The students at York Memorial Collegiate Institute saw the chaos of this year coming long before anyone else did. Instead of being heard, they’ve spent much of the last two months being blamed for the breakdown of their school.

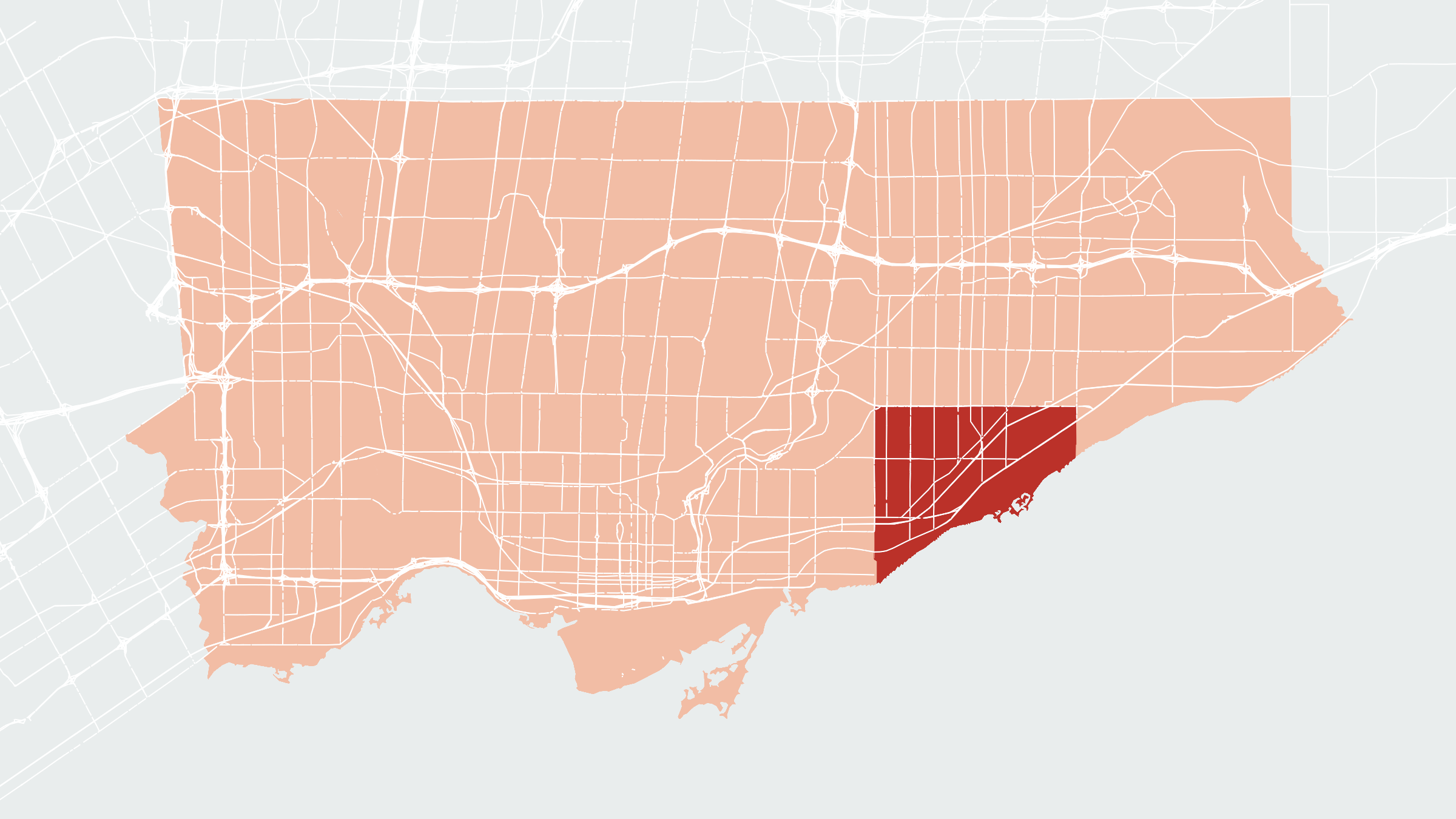

In 2019, a six-alarm fire ravaged the old York Memorial school building in Keelesdale, leaving the high-schoolers in search of a new home. Two weeks later, York Memo students were temporarily relocated to George Harvey Collegiate Institute—the 500-strong student body ten minutes down the road, seen by some as York Memo’s long-time rival—for the last couple of months of the school year. Chaos ensued. Students from the two schools fought, overcrowded classes were taught in hallways and closets, cafeteria lines got too long for people to buy their lunches, students’ commutes home took hours. The following year, the students were moved to Scarlett Heights Entrepreneurial Academy, a shuttered school building a 40-minute bus ride away in Etobicoke.

Two years later, when the students were polled about whether they supported the idea of merging schools with George Harvey permanently, they could speak from experience. 93 percent of students opposed the idea, as did 53 percent of George Harvey students.

At the June 2021 TDSB Planning and Priorities committee meeting in which trustees were set to vote on the merger, students pleaded with Board leadership. “There will be hundreds of students in their last year of high school, myself included, who want to spend it with people they know instead of strangers who will likely be resentful of us for taking their space,” said one student, Sophia Paristeris. “York Memorial students have already been moved twice…We need stability, structure and predictability. We do not need to be moved again…Please, please, please take into consideration everything that’s been said today.”

The TDSB ignored the warnings. Trustees voted in favour of the merger 18-0, citing an expanded course offering and better use of the then-under-capacity George Harvey school building. This September, York Memorial’s 800 students moved into the George Harvey building and the school was renamed York Memorial.

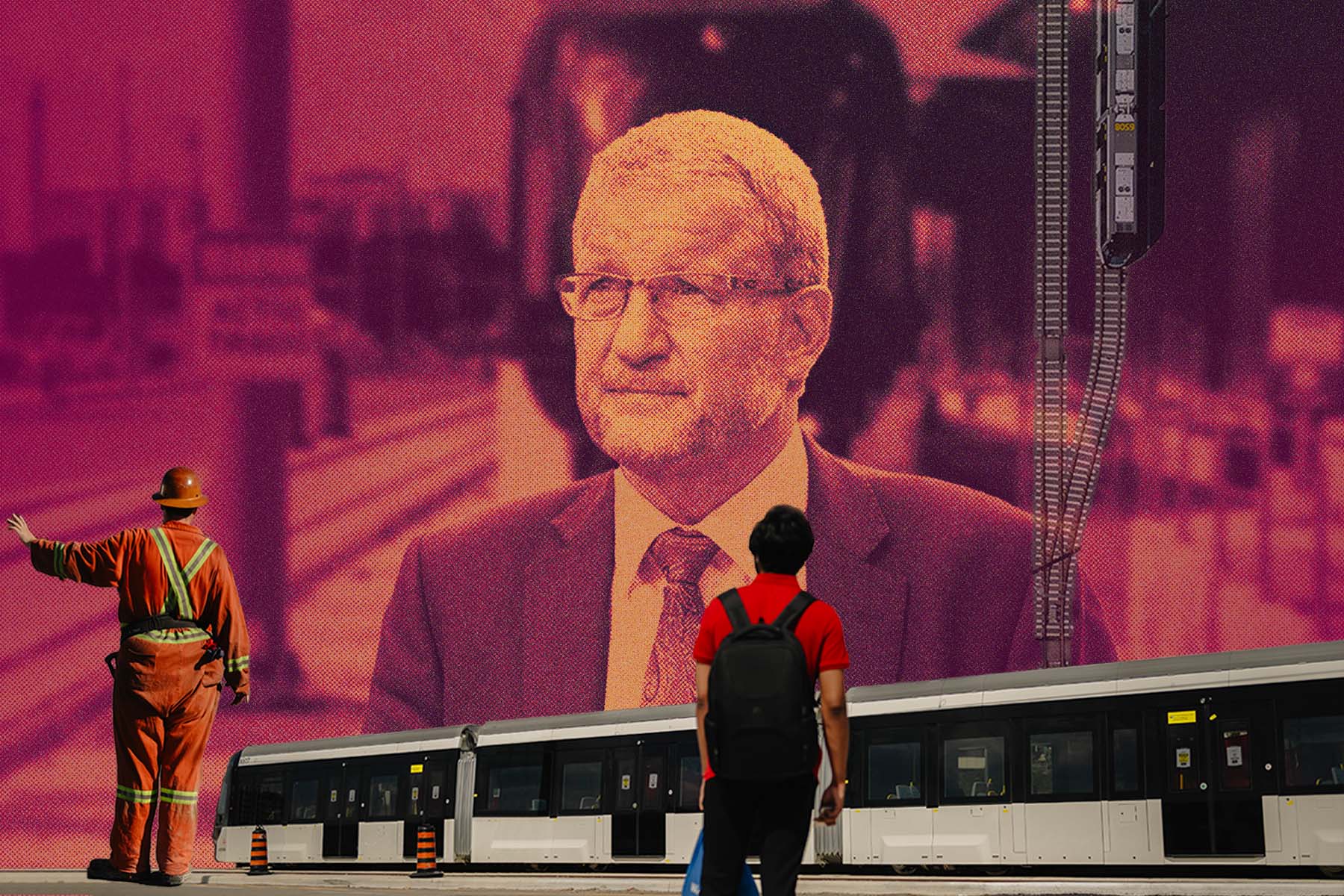

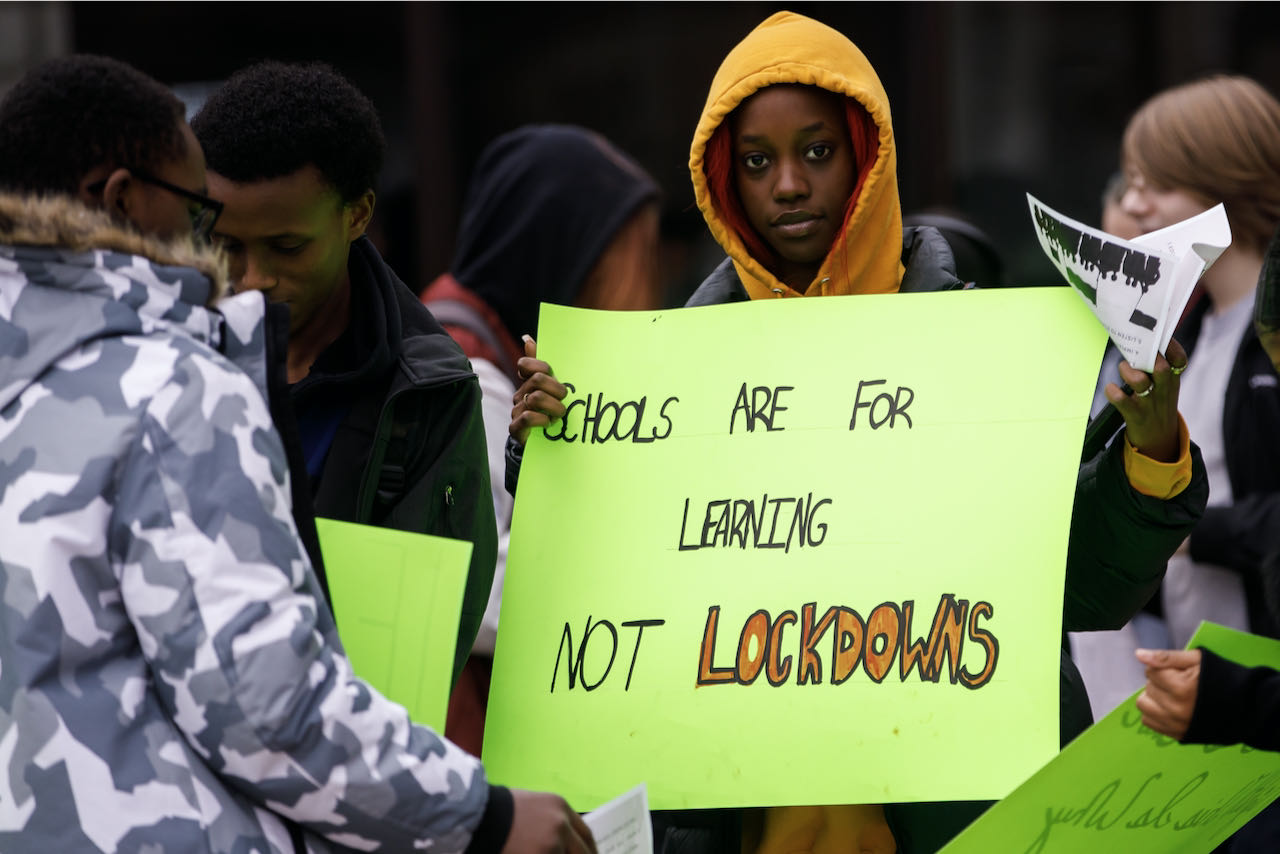

Three months later, everything the students predicted has come true. Since the merger in September, reports have emerged of an unsafe and unsustainable working and learning environment, resulting in a work refusal by some teachers in early November, and a student walkout last week. At the heart of the walkout was students’ keen awareness that a narrative was starting to emerge, attributing the chaos at York Memorial to student behaviour and divorcing it from the environment in which it was taking place.

Reports began with the staff walkout, which took place after a fight involving students and teachers. Teachers reported feeling unsafe, and being threatened by students. All the while, students’ voices were conspicuously absent from the reports. Soon, the stories of student behaviour grew more extreme—and began to resemble the moral panics heard about high-school students for decades—with unnamed teachers telling reporters about “Fight Club-type environments,” drug deals, and filmed sex in the bathrooms.

The most sensational stories are now disputed by both the students and the TDSB.

But the story, both at the institutional level and in the media, has shifted into one about a violent, disruptive student body—which happens to have a significant Black population—terrorizing mostly non-Black teachers, with little attention paid to why students might be angry and lashing out, whether the stories about them were entirely true, what effect this merger was having on their education and well-being, and how the TDSB’s decision led to this point.

Alongside what’s happening in the building, the story at York Memorial is in part about what the public—including education staff and the media—is willing to believe about a student body with a significant population of Black, lower-income students. And in the last few days, it has also become about how people will use those beliefs to justify policing students in their schools.

The more extreme narrative… feels like the product of what a largely non-Black staff assumes of the Black students at the school.

“If they took the time to actually listen to students from day one, this wouldn’t be happening,” says Najma Mohammed, a Grade 11 student who was formerly part of the George Harvey CI student body, and who spoke at last Friday’s student walkout. Mohammed, and the other students and youth workers The Local spoke with, dispute the way the school has been described in the media.

“There are fights in school, but there are no fight clubs,” Mohammed says. “[And] no one’s having sex in the washrooms…You have to keep in mind, this is a school with 14-year-olds, 18-year-olds, 17-year-olds…this is not a television show, [it’s] an actual, real school.”

All of the students and youth support workers The Local spoke with denied the existence of both the fight club and the sex acts, and attributed the discussion of drugs in school to cannabis use. In a statement to The Local, the TDSB said, “While some allegations that have been brought forward have been found to be accurate, others are not as first described. Specifically, staff have no evidence that organized fights or sexual activity have occurred in the bathroom.”

The more extreme narrative, students and youth support workers argue, is in part the result of teachers piecing together bits of rumours or information they hear and see from students. More troublingly, it also feels like the product of what a largely non-Black staff assumes of the Black students at the school.

“[It] reflects the racism that we go through at the school,” Mohammed says. “When we say racism, most of the media dismisses that, because they assume that we’re saying that the teacher is calling me the N-word in class, which is not the case. It’s microaggressions that we face every single day.”

Many of the students who spoke at the walkout described experiencing racism from some teachers: hearing comments from teachers that are ignorant at best and openly racist at worst, being assumed the worst of and deemed violent and threatening, even being told that they’d arranged the walkout just so they could skip class. The TDSB told The Local that “the school leadership team will ensure that there is a clear process that students, families and staff are aware of to report all incidents of racism,” although students and advocates say they’ve already attempted to make reports, with no results.

The issue of the “jump list” illustrates how this narrative has unfolded. Reports from earlier this week mentioned a “jump list” of teachers targeted by students. But students and support workers told The Local that the list was, in fact, of teachers who had been known to say racist things, and about some of whom complaints had been made to teachers and administrators with no apparent consequences. For students, the list is part of a broader whisper network established in the hopes of communicating with and supporting each other in the face of inaction from the administration.

“As Black students, it’s hard to defend ourselves over nothing but simply being Black,” one Grade 12 student told the media during the walkout. “Staff talk to the news and tell them they’re scared of us. Scared!? We are kids! Instead of painting us as monsters, why don’t you ask us why?”

“Has anyone asked why students are fighting, and why students are angry?” Another student said.

The sensational accounts about violence at the school have overshadowed the realities of learning conditions: students have reported not having teachers for some of their classes, and having to learn independently in the cafeteria, library, and hallways; classrooms are under construction and hallways are overcrowded, sometimes with classes that don’t have anywhere to go; the bathrooms don’t have toilet paper, soap, or garbage cans; there’s been a revolving door of school administrators.

“In my third period of class, I haven’t seen my teacher in a month,” says Mohammed. “When you don’t have a teacher, you’re left stranded…For the past month, I’ve maybe had a supply teacher like, three, four times, but the rest of the time I was let out to the cafeteria.”

“If you’re putting us in a trash environment…when we said that we don’t want to be there…and [you] expect us to figure it out ourselves, we’re gonna lash out,” says Josh, a Grade 12 student. He’s using a pseudonym out of fear of the repercussions of publicly criticizing the school’s administration. “And once the administration regards you as a disrespectful student, they feel as if they can do whatever they want with you.”

Fires, Plagues and Also High School

Their school burned down, they survived a pandemic, and endured the ordinary teenage heartbreaks and triumphs under extraordinary conditions.

Vanessa Henry and Cornelious Ajibola work for For Youth Initiative (FYI), an organization supporting Black and other racialized youth that helped organize last week’s walkout. Housed just next door to York Memorial, they’re visited by students during lunch and after school every day, and they’ve seen how the learning environment this year has affected even the most engaged, high-achieving students.

“If you [don’t have] teachers, or if you don’t have the classroom space, if you don’t have the resources, you’ll have students in the hallway, and students skipping,” Henry says. “[And] when these students are exposed to racial violence, there’s nothing done to hold the people who are doing this to them accountable,” she adds. “It’s getting them angry.”

Neither Henry nor Ajibola deny the existence of fights—the two get called into the school once or twice a week, sometimes by staff, sometimes by students, to address disputes between kids. But their frustration is directed at the teachers and the TDSB, for not being able to de-escalate conflicts between the students before they lead to full-blown fights, or address the school conditions that make students angry. “That work isn’t happening because there’s an expectation that these students are just wired like that,” says Henry.

Henry is keenly aware of the fact that the same students fighting in the hallways of the school are getting along just fine when they visit FYI’s offices after school, or during lunch. Their behaviour, she says, is closely tied to their experiences in the school building.

If the administration doesn’t earn back the trust of the students, the students won’t want to listen to anything they’re told, Ajibola points out. “[And] when a fight does eventually happen, the school will ultimately call the police. Then you’re having these kids get arrested, and that’s how the cycle begins of kids coming in and out of jail.”

“York Memorial students have already been moved twice… We need stability, structure and predictability… Please, please, please take into consideration everything that’s been said today.”

This week, the events at York Memorial have resurrected a wider discussion, about the presence of police in schools. Staff and students say police are regularly called to York Memorial, including once following reports that there was a person with a gun in the school (no gun was found when police searched the building). Students and youth advocates say that teachers and administrators are far too quick to call the police for issues that could be solved through de-escalation.

Josh has witnessed police presence in the school before—in his observation, their presence doesn’t de-escalate conflicts between students. “I guess the teachers expect the police to step in, and the police are expecting the teachers to step in. And there’s just zero communication between both parties, from what I can see,” he says. To him, police presence feels more like an intimidation tactic than anything else.

Najma Mohammed reports having similar experiences with the heavy police presence at the school. “I just think it’s really unfortunate, because the demographic at our school is mostly Black students, from the suburbs where, unfortunately, police have not done their job the greatest. I personally live in an area where police are here sometimes and they abuse their right as officers. Seeing them in my neighbourhood, then going to school and seeing them, is obviously very fearful and very traumatic.”

Many of the student speakers at the walkout described police presence as only increasing tensions; the walkout organizers’ demands to the TDSB include no police presence on school grounds unless no other option is available, and better training for teachers to de-escalate conflicts. They’ve also asked the school to release the details of how often police have been called to the school since the beginning of the year, and for what reason, as part of a broader inquest into issues of racism at the school.

But the events at York Memorial have been broadly used as a justification for reopening the discussion around the School Resource Officer (SRO) program, an initiative begun in 2008 that brought police into schools after the shooting death of 15-year-old Jordan Manners at C. W. Jefferys Collegiate Institute. The program went against the recommendations of the report commissioned by the TDSB in the wake of Manners’ death, and only ended in 2017.

Five years later, and with new trustees on the Board, the TDSB’s most recent Planning and Priorities committee meeting felt like history repeating itself: speakers and trustees re-hashed arguments on the merits and harms of having police in the building, despite the years of effort it took from community organizers and education advocates to make clear to the TDSB that any potential benefits to having police in schools were outweighed by the discomfort, fear, and marginalization experienced by Black, Indigenous, and other racialized students.

At the December 5 meeting, a six-hour marathon that saw people on both sides of the issue passionately discussing policing in schools, and the spillover December 7 meeting, the TDSB didn’t indicate any plans to bring back the SRO program. But TDSB executive superintendent Jim Spyropoulos did tell the Board that “if a decision is made related to the temporary presence of police in schools, because whatever circumstances are happening necessitate that, [we would] do that in a very thoughtful way, based on a very specific process which we create and stick to.” The statement struck advocates arguing against police in schools as noteworthy—like a door that had been shut for five years being opened a crack.

It’s emblematic of the priorities of some members of the public, the TDSB, and the media, that an issue which started as being about a lack of adequate access to education following a poorly-thought-out merger by the Board—which is disproportionately affecting low-income Black students and about which students and parents warned the TDSB years in advance—has spun off into a conversation about the violence enacted by the student body, and whether (and how) these Black students should be policed.

In a letter to parents and students after the December 2 walkout, TDSB executive superintendent Uton Robinson said the hiring process was underway for a new permanent principal, vice principals, and teachers. The letter promised new supervision and counselling supports, fully stocked washrooms, and new tutoring and mental health programs, among other changes. The Board told The Local they were also assigning additional safety monitors, including in bathrooms. But the organizers of the walkout have received no indication that their demands for transparency and review from the board will be met.

Everything that’s happened since school began in September “is even worse than a lot of us predicted,” says Josh. In a normal year, he and his classmates would be thinking about graduation and about their future. But all of that feels impossible under current conditions. “A lot of my peers aren’t really motivated to even attempt to figure out what’s happening next year…[we don’t know] how our year’s going to end,” he says.

“It’s not the first time that we’ve been ignored. And because we’re from the communities that we’re from, and the neighbourhoods that we’re from, the city feels like they can just do whatever they want with us. And we’re left to figure it out.”