Earlier this month, Toronto City Council passed changes to their approach to Vision Zero, the multi-million dollar safe streets initiative started in 2016 that has, so far, yielded inequitable results in its mission to reduce injuries and deaths in traffic collisions.

Vision Zero is an internationally recognized approach to mitigating risk, so named because its aim is to create a city where zero people die in vehicle collisions. It argues that safe streets are dependent on infrastructure and design, rather than individual actions, and it’s the responsibility of city builders to design streets that make collisions near-impossible.

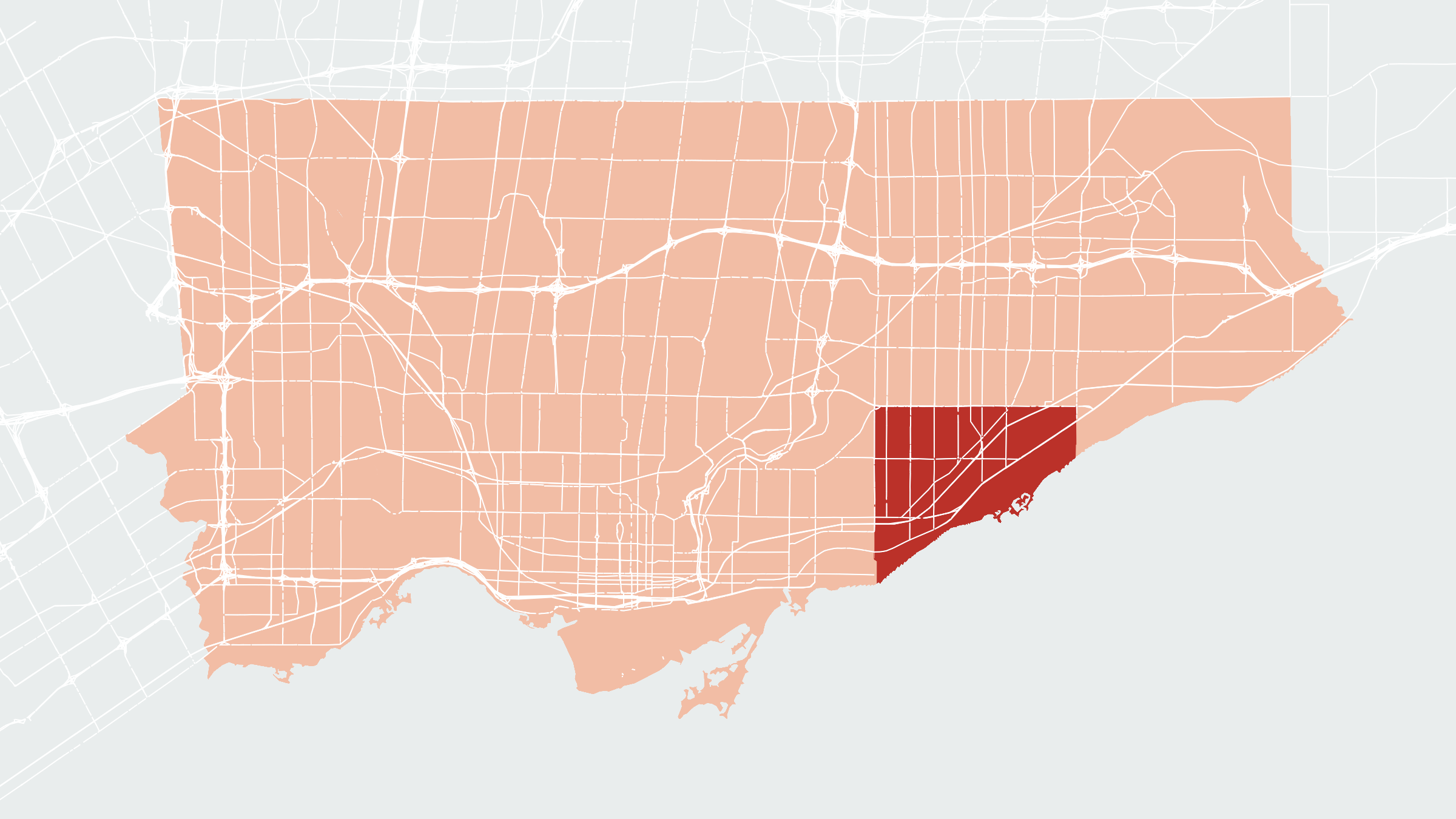

Ahead of the fall 2022 municipal election, however, a months-long investigation by The Local on the city’s Vision Zero program revealed a reactive, inequitable program in which road safety improvements were largely being built in wealthy, white neighbourhoods, while the city’s most vulnerable residents were being neglected.

That’s largely because Toronto’s Vision Zero program relies heavily on requests made by the public, and neighbourhoods with lower-income and more racialized populations—who don’t necessarily have the time, know-how and comfort to petition their city councillors—have historically made fewer requests, and thus received fewer safety improvements, despite facing higher rates of risk factors like speeding. In addition, in a system that relies on proactive councillors, some may prioritize the happiness (and votes) of drivers over pedestrians and cyclists and be less inclined to introduce road safety improvements that appear to inconvenience drivers.

The changes passed on November 8 were meant to begin to address some of the flaws in that system, and affect community safety zones, traffic-calming requests and enforcement of impaired driving and speeding rules. While the changes do make it easier to implement road safety improvements upon request, they do so largely by eliminating existing redundancies in the process—there isn’t much that’s innovative or outside-of-the-box to address the policy’s equity issues.

In the old system, residents had to collect signatures and petition their councillor to request traffic calming measures like speed bumps. Now, infrastructure changes can be initiated by the councillor independently, or by city staff who proactively identify sites in need of improvement. But in reality, this was already the way speed humps got built in many cases. Councillors could choose to waive the petition requirement if they felt it unnecessary, and many of the city’s most active councillors did.

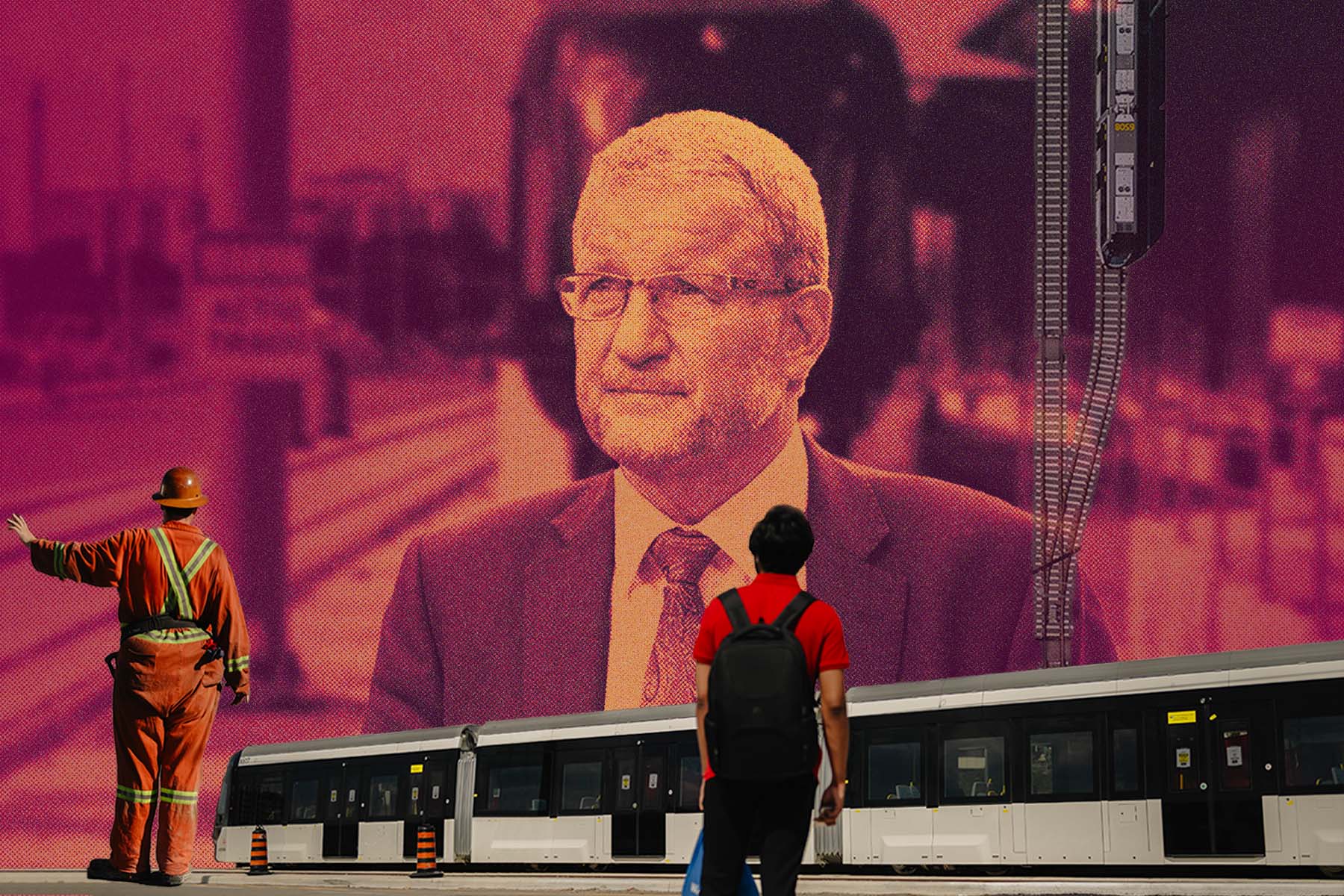

In a sense, this new policy mostly formalizes what some councillors already knew to be the best approach. “We’re removing barriers, we’re making it easier to clear the threshold to make the road safer,” says Brad Bradford, councillor for Beaches-East York, who The Local’s 2022 investigation found to be the most active of all Toronto councillors when it came to implementing road safety improvements.

In fact, part of the review and improvements brought forward this year are in response to a motion Bradford initiated last year. These new changes save time, effort and red tape.

“That’s been a frustration for a lot of people,” says Bradford. “Despite accidents, and in some tragic cases fatalities, it’s still very difficult to satisfy transportation requirements to do the right thing and make the streets safer.”

Similar changes have been made to the assessment criteria used by city staff to decide whether a safety measure should be implemented: there are less stringent requirements about the minimum number of cars using the road, the observed rates of speeding and the characteristics of the road itself. Under the previous policy, staff and councillors would engage in a bureaucratic dance—one rejecting requests, the other voiding the rejection and implementing the safety measures anyway. This change makes that back and forth a little less frequent.

In a sense, this new policy mostly formalizes what some councillors already knew to be the best approach.

We have yet to see any other major improvements to how the city handles pedestrian crossings, signals and stop signs—some of the more effective safety changes made in the city. These changes often take more planning, design and labour, which means Toronto has implemented fewer of these compared to things like safety signs and speed monitors. However, Bradford did butt heads with city staff about the criteria on stop signs, crossings and signals. City staff had initially declined to make any changes to them. In response, on November 8, Bradford introduced a successful amendment, making any location with even a single collision injury or death more eligible for safety improvements.

“It was a bit unexpected, to unilaterally change our warrants like that on the floor of council,” says Mateen Mahboubi, acting manager of Vision Zero projects at the city. It’s unclear what impact it’ll have on which locations are selected for safety improvements. “I think we’re still considering what the ramifications of that are.”

A second improvement framework, for stop signs, crossings and signals, is coming in 2024, Vision Zero staff say.

Essentially, this means that none of the current changes address the key weakness in the city’s road safety system—reactivity. Councillors will still often only find out about dangerous roads when their constituents call them, and the inequities around who is likely to do that haven’t changed.

The closest we’ll get to that for now is that staff are committing to consider equity factors when they decide how to prioritize changes. “When we have to make a decision of which locations to deliver first, let’s try to identify the locations that have the greatest need,” says Mahboubi.

The changes might bring in more requests than in previous years, but the department is prepared for them: COVID-era backlogs have been cleared, and this year’s budget for Vision Zero, $72.3 million, is more than any previous year’s since the program began. It’s not perfect—the city should be “more flexible, more agile, getting things done faster,” Bradford says—and we’ll only really see whether new, proactive measures are being implemented when the next report is released in 2024. But Mahboubi is confident the city is moving in the right direction.

“It’s a big system, it’s a slow moving system, and we are dealing with infrastructure that has been built to different standards for the last 80 years,” says Mahboubi. “We know that in 50 years, the city will look totally different. And everything we’re doing today is building us up to that.”