On a mild morning in early November, just two weeks after their local school trustee election had been voided in dramatic fashion, ten people from Toronto’s French school community sat around a big table by the window at a pub on the Danforth to figure out their next move.

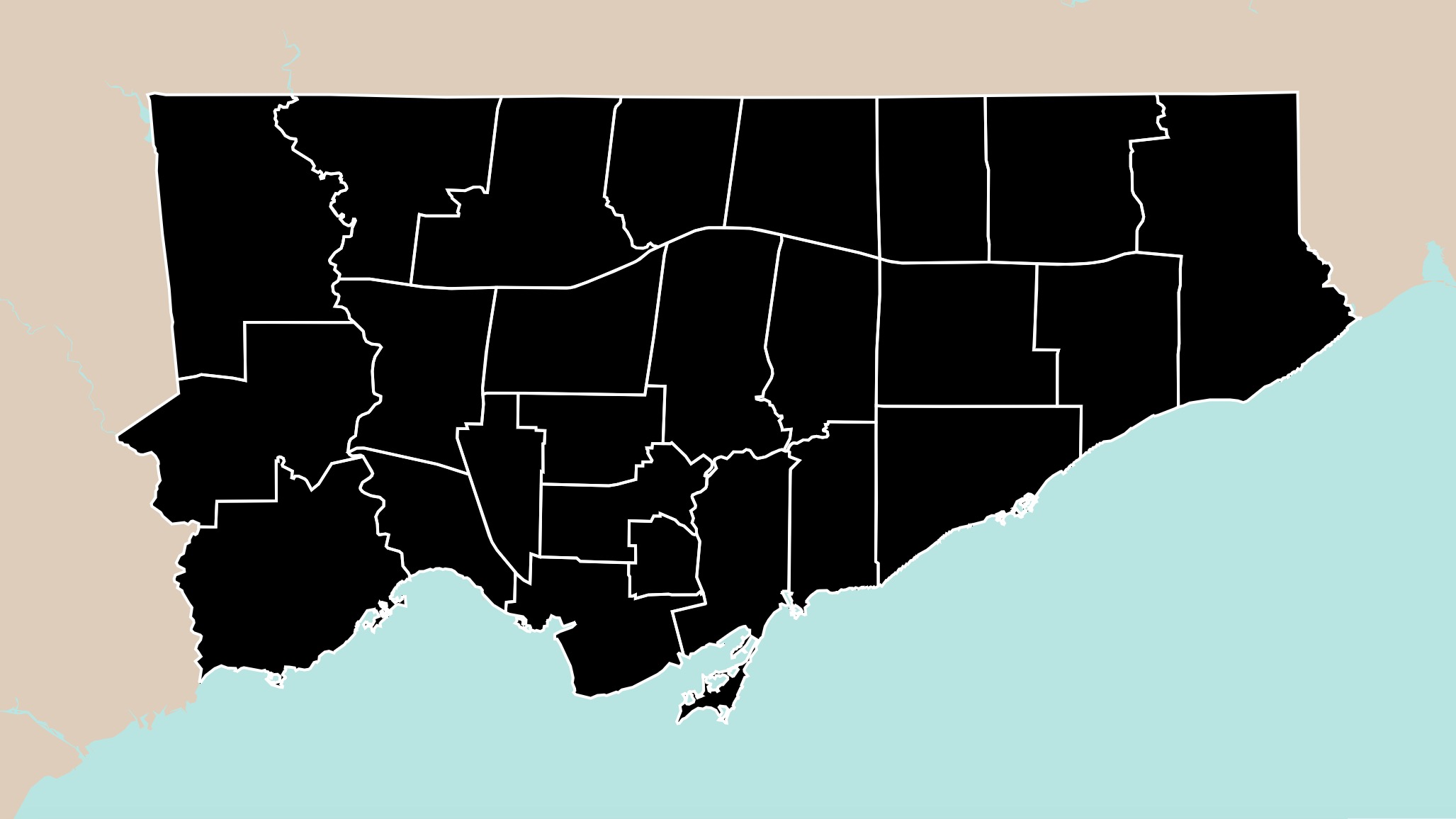

Last August, in the final days of the nomination period, the names of two mystery candidates appeared in the Ward 3 race in Toronto’s French-language secular school board, Viamonde. Parents and community members, including some of the people meeting in the Danforth pub, immediately started asking questions. Who were these people who didn’t seem to be running a campaign and didn’t even have an internet presence? After weeks of investigation, they learned neither candidate spoke French. The Local reported on one of the candidate’s troubling views on Pride celebrations, LGBTQ2+ terms, and Truth and Reconciliation in schools. Then community members found out (alongside the candidate himself) that a person running for trustee was ineligible to run or even vote in Viamonde because he was not a French-language rights holder, voiding the entire election. A trustee race in the French-Catholic school board MonAvenir was also voided when two of the three candidates running in the board’s Ward 4 were found to be ineligible.

The meeting at the pub was, in part, to figure out what these community members could do now that they’d been given a do-over. Cameron MacLeod, a tech professional and parent in the ward, had brought together people who wanted to run for trustee and invited former Viamonde trustee Pascale Thibodeau, who gave attendees an overview of how to run an election campaign, trustees’ role in relation to the board and public, how to create contacts with other levels of government, and a breakdown of the workload.

The meeting happened in the days leading up to the nomination period. Now, days before the January 23 by-election, seven candidates are running for trustee in Viamonde Ward 3. (This election, all candidates say they are fluent in French as a primary language). It’s a huge field for a trustee by-election in a French school board that many people in the city don’t even know exists. Since 2006, no French school ward election in Toronto has exceeded four candidates, and eight trustees have been elected unopposed. In 2022, the three French school elections that weren’t voided acclaimed incumbents.

A groundswell of organizing has galvanized the community, inspiring action both from those who were involved before and those that weren’t. Five of the seven candidates running say this is their first time vying for elected office. Six out of seven are parents with children either eligible or attending a French public school. Almost all candidates say they’re running as a direct response to the events of the fall. A lawyer, a teacher, a former Toronto French school student, a media professional, a full-time parent—all have jumped into the race, each saying they’re thrilled to see so much interest in local democracy and their community.

See All Viamonde By-Election Candidates

Candidate Tracker is your go-to place for fact-checked biographies of all Viamonde Ward 3 — Centre by-election candidates.

Two current candidates, Anna-Karyna Ruszkowski and Serge Paul, attended the November meeting, although both say they had a strong interest in running beforehand. Paul ran for French public school board trustee in the Durham region last October, and Ruszkowski also ran in the region in 2018. Two people that attended the meeting but decided not to run have now joined Ruszkowski’s campaign.

Paul and Ruszkowski are joined in the race by Pierre Lermusieaux, a lawyer and first-time trustee candidate who, like several others running in the by-election, says that last October’s voided elections pushed him into action.

Lermusieaux has worked in French-language rights law since 2013 and is a parent of a toddler whom he and his partner plan to enroll in Viamonde. The founder of a human rights and employment firm in Toronto, Lermusieaux was part of the legal team representing B.C.’s sole French school board (Conseil scolaire francophone de la Colombie-Britannique) and parents in a 2015 Supreme Court case and subsequent 2020 appeal for equal educational services.

The challenge was based on the same charter rights that ultimately disqualified October’s candidates, and remains the driving force behind issues for this municipal by-election: minority language education rights.

Under the charter, both majority and minority language schools (in this case, English and French) need to be substantively equal—meaning that they should not just be treated the same, but that the “quality of services be essentially equivalent,” even if it means giving the minority language schools more.

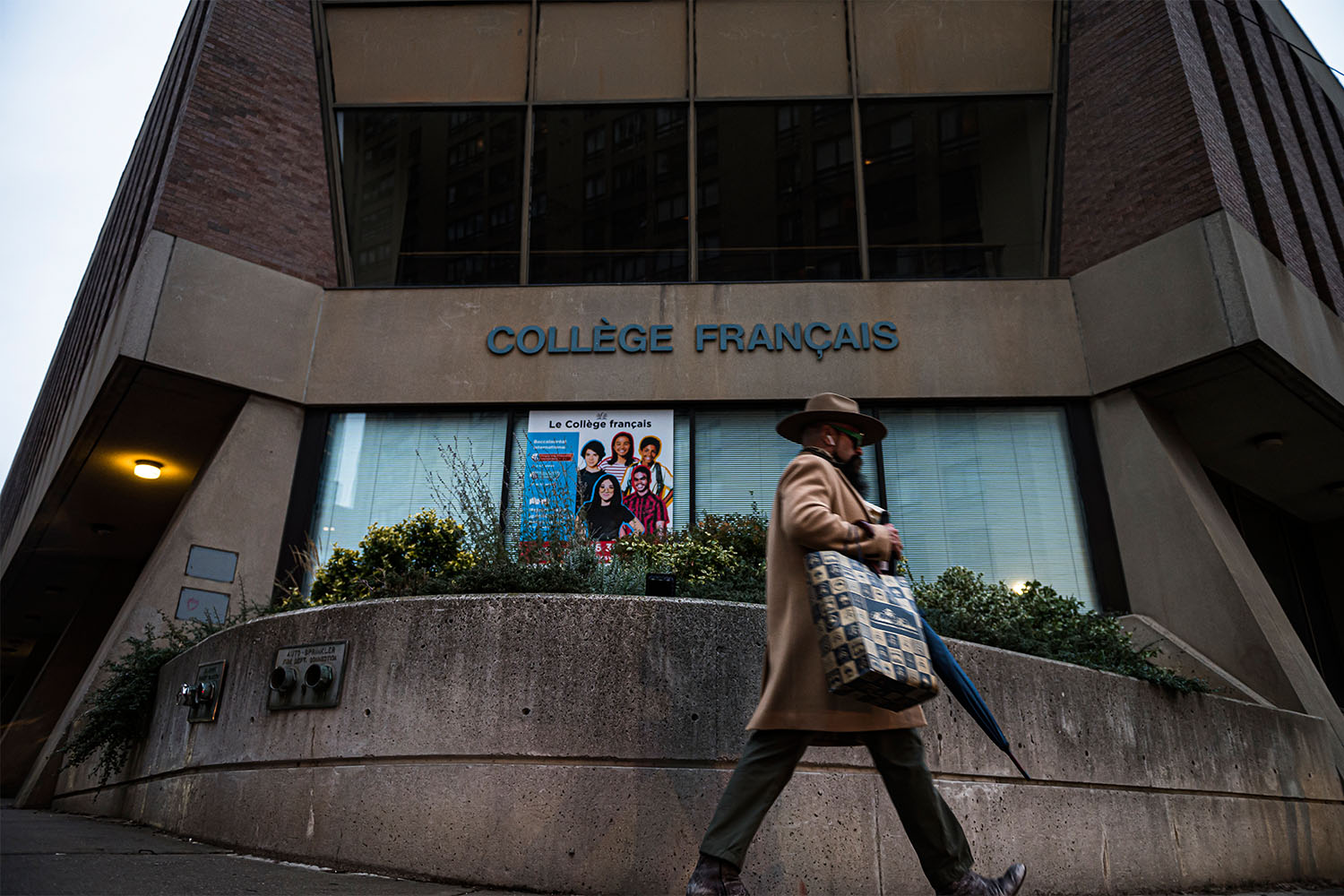

For Lermusieaux and other candidates vying for trustee, the question of equality is at the centre of one of this race’s biggest issues: plans for the unnamed new Viamonde high school located in a former TDSB building near Greenwood and Danforth. It’s a school that community members have spent over a decade fighting for. And while the building is set to open this fall, it doesn’t have a designated greenspace or school yard, unlike the English Catholic school nearby. The community’s fight to take over an adjacent park highlights a mess of overlapping jurisdictions that any trustee vying for the position will have to navigate, and it’s one of the reasons for the community’s fervour in the wake of an election cycle in which they thought they might not have anyone to represent them.

Heidi Pospisil has been an advocate and active member of the French public school community in Toronto for about 15 years. She’s a founding member of Coalition de parents pour une école secondaire de quartier (Coalition PESQ), an evolving group of parents who have been advocating for a local French high school in the east end for over a decade. But she hadn’t seen anything like the community engagement that happened during October’s trustee election in a long time.

Pospisil says she saw action spread on Facebook and in person, moving beyond her group of “activist parents.” Before the election, she says, she felt her community had been asleep at the wheel.

“We were in our COVID slumber, and we just thought politics would happen by itself,” she says, “I think what I realized is you can’t take an election off. When you care about something, you have to make sure someone’s at the table who represents you.”

And it’s not just parents that have woken up for this by-election.

Alex Nanoff, a 31-year-old former Viamonde student, says he’s running as a “product of the school board” looking to give back to his community. Nanoff says that for his generation of French-school-educated peers in Toronto—a fairly tight-knit group who attended the same schools from kindergarten to grade 12—the events of the past few months have been a shock. And seeing the saga unfold, Nanoff couldn’t shake the feeling that he could do more.

Nanoff is a public affairs specialist whose communication firm deals with governments, pollsters, and media organizations in both languages. “This system gave us so much opportunity. Many of my peers are actively working in both English and in French seamlessly in their current positions, and have hugely benefited from that,” he says.

“My generation needs to step up to the fact that we were raised in this system, we benefited greatly from the system. And it’s up to us to make sure that its vitality is preserved for the next generation of students.”

Despite his commitments, Nanoff himself faced a major barrier declaring his own candidacy due to his status as a renter. Despite Nanoff and his lawyers saying he’d been a supporter of the French public system since he was 18, city clerks told him he would have to validate his candidacy by filing his address on the property assessment list—a process, they said, that would likely take until 2024. Although Nanoff says the city may have been overzealous in the wake of the ineligible candidate debacle it’s a system, he says, that harkens back to land-owner-only voting.

Nanoff challenged the city’s decision with legal help and the involvement of the organization that represents all French public school boards in the province, and his candidacy was validated on December 21 of last year. But he thinks this challenge was probably only possible because of his knowledge and connections from working in politics.

“I can only imagine somebody who may otherwise have perfectly valid things to bring forward in the school board governance system that would otherwise be discouraged or simply not know where to begin when it comes to navigating this area,” he says.

Ultimately, though, Nanoff says he’s glad to see how many people are running this time around.

“I’m super encouraged that other people have stepped up to the challenge. I think that with the negative situation we found ourselves in the fall, this has really ignited the flame of political participation amongst members of the Francophone community. And I’m all for it.”

“We were in our COVID slumber, and we just thought politics would happen by itself”

In the aftermath of placing ineligible candidates on the ballot in October, the City says there have been small changes to the nomination process. The City of Toronto said that while nomination papers have always been available in both English and French, “the form was revised to include a more detailed acknowledgement of the French language rights and school support requirements under the Education Act” as a result of the voided elections. They also say that in this by-election, officials checked all candidates against municipal property assessment rolls to ensure they were eligible.

For the community, the voided election seems to have sparked more than just an interest in candidacy. Documents shared with The Local show that the number of electors on the voter list in Viamonde’s Ward 3 had increased by at least 632 electors as of late December (voters have to complete a form to indicate which school board they support based on their French-language rights and whether or not they are Roman Catholic. This is different from the English-public school board, TDSB, which is the default for voters who don’t indicate they support another school).

Although MacLeod expresses some concern that this number of candidates might turn the race into a “random number generator,” he says he loves that people want to contribute to the community—especially because it can be hard to stay engaged.

“The system wears everybody down,” he says. “We need to have energetic and maybe a little angry trustees because they have to push the board. They have to show the board that it is possible to do more. It is possible to do better. And when they’re tired, they have to step aside so that the next engaged, enthusiastic, angry trustee can step in. We work as a community.”