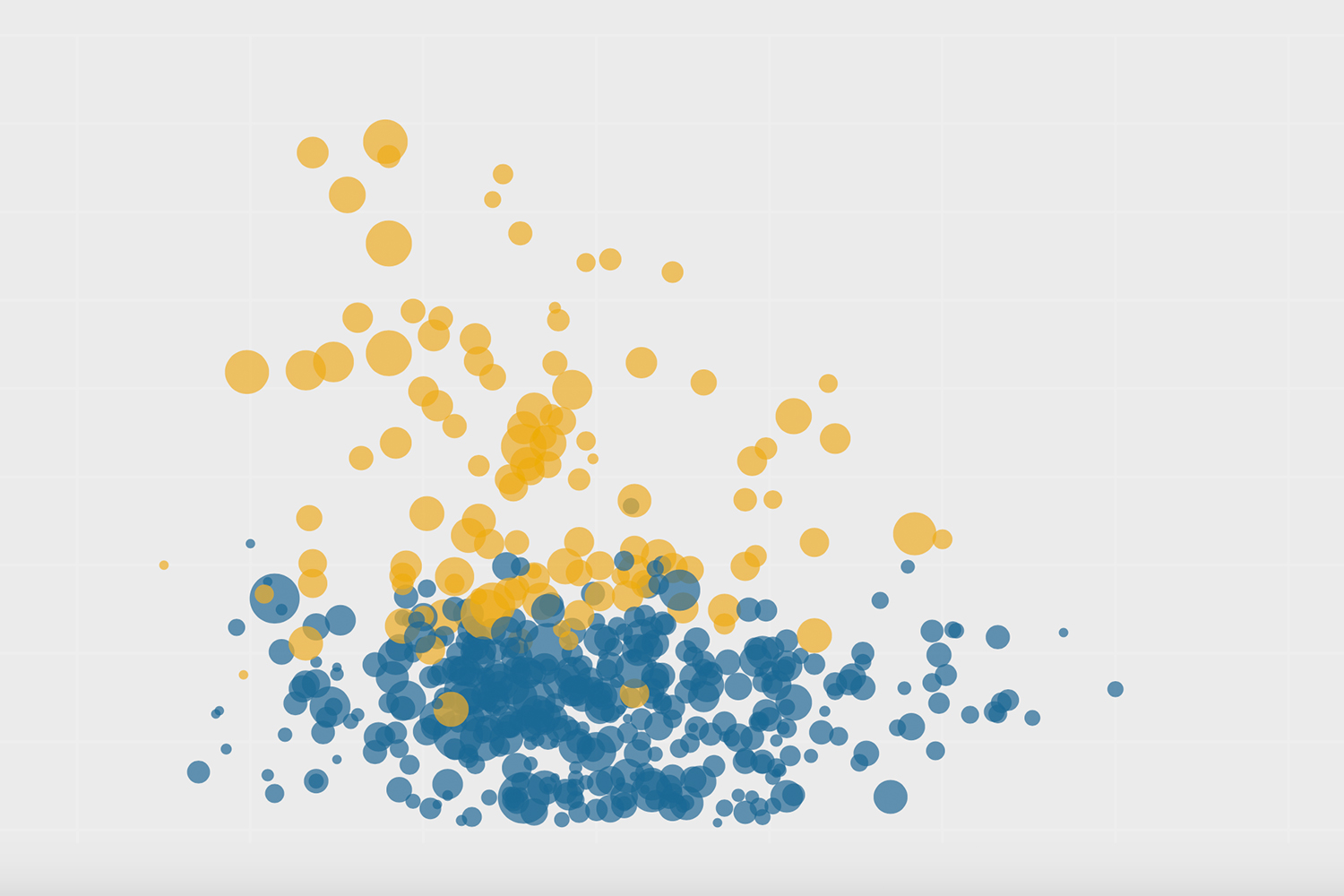

With Tuite’s input, The Local developed a list of high-risk schools for the upcoming school year. We compared the risk of COVID infections at the nearly 800 public schools across Toronto, taking into account the two major factors affecting transmission: the surrounding community’s propensity for infections and its vaccine coverage.

A community’s propensity for infection is measured by COVID cases per 100 people in a school area since the pandemic began, which is a reflection of the types of jobs people work in, along with other socio-economic factors that make them less or more prone to catching the virus. Unlike last year’s list, however, a neighbourhood’s propensity for infection is mitigated by its vaccine coverage, as measured by the proportion of the local population with one and two doses, taking into consideration vaccine effectiveness against the Delta variant among partially and fully vaccinated individuals.

Schools in areas with historically high rates of infection and where a large proportion of the population remains unvaccinated are considered to be at high risk. These areas include Thorncliffe Park (M4H), Jane and Finch (M3N), and Rexdale (M9V, M9W), among others. Just like how we rate hurricanes, these areas are classified as category 5 on our risk scale. Conversely, an area that historically hasn’t had many COVID cases, and where a high proportion of residents is vaccinated, is considered to be at very low risk. These areas include Leaside (M4G), Moore Park (M4T), and The Kingsway (M8X), among others. They’re category 1 on our risk scale.

The results of The Local’s analysis show that there are 157 schools in category 5 (the highest risk level). They include 129 elementary and 28 high schools (last year’s list did not cover high schools). There are strong similarities between the two years: 80 percent of the high-risk elementary schools this year also appeared on last year’s list. And like last year, the majority of the high-risk schools are located in Toronto’s northwest—a hard-hit region of the city that, this year, faces the double whammy of also being highly unvaccinated.

“I think the schools that are going to do poorly are the schools that have done poorly in the past,” said Tuite. “The fact that we’re seeing lower vaccination coverage in places that have been historically harder hit really drives home the fact that we need to be doing more about getting vaccines into the arms of people who will really benefit. So thinking about how you shore up vaccination in those communities is important.”

When Health Canada approved the Pfizer vaccine for use in people as young as 12 years old in early May, Brandon Zoras knew immediately that it was going to be a gamechanger for the 2021-22 school year.

Zoras is vice principal at Westview Centennial, a high school in the Jane and Finch area that had a number of disruptions throughout the previous school year due to positive cases. So when the vaccine was approved for high schoolers, Zoras quickly got on the phone with local politicians and vaccine teams. By the end of May, Westview was hosting its first pop-up clinic, open to anyone in the area.

“We held vaccine information nights with a public health nurse, and we had a school assembly about vaccines as well,” said Zoras. “We have something called school messenger, which would email all parents and all students in the school.”

Westview’s community outreach worked beautifully. More than 520 people showed up to get their shots, and nearly half were between the ages of 12 to 17, according to data from Toronto Public Health.

But behind the initial wave of enthusiasm, Zoras also saw early signs of the hesitancy that would eventually lead Jane and Finch to become the most under-vaccinated area of Toronto. Included in Westview’s mass emails was Zoras’s contact information in case parents or students had questions or concerns—basically giving him a hotline into discussions taking place in many living rooms around the school. There were obvious worries about side effects, or whether the mRNA could become a permanent part of your DNA. Zoras also saw tensions between some students and their parents, where a student might want to get the vaccine, but didn’t want to upset their parents.

“I think for teenagers, they have the right to go by themselves if they want, but there’s a lot of pressure coming from friends and family,” said Zoras. “So a lot of people kept telling us ‘I’m going to wait and see.’”

With just three weeks to go before school starts, the reality that vaccines might not be the magic bullet Zoras once hoped is starting to set in. The latest data from the not-for-profit research institute ICES show that only 63 percent of the Jane and Finch (M3N) population received their first shot, and only 52 percent have gotten their second—the lowest in Toronto. Barring some sort of vaccine mandate or other policies that will accelerate uptake, coverage rates aren’t going to change dramatically by the time school doors open.

With so many pockets of Toronto still highly unvaccinated and unlikely to improve to levels that are competitive with the Delta variant, Zoras wonders why we’re not reusing some of the extra protections deployed last year. For example, a year ago, Westview was able to have its students in cohorts of 15. “It looks like class sizes will be back to normal this year, which could be anywhere from 15 to 30 something,” said Zoras.

Larger class sizes in high-risk areas means that things are more difficult to control once there’s a positive case. “You really want to think about those cohorts and keep them as small as possible so that you can minimize disruption, and that you’re not shutting down an entire school because of exposure,” said Tuite.

But small class sizes means more teachers and space—resources that school boards don’t necessarily have. Last year, both the TDSB and catholic school board had to dip into their reserve funds in order to implement smaller class sizes in their high-risk schools. For the TDSB, this allowed them to set caps of 15 students for in-person kindergarten and 20 students for grades one through eight in high-risk schools. Catholic schools adopted a similar approach in schools where space allowed them to do so. Fewer individuals per room meant more space for physical distancing and better air. Even so, cases at high-risk TDSB schools were 64 percent higher than at other TDSB schools. Among Toronto’s catholic schools, the difference was 130 percent.

According to Tuite, smaller class sizes isn’t the only way to have a risk-based approach. “In a school in a community where you’re seeing lots of cases, you would potentially want to use things like rapid testing to get a better handle on what’s going on and to get things back under control,” said Tuite. In fact, just about every COVID precaution could be dialled up in high-risk schools: more onsite vaccine clinics, more community and family outreach, better ventilation, more vigilance.

With a looming fourth wave and the planning window quickly closing, it’s no wonder parents, students and teachers are nervous if not angry at the prospect of yet another year of uncertainty and repeated disruptions. But like much of the pandemic thus far, the toll won’t be felt equally across Toronto’s schools. A one-size-fits-all approach hasn’t worked at any point of the pandemic, for anything. Taking that approach to schools could mean more closures, disruptions, and illness at the city’s most vulnerable schools.

Correction—August 25, 2021: The original article indicated that only the TDSB implemented smaller class sizes in its high-risk schools last year. This has been corrected to indicate that the Toronto Catholic District School Board adopted a similar approach in schools where space allowed them to do so.

The Local’s ongoing vaccination coverage is made possible through the generous support of the Vohra Miller Foundation.