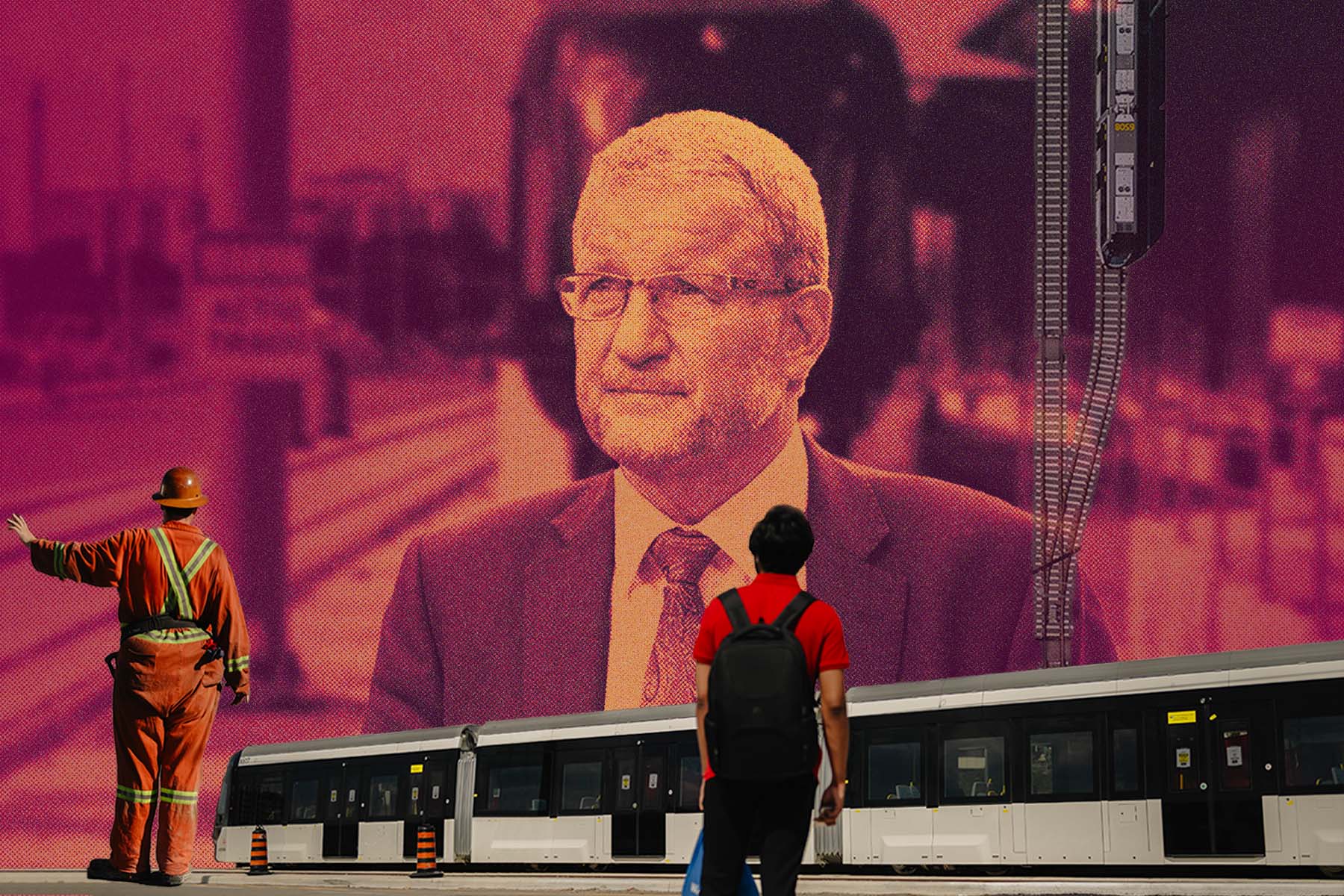

If you had to mark it, the low point of the Phil Verster era as President and CEO of Metrolinx, at least thus far, came during a press conference last September on the fate of the Eglinton Crosstown.

The nearly $13-billion LRT line has been under construction since 2011 and was initially set to open in 2020. In September, after years of delay, and after months of promising an announcement about an opening date, Verster took to the podium to finally provide some answers.

“I have to tell you that I had every intention to predict an opening date, or series or range of opening dates, for the Eglinton Crosstown with you today,” Verster said, light stubble on his cheek, his eyes glancing up from his prepared statement to range around the room. “But I’ve decided against doing so.”

They were simply discovering too many issues each day. And so, the much delayed announcement was Verster steadfastly refusing to announce even the vaguest approximation of when the project would be complete. As the media pressed him for more details, any details, the Metrolinx boss admonished them for their impatience. “I can just say to you … give us some space,” he said.

It was an astounding, bewildering performance. The Eglinton Crosstown is Metrolinx’s first LRT—proof of concept for multiple projects in the works. The decision not to share the agency’s best approximation of an opening date may have been in Metrolinx’s best interest. It may have been in the best interests of the provincial government. But it certainly wasn’t in the interest of the public.

More than that, for transit infrastructure experts, the fact that Verster was only then announcing a plan to deal with the outstanding issues was shocking. “I was surprised by the Eglinton Crosstown conference, by just how far behind things still were,” says Shoshanna Saxe, associate professor in the University of Toronto’s department of civil and mineral engineering. “I was really surprised that there wasn’t yet a plan.”

Days after the press conference, the public learned that Verster’s contract had been renewed for three more years. Metrolinx has refused to release the details of his latest contract, but from a base salary of $506,280 in 2018, Verster’s pay has risen sharply, reaching $856,552 in 2022—the fourth-highest public sector salary in the province, behind only three Ontario Power Generation executives. For context, Janno Lieber, head of New York’s Metropolitan Transportation Authority, the largest transit authority in North America, earned just over $400,000 USD (roughly $540,000 Canadian) in 2023.

That sequence of events—the leader of a provincial agency refusing to answer the most basic questions about a floundering project, then being richly rewarded for it—led to renewed scrutiny on the Metrolinx boss, with critics in the press and at Queen’s Park calling for his firing.

“I don’t know of any other public official in Ontario who’s had their pay increased… while presiding over what can only be described as incompetence,” says Joel Harden, the NDP’s transit critic. “I’m not sure if Mr. Verster is a svengali or if he’s just a charming fellow, and I’m sure he’s an intelligent person in his own right, but I honestly don’t know how somebody can be this richly compensated for such poor performance.”

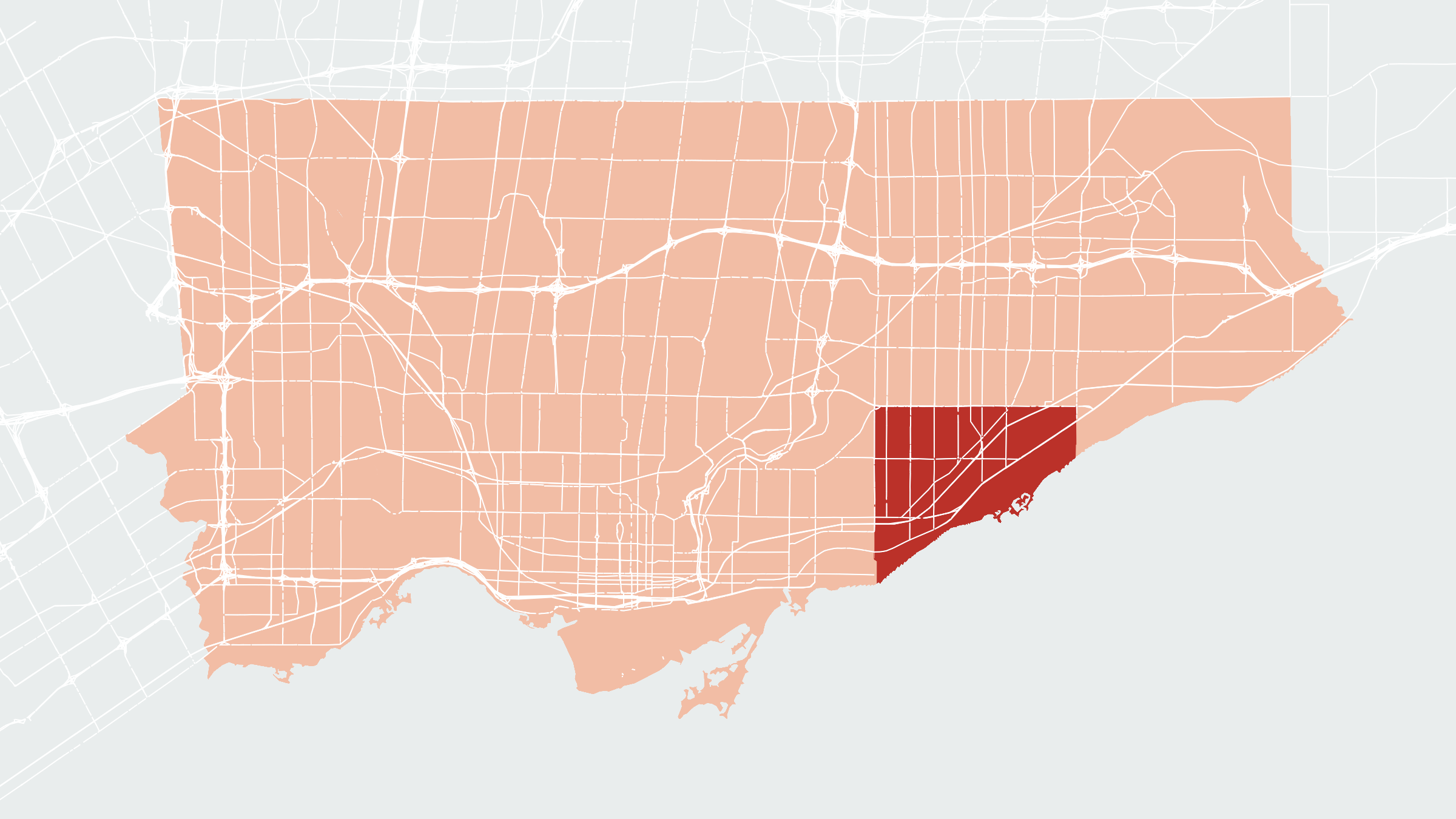

As the head of Metrolinx, the provincial crown corporation in charge of delivering major transit projects across the GTHA, Verster is in the midst of transforming this city—from the long-promised Eglinton Crosstown to the Yonge North Subway Extension to the Scarborough Subway to the Ontario Line, all of which promise to tear up much of Toronto for the next generation. There’s no public servant whose decisions so directly affect the daily lives of so many Torontonians.

But while Metrolinx has become the premiere crown corporation for long-term construction, adept at digging holes and sending press releases, thus far they don’t have a single completed project to show for it. And so it’s no surprise that public anger over its cost overruns, seemingly endless delays, and lack of accountability has landed squarely on the nearly million-dollar bureaucrat in charge. Because regardless of how long Verster stays at Metrolinx, we’re going to have to live with the consequences of his decisions—both good and bad—for decades to come.

Kevin Lindsay still remembers the first time he met Phil Verster. As the Scottish organizer for the UK’s train driver’s union, Lindsay has worked and sometimes clashed with a long series of managers during his decades at the railway. In 2015, Verster was simply the latest—a South African engineer who had spent the last three years with Britain’s Network Rail and was now joining as the managing director of ScotRail, the national rail service of Scotland. And while Verster would ultimately only be in the job for less than two years, Lindsay remembers more about his short tenure than that of any other boss.

In their first meeting, during negotiations with the union, Lindsay says Verster entered with a memorable mix of “this naivety with this aggression.” Tall and broad-shouldered, with a rugby player’s mien, Verster can cut an imposing figure. And to Lindsay, it was clear that Verster wasn’t interested in a cordial working relationship. “He had to be the alpha male in the room,” says Lindsay. Throughout the meeting, Verster scrawled notes. At one point the union man peered across the table—“as if I can’t read upside down, I’ve been going to negotiations for 30-odd years.” On a piece of paper, he says, Verster had written a note: “These bastards don’t like me.”

“From the start to the finish, he came over as a big bully,” says Mick Hogg, an organizer with the National Union of Rail, Maritime and Transport Workers who was also in negotiations with Verster during his time in Scotland. “He attempted to actually intimidate you.” His style wasn’t to consult or collaborate, says Hogg. “It was a simple case of Verster’s way or the highway.”

Verster’s time in Scotland would be short-lived. Under his leadership, ScotRail’s punctuality rating fell to 90 percent, below the 91.3 percent mandated in its contract. A 2016 National Rail Passenger Survey found a “significant decline” in customer service. According to one analysis, ScotRail said “sorry” to riders on social media over 10,000 times in 2016, an average of 30 times a day.

In the press, Verster’s response to criticism was a kind of prickly defensiveness that, years later, would become familiar to Torontonians. “Operating a busy and complicated network is challenging at the best of times—and we are doing so during one of the largest investments in modernisation since Scotland’s railway was built in Victorian times,” he told the BBC.

In Scotland, that kind of explanation didn’t seem to appease anyone. A steady drumbeat of articles hammered away at him, week after week. Why was the leader of the railroad being rewarded so handsomely as commuters suffered? There was outrage about his £265,000-a-year salary (roughly $460,000 in Canadian dollars today), about the £17,000 he received to pay rent on an apartment “in one of Edinburgh’s most desirable areas,” about his private health care and car allowance.

The final straw seemed to come when Verster and then-transport minister Humza Yousaf couldn’t get on the same page about a proposal to compensate riders for poor performance. Yousaf had publicly promised regular commuters a large rebate to make up for the rail service’s year of delays and cancellations. Verster, meanwhile, wouldn’t commit, saying the money in the fund Yousaf proposed using had already been earmarked for other projects. Days later, Verster resigned, leaving the job after less than two years. Perhaps the most common adjective attached to the railway boss in the press on his departure was “beleaguered.”

From Lindsay’s vantage point, it felt as if Verster had strode into the insular, politicized world of Scottish railways and tried to plow his way through a system he didn’t understand with sheer, old-school force. “I don’t think he came from South Africa—I think he came from the 1970s,” he says. “It was like something from another era.”

“I was delighted when he left,” says Hogg. “I was delighted to see the back of Verster.”

Verster moved to a smaller role at East West Rail, where he was charged with delivering a rail line between Oxford and Cambridge. Just six months later, however, he had moved on again—this time to Toronto, as the new president and CEO of Metrolinx.

Never miss a story

Join thousands of readers who've signed up for our free newsletter.

Today, more than six years into this time at Metrolinx, “beleaguered” is not a bad description of Phil Verster’s standing. But the bad headlines and calls for his ouster are a long way from where Verster began his time in Toronto.

When his hiring was announced in 2017, it was near-universally praised. If his time in Scotland had ended badly, an ocean away, Verster was greeted as a potential saviour.

Metrolinx had been formed in 2006 as an “arms-length” transit planning agency, but in reality there had never been anything particularly arms-length about it. “It became very obvious very quickly that it was deeply, deeply embedded in the political environment,” says Brendon Hemily, a public transportation consultant. “It had no independence at all.”

Former heads hadn’t come from the world of transit—they’d been political appointees. With Verster, at last, you had an outsider with genuine railway experience. And rather than hiring from the States, Metrolinx had brought in someone from the U.K., a country with a rail network that may not have been highly regarded by European standards, but was still miles ahead of what was happening in North America.

Verster brought big changes to an agency that had begun as a rather bureaucratic transit-planning organization. “When Phil came in, I think he really brought a very corporate commercial business sensibility to the place,” says one former senior Metrolinx employee. “The changes were quite stark.”

Verster introduced the sponsorship program, in which a single Metrolinx manager oversees a long-term project throughout its lifetime, from planning through construction. He brought over employees from the U.K. with significant railway experience. He talked about technical changes like “level boarding” at GO stations in ways that made transit wonks salivate.

And if Verster had struggled to navigate the choppy political waters in Scotland, in his early days at Metrolinx, he proved an adept operator. Verster had been a Liberal appointee, and when Conservative Doug Ford came to power in 2018, there was reason to think the transit plans of the previous regime, and Metrolinx itself, could be in jeopardy. In a mandate letter to then-minister of transportation John Yakabuski, obtained by Global News, Ford directed the minister to “fundamentally review the function and structure of Metrolinx and determine if any institutional changes are needed.”

Instead, Verster was able to make himself and his agency useful partners in Ford’s transit ambitions. “Verster managed to take the organization from what was very much in the trigger eyesight of Ford and company and turn it basically into Doug Ford’s Rapid Transit Company by producing the Ford transit plan,” says transit watcher Steve Munro.

To some transit observers, that meant Verster became adept at justifying Ford’s desires, regardless of the evidence. “One of the terms that you always heard a lot was ‘making evidence-based decisions,’” says Steve Wickens, a transportation researcher. “And what Metrolinx ended up becoming was an agency that produced decision-based evidence.”

“The role of [Metrolinx CEO] was always to take the flack for any political decision that was controversial,” says Hemily. “And Verster just fits into that mould. That’s why he’s been paid the big bucks, because he’s there to shield the politicians who actually make the decisions.”

“It was a simple case of Verster’s way or the highway.”

Verster’s reputation as a bruising manager in Scotland has followed him here. A common description of his management style is “a bulldozer.” One former senior employee described his style as “command and control.” And in the Verster era, Metrolinx seems to have taken on the characteristics of its leader—an imperious my-way-or-the-highway ethos turned into an agency-wide policy.

“That seems to be his style, and it’s become a Metrolinx corporate style,” says Munro. “I look at Metrolinx as an organization that could have been doing a lot more good in terms of … actively collaborating rather than riding roughshod over everybody. And that has to do in part with the person at the top.”

Like the Scottish union men, community groups in Toronto have found that Verster and his organization are not keen on collaboration. When I interviewed Verster a few years ago about the Ontario Line—a massive construction project that had inspired backlash from communities up and down its route who said they had not been adequately consulted—he was firm about the limits of what Metrolinx was willing to discuss, and what they would dictate. “What we do on our projects is we work out technically what is the best and the right option to follow,” he said. “And then we consult on how to implement that option. This is our mandate.”

That’s an approach that requires the public to take, on faith, that Metrolinx knows what is “best and right.” And the agency’s actions—from insensitively placing a maintenance facility in the middle of Thorncliffe Park to the back-and-forth on a promised community centre at Jane and Finch to the endless delays on Eglinton—give Toronto residents little reason to grant the organization that faith.

Verster reports to the minister of transportation, and no one else. When things go wrong with, say, a multi-billion-dollar LRT project, the public is kept in the dark. “We’re not allowed to know any of the details,” says MPP Harden. “What I want to see at Metrolinx is more transparency, and full disclosure of all the things the public deserves to know.”

Metrolinx’s strong-arm approach—autocratic and secretive—is supposed to come with an implicit tradeoff. If Metrolinx is callous about community concerns, it’s in the name of efficiency. Rather than waste years indulging neighbourhood groups who might be overly sensitive about a little vegetation in Smalls Creek, some trees at Osgoode Hall, or a couple small businesses in Thorncliffe Park, all of which were destroyed despite community opposition, Metrolinx would be laser focused on building the transit system of the future, quickly and economically.

But in 2024, with the Finch West LRT and the Eglinton Crosstown behind schedule and over cost, it has become clear Metrolinx isn’t upholding that side of the deal. “There was a sense of ‘OK, this guy comes from Britain, which is way better at doing railways and transit than we are here in Ontario. So this guy’s going to be just what we need,’” says Wickens. “But as far as I can see, he’s never been involved in building major subway projects.”

Phil Verster did not agree to speak for this story, and Metrolinx did not respond to questions about his leadership. But his comments to the press have generally mirrored what he said in Scotland: building transit infrastructure is difficult, there would be pain, and that is the price of progress. Metrolinx’s own PR campaigns have echoed that sentiment. In a series of remarkably tone-deaf commercials released this winter, since removed, the agency casts anyone who complains about Metrolinx as entitled whiners who can’t see the big picture.

“This Metrolinx construction is killing me,” complains one actor. “I know, right? All for more transit and fewer cars, helping you breathe cleaner air and live a healthier life?” her friend responds, shooting the complainer the kind of withering look usually reserved for people who watch videos without headphones on the bus or refuse to pick up their dog’s waste. “It’s killing you,” she says, voice dripping with disdain.

It was a rare moment of clarity. An organization’s contempt for its users is usually hard to pin down—something you intuit based on its actions or inactions. But here it was in plain English, and put onto film at taxpayers’ expense.

People didn’t want another explanation of exactly how complex it is to build a transit line; they wanted to know when they can take it to work.

In early December, Metrolinx finally offered media members a glimpse of the Eglinton Crosstown. Reporters milled around the station entrance, dorkily wearing hardhats, when Verster suddenly appeared from the stairs below in a suit and safety vest. “Welcome to Eglinton West,” he said, sounding like a less enthused version of Richard Attenborough in Jurassic Park.

The tour was a PR event, intended to give the media, and thus the people of Toronto, a glimpse into the awesome scope of the project, and the difficulties that came with it. That felt, more than anything, like a fundamental misreading of public desire. People didn’t want another explanation of exactly how complex it is to build a transit line; they wanted to know when they can take it to work.

Walking through the station—cavernous and genuinely impressive, with LRTs humming past and disappearing down the tunnel—Verster was mostly content to let others speak. When it came time to take questions, he moved into what has become his boilerplate response. “We will declare an opening date for the Eglinton Crosstown project. But we will do so three months ahead of opening day,” he said. “We are finding and fixing issues and defects, and once we are satisfied that we’ve got the risk of those contained, we can announce an opening day. But not before.”

The one moment when he seemed most engaged was midway through the tour, when a TV reporter looking for some B-roll footage asked about a technical matter. Part of the reason for the delay, Verster had said, was that there were points where the track was very slightly misaligned. Was there anywhere on the tracks, the reporter wanted to know, where a camera could actually capture the discrepancy? Verster visibly perked up. The separation, actually, was tiny, he explained. “One millimetre, two millimetres, you can’t see it.”

“OK, got it,” said the reporter, ready to move on.

Verster leaned in, eager to get into the details. “The thing to think about, when it’s too close, if you think of the wheel, the wheel has got a flange on the inside,” he said. He gestured with his hands, miming a wheel rotating down a track, explaining the way it could climb up, derail, with just the smallest separation.

On the smallest scale—talking wheel flanges and ventilation systems, the genuinely important stuff of engineering—Verster could be a compelling speaker. It was easy to see how, in a conference room of politicians and bureaucrats, his technical expertise and bluster could inspire confidence.

At the largest scale, too, speaking in generational terms, Verster could paint a compelling picture of a future Toronto that would be more connected than ever. The transit lines being built today are long overdue. Twenty years from now, it’s possible that those grousing about Verster will look as short-sighted as the whiners from the Metrolinx commercials, unable to see the forest for the trees. “In the long run, if we get there, if the projects get built, and they work, we’ll be really, really glad for this era,” says Shoshanna Saxe.

But how we get there matters. The way that people feel about that process has consequences. “The number one thing I’m worried about,” says Saxe, “is people look at Eglinton and say ‘Oh, we can’t build anything. We shouldn’t try.’”

A bulldozer is useful during one phase of construction. But when it comes to the real work of transit infrastructure—the delicate act of building, of getting community buy-in, of connecting things rather than tearing them apart—what you want is a more subtle instrument.

Correction—March 18, 2024: A previous version of this article cited an analysis showing ScotRail apologized to riders over 1,000 times in 2016. This has been corrected to say over 10,000 times.