In March 2023, Justin Cowen’s apartment building was bought by a numbered company—14792670 Canada Inc.

The building at 30 Charles St. East is a three-story yellowstone Edwardian walk-up. Located just off Yonge Street in the centre of Toronto, the 21-unit apartment is one of the few heritage buildings left on the street.

“It’s one of the last affordable buildings around here, and right next to the subway line,” says Cowen, a 27-year-old PhD student who has lived there since March 2022. “It’s really difficult to redevelop, so I thought I was safe here.”

Shortly after the purchase, Cowen says, things began to change at 30 Charles St. “When they took over the lights went out,” says Cowen. That’s not a metaphor; according to tenants, on March 2, 2023 the hallway lights stopped working, and they’ve been out intermittently ever since, sometimes for almost two months.

“They changed the fob system on our front door to high security fobs, which aren’t copyable, and then they refused to give fobs to people whose names weren’t listed on the lease,” Cowen adds. That meant that spouses and roommates ended up locked out at night, tenants say, unable to access the apartments they were paying to live in.

Other residents reported serious problems with repairs and safety. One tenant, Alex Chandler, says he fell down the stairs while the lights were off. He says that tenants’ calls have gone unanswered, contractors began doing noisy construction work outside of working hours, and there were multiple instances of the heat and hot water shutting off.

Gabriella Cook Di Risio started noticing a crack in her ceiling last year. “Then in June it fell through just before my roommate was leaving for work,” she says. She says she contacted the building’s managers multiple times about having her ceiling fixed, but they didn’t respond until they slipped an N13 notice under the door—an eviction notice, often referred to as a “renoviction notice,” which is used to end a tenancy for renovations. When she was given the N13, she was told her renovations would take months.

Bonnie Coole, who has lived in the building for 29 years, was also served an N13. “They have not been into my unit,” she says. “They haven’t done any research to see if any renovations are required.”

“They’re just doing everything they can to get us to leave,” says Coole.

The new owner, 14792670 Canada Inc., was incorporated by Jonas Emre. He’s a lawyer and a former diplomat at the Turkish embassy in Washington, D.C. Emre is also the CEO and co-founder of Harrington Housing, a Toronto-based company with listings in cities from Miami to Los Angeles to London, which describes itself as providing “co-living and student housing” and is “dedicated to transforming the outdated residential leasing sector.”

Harrington’s business model is to subdivide apartments and then rent each room individually. They have a simple online portal, where you can book a room almost like you would a hotel. Harrington goes further and converts the shared space, such as the living room, into another bedroom which they refer to as the “flex room.” That leaves tenants with no shared space other than the kitchen, and often paying more for the unit than they would have if they had secured their own rental.

In an interview with The Local, Emre defended his business model. He stated that management were doing their best to address maintenance issues, and agreed that tenants’ roommates and spouses should receive fobs. He acknowledged the evictions, saying they were justified, and accused tenants of damaging property and illegally subletting.

Harrington Housing is not the only company subdividing rooms and marketing them to students and young professionals. They’re part of a broader group of property management companies, many with links to Harrington CEO Jonas Emre, promising to “disrupt” the rental space. In practice, critics charge, that often means evicting residents, subdividing apartments, and bypassing tenants’ legal protections by attempting to take advantage of legal grey areas.

Shortly after the purchase, rooms at 30 Charles St. East became available to rent through Harrington Housing’s website, and were advertised on the University of Toronto’s student housing portal.

Of the pre-Harrington units, The Local spoke with four tenants who say they have received eviction notices, and another tenant was issued an eviction order after signing an N11, which is an agreement to end a tenancy. That tenant contested the N11 with the Landlord and Tenant Board, saying they were coerced into signing so that they could get fobs for their roommates. The LTB ruled in favour of the landlord, and that tenant was evicted. The rest of the tenants are fighting the evictions.

Since the building was acquired, seven other units have been vacated and then occupied by Harrington Housing tenants.

For the tenants on Charles Street, it was clear what was happening: they were being forced out so that Harrington Housing could subdivide their apartments into more bedrooms and rent those out to students at a higher rate. At the time of writing, a single room in an apartment at 30 Charles St. East was available for rent at $360 per week, equivalent to $1560 per month.

Megan Reynolds, a 22-year-old masters student at the University of Toronto, was one of the students who booked her room at 30 Charles St. East through Harrington Housing. She says she wouldn’t recommend the company.

Reynolds says she was charged a $200 “service fee” when she moved in. Elysha Roper, a staff lawyer at West Toronto Community Services, says she doesn’t believe this fee is permitted under the RTA, which prohibits additional charges from landlords with few exceptions. “A tenant would likely be successful on a tenant application at the LTB,” she says.

Reynolds was initially told she would have two roommates and a common area. Instead she has three roommates. “There is no common area because they converted the only space that we had [to a bedroom],” she says. “So it’s just like a long dark hallway with no lights.”

Another unit in the building has been renovated in such a way that the only way to access one of the bedrooms is through a bathroom.

Reynolds says that when her front door lock broke, Harrington didn’t fix it for over a week. She says there is no radiator in her room, and the heat in the building wasn’t turned on until October 15. She was given an electric space heater, but then the power went out. After asking Harrington to restore it, she says she was told: “don’t use the space heaters because they’re gonna trip the breakers.” Harrington Housing denies having been notified of a broken lock by Reynolds or having instructed her not to use the space heaters.

A tenant who lived at a different Harrington Housing property, who asked not to be named because of worries about her immigration status, says that her apartment was also subdivided. “They didn’t construct any walls, it was just bookcases that made a partition,” she says. “That’s not really a room. There’s no privacy.”

She says she asked Harrington to find her a new room. They did, and gave her two days notice to move. A few months later, she says, they converted the living room in her new place into a bedroom. She no longer rents from Harrington Housing.

In the midst of a housing crisis, however, it’s not difficult to find new students to fill these rooms. A 2021 report estimated that for every bed in student housing there are eleven students that could fill it. The federal government is starting to offer post-secondary institutions cheap loans to build more student housing, but the application process doesn’t start until fall of 2024. In the meantime, students looking for housing often find themselves hunting for a place to live in one of the tightest private rental markets in the country. Vacancy rates in Toronto are just 1.4 percent, and the average asking price for a one-bedroom is over $2,500 a month.

The University of Toronto alone has over 97,000 students, and most of those students need housing. Companies like Harrington Housing have seen an opportunity to provide it while potentially increasing the total rent charged per unit.

In a sponsored article on BlogTO, Harrington Housing brags about their “innovative approach that provides quality rooming options and eliminates the need for long-term commitments, offering a rental solution for students, young professionals and those struggling to find appropriate housing options in the city.”

“The current housing laws are decades old and focus on traditional landlord-tenant relationships,” CEO Jonas Emre told the New York Times. “But co-living is breaking those relationships.”

In Ontario, the Residential Tenancy Act (RTA) governs that relationship, with few exceptions. If you rent a residence and you don’t share a kitchen or bathroom with your landlord, you are probably covered by the RTA and the Landlord and Tenant Board (LTB). There is one standard lease agreement that almost all landlords must use. It grants tenants rights such as protection from eviction, and it prohibits damage deposits and additional charges.

For Emre, and other companies hoping to profit off the overheated student housing market, those protections can be an impediment. Harrington Housing now uses the standard Ontario lease, but they previously used their own rental agreement.

In a blog post he wrote for Pacific Legal, where he is a partner, he focuses on a section of the RTA that exempts properties “intended to be provided to the traveling or vacationing public or occupied for a seasonal or temporary period.”

“The distinction between a hotel and a residential premise is not crystal clear,” he writes. “Similarly, the application of RTA should not be interpreted sharply, in black and white.”

“Emerging accommodation businesses providing a similar short-term accommodation service could well be considered to be exempt from RTA.”

Never miss a story

Join thousands of readers who've signed up for our free newsletter.

"*" indicates required fields

When it comes to Harrington’s business model, Emre says he is simply following the government’s agenda of increasing density.

“There’s a housing crisis, is that true?” he asks. “If you ask me, no, because we are not utilizing houses or apartments or rental inventory in an efficient way. So you have a 1500-square-foot, two-bedroom apartment and two people are staying there. No, why are you not able to utilize and maybe place three people inside, four people inside?”

Emre appears to be connected to a number of other management companies using these tactics to maximize profits on their rental properties. Last year, The Local reported on Urby Housing, a rental management company which uses non-standard rental agreements that critics say tries to sidestep the protections of the Residential Tenancies Act.

Emre is on the articles of incorporation for the similarly-named Urby Enterprises Inc. He is listed on the board of directors, alongside Albert Kevin Harrington, who passed away in February 2023.

When we first contacted Emre for an interview and asked about his relationship to Urby Housing, he said he was “surprised and curious about who are those people.”

Emre acknowledges being the founder of a company called Urby Enterprises, but says that urbyhousing.com, the property management company currently in operation, is a copycat of urbystay.com, a business he previously ran. We couldn’t find a record of urbystay.com to verify this.

“I was the founder and pioneer for this business model,” he says. “We are frustrated that these people are using our business model… even the content on the website.”

“This is completely a copyright infringement and we denounce them doing this,” he adds.

Emre showed us one of the contracts he used with Urby. It was identical to those used by the current iteration of Urby.

There are other almost identical rental agencies operating in the city. One of them is Sky Group Residence, which offers “co-living and student housing in Toronto.” They use the same tenancy contract as Urby and their website offers “flex space” in language similar to that used in Harrington Housing’s FAQ. Sky Group Residence’s articles of incorporation were signed by Timucin Tarik Kursunlugil, whose LinkedIn profile stated he was previously a general manager at Urby Enterprises. Kursunlugil did not respond to a request for an interview, and his LinkedIn profile has since been removed.

Emre maintains he and Harrington are unaffiliated with these companies, and are the victims of copycats.

“You will see big lawsuits,” he says. “We hate them. We’re trying to figure out who are these guys.”

In response to the tenants’ accusations, Emre stands by the evictions, accusing tenants of damaging property. He says tenants have been aggressive, and that maintenance wasn’t being done because staff didn’t want to go to the building.

“There was a young lady working on the management side… and I heard that she resigned because she feels extremely harassed by tenants,” he says.

When asked why tenants might act this way, Emre accused them of being unstable.

“There’s one tenant, he’s sending three complaints to the city everyday,” he says. “I don’t want to blame anyone, but to me it’s not stable. It’s instability”.

Emre also claims that tenants have been illegally subletting.

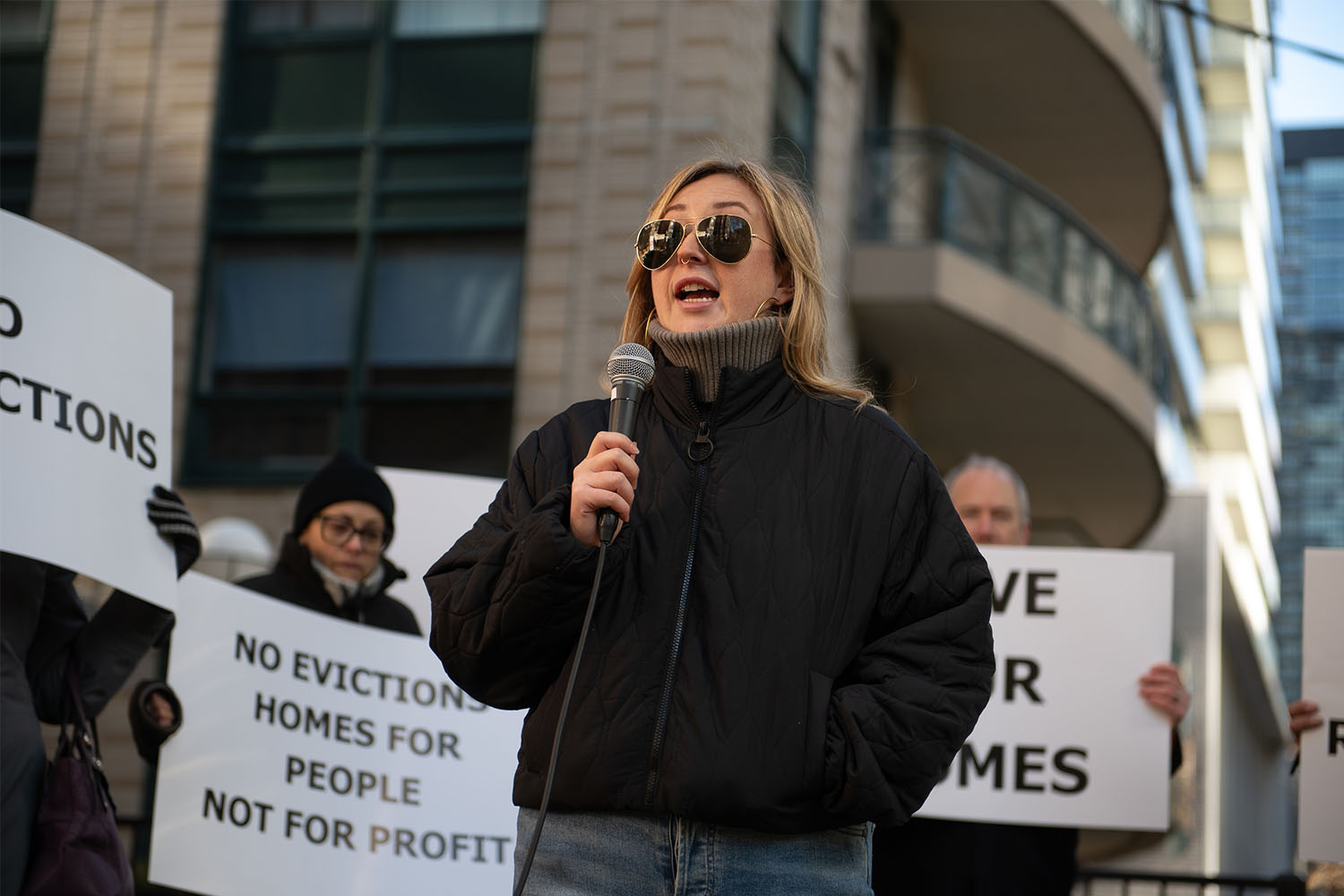

On a freezing Sunday in November, tenants of 30 Charles St. E protested outside their building. Justin Cowen led the chants.

“What do we want? An emergency contact!”

“What do we want? Fobs!”

Jessica Bell MPP, the Ontario NDP housing critic, addressed the crowd. “You all are taking real action to protect your homes from a corporate landlord that is breaking the law in order to make money off you and off future tenants, and I don’t think that’s okay.”

Speaking to The Local, Bell said tenants are “in a really hard spot because the laws in Ontario are not enforced.”

“Harrington Housing is taking advantage of the short-term rental grey area loophole that exists in the city and the province. What we’re seeing with Harrington is they’re kicking out these tenants and they’re moving in people who pay crazy amounts just to rent one bedroom on a weekly basis. That should be illegal, but… Harrington Housing is getting away with it.” Harrington Housing denies that it breaks the law or that any of the tenants at 30 Charles St. East have a lease with a term less than one year.

In the meantime, Justin Cowen and the other residents of 30 Charles St. East continue to face difficult living conditions under the new ownership. The building’s heat and hot water shut off on December 19, Cowen says, and remained off over the winter holidays.

The gas was shut off by Enbridge due to serious safety concerns with the building’s boilers. A property standards order was issued by a bylaw officer, and the heat and hot water was eventually restored on January 11.

A representative for Harrington Housing said the tenants had been given space heaters, like the one Megan Reynolds says she was given earlier in the year that tripped the breakers, and offered alternative accommodation in Etobicoke.

_______

Updated—March 7, 2024: An earlier version of this article included Jonas Emre’s previous name. It has been removed for privacy concerns.

Corrections—May, 2024: A previous version of this story contained a number of errors. It incorrectly stated that “Urby Housing was also founded by Emre.” That has been changed to clarify that Jonas Emre is on the articles of incorporation of the similarly-named “Urby Enterprises.” A sentence that previously stated that tenants claimed that hallway lights were out intermittently for “up to two months” has been changed to “almost two months.” A quote from Jonas Emre previously read: “Why are you not able to maybe place three more people inside?” That has been corrected to say: “Why are you not able to utilize and maybe place three people inside, four people inside?” A photo caption for this story described the apartment at 30 Charles St. East as a “Harrington Housing” complex. In fact, the apartment is owned by a company incorporated by Jonas Emre, the CEO of Harrington Housing, but not Harrington Housing itself. The reference to Harrington Housing has been removed. A previous version of this article included a quote from Jonas Emre that read: “None of the official tenants were living in the place in the units… None. Zero.” That quote was not in the appropriate context and has been removed. A previous version of this article stated that “Emre doesn’t believe the RTA should apply to Harrington’s style of rental.” That statement has been removed as it does not fully represent Jonas Emre’s position.

Clarifications—May, 2024: This story now also includes additional responses from Emre regarding specific allegations from tenants in three different places: “He stated that management were doing their best to address maintenance issues, and agreed that tenants’ roommates and spouses should receive fobs”; “Harrington Housing denies that it breaks the law or that any of the tenants at 30 Charles St. East have a lease with a term less than one year”; “Harrington Housing denies having been notified of a broken lock by Reynolds or having instructed her not to use the space heaters.”