All Don Bates wanted to do that night was buy some gifts for his grandchildren.

It was October 30, 2021, the night before Halloween, and the 65-year-old had just been to the Dollarama near his daughter’s home, picking out little presents for the kids. It was raining when he left the plaza near Kennedy Road and Lawrence Avenue East in Scarborough. He walked north to the Beer Store to pick up the lager he had promised his brother, and then started his journey home, crossing mid-block at Kennedy Road, a five-lane arterial road.

He only made it across four lanes. Two steps before he reached the curb, Bates was hit by a minivan. The force sent his body flying into the air, landing 12 feet from where was hit. He died in the road, the gifts lying in a bag at his side.

Bates was one of 27 pedestrians killed in a traffic collision in Toronto last year. He’d been living in this city for just five or six years at that point—he had moved with his daughter, Julie Bates, from a tiny municipality in Port Hope called Welcome, where he’d been helping raise his grandkids. “They were my dad’s everything,” Julie describes. “My dad was like the rock of our family. He was my best friend in the whole wide world.”

“We just have to live now, every day, without him—because of something so stupid that could have been prevented.”

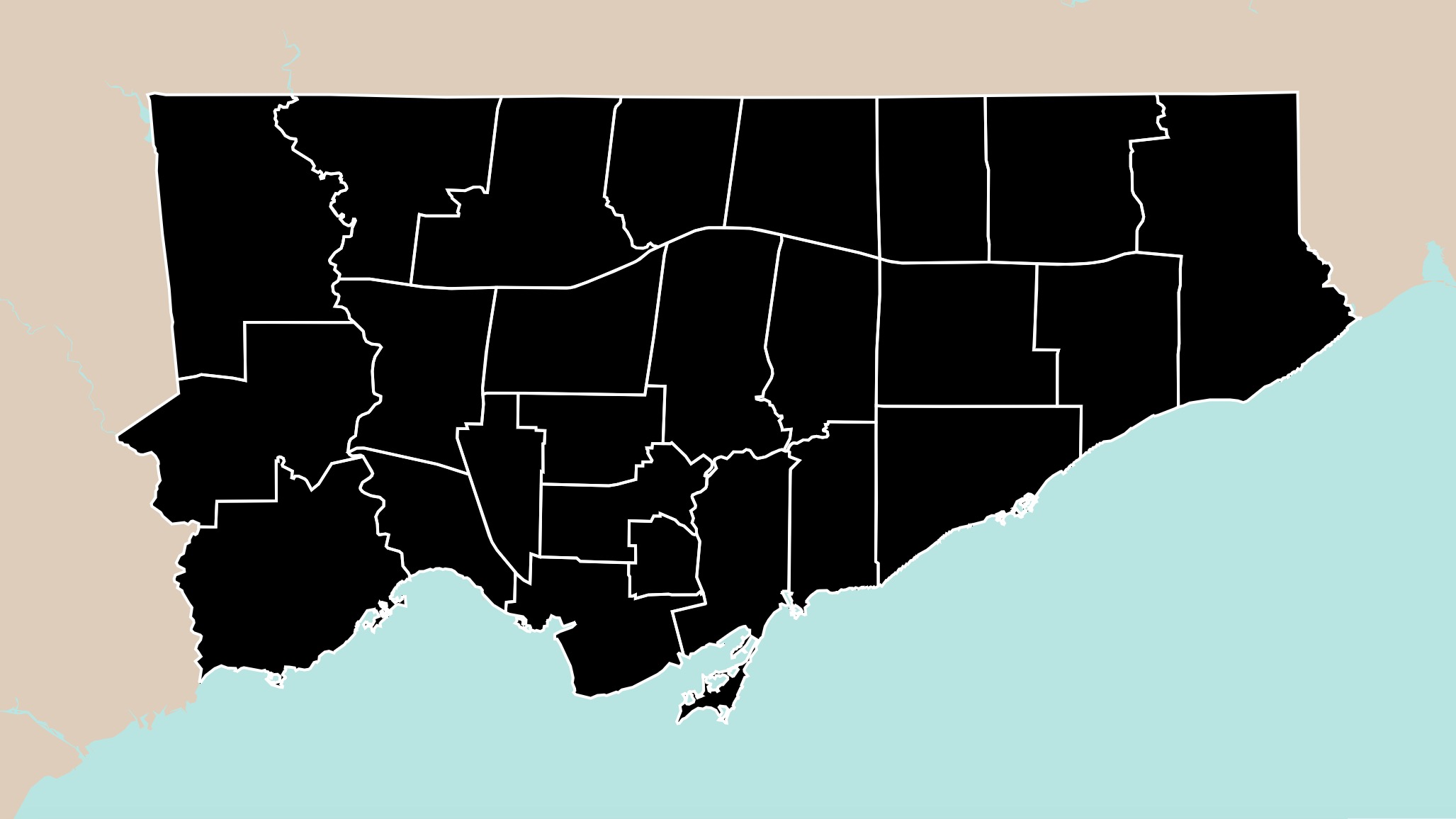

A Vision Zero city is supposed to be a place where not one fatality or serious injury is acceptable. It’s in the name. But every year, Toronto sees dozens of people like Bates killed on the road, and even more injured in devastating, life-altering ways, with entire networks of families and loved ones grieving what could have been. Now, The Local’s investigation into the state of Vision Zero in Toronto has revealed a system of road safety infrastructure that largely benefits wealthy, white residents of the city, while improvements in lower-income, racialized, inner-suburban neighbourhoods happen at a glacial pace.

The Local’s analysis of city council meeting minutes from the 2018-22 term found that councillors in and around the downtown core were far more active in advocating for road safety improvements than their peers from the inner suburbs, a finding confirmed by our analysis of where some of the most effective road safety improvements are being made. Additional data obtained through Freedom of Information (FOI) requests show that higher-income wards are more than 1.5 times as likely to request certain road safety measures than lower-income wards. These two factors, together, have meant that two versions of Vision Zero are unfolding in the same city, based on your postal code and the disparate priorities and political interests of your city councillor—and it’s costing the lives of pedestrians, cyclists, and motorists.

Join the thousands of Torontonians who've signed up for our free newsletter and get award-winning local journalism delivered to your inbox.

"*" indicates required fields

The first Vision Zero policy was born out of a sense of moral responsibility. In the mid-nineties, a number of children were killed in collisions in Sweden, stirring public awareness and concern about the state of the nation’s roads.

Those accidents gave new urgency to an ongoing conversation taking place among leaders and the private sector regarding collision prevention, says Ann-Catrin Kristianssen, a professor at Sweden’s Orebro University who has been studying Vision Zero on a global scale.

“It was very much this ethical perspective that we need to make sure that the numbers go down—not only by using a slogan, but also [through] systematic road safety work,” Kristianssen says.

The systems approach to road safety is more complicated than just aiming for zero—it specifically argues that road designers and regulators share the responsibility for crashes, fatalities and injuries, and it is therefore their duty to create roadways on which collisions are as close to impossible as possible. This includes measures like speed humps, raised sidewalks, points where the road narrows, mid-block crossings, automatic speed cameras, signage, and reducing the posted speed limit. If and where collisions do still occur, because of human error or recklessness, they should cause minimal harm.

“Everything should be based on the human body, and what the human body can handle,” Kristianssen explains. The grim arithmetic is clear: you have a more than nine in ten chance of survival if you’re hit by a car going 30 km/h. When that speed goes up to 50 km/h, your chance of survival plummets to 1.5 in 10.

Toronto adopted its own Vision Zero approach in 2016 under Mayor John Tory, and the policy was immediately criticized for not going far enough. Toronto’s Vision Zero focused on trying to slow down cars through automated speed enforcement and signage and improving existing signals and crosswalks (through head-start signals for pedestrians, which reduces the likelihood of collisions with turning cars, longer crossing times for seniors, and improved markings). It focused less on the strategies proven to be most effective—built infrastructure changes to reduce speed and severity of collisions.

Vision Zero 2.0 was adopted in 2019 after fairly unanimous agreement between city politicians and advocates alike that the initial iteration of Vision Zero “wasn’t working,” as Tory himself admitted in 2018. This second iteration, advertised as a more long-term plan, increased the number of built infrastructure changes and speed reductions and prioritized a more data-driven approach, but still failed to implement the city-wide speed reduction plan proposed by road safety advocates, and didn’t include any bold vision for bike lanes. In fact, speed limits on many of the city’s arterial roads were reduced just 10 kilometres an hour, from 60 km/h to 50 km/h—a reduction which does little to protect pedestrians or cyclists.

The total Vision Zero budget for 2017-2021 was $259.7 million in capital and operating costs, though only $205 million was spent, owing to what advocates believe is a lack of adequate staffing. (When asked about the disparity, the city said $205 million “represents an 82% spend rate, which is a strong performance in the context of the 2021 capital spend rate.”) Critics compare the funding to the other major transportation project in the city: the $2 billion Gardiner Expressway rehabilitation. In the first five years of Vision Zero, the policy has received as much funding as the Gardiner will in a single year.

In the time since Vision Zero was first implemented, rates of road fatality and injury have decreased by a small margin—there were 21 fewer major injuries in 2019 than there were in 2017, though the number of deaths stayed high. By 2021, there was a 57 percent reduction in the rate of injury, but only 5 percent when it came to fatalities; and it’s difficult to say how much of that is based on the success of the policy and how much was because of reduced traffic during the pandemic. Either way, it’s not enough to consider the project successful. Between 2017 and now, there have been 1,674 serious injuries on Toronto streets and 337 deaths. The vast majority, in both cases, are pedestrians.

Aggregated data from major cities across Canada shows that Toronto’s rate of fatality or injury per capita is middling compared to cities like Vancouver and Ottawa, though it is higher than large cities like Montreal and Calgary. As of 2019, Toronto’s rate of fatality and injury were 2.3 and 12 per hundred thousand people, respectively. But that’s the point of Vision Zero—just because you’re not the worst in the country, doesn’t mean you’ve done your job. The goal is zero deaths or serious injuries.

Vision Zero is supposed to be an evidence-based solution. But in its current form, its success is dependent on councillors’ willingness to implement it, and the will of the public to bring forward concerns and petitions about their local streets. That’s where the city is failing: as long as it relies on politicians and residents to advocate for safety measures, it’s going to result in a patchy, inequitable network of safety measures scattered across the city.

Most of the city’s road safety policies and changes have to go through city council or local community councils for approval—either in the proactive sense, where they are proposed by city staff and approved by council, or in the reactive sense, when they are requested by members of the public and championed by councillors.

If a resident wants a speed hump, stop sign, or some other safety measure installed in their neighbourhood, they start by calling 311 or getting in touch with their city councillor, either individually or with a petition from their neighbourhood. The councillor then follows a winding, sometimes year-long bureaucratic process. They have to request a review from transportation services, which assesses whether the change is warranted. After the review, the city mails out a poll to residents to see whether they’re open to this change. Councillors can waive this part of the process if they want. In fact, if a review finds that a safety measure isn’t required, councillors can waive the criteria and have one installed anyway. For some councillors, this is an indication of whether they think the criteria for safety improvements are too strict; others say it’s a matter of playing politics.

Using key road safety search terms, The Local analyzed hundreds of meeting minutes and motions from the 2018-22 city hall term to see which city councillors were the most active in advocating for safety measures, and which were absent from the conversation. A pattern emerged, dividing the inner suburbs from much of the rest of the city: councillors serving wards in the old city of Toronto were far more active in pushing through road safety improvements than their suburban counterparts.

Councillor Brad Bradford has been the most active member of the 2018-22 council—in a single day, he once pushed through the approval of 23 different speed hump projects in his ward, Beaches-East York. Bradford has also done his fair share of waiving the city’s criteria for road safety installation and adopting what residents have petitioned for.

“How I make that decision is very simple,” he says. “The local residents on the local street know their street better than the bureaucrats at city hall. If they think traffic calming measures are necessary, I’m going to be there to support them, and move that through the machinery of government.”

Earlier this year, Bradford also brought a motion to council asking that transportation services work on an update to the criteria they have for installing road safety improvements. “Those are largely antiquated, they come from a time when the priority for transportation services was to move as many single-occupancy vehicles as fast as possible,” says Bradford. “That’s not our priority anymore.”

Councillor Josh Matlow also has one of the highest rates of getting safety measures implemented in his ward.

“It’s a very archaic process,” says Matlow. “A very ad hoc road safety approach by the city. A street can be safer if one person decides to go get a petition from the neighbours, and happen to contact their councillor, and then that councillor happens to be a councillor who supports road safety measures.”

Matlow has long advocated for a more evidence-based and objective approach. In 2014, he requested transportation services review the feasibility of reducing all neighbourhood and, where possible, collector road speed limits to 30 km/h, leading to the unanimous decision by the Toronto and East York community council a year later. In the years following, police-reported collisions decreased by 28 percent, and injury severity by nearly 70 percent, one study showed. It took four years and the introduction of Vision Zero 2.0 for city staff to propose making the same reduction across all residential neighbourhood streets in Toronto, and implementation of that measure is only expected to be completed by 2025.

Records of city council meetings reveal the same few names engaging most extensively with road safety implementation through the last four years—councillors like Bradford and Matlow, Ana Bailao, Frances Nunziata, Paula Fletcher, Mike Layton, and Joe Cressy—all clustered in and around the downtown core. The Local’s analysis also found that these councillors are generally more willing to waive city criteria and directly ask for improvements to be made than their inner suburban, and often more conservative, counterparts.

While the figures here are just a snapshot of the different road safety conversations taking place in community councils across the city, they still reveal a troubling inequity. A broader search of more than 30 keywords relating to road safety revealed that Toronto and East York council, representing the wards of old Toronto, discussed the issue more than all of the inner suburban community councils combined, and at an average of five times the rate of each individual suburban ward.

The inner suburbs, particularly Scarborough and North York, are suffering because of their councillors’ lack of advocacy on road safety. A Toronto Star analysis of collisions in the city found that 98 of the 100 most dangerous intersections in the city are in the inner suburbs, on arterial roads. At Kennedy Road and Lawrence Avenue East, the intersection near the site of Don Bates’ death, there were 138 collisions between 2014 and 2021. As the analysis pointed out, the design of these arterial streets is such that risks are higher: lanes are wider, crosswalks are longer, and there are more opportunities to speed than on a smaller downtown street. But these are solvable problems—if councillors are willing to have those conversations.

“Many of the councillors, shamefully, who represent those communities have not had the courage just to be honest with their constituents,” Matlow says.

“[Road safety] is not anti-car. It’s about making people safer, including people who drive,” he continues. “The narrative and the discussion have been mischaracterized by so many politicians who just kowtow to fearful reactions, rather than engage their communities.”

Kennedy Road and Lawrence Avenue East, the intersection near the spot where 65-year-old Don Bates was killed, is one of the most dangerous in Toronto. Aerial photography by Christopher Katsarov Luna.

For Etobicoke Centre councillor Stephen Holyday, it’s not that black and white. Holyday is the councillor with one of the lowest rates of requests for road safety measures and the highest rate of voting “no” to them on community council, voting down nearly 10 percent of the traffic calming motions seen by Etobicoke York community council between 2018 and 2022. These were mostly motions in which a councillor waives the city’s review results or criteria—but Holyday argues that criteria is necessary in order to prioritize the areas most in need.

“Interventions like traffic calming, speed humps, stop signs—it’s not practical or advisable to install them anywhere and everywhere. You have to have a methodology on how you prioritize where they need to go,” he says.

When it comes to the disparities between the inner suburbs and downtown Toronto, Holyday points out that councillors will bring to the table what their constituents report to them, and road safety implementation needs to be evidence-based and backed by both the city’s transportation services reviews and public will.

But there are serious problems with relying on residents to advocate for improvements in their communities.

In theory, any member of the public can request changes known as “geometric safety improvements,” which are modifications to the built infrastructure in your area, like the addition of speed humps, new sidewalks, lane narrowing, or request a Watch Your Speed (WYS) sign that flashes drivers’ speeds at them to encourage slowing down. But who is likely to have the time, capacity, and know-how to petition their councillor for a speed bump?

The Local obtained ward-specific breakdowns of requests for geometric safety improvements and WYS signs through FOI. Both show that wealthier wards are far more likely to make these requests than lower-income communities. Residents in wards with incomes above the city’s median were more than 1.5 times as likely to request a WYS sign in their neighbourhood than residents from poorer wards, with wealthier wards averaging a rate of 87 requests per 100,000 residents from 2019 to 2022, and lower-income wards averaging just 57.

These differences speak to the power of advocacy, which is closely tied to the socio-economics of neighbourhoods, and not some suburban/urban divide when it comes to the value of road safety. Holyday’s Ward 2, a relatively wealthy and white suburb, had the highest rate of requests for WYS in the city, at around 35 a year. In Ward 22 — Scarborough-Agincourt, a suburb on the other side of the city where over 80 percent of residents are visible minorities and income is well below the city median, there were just 3.8 requests a year.

This pattern is repeated for all kinds of citizen-driven road safety requests. Take geometric safety improvement requests, which include things like speed bumps and engineered changes to roadways, like raising curbs or narrowing lanes—wealthier wards are 1.6 times more likely to make successful requests than poorer wards.

When so much of the city’s road safety response is left to the discretion of councillors and citizens, you get a profoundly unequal landscape of road safety improvements in the city. A 2020 study of the distribution of traffic calming measures in Toronto revealed not only disparities in the number of measures implemented in low-income versus higher-income neighborhoods, but also in the rate of collisions involving children, which is more than five times higher in poorer areas.

“We talked to the City about why this is happening, why richer areas are getting the speed humps and poorer areas aren’t,” says Linda Rothman, author of the study, who teaches at Toronto Metropolitan University and is a senior researcher at SickKids Hospital.

“During the time frame of the study, installation of speed humps was generally request-based. So if you asked for a speed study done in your neighbourhood, you got it,” she adds.

The problems with relying on citizen requests are obvious: lower-income and racialized people face greater job precarity, work longer and more gruelling hours, and often have to care for multigenerational households. They may face language barriers, or may not feel comfortable reaching out to their city councillor, or even know that the option of making a request is available to them.

“So a request-based system does not work,” Rothman says.

The Local sought to confirm these disparities against the City’s Vision Zero map, but when asked, the City said they had encountered a technical error which meant “speed humps installed in 2021 and 2022, and potentially other improvements installed during these two years, are not being displayed.” However, The Local’s analysis of data regarding road safety measures implemented between 2016 and 2021 confirms that downtown wards have historically received the most effective road safety improvements at a rate far greater than the suburbs. Davenport and Toronto-Danforth, for example, had individually implemented as many traffic signals between 2016-2020 as the entirety of North York. Speed reductions downtown numbered in the hundreds per ward, while suburban wards only had a few dozen each.

The City says that Vision Zero 2.0 aims to address the crisis of road safety in the suburbs and employ a more data-driven approach. Staff say they’re cognisant of trying to avoid making the same mistakes this time around: traffic calming projects rolled out this year, for example, were done more proactively, with council and public requests making up a smaller proportion of the overall project. And the city is building road safety improvements into the regular road maintenance projects scheduled across the city.

“We’re very much being mindful of the historical speed hump program,” says Sheyda Saneinejad, manager of the City’s Vision Zero projects. Especially with the ongoing review of the traffic calming policy, initiated by Bradford, Saneinejad says they’re aiming to prioritize a data-driven approach.

“It also significantly depends on the will of council, and the level of support for those kinds of decisions, because some of this has to do with changing what is delegated to staff versus what is within the decision-making powers of councillors themselves.”

In 2019, city staff recommended that they be given the right to approve new sidewalks without having to go through council, only for suburban councillors Holyday and Mark Grimes to raise motions against that wholesale authority. If Vision Zero 2.0 is meant to learn from past mistakes, then it clearly hasn’t, because the biggest flaw has been the City’s inability to take politics out of road safety.

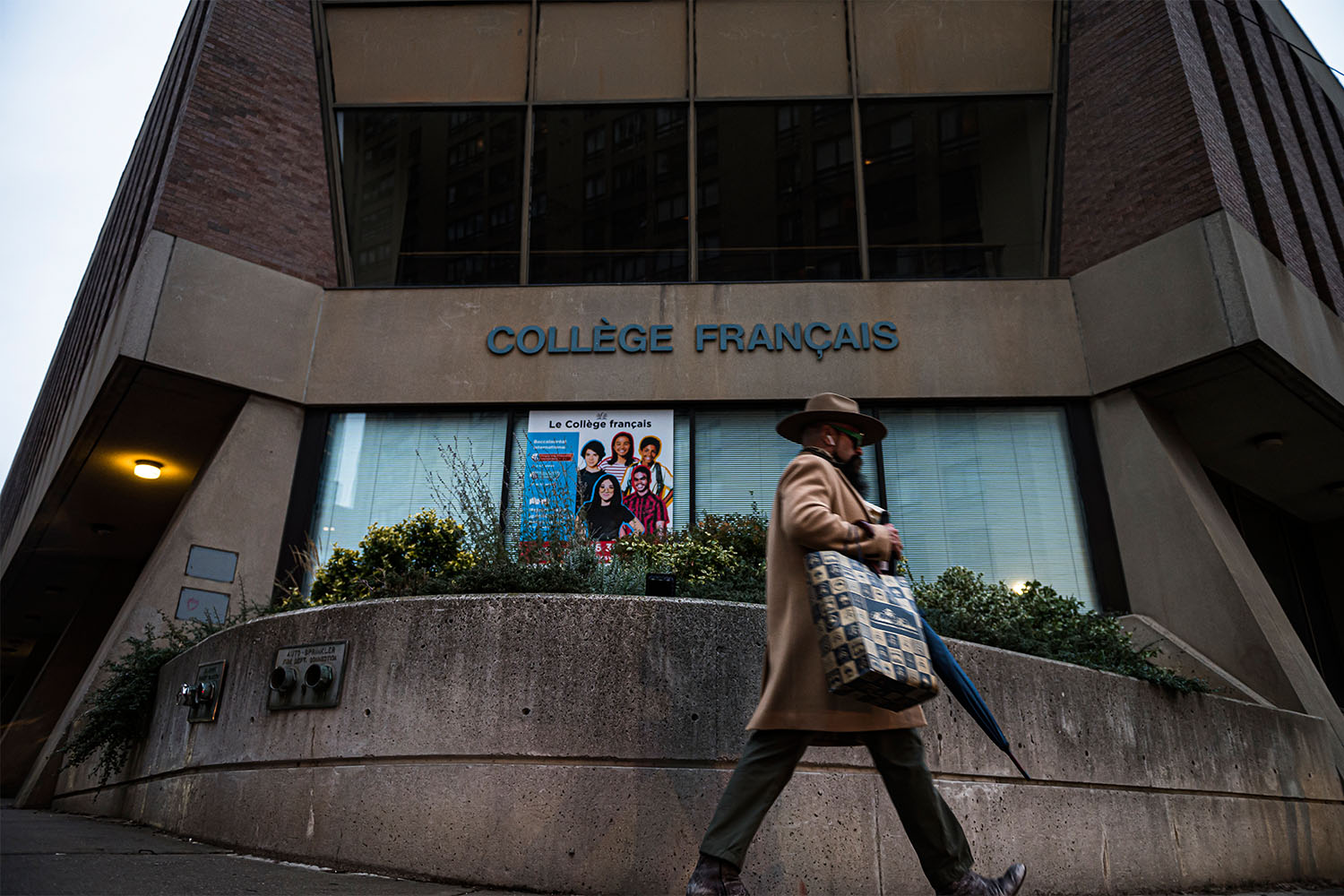

It was a child getting hit at a crosswalk that finally persuaded Deborah to become a crossing guard.

In 2010, Deborah (who is using a pseudonym, as crossing guards are prohibited by their employers from speaking with the media) became a crossing guard after hearing of a child being struck by a car in North York. The crossing guard on the scene had sprung into action, attending to the child, stopping cars from passing by, and managing the scene.

“I felt like that should be something I do. She saves this kid, I should do the same thing—give back to the community,” she says.

In the nearly thirteen years since, Deborah has worked as a crossing guard outside a North York elementary school. She’s warm, beloved by the students—she knows them all by name, and they know her in turn. Every school day, for an hour in the morning, an hour at lunch, and an hour and a half at the end of the day, Deborah essentially holds these children’s lives in her hand.

The first time Deborah was nearly hit by a car, the bumper of the approaching vehicle stopped just inches from her knees. She felt herself go into shock, not processing what had happened until the end of the day. She cried all the way home.

“I was so terrified. I was thinking, ‘Why can’t these people obey the signs? Why can’t they watch the light? Why not?’ But nobody cares anymore. Nobody cares,” she says.

That was in 2010—in the time since, she’s experienced more near-misses, and seen other people get hit, including children. She wars with rash drivers daily, and is subjected to their speeding, running of red lights (the more apologetic drivers claim the sun makes the light hard to see, she says), swerving lane-changes, and intolerable, unending distracted driving.

“They give me the finger, tell me the fuck off, call me a wannabe cop. And I’m thinking, ‘I’m doing a job!’ I’m here to get the kids across safely, get adults across safely,” she says. “You have the freedom to drive, but these people have the freedom to walk across the road, too. You have to share it.”

Deborah works outside of a North York school The Local identified as having one of the city’s highest rates of speeding, according to our analysis of Watch Your Speed sign data. The last four years of speeding data from school zones shows that the problem is disproportionately worse in the inner suburbs than downtown. North York, in particular, is home to four of the top five worst zones, where a majority of drivers are going 20 km/h over the speed limit. The suburban school zone with the highest rate of speeding in the city, located near Bayview and Finch Avenue East, saw 2.5 times more incidents of speeding over the last four years than the worst downtown site.

The act of speeding near a school zone feels like a particularly egregious moral failing—but it’s happening thousands of times a day in the city. Parents do it after dropping their kids off at school. Late workers try to avoid traffic by cutting through a quiet neighbourhood. An effective Vision Zero policy would mean better road design, so that individual intentions matter a little less. But it doesn’t preclude the need for a social shift in our perceptions of who owns the road.

Cars are fundamentally tied to self-centric ideas of convenience, comfort, wealth, and status. They’re seen as the primary reason roads exist, while public transit, cyclists, and pedestrians have to fight for access.

Many of the policy makers deciding how safe Toronto’s streets should be also decide how much money goes into the city’s transit infrastructure, and the same patterns of disparate priorities emerge. The inner suburbs have the most dangerous and least walkable streets, and the worst transit access—leaving no choice but to get in your car, if you can afford one.

“Cars versus bikes, suburbs versus downtown, there’s all kinds of conflicts that are completely unnecessary,” says Gil Penalosa, a leading challenger to John Tory in the upcoming municipal election. An international parks ambassador and designer, and founder of 8 80 Cities, which advocates for accessible and equitable cities for all ages, Penalosa’s prior work has specifically focused on designing shared roads for all users.

In the 1990s, Penalosa worked as the parks commissioner in Bogota, Colombia. During his tenure, he revamped and expanded fivefold the city’s Ciclovia or Open Streets program—an initiative that sees the streets closed to cars every Sunday and on holidays.

“It’s good for the environment, for mental health, for physical health. It’s good for economic development. And it’s good for social integration,” says Penalosa. “It’s the only place where people meet each other as equals.”

The conflict between road users, Penalosa argues, is a relic from Rob Ford’s mayoral tenure and his notorious fight against the supposed “war on cars,” that has been perpetuated by Tory.

When reached for comment, a spokesperson from Tory’s team said, “As he has said many times, the Mayor wants our streets to be as safe as possible for everyone who uses them, whether they are walking, riding a bike, taking transit or driving a vehicle, in every part of the city.”

“The data-driven approach particularly of Vision Zero 2.0 that the Mayor led City Council in supporting will ensure safety changes to roads and intersections are being made in all parts of the city where they are needed most.”

If elected, Penalosa plans to implement an Open Streets program on Bloor, Yonge, and Lake Shore every Sunday of the summer—part of a shift away from seeing cars as the centre of urban life. He also wants to introduce a city-wide 30 km/h speed limit on almost all Toronto streets, not just residential roads—a policy popular in several European cities, including Paris, which instituted the limit last year.

That’s one of the key policy changes advocates have been arguing for in Toronto; another is an increase to the Vision Zero budget. Councillors like Josh Matlow have argued for a more thoroughly data-driven and evidence-based approach to road safety, that doesn’t rely on councillors taking the initiative—but if that’s going to happen, the city’s Vision Zero team is going to need greater staffing, power and resources.

Intersection of Dundas Street West and Dupont Avenue, where Stephanie Blackmore was hit by a car six years ago that changed her life. Aerial photography by Christopher Katsarov Luna.

Any improvements to Vision Zero will come too late for victims of traffic accidents like Stephanie Blackmore. At 3:00 a.m. one morning in August 2016, Blackmore was cycling to her work at a bakery when she was T-boned by a car at Dundas Street West and Dupont Avenue. She flew through the air and landed on her bike and her backpack; her pelvis was fractured, the cartilage in her hip torn, and she had a concussion and whiplash.

In a single instant, the life she had created for herself was torn away. Blackmore had spent the ten years prior pursuing her craft as a baker. She finally had her dream job as head baker at her dream bakery. After the crash, all of that disappeared.

“I had to give up on my literal life’s passion,” she says. ”You’re supposed to push yourself through some pain, but when the pain becomes so unbearable that you can’t grip anything, can’t [live] your daily life, that just became impossible… I’m still grieving over that loss.”

Blackmore struggled to keep a job, or find one that wouldn’t force her beyond her physical and mental limitations. She had to jump through insurance hoops, navigate the bureaucracy of filing for disability benefits, and go through a demanding civil suit that took up the better part of six years. She couldn’t go outside without fear and anger overwhelming her when she saw unsafe driving and close calls. She had to move back to her quieter, safer hometown. Her marriage ended. She was suicidal, and still experiences chronic pain and PTSD.

“I was just losing my mind, every day,” she says.

Blackmore is six years into a grieving process that will last a lifetime. The same goes for Julie Bates and her siblings, and the hundreds of people affected by traffic collisions every year in Toronto. The year Blackmore was hit was the year the Vision Zero policy was voted into existence by city council. Since then, people have continued to be devastatingly injured and killed at a rate far faster than the city’s road safety progress. The changes aren’t difficult to imagine—all that is absent is the political will. What if Don Bates had had a safe, nearby crosswalk to cross at, or if the driver approaching him was forced to slow down? What if Stephanie Blackmore cycled to work in a city where roads were shared equally, and safe for everyone?

Instead, in the six years since Blackmore’s crash, all that’s changed is the colour of the pavement in the bike lane at the intersection where she was hit. Drivers still weave into it and cut through it. And when Julie Bates visits the site of her father’s death nearly a year later, nothing seems any different. It’s just a sea of cars, speeding by.

This investigation is supported by the Data-Driven Reporting Project. In keeping with the principles of the project, The Local has published the results of our FOI requests to the city—find them here.