I never expected my dad would become my model for political engagement.

As a kid, I remember him spending hours chatting with his friends about the news. I made fun of the way he cared so intently about politics, deepening my voice to imitate the timbre he used when discussing the state of things back home in the Democratic Republic of Congo.

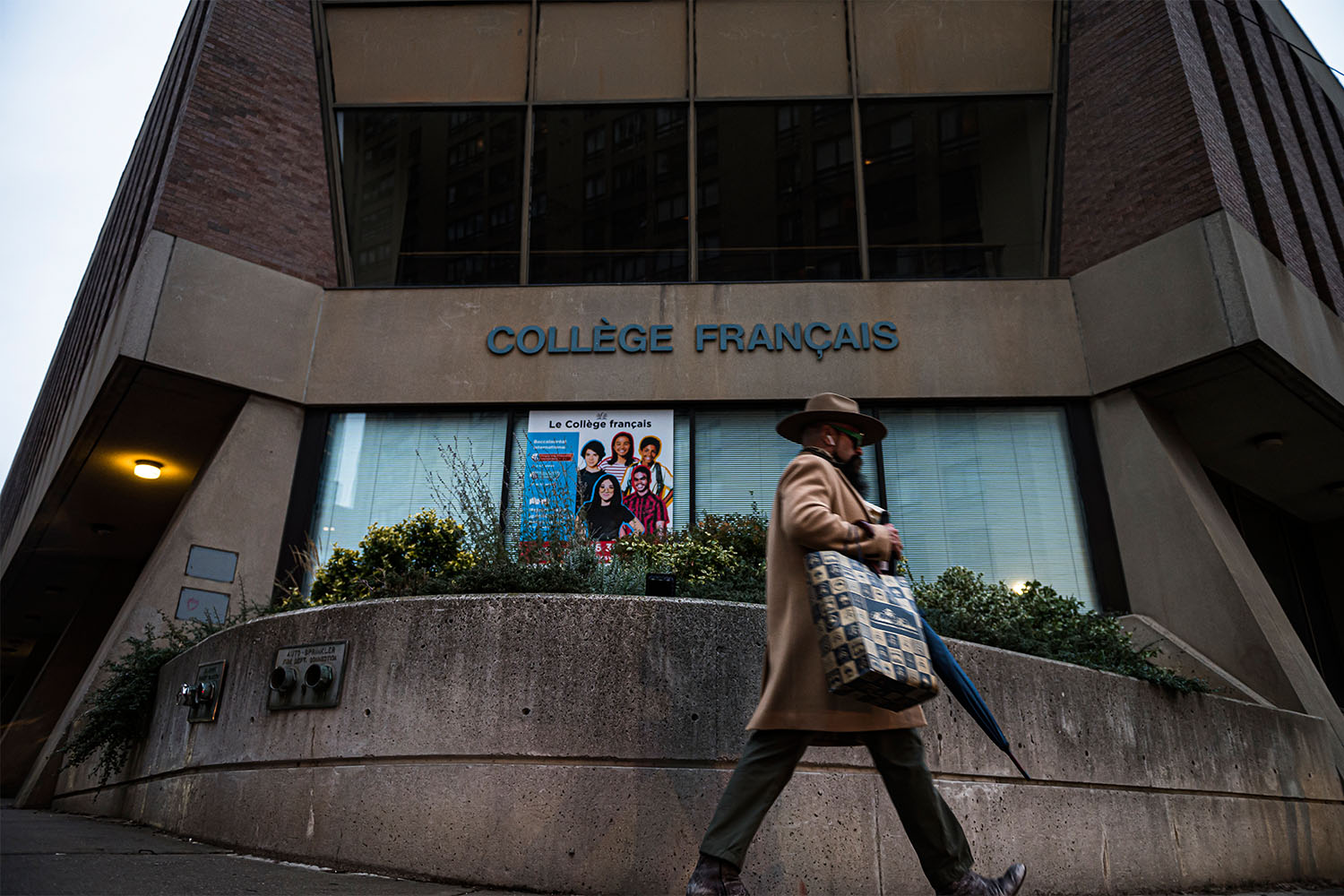

But when he moved to Kitchener, he poured himself into his community—opening up a local African beauty shop, sharing all he’d learned from the hours spent listening to Ici Radio-Canada Première or Radio Okapi, and showing new African immigrants around town.

As I got older, I learned to play a similar role in my own community. As a queer Black woman who grew up during the peak of Instagram and Tumblr activism, my political engagement is different than his, of course. For me, it looks like sharing and supporting friends’ and strangers’ mutual aid requests, filling up community fridges, and offering my skills, time, and support.

But while my idea of political action expanded as I got older, I realized that this wasn’t necessarily common amongst my peers. When I went to university I saw that for my classmates, many of whom were white and liberal, civic engagement meant one thing: voting.

I remember one conversation in the fall of 2020, six months into the pandemic and just before the federal by-elections, during which I sat in front of my laptop screen and tried to summarize my apathy towards voting in the fewest number of words.

“I just have very little faith in elections,” I nervously shared over a video call with friends.

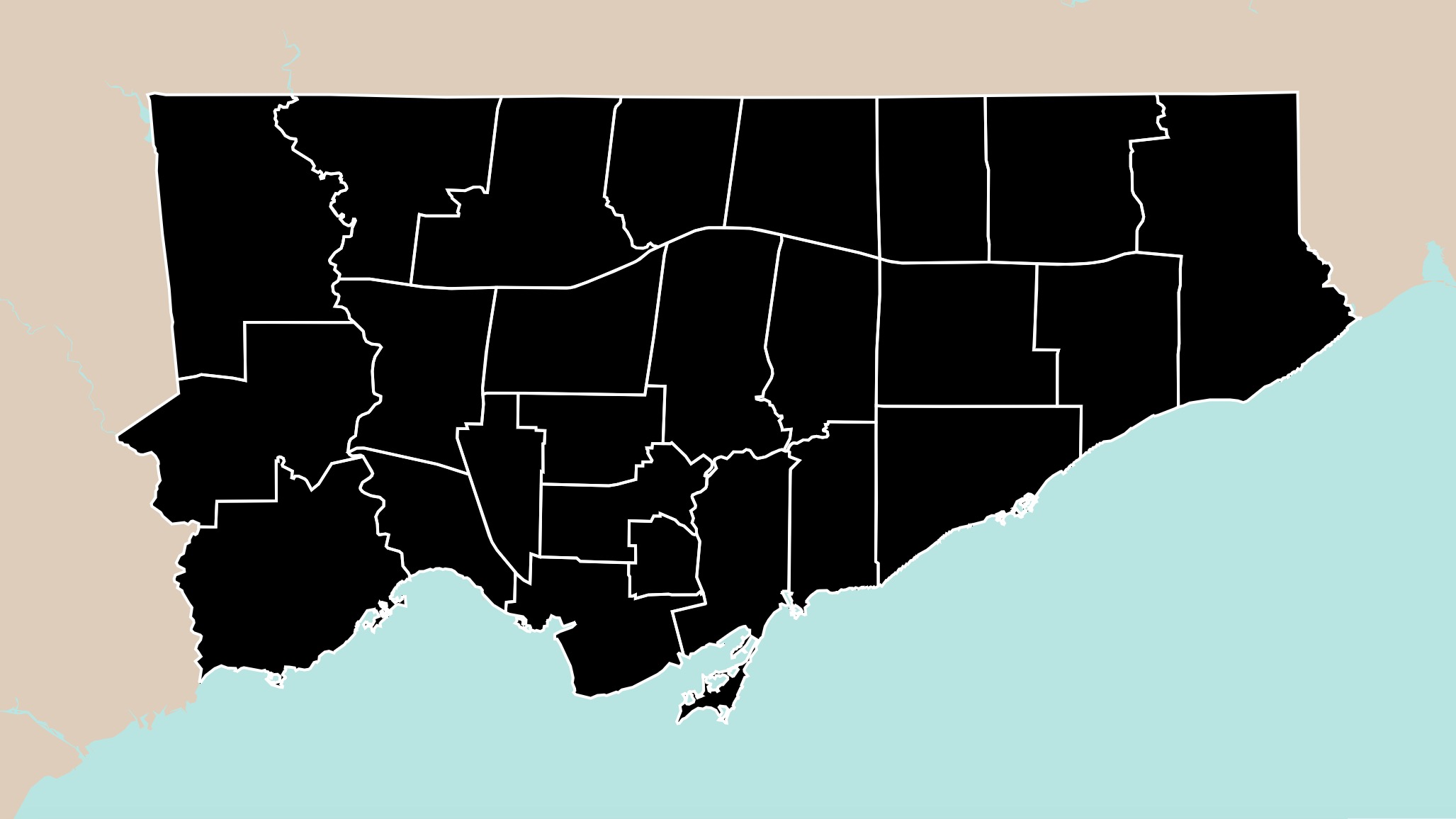

My comments came on the heels of the election of Doug Ford and the latest municipal vote. During that election, I had stayed informed—double- and triple-checking where I’d be able to fill out my ballot, encouraging friends and family to make it to the polls. I used Vote Compass to see what party aligned with my values. I sat in at a debate in my ward, Don Valley North, straining to hear any mention of solutions to houselessness, support for racialized people, or LGBTQ+ issues. That election ended with the re-election of John Tory and the sobering knowledge that the third-highest-voted mayoral candidate was a far-right white nationalist, one of three similarly aligned candidates that year.

So when my friend asked me why I felt apathetic about voting in Canada, that’s where my mind went.

Her worldview was distinctly different. To her, a cisgender, heterosexual white woman, voting was more than a show of civic engagement; it was a duty. But for me, voting seemed more like an easy political act for the privileged that did very little to tip the scales of good and evil, and offered little material change to those most in need of it.

It’s easy to see voting as the political act when your identity doesn’t lie at the intersections of different marginal identities. Out of respect for all those who continue to be targeted and neglected by our flawed governmental system, voting is a part of my civic engagement. But, as I tried to explain to my friend in our conversations over weeks, for those of us like me, those of us who imagine a radical future, voting is not our number one priority. And it never will be.

Don't Miss Out

Subscribe to get our latest stories delivered to your inbox.

"*" indicates required fields

Post-Trump and Doug Ford, I don’t think I have ever seen so many of my fellow twentysomethings so engaged in politics. People posted “I Voted!” stickers on all their social platforms, shared Instagram slideshows on strategic voting, and tweeted about polling outcomes.

That enthusiasm has another side: the shame given out like candy every election season to those who don’t vote. Disappointment and rage are directed at non-voters—energy which could be better used focusing on why people don’t vote, and meeting them there.

“It feels like gaslighting,” says Ashleigh Rae Thomas, a writer, facilitator, and community organizer. Each election season, Thomas sees the same stern reminders: voting “is your civic duty. Your ancestors died for the right to vote. That if you don’t vote, you don’t have the right to complain about how things are.”

For Thomas, it’s insulting that white people and politicians feel comfortable asking Black and Indigenous folks to vote, especially to vote strategically, instead of “channelling that anger at politicians.”

“Every time I have to vote [it’s] like picking my next oppressor,” they say. Thomas remembers feeling frustrated by the arguments for Trudeau’s re-election in 2019. “You’re telling people to go and vote for this man who is trying to destroy [Indigenous peoples’] land further, and fighting survivors of residential schools in court? …That is madness. That is completely unfair.”

The push to vote “strategically” can feel particularly insidious. Instead of focusing on the politics of the running candidates, those who boost strategic voting argue that the best way to vote is not for the candidate that most aligns with your beliefs, but for the least evil, most “realistic” option. In this mindset, voting is no longer a personal act and instead a group project for which you will be judged if you haven’t “done your part.”

“When you don’t have to work and be amongst the communities that are suffering the most, it’s easy to fantasize about a candidate who will do the least amount of harm,” said Keeks Powell, a youth worker. “But the harm is still there.”

“One of the reasons that so many people fall back on [strategic voting] is because of the lack of alternatives in the electoral system,” says Larry Savage, a labour studies professor at Brock University. While it is hard for leftists to agree on what party or politician to back, it is far easier to decide to just vote for anyone who isn’t conservative. “They will tell you, ‘I don’t like voting strategically. But I feel like I have to because of the way our electoral system is set up.’ And I think they’re right to say that our electoral system does encourage strategic voting, especially when we’re in a political environment where people are more interested in voting against things than voting for things.”

For Talin Wright, a peer support worker, the way voting is pushed on Black folks feels like brainwashing. Wright first got politically involved after seeing the list of promises left unaddressed by the Liberal party, whose lack of engagement with the Black community also frustrated Wright. While the Liberals seemed to have a nice list of promises for Black Canadians, it was hard to have faith in them when their leader was caught doing blackface and MPs committed to focusing on core and not “woke” issues, which is usually code for putting the concerns of Black, Indigenous and other people of colour to the side.

Wright voted for the NDP and then the Green Party. But after years of researching Canadian voting patterns, the gaps in governmental COVID support, and voting inaccessibility, disillusionment with the electoral system as a whole set in. “If [I] thought voting would actually change something, then [I] would vote,” says Wright, “But to have gone through the system so many times and seen the lack of change? …It’s just not worth it.”

It’s the same for me. After years of voting and hoping that the government would make any sort of significant change—for housing, abolishing the police, truth and reconciliation, financial aid, accessibility for disabled folks, and more—those topics are still put on the back burner or worse, simply brushed aside.

“In a society like ours, elections are just about selecting which party is going to run the government, while everything else doesn’t change,” says David Camfield, one of the editors of the socialist magazine Midnight Sun. “We never vote for our bosses, we never vote for the people that run the university, we never vote for the people that run other major social institutions… If democracy really means control from below, by people over the decisions that affect their lives, then we live in a society that’s only very slightly democratic.”

For people like Wright, Powell, and Thomas, who are Black, queer, and/or trans, these flaws are enough reason to opt out of voting. Their community engagement comes in different forms— sharing meals for disabled and mentally ill friends, sharing mutual aid funds of friends and strangers alike, and finding alternative methods to keep vulnerable community members safe.

“We can’t fight our oppressors with the tools that they gave us,” says Powell, referencing Audre Lorde’s admonishment: The master’s tools will never dismantle the master’s house. “We are playing by their rules. … [Voting] does not dismantle these systems, it legitimizes [them].”

In this mindset, voting is no longer a personal act and instead a group project for which you will be judged if you haven’t “done your part.”

“Elections are one thing,” says Pam Frache, an organizer with Workers Action Centre and a coordinator for Justice For Workers. “But it’s only one tool and there’s all sorts of other ways that we can participate to make change, and ways that might even be more effective”.

“Just electing the right people isn’t enough,” says Denise Hammond, a union communicator and member of Toronto’s chapter of Showing Up for Racial Justice (SURJ), an organizing group of white folks allied with radical Black-led activism. “We still need to have that strong, grassroots movement outside, on the streets, being able to push them.”

“It can be easy to have a short-term take on [our current political state]… but if we’re in it for liberation, that’s a lifetime commitment,” says Camfield.

“We have to remember that the present is just one moment in history,” he said, “Things that today can seem to be unchangeable… may well certainly change. They’ve changed in the past and they will definitely change in the future.”

That sort of long-term look at change and political action is what helps comfort folks like Thomas and Wright, who look at the past to imagine a better future.

“I think about how Haiti gained its independence,” Thomas said. “How it was just regular people like enslaved people who rose up and fought off one of the most powerful nations in the world at the time… That’s incredible.”

That change can start small, with tiny acts of solidarity that snowball over time. When I think about the past few years of political engagement—the George Floyd protests, the pandemic mutual aid, the elections across all levels of government—I keep coming back to a small, seemingly insignificant moment at my old house.

Just before the pandemic, my roommates hosted a Purim celebration at our house. Growing up in a staunch Christian family, I had no clue what Purim was, but I made my way down to the main floor of my house. It was filled with people in various costumes, the living room packed with folks dancing and swaying along to the sounds of klezmer music played by a live band. In the kitchen, drinks, hamentashen, and other finger foods were available for purchase—with all proceeds going to Wet’suwet’en. This was before the wave of donations and mutual aid that coloured the summer of 2020. It warmed my heart to see a bunch of strangers—in and out of costumes, Jewish folks and allies—come together to support another community in crisis.

It’s hard to hold out hope that anything can change within the government—hard to fathom a western government that would put its people before pipelines, profits, or police. But those small moments of solidarity confirm to me that if voting doesn’t matter to me, then community-led actions always will.