When Hamza graduated college and began searching for apartments on Facebook last spring, a series of listings immediately caught his eye.

“I saw a couple ads that appeared to be by the same organization,” he says. “Very good locations scattered around the province.”

The former international student graduated from Sheridan College in April. He is using a pseudonym because he’s still looking for a place to live and doesn’t want to be viewed as a “problem tenant” by potential landlords.

Hamza went to visit one, a townhouse in Waterloo. The people who showed him the building told him they were a property management company that looked after homes for landlords, renovating them and managing the tenancies. “The place was nice and clean, brand new, nobody lived there yet,” he remembers. Two rooms were already rented out, but there were three or four other rooms still available. It was a good place, well located, and within his budget.

He agreed to move in. But when he got the “lease,” he was taken aback. “I just graduated from college. I was just still a student so I was not experienced with this whole thing,” says Hamza. But something didn’t feel right. “It just was not a standard rental lease.”

In two separate places the one-year agreement stated that “no relationship of landlord and tenant is intended to be created,” instead referring to the agreement as a “license to occupy.” Hamza would apparently be a licensee, signing a contract with a licensor.

The document didn’t even guarantee Hamza could stay in that apartment, stating: “This licence does not confer or be construed to confer any security of tenure to Licensee.” He could, apparently, be moved to another apartment without being consulted, and with just seven days notice.

The agreement also had a $100 charge for overnight guests, a security deposit, a ban on pets, and other conditions and charges which are not legally valid in Ontario.

This agreement was provided by Urby Housing, a Toronto-based property management company that promises “ready to move in luxury co-living spaces.” The document is a non-standard tenancy contract that experts say does not comply with the Residential Tenancies Act, 2006 (the RTA). Instead of a lease, tenants are asked to sign a document that says no tenant/landlord relationship exists and they are instead a licensee being given temporary use of the property.

Urby Housing manages a network of properties. We’ve seen evidence of at least 10, but the Facebook profile which posts these rooms is consistently updating their ads with more rooms. They are not affiliated in any way with Urby, an American company offering luxury rentals in six locations in the US.

Middlemen like Urby Housing aren’t a new phenomenon. But in an environment where the rental vacancy rate is the lowest it’s been in over twenty years, there are many desperate renters—people who might be convinced to abandon their rights to secure a place to live.

Local Journalism Matters.

We're able to produce impactful, award-winning journalism thanks to the generous support of readers. By supporting The Local, you're contributing to a new kind of journalism—in-depth, non-profit, from corners of Toronto too often overlooked.

SupportIn Ontario, tenancy laws are rigid with few exceptions. If you rent a residence and you don’t share a kitchen or bathroom with your landlord, you are probably covered by the RTA and the Landlord and Tenant Board (LTB).

There is one standard lease agreement that almost all landlords must use. It grants tenants rights such as protection from eviction, and it prohibits damage deposits and additional charges. Residential buildings first occupied before November 15, 2018, are subject to rent control.

A landlord, or their agent, can’t do things like retain the right to enter the residence at will. But that’s in Urby Housing’s contract, along with things like: “After 10 days [of the resident’s absence], Licensor has [the] right to advertise the room for potential clients and take necessary measures for that purpose, if the Resident is unreachable.”

“It’s certainly not a valid lease,” says Ryan Hardy, a staff lawyer at the Advocacy Centre for Tenants Ontario. “You can’t get people to contract out of their rights under the Residential Tenancies Act.”

Hardy says he’s both shocked and not shocked by what Urby Housing is asking renters to sign.

“Shocked maybe at the chutzpah, the effrontery of it,” he says “And why am I not shocked? Well, because there’s a profound housing crisis. That is pushing people to even consider these types of housing options.”

According to Rentals.ca the average asking rent in Toronto for a one bedroom apartment is now over $2,500 per month.

“If you had a functioning housing market and somebody said ‘Do you want to pay almost $2,000 to rent part of a living room in a condo?’ you’d tell them where to get off,” says Hardy.

Elysha Roeper, a staff lawyer with West Toronto Community Legal Services, says she sees a lot of cases like this, where landlords are hoping tenants don’t know their rights.

“These aren’t hard cases to win if the facts are in order,” she says. “It’s just a landlord trying to create something very complicated out of a system that is quite rigid and specific, and so I don’t know why they keep trying.”

A closer look at Urby Housing’s agreement shows that they have tried to define these rentals as “short-term,” which may be an attempt to occupy the grey area created by an exemption in the RTA for accommodation that “is intended to be provided to the travelling or vacationing public or occupied for a seasonal or temporary period,” while still guaranteeing long-term rental income.

Roeper doesn’t believe that exemption applies to this case.

“If this were ever to go to a hearing they’re directed under section 202 of the Residential Tenants Act to look at the real substance of the transaction, and so if they’re saying seasonal but they’re offering it for a year, that’s definitely not seasonal.”

“I do feel like the greed is getting worse. People are trying things that you would not have expected in previous years. And it’s spreading.”

After chatting to Hamza, I decided to view a room for myself. I visited the Facebook Marketplace profile he sent us and found that one person was advertising several rooms, all looking newly renovated, with similar furniture. In Toronto they were priced between $1,600 and $2,000 per month.

After contacting the poster we switched to WhatsApp and eventually organized a viewing of a three-bedroom condo unit.

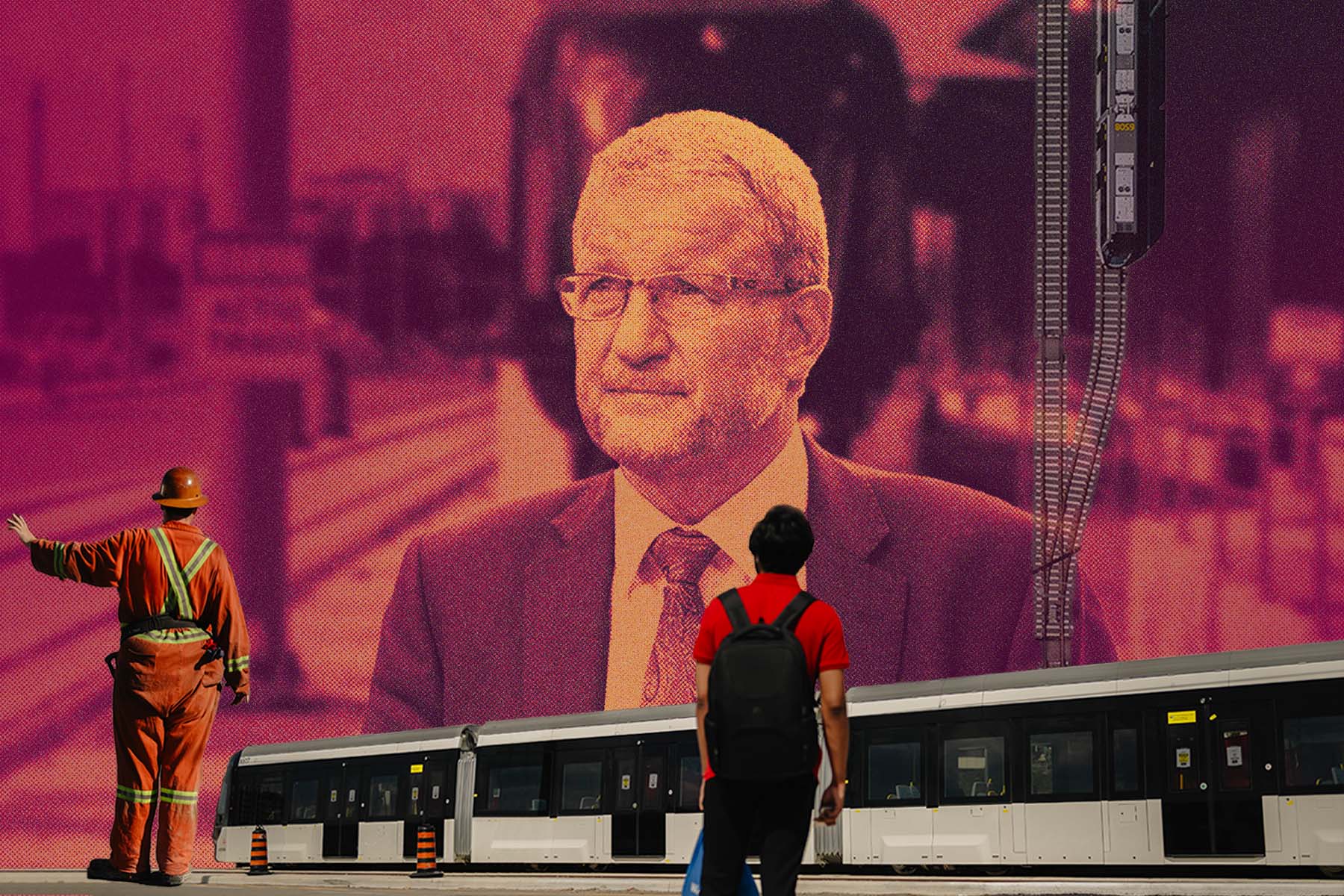

That evening I was met outside the front of a glittering condo tower near Fort York by a casually dressed young woman, perhaps 30. As we rode the elevator together she told me about all the amenities the building had—gym, pool, BBQ, party room—before showing me into the unit.

Tools were scattered around the apartment, and a partly built plywood wall divided the windowed portion of the living area from the kitchen and dining portion. The divided section, the representative told me, would be a fourth bedroom—cutting off all natural light from the living room area, and turning the balcony into part of the “fourth bedroom.”

The three complete bedrooms themselves were already furnished with beds, televisions, a small desk and a nightstand—all using similar furniture to those shown in the ads.

“We are managing this property on behalf of the owner,” the representative told me, “We are not the owner…It’s like a management company.”

I asked how tenants could contact the landlord.

“Always talk to us,” she said. “Maintenance, these kinds of issues, we always take care of this. You will always be contacting us about everything.”

The price advertised for the master bedroom was $1,820 per month, but the actual rate, the representative said, was $455 per week. That seemingly minor difference adds up to paying an additional $1,820 per year, a whole additional month of rent.

I asked if the unit was rent controlled.

“No, it’s a new apartment,” she said.

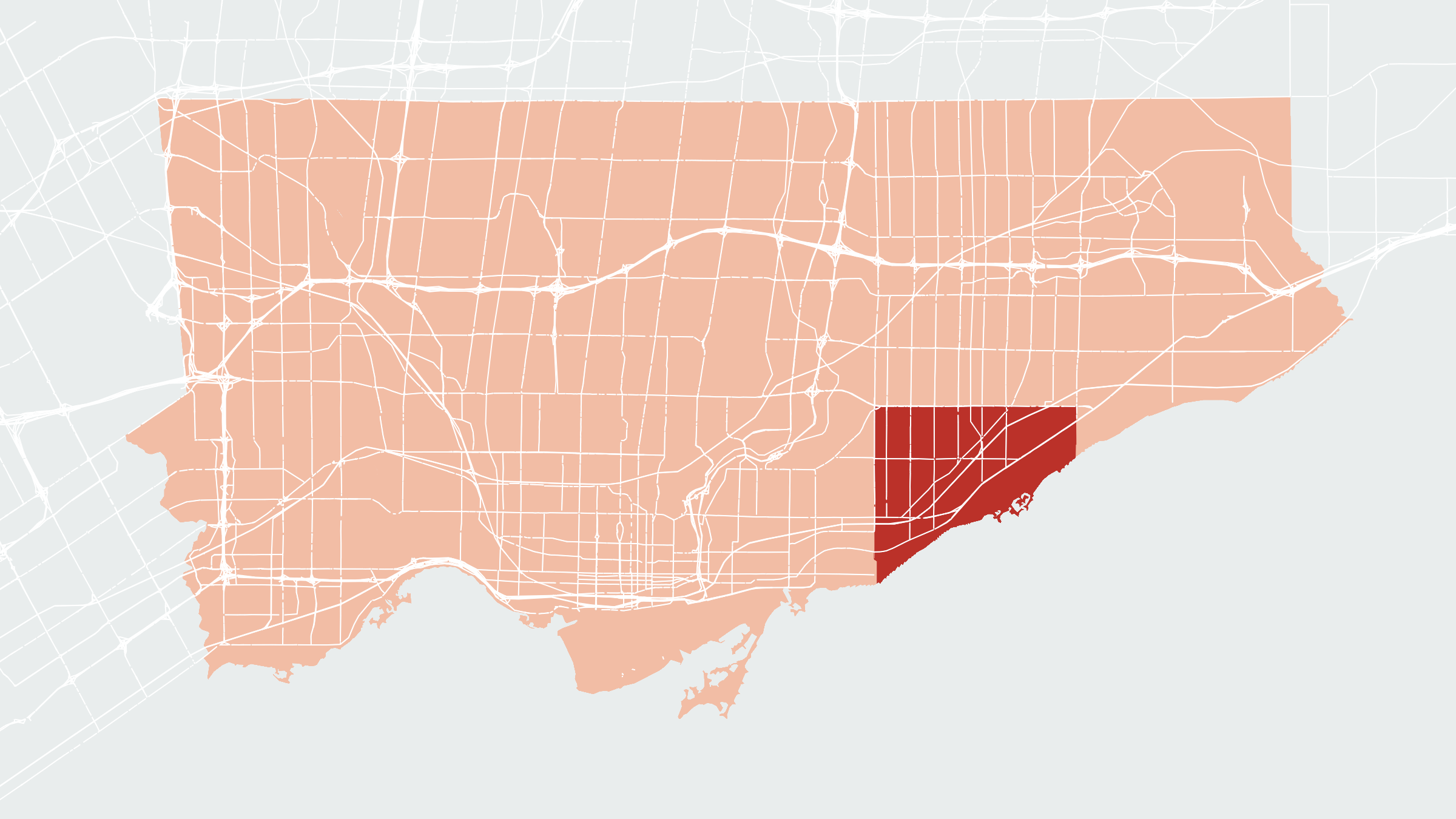

That’s not true. Despite being a relatively new, modern looking condo tower, this building was first occupied prior to November 2018. When I called the building’s management, they confirmed that yes, every unit in that building is subject to rent control.

The next day Urby Housing sent me the same agreement that Hamza had been sent, tailored for the master bedroom of that unit. They did not respond to a later interview request asking them about their contracts.

Urby Housing is not the only company looking for ways around the RTA in Toronto. I’ve heard from tenants in similar situations under other landlords. MPP and Ontario NDP Housing Critic Jessica Bell has posted about Harrington Housing forcing out long-term tenants with tactics like refusing maintenance and not giving roommates and spouses keys to their building at 30 Charles Street, all while they brag about their “flexible” co-living arrangements in paid posts on BlogTO.

For people like Hamza, companies like Urby Housing make the search for an apartment even more difficult. In a properly functioning housing market, tenants wouldn’t have to navigate A1 forms and LTB hearings just to have their rights respected. Landlords wouldn’t be incentivized to force standard rentals into legal grey areas, and seasonal accommodation could co-exist peacefully with long-term tenants.

Hardy says this all leads to pressure on the people who, by definition, own the least: tenants.

“I do feel like the greed is getting worse,” he says. “People are trying things that you would not have expected in previous years, and it’s spreading. Things that used to be Toronto problems are now becoming North Bay problems and Oshawa problems… the desire to just find a hack against even obeying the minimal legal protections we have.”

Hardy suggests some solutions, such as bringing back rent control for all tenancies and increasing the penalties for landlords who break the rules. But he says that any lawyer who works in this area long enough recognizes that the fundamental problem is supply and demand.

“You can work as hard as you can and try to win results for individual tenants, but the real solution is basically just to build more housing and specifically, I would say, more affordable housing,” he says. “Otherwise two other people are going to be having this same version of this conversation ad nauseam.”