This investigation is a collaboration between The Local and The Narwhal, a non-profit online publication that tells stories about the natural world in Canada.

The drive west along the 401 into Mississauga is lined with factories, box stores, furniture outlets and timber suppliers. It’s an industrial area, but also a commuters’ hub, where people from across the Greater Toronto Area come to gather at mosques, temples and weddings in splashed-out convention centres.

Residents seem unaware of a facility in an inconspicuous office building at the intersection of Ambassador Drive and Kennedy Road South, one that uses an invisible and odourless carcinogenic gas.

The plant is owned by Sterigenics, which sterilizes medical supplies, like respirators, using ethylene oxide—an effective sterilant of heat-sensitive devices used by many of North America’s doctors, hospitals, and health centres. Ethylene oxide emissions are toxic to humans when high amounts are breathed in and the chemical has been considered to have “a probability of harm at any level of exposure” by Environment Canada and Health Canada since 1999.

Sotera Health, the Ohio-based company that owns Sterigenics, has been named in a series of American lawsuits brought by claimants who say they developed illnesses, particularly cancers including leukemia, myeloma, lymphoma and breast cancer, because of ethylene oxide exposure. In 2023, the company agreed to settle a class-action lawsuit in Illinois, paying claimants US$408 million. It’s also paying out US$35 million in Georgia. In both instances, Sterigenics said the settlements should not be considered an “admission of liability.” A New Mexico case is pending.

But while there has been outrage over the chemical in the U.S., some people in Canada don’t seem to know about it yet. The Toronto-area neighbourhoods where Sterigenics placed its past and current factories—Scarborough and Mississauga—are also home to some of the region’s largest immigrant communities.

From at least 2004 to 2022, Sterigenics had a facility in southwest Scarborough. There, in late 2021, federal government researchers found “detectable plumes” of ethylene oxide, which they called “a human carcinogen,” in a neighbourhood known as the Golden Mile. According to the researchers, the plumes spread as wide as 900 metres and hovered over a church, dense housing, a busy mall and several small businesses and eateries. A public school is about 500 metres away.

Born and raised near the Golden Mile, Krissan Veerasingam had no idea a factory releasing ethylene oxide was so close to home. “There’s a reason why a lot of immigrants came here, because there are so much industry and factory jobs available,” said Veerasingam, a co-founder of the Scarborough Environmental Association.

Veerasingam’s parents immigrated from Sri Lanka and his father once worked in a Scarborough plastics factory. He said it’s important that entry-level jobs exist for newcomers. “But on the other hand, [Scarborough] being a densely populated suburb, heavy regulation is required to make sure that the air we are breathing is not going to impact the wider community and the workers who work there,” Veerasingam said.

“People just like my dad [are] working there…they put a lot of trust in the people employing them.”

In 2022, Sterigenics closed its Scarborough location to relocate to the other side of the region, moving into an almost 28,000 square-foot facility in Mississauga. The company reported ethylene oxide emissions from the new facility to the federal government in 2022, the last year for which data is available. It is unclear why it moved; as of writing, the location is not listed on the company’s online map of its 48 sterilization facilities in 13 countries, including China, Brazil and the U.S., as well as two other Canadian factories, one in Port Coquitlam outside Vancouver and the other in Laval, Que. The map notes various technologies used at each plant, but not ethylene oxide: for months, a note at the top has said, “This page is under construction. Please come back …” for that information.

The Mississauga facility is in a less residential area than Sterigenics’ old Scarborough location. Its closest neighbours are mostly industrial facilities on a major trucking route along Ambassador Drive. But snaking through these factories are clusters of community gathering spots.

American researchers have used a radius of five miles, or about eight kilometres, to measure the population exposed to ethylene oxide from nearby factories. In Mississauga, that encompasses restaurants, community centres, schools and a Kids and Company daycare—the director said they had never heard of the company—as well as the Paramount Fine Foods Centre, an entertainment arena with a capacity of 5,000.

Two mosques also lie in the circle: Sayeda Khadija, a five-minute drive away from Sterigenics, and Jame Masjid four kilometres away. Spokespeople for both said they were unaware of the factory. “We do have small children and families that attend our facility,” Jame Masjid congregation member Kamal Syed said. The mosque sees 2,000 people attend prayers every Friday. “We would definitely be concerned about any toxic emissions.”

On cold days, smoke and steam can be seen billowing into the air from various facilities. Commuters and workers are used to seeing the horizon of industry, not knowing what each manufactures or emits into the air. Just over two kilometres away from Sterigenics lies an expansive golf course, where a representative voiced concern that a company close by could be emitting ethylene oxide, saying, “People are breathing in the air [when] they golf.”

A Sterigenics spokesperson said by email the company could not provide a tour of the Mississauga facility because of a “commitment to confidentiality and security.” The company did not respond to four phone calls or detailed questions sent two times.

To understand the state of ethylene oxide emissions in the Greater Toronto Area, The Narwhal and The Local interviewed dozens of residents and local politicians, as well as representatives from various health networks and several ethylene oxide experts across North America. We also reviewed Canadian and American regulations for the chemical, as well as documents relating to American lawsuits involving Sterigenics operations, speaking with multiple lawyers representing alleged victims of ethylene oxide contamination in the U.S.

We contacted the provincial Environment, Natural Resources and Economic Development ministries, Health Canada and MP Iqwinder Gaheer and MPP Deepak Anand, both in Mississauga. None responded to detailed questions.

We spoke at length with an Environment and Climate Change Canada scientist whose team identified the plumes of ethylene oxide over Scarborough in 2021. We also conducted email interviews with Public Health Ontario and Environment and Climate Change Canada, as well as a number of local politicians.

In 1999, Environment Canada labelled ethylene oxide “toxic,” recommending “additional investigation of the magnitude of exposure of populations…to assist risk management actions.” In 2003, the federal department issued more warnings, including a risk management strategy with the goal of reducing emissions of ethylene oxide to “lowest achievable levels” to minimize health risks and meet standards “comparable to what is currently in place in other jurisdictions, primarily the United States.”

It’s not clear what, if anything, the federal government has done since then to regulate ethylene oxide in the air, or to protect workers and other Canadians who are exposed to it.

Most government departments, politicians, health care providers, and researchers referred us to the provincial Ministry of Environment, Conservation and Parks, which is responsible for monitoring pollution. After 14 emails and five phone calls asking what regulations are in place to protect Ontarians from ethylene oxide and if there are plans to study ethylene oxide contamination further, the ministry only said twice via email that it does “not have any input at this time.”

What is ethylene oxide and what are its links to cancer?

Ethylene oxide has a versatile history. A century ago, it was used as a “powerful insecticide,” then as a hospital room fumigator, according to the Chicago Tribune. Today, medical sterilization is the number one emitter of ethylene oxide in Canada, used by approximately 120 healthcare facilities according to CAREX, which studies Canadians’ exposures to known and suspected carcinogens.

Smaller amounts of ethylene oxide are used as disinfectants, fumigants or insecticides, and in products like antifreeze. It’s also used globally by the spice industry to reduce microbial contamination like E. coli and salmonella. Health Canada removed ethylene oxide from its list of permitted food additives in 2017 but did not respond to questions about exactly what that means.

While the chemical is useful, and in use, its dangerous properties are not news: in 1981, a Shell Oil executive wrote after a conference on industrial carcinogens that “the biggest problem that we have right now is ethylene oxide.”

In its risk management strategy, Environment Canada said cancer is the main impact of ethylene oxide on human health and that the chemical could be harmful at any level of exposure. The U.S. National Toxicology Program has listed ethylene oxide as “known to be a human carcinogen” since 2000, and in 2021 stated that lymphoma and leukemia are the cancers most often associated with exposure. The Canadian Centre for Occupational Health and Safety points to organ toxicity, reproductive toxicity and germ cell mutagenicity as possible effects of exposure, meaning there’s the potential for unborn children to be affected, too. The centre also said long-term chronic exposure to ethylene oxide can harm the nervous system and cause asthma.

Researchers are concerned with emissions, or what is coming out of factories, as well as ambient air, or the air we breathe. There are currently no enforceable federal regulations around ethylene oxide levels for either.

Canada does have reporting requirements: facilities that release certain chemicals, including ethylene oxide, at certain volumes are obligated to report emissions to the National Pollutant Release Inventory. Sterigenics is one of two Ontario companies that does so for ethylene oxide, with its first entry logged in 2004, in Scarborough.

In 2005, Environment Canada also released guidelines to encourage sterilizers to reduce ethylene oxide emissions: they state that owners and operators of facilities that buy or use 10 kg or more of the chemical annually should maintain control of 99 percent of emissions, or ensure the concentration of the chemical released to the atmosphere remains below one part per million. The federal department also said Ontario has its own health-based guidelines regarding ethylene oxide emissions.

But guidelines are not enforceable regulations. And it doesn’t seem like anyone is proactively checking whether they’re being met. Fe de Leon, a researcher and paralegal at the Canadian Environmental Law Association and a member of the National Pollutant Release Inventory working group, said “the only way that we’ve seen that quality control happen at the facility level, is if somebody points out that there’s an error … And unless somebody points it out, it doesn’t get captured.”

“It needs to be scrutinized more,” de Leon added about the inventory.

What Environment Canada researchers testing for ethylene oxide found around a Sterigenics plant in Scarborough

Elisabeth Galarneau, an air quality researcher with Environment and Climate Change Canada, was the lead scientist on a team studying ethylene oxide emissions in late 2021.

Her team partnered with an American company to do the study, attaching equipment to a Ford F-650 truck modified to be a mobile laboratory. Driving around Toronto to monitor ethylene oxide in urban air, the team recorded levels near known emitters like healthcare facilities.

Galarneau said that when her team drove near Sterigenics, ethylene oxide contamination was immediately notable—with “detectable plumes” hovering over the neighbourhood.

“We did this strategy of going back four times…there were times we drove around the facility on days where the winds were [coming] from different directions and the pattern that we saw, of where we saw the ethylene oxide, was exactly consistent with that particular facility being the source, either that facility or something else that is near that facility,” Galarneau said.

Over a period of three days, Galarneau’s study found average ethylene oxide concentrations of 0.43 parts per billion in the air in the vicinity of Scarborough’s now-closed Sterigenics plant. This suggests emissions may have pushed ethylene oxide levels in ambient air above Ontario’s health-based guideline: while her team’s longest study period was just 37 minutes, the guideline recommends no more than 0.11 parts per billion measured over a 24-hour period and 0.022 parts per billion measured on an annual basis.

“The Sterigenics facility was by far the highest concentration that we measured,” Galarneau said. Her study showed there was more ethylene oxide in the air around Sterigenics’ fence than anywhere else she observed in Toronto.

Sterigenics did not respond to detailed questions about emissions reductions measures in Scarborough or Mississauga, its procedures to protect workers, or the potentially harmful effects of ethylene oxide.

On its website, Sterigenics maintains, “No generally accepted science demonstrates that low-level [ethylene oxide] exposure from Sterigenics’ facilities cause medical conditions. [Ethylene oxide] is a naturally occurring substance, unlike many other chemicals at issue in other environmental litigation. [Ethylene oxide] consistently occurs in the environment from natural/everyday human activity, often at levels above those to which the general public is exposed to long-term from the Sterigenics facilities.”

While it is true that ethylene oxide is produced naturally, emissions due to natural sources such as waterlogged soil are “expected to be negligible,” according to an assessment report explaining its designation under the Canadian Environmental Protection Act.

The act lists ethylene oxide as a Schedule 1 chemical, meaning definitely and highly toxic. Yet, according to de Leon, “there’s not a lot of specific regulation” at either the federal or provincial level.

Provinces are responsible for overseeing emissions and monitoring compliance of industries that emit pollutants, although the federal government does set guidelines and make recommendations. Business owners in Ontario that “plan to carry out activities that have the potential to impact the public or natural environment” are required to get an environmental compliance approval, which has a public comment period built into the process. Exemptions are made for businesses with “less complex operations,” which are required to register under the Environmental Activity and Sector Registry.

The City of Mississauga told us Sterigenics does not have a provincial compliance approval. Instead, the company’s past and present locations are listed on the environmental registry. The registry option, de Leon says, is available in order to “reduce the burden on industry who wanted to operate in Ontario” and is designed to “demonstrate that these types of facilities have a lesser harm to the environment in terms of their releases.” A registry listing does not require a public comment period.

In recent years, Sterigenics has reported a decrease in its emissions on the national inventory. In 2019, the company reported 0.88 tonnes of ethylene oxide. In 2020 that number was down to 0.19 tonnes. That year, Sterigenics noted in a comment on its “pollution prevention” activities that it had “Routed exhaust from one emissions source to an emissions control device. This change reduced emissions released to the environment.” De Leon said that doesn’t reassure her fully, especially given the lack of regulations and monitoring.

“If you look at the data that’s associated with ethylene oxide…the levels of impact are still happening at the lowest level. Particularly for workers, the best level is zero. Any level is harmful exposure,” de Leon said.

Last year, the company told the National Observer its new Mississauga location is equipped with a “state-of-the-art emissions control system” that can capture “99.9 per cent of total ethylene oxide emissions.”

Sterigenics has agreed to pay out nearly half a billion dollars to Americans claiming harm because of its operations

In 2019, Sterigenics shut down its plant in Willowbrook, Ill., which is called its most “infamous facility” by lawyers representing clients suing the company. The outrage began after a study by the Illinois Department of Public Health found the number of Hodgkin’s lymphoma cases in women living near the facility between 1995 and 2015 was 90 percent higher than expected.

Concerned citizens formed the group Stop Sterigenics in response to the report, and protests and public outreach led to an order by the Illinois attorney general for Sterigenics to cease operating in February 2019. According to the Chicago Tribune, average levels of ethylene oxide at the Environmental Protection Agency’s 10 monitors plummeted in the six days after the shutdown: they were at least 50 percent lower at all monitors and more than 90 percent lower at the testing locations closest to Sterigenics. By March, Illinois Public Health had published its findings in a definitive final report, and by September, Sterigenics announced it would be discontinuing operations in Willowbrook.

Then came the lawsuits: in Illinois alone, 879 of 882 claimants eligible to participate in a US$408 million settlement program have opted in. That leaves three open cases as of late 2023. In a press release last summer, Sterigenics maintained its Willowbrook operations did not “pose a safety risk to the surrounding community” and said settlements are not to be “construed as an admission of liability.”

The press release continued: “As we have done throughout our history, we will continue to operate all our facilities in compliance with applicable rules and regulations and best industry practices…” Sterigenics did not respond to detailed questions about its operations or legal issues in the U.S.

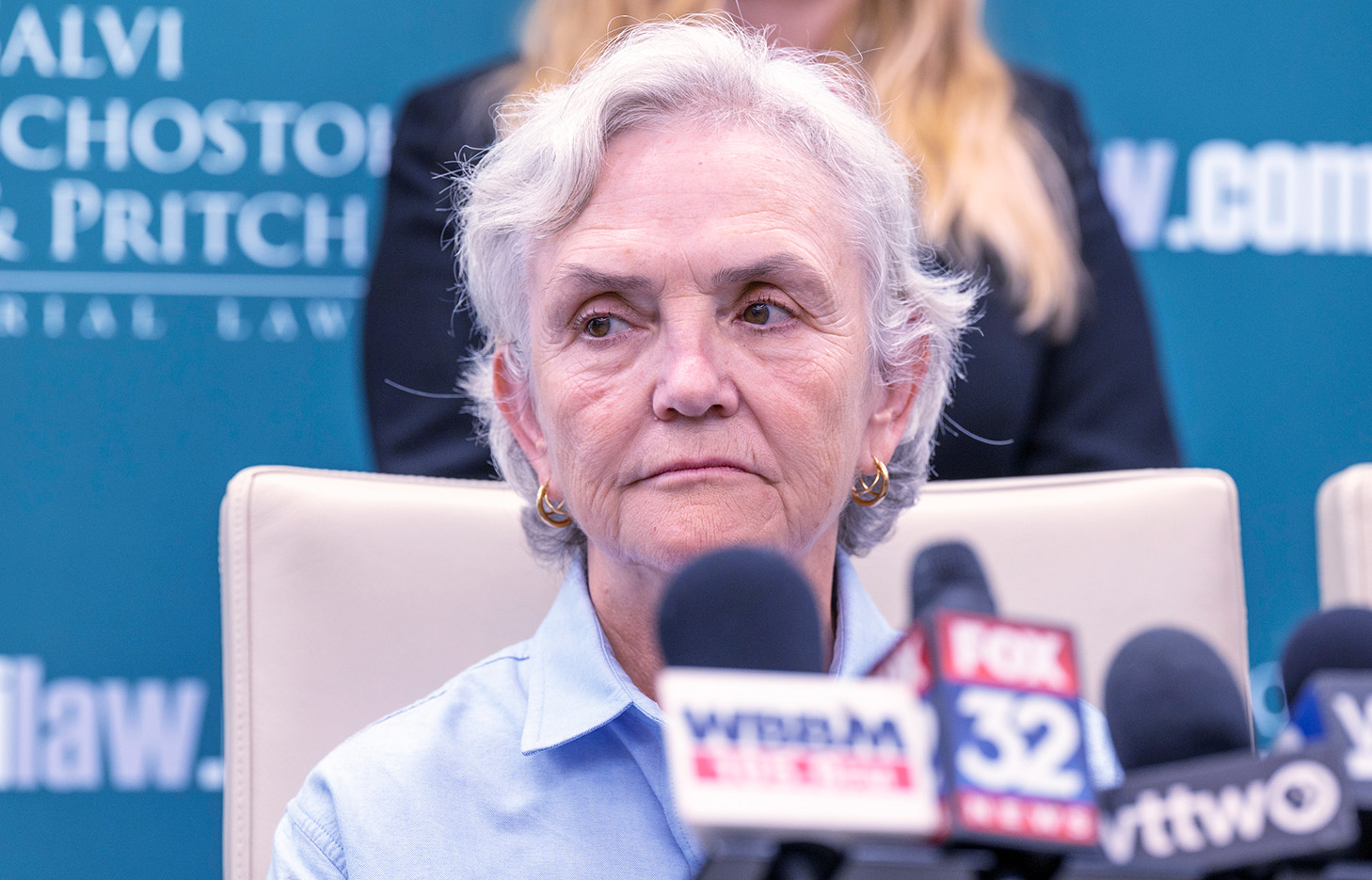

“There was a lot of anger, resentment, and sadness that enveloped the whole community,” microbiologist Urszula Tanouye told us.

A Stop Sterigenics leader, Tanouye grew up in the Willowbrook area. She helped organize demonstrations, including an “empty stroller protest” to symbolize the children the community says it lost to cancer and miscarriages. She said the 9,000-person town of Willowbrook is still in “recovery” from an ordeal that allegedly left hundreds with cancer and many more—including Tanouye’s children—with pervasive respiratory issues they believe are linked to ethylene oxide exposure.

Continuously hearing about other neighbourhoods near Sterigenics facilities, Tanouye said, is like a “bad dream.” Calling herself a “reluctant activist,” she said the advice she offers other communities is, “You’re not crazy.”

“Those reports are real, and the industry is trying to paint a picture because it is in their best interest to downplay the effect the chemical is causing,” she said.

Illinois attorney Antonio Romanucci, the co-lead counsel representing more than 300 plaintiffs, told us generations have been impacted by Sterigenics’ ethylene oxide emissions in Willowbrook.

“I think one of the more egregious findings that we saw is how many children were affected by the effects of ethylene oxide,” Romanucci said. “And that’s because they were emitting ethylene oxide within hundreds of yards [of schools].”

Romanucci and his clients say the impact in Willowbrook was merciless, resulting in life-changing and even terminal illnesses for hundreds of people who lived and worked near the facility.

“Among our plaintiffs we saw countless cases of breast cancer, blood cancers and other health conditions—and behind each of those cases is a person who was scared, suffered through pain and procedures and whose life was never the same again,” Romanucci said.

“Everywhere this chemical is, there’s a cloud of death. There’s a cloud of sickness,” Georgia attorney Michael Geoffroy told us. He’s also representing several plaintiffs who say ethylene oxide from Sterigenics facilities harmed their families. “It has affected entire streets. When we plot the locations of some of the victims and some of the cancer survivors, they often live right next door to each other.”

He added it’s unusual to find clusters of such rare types of cancers, pointing to three mothers, all with children in the same classroom, whom he says got breast cancer at the same time. “We owe it to our children to have a clean environment where you can breathe the air and not worry about getting cancer.”

“Everywhere this chemical is, there’s a cloud of death. There’s a cloud of sickness.”

In October 2023, Sterigenics announced it would pay US$35 million to families who lived around its Georgia facility. In a press release, the company said the “settlement explicitly does not constitute an admission of liability or that emissions from its Atlanta facility have ever posed any type of safety hazard to the surrounding communities.”

The New Mexico attorney general has also filed a lawsuit against the company: while a court dismissed some of its claims last August, claims of public nuisance and negligence still stand, and the state was instructed to amend its complaint.

The Local and The Narwhal reviewed publicly available notes and summaries on the American lawsuits. We asked lawyers in Illinois and Georgia to share documentation about the health conditions of clients that had lived close to Sterigenics facilities. All declined, citing privacy concerns.

In February 2023, the Union of Concerned Scientists mapped 104 facilities that use and release ethylene oxide across the U.S., a project it began in 2018 at the request of the Illinois government. The majority are commercial sterilizers like Sterigenics. The group found seven Sterigenics locations currently operating in the U.S., estimating roughly 14.2 million people live within a five-mile radius of an ethylene oxide-emitting facility in the U.S., many of whom are racialized, low-income individuals.

“The very product used to sterilize critical medical equipment also endangers people who live, work, or attend school near these facilities,” the report reads, explaining that multiple commercial sterilizers are often located in densely populated communities near each other in “sterilizer hotspots.”

The report showed many people were unaware they live near a facility that emits ethylene oxide: “Unlike chemical plants or refineries, commercial sterilizers may look like warehouses or large office buildings and be situated in or near residential areas. Often, they do not have large smokestacks or appear to be sites of major industrial activity.”

In 2020, ABC 7 Chicago reported Sterigenics was accused of funneling US$1.3 billion to investors over three years to avoid paying plaintiffs in the event of a successful lawsuit. At the time, the company told ABC it regularly takes actions to “maintain and enhance…financial strength for the benefit of all stakeholders,” adding that, “Assertions that the companies took actions with respect to capital structure in response to ongoing litigation are false.” It currently has an entire web page dedicated to answering investors’ questions about “environmental exposure litigation.”

The Ontario communities around Sterigenics plants, past and present

In March, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency released long-awaited regulatory guidelines for ethylene oxide emissions. Advocates say there are many gaps in these guidelines, but they are still ahead of what Canada has at the moment. Health Canada promises to release a report on ethylene oxide in the coming year, which experts like Galarneau are waiting for to determine the course of further testing and funding.

Her team’s findings indicate a potentially significant threat to public health may have existed in Scarborough. At one point during the Environment Canada study period, ethylene oxide concentrations in the vicinity of the plant got as high as 18 parts per billion—higher than the maximum concentration observed at the Willowbrook Sterigenics facility, which was 12 parts per billion.

Unlike in Illinois and other American locations, where high local cancer rates put Sterigenics’ operations under scrutiny, geographic cancer data for specific postal codes is essentially impossible for the public to access in Ontario. Local health networks and Cancer Care Ontario were not able to provide this information. A director of data quality at ICES, a non-profit research institute funded in part by the Ontario Ministry of Health that collects provincial health data, said the organization is barred by the provincial Personal Health Information Act from sharing regional cancer data, even anonymized.

Meanwhile, no level of government seems to have informed the public of the Environment Canada report, or of Sterigenics’ presence in Ontario.

In Scarborough, both MPP Doly Begum, who has represented the Scarborough Southwest riding for six years, and newly minted Toronto city councillor Parthi Kandavel said they had not heard of Sterigenics. “I can fairly say that the communities are likely very much unaware of [the factory],” Kandavel said.

Resident Catharine Heddle only learned about the closed Sterigenics plant and Environment Canada’s ethylene oxide study when The Narwhal and The Local told her about both. She said she is “extremely alarmed” for her two children: now ages 18 and 20, they both attended the elementary school closest to the former Scarborough plant’s site.

“I was disappointed to be hearing about it from the news media, rather than from Environment Canada,” she said. “I expected that they would let people know the moment they discovered this danger. And it made me wonder if they would ever have informed us that our children were breathing in this carcinogen.”

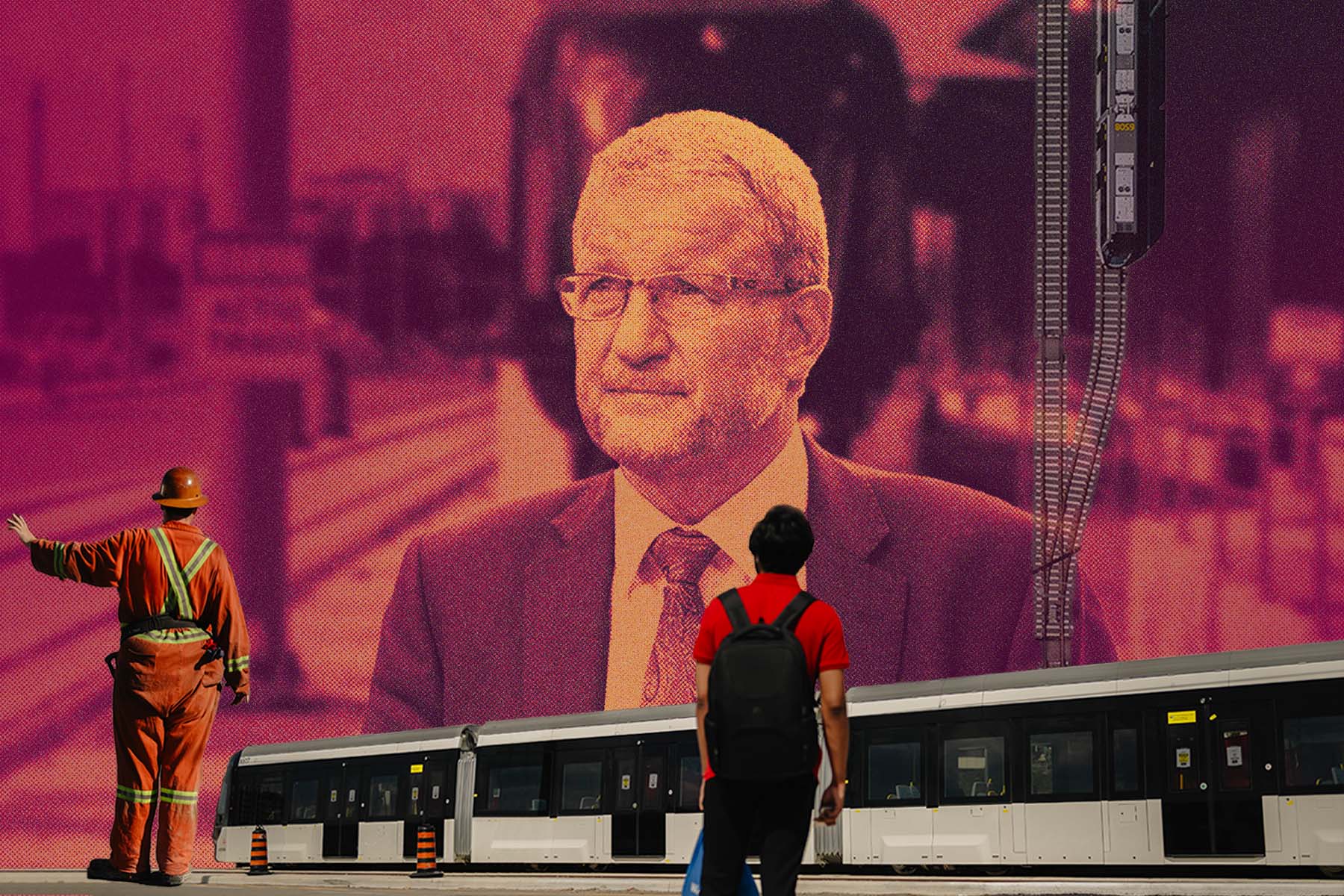

In Mississauga, a media relations person said the city was aware Sterigenics had moved there. The office of Councillor Joe Horneck, who was Mississauga’s acting mayor in February, said via email that Mississauga has “narrow jurisdiction and authority over environmental compliance of manufacturing companies.” Horneck’s office, other city councillors, federal government researchers and Peel Public Health all noted that the provincial Ministry of Environment, Conservation, and Parks is responsible for monitoring air emissions.

Mississauga is vastly different from Willowbrook, a town that is over 75 percent white, with a median income of US$92,202. In contrast, over 60 percent of Mississauga residents identify as “visible minorities,” Statistics Canada’s term for people who are neither white nor Indigenous, and the median household income of the area around Sterigenics’ plant in 2020 was $84,000.

![Kamal Syed said he’s worried about the Sterigenics facility in the vicinity of his mosque. “As soon as [this matter] becomes public knowledge, it's going to create a really big uproar in the community.”](https://thelocal.to/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/TN-JameMasjid-SaugaSN-5-1.jpg)

Darya Minovi, a primary author of the Union of Concerned Scientists report, said she found an interesting “social dimension” in the data, which showed most commercial sterilizers were located in low-income and racialized communities.

She said Willowbrook’s ability to “advocate for themselves and have that facility shut down” was in part because it’s “a predominantly white and more affluent, or not unnecessarily low-income, community,” a sentiment echoed by Stop Sterigenics organizer Tanouye. The environmental researcher believes the use of ethylene oxide in Willowbrook sparked more outrage because of the community’s demographics.

“Our analysis confirmed and found that people of colour especially are disproportionately in close proximity to these facilities,” Minovi said. The only other Ontario company that reported ethylene oxide on the National Pollutant Release Inventory in recent years was also in Mississauga: the waste management operation Clean Harbors. That company said via email that its Mississauga plant is shut and it had “no history of manufacturing or managing ethylene oxide at that site,” although it reported ethylene oxide disposals and transfers from 2020 to 2022.

Long considered a bedroom suburb for workers commuting to Toronto, Mississauga has in recent years been redefining itself as a city, one that continues to grow and evolve in its diversity. The area around Sterigenics’s operating plant is made up of 58 percent immigrants, and it’s no small number of people: in 2021, 78,155 people lived in the municipal ward where the factory is located.

That includes many of the 2,000 people who attend services at Syed’s mosque, Jame Masjid, minutes away from the Sterigenics factory.

“As soon as [this matter] becomes public knowledge, it’s going to create a really big uproar in the community,” Syed said.

Correction—May 3 2024: An earlier version of this article incorrectly stated that Clean Harbors reported ethylene oxide emissions on the National Pollutant Release Inventory. They reported ethylene oxide disposals and transfers.