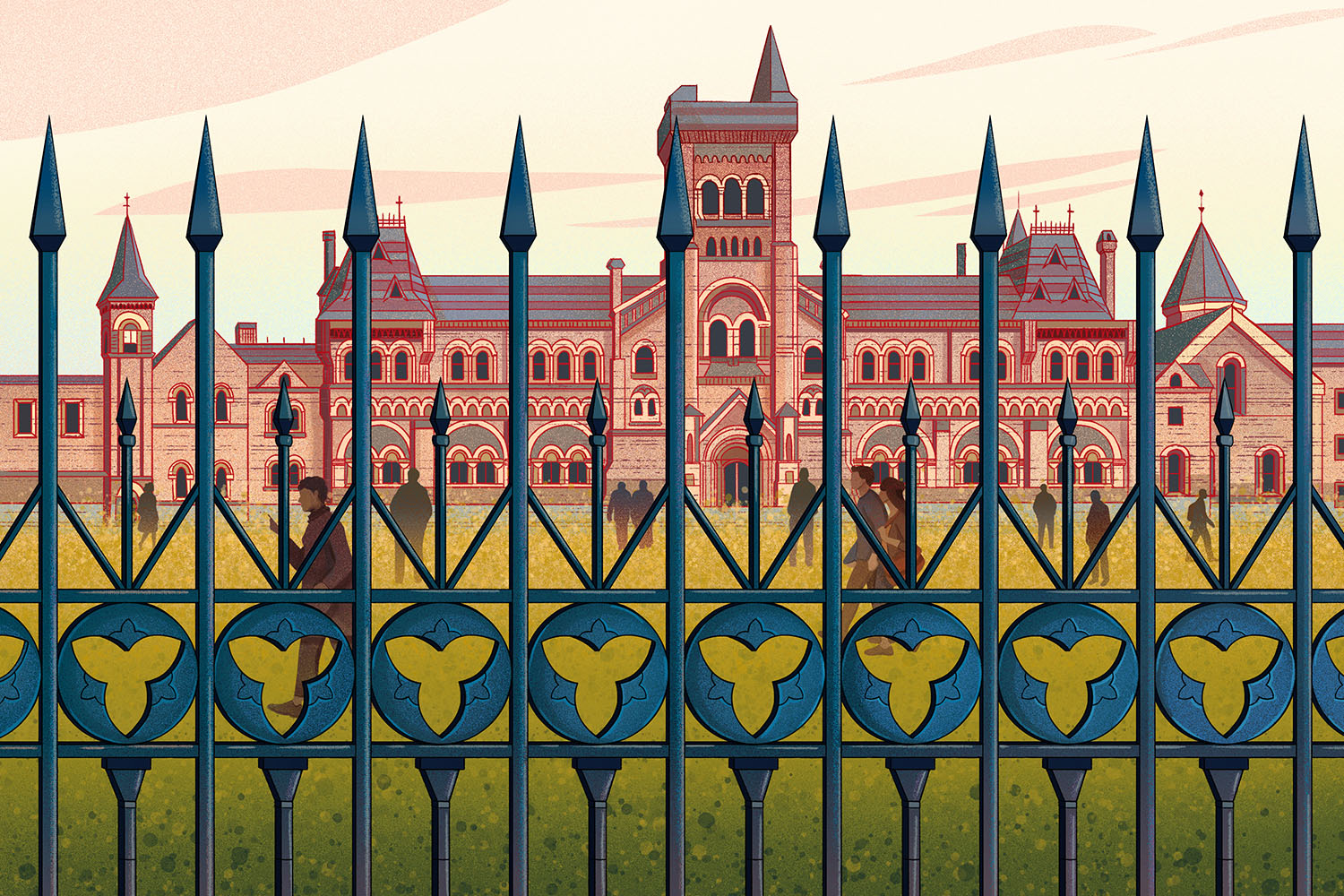

As students return to campus this fall, critics in the field of higher education are sounding the alarm over prospective Ontario legislation that could redefine the power the government has over university and college operations, and the well-being of their most marginalized attendees.

Under the post-secondary section of Bill 33, the Supporting Children and Students Act, the provincial government wants to grant itself the power to intervene in student admissions processes, mandating that applicants be considered “on the merit of the individual.” The bill would also allow the province to decide which ancillary fees—student costs and services that aren’t paid for by tuition or by university budgets—are mandatory and which are voluntary, something universities and student bodies have historically decided for themselves. Nolan Quinn, minister of colleges, universities, research excellence and security, describes the legislation as a measure in favour of transparency and saving students money.

Now in its second reading, Bill 33 is a sweeping legislative proposal that centralizes power in the hands of the province when it comes to primary and secondary education, colleges and universities, and child welfare services, all at once. While public outrage has largely been directed at the portion of the bill covering children’s education, the section on post-secondary institutions is vague enough that it grants the provincial government unprecedented leeway to dictate admission policies in higher education, and student fee management. Critics at every level—from student advocates to professors’ associations and labour unions, to university and college administrators—have warned that the bill is, at best, redundant red tape. And at worst, it’s a threat to the inclusion of marginalized or underrepresented students on campus, and to the rights of universities and colleges to govern themselves.

Join the thousands of Torontonians who've signed up for our free newsletter and get award-winning local journalism delivered to your inbox.

"*" indicates required fields

“This is probably one of the most egregious interventions in university autonomy we’ve ever seen in Canada,” says Glen Jones, a University of Toronto professor and scholar of governance in higher education. Historically, he explains, the province, as a funding source for public universities and colleges, has had the right to regulate financial matters like tuition fees and executive salaries. But the standard has always been to leave decisions like admission criteria, mental health policies, guardrails against hate or racism, and matters of campus life to the universities themselves. With Bill 33’s infringement into admissions and ancillary fees, “any government from this point on, regardless of their ideological foundations, will have the right to intervene in these particular areas—and not just intervene, but essentially tell universities what to do and punish them if they don’t,” says Jones.

There’s no precedent for the provincial government stepping in like this at an institutional level. With the vague language of the bill, it’s unclear what enforcement of these policies or penalties would even look like. The Local reached out to every major college and university in Toronto for comment, and none were able to weigh in.

What we know is that in its current form, Bill 33 paves the way for the provincial government to intervene if they don’t like a university’s admissions policy. Admission to an Ontario undergraduate program today is based primarily on grades; depending on what program a student is hoping to enter, they may have to additionally submit information about their extracurriculars, prior experience, or samples of their work. For some programs, like performing arts, they may have to audition. If the student is from a community that is underrepresented in academia—for most institutions, this includes Indigenous, disabled, or mature students, or youth in care—most universities have pathways to make higher education more accessible to them. And if a student has extenuating circumstances that affect their grades, they can inform the schools they’re applying to.

Under Bill 33, if the provincial government felt any of these pathways to access higher education were inappropriate, or didn’t meet their definition of merit—which they haven’t defined in the proposed legislation but may do so through regulations—or if they felt that it was unfair for marginalized students to be given particular consideration, they could regulate the practice out of existence. This could look like eliminating the Indigenous admissions pathway most universities provide, or barring questions about demographics or identity from any supplemental applications.

“This is probably one of the most egregious interventions in university autonomy we’ve ever seen in Canada.”

All of the experts and student and faculty organizations that The Local spoke with for this story described concerns about the language of “merit-based” admissions. “On what basis are we deciding that merit, and how are we measuring it?” says Carl Everton James, chair in education, community and diaspora at York University. When two applicants vie for the same spot with different grades and social circumstances, and with unequal access to resources, “we have to pay attention to the social, political, economic and cultural context,” James says. The student’s performance within their given institution and environment is part of what determines their merit. “Why would you say, now, that merit is not accounting for the kinds of students we’re seeing getting into university?”

In 2023, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled to end affirmative action policies at Harvard and the University of North Carolina, setting a precedent that has jeapordized access to education for underrepresented students, especially Black students, across the country. Earlier this year, when U.S. Attorney General Pam Bondi announced an investigation of universities suspected of not complying with the affirmative action ban, she used familiar language: “President Trump and I are dedicated to ending illegal discrimination and restoring merit-based opportunity across the country.”

The Ford government has not explicitly stated that they intend to do away with diversity, equity, and inclusion policies in higher education. But the language, critics point out, seems to insinuate that students admitted to university or college right now are being admitted on something other than merit—like identity, a common right-wing talking point. In the National Post, columnist and former Conservative provincial candidate Randall Denley praised the bill, writing, “Ford and his team are not selling their new Bill 33 as an attack on DEI, but that’s clearly what it is. Universities and colleges will be obliged to admit students on merit, rather than their membership in a targeted demographic. That should stem their ability to impose reverse discrimination to over-correct for perceived past injustices.”

Another mandate in the post-secondary section of the bill relates to research, stating that academic institutions should “develop and implement a research security plan” safeguarding its research activities—a measure critics say is redundant overreach. The federal government already has robust legislation on the protection of Canadian research interests and practices, and anything the province demands would be redundant or just add more red tape—something Ford has built his reputation on fighting.

Colleges and universities minister Nolan Quinn declined to answer The Local’s questions, but spokesperson Bianca Giacoboni said in a statement that students “deserve to know where their fees are going, what criteria they need for admission and how their research will be protected. If passed, this bill would ensure transparency and foster better trust in our post-secondary education system.”

The other major part of the higher education portion of the bill covers ancillary fees, the lifeblood of organizations like students’ unions, mental health resources, sexual violence support services, food banks, and campus newspapers, among others.

Bill 33 isn’t the first time the Ford government has tried to go after ancillary fees in post-secondary schools. In January 2019, the province introduced the Student Choice Initiative, a policy that allowed students to opt out of paying into campus services deemed non-essential by the provincial government. When the Canadian Federation of Students and the York Federation of Students challenged the initiative in court just months later, supported by the University of Toronto Graduate Students’ Union, they pointed out the discrepancy in Ford’s rationale for the policy. Publicly, the provincial government had cited an interest in cutting costs for students. But in a party fundraising email, Ford wrote: “I think we all know what kind of crazy Marxist nonsense student unions get up to. So, we fixed that. Student union fees are now opt-in.”

The Student Choice Initiative was struck down later that year by an Ontario court, which ruled that the initiative violated universities’ rights to autonomy. This didn’t mean, however, that the Ford government couldn’t propose a version of this policy as a bill.

Six years later, the Ford government once again says it wants to cut costs through potentially eliminating the fees. In the time since the Student Choice Initiative, reliance on the services funded by ancillary fees has only deepened. Today, one in every three food bank users in Toronto is a student. Demand for mental health services on campus has been growing for more than a decade. Rising unemployment rates mean additional visits to campus employment services.

Local Journalism Matters.

We're able to produce impactful, award-winning journalism thanks to the generous support of readers. By supporting The Local, you're contributing to a new kind of journalism—in-depth, non-profit, from corners of Toronto too often overlooked.

Support“These ancillary fees are providing life-saving services to fill in large and very intentional gaps on our campuses that government institutions continue to leave,” says Omar Mousa, national executive representative for the Canadian Federation of Students’ Ontario chapter.

Beyond potentially leaving vital services unfunded, critics say the move to control ancillary fees is another attempt by the government to insert itself into campus politics. If the provincial government were to disapprove of the actions of any one of the campus organizations supported by ancillary fees—like a student union’s vote in favour of a particular political movement, or a protest organized by a student group funded through ancillary fees—Bill 33 gives them the power to unilaterally mandate that students can opt out of paying for groups of that nature, thus jeopardizing their existence.

“Having assumed this authority, how will a government use it?” Jones asks.

It’s difficult not to see Bill 33 as Ontario’s iteration of a broader right-wing crackdown on campus politics. The last decade of student activism—from protests for trans rights and racial justice to the establishment of student encampments in support of Palestine—has triggered a wave of conservative backlash not only in Ontario, but across Canada and the U.S. Now, that backlash is being enshrined in policy. In the U.S., the Trump administration has threatened to withhold billions of dollars in funding from major universities over their handling of pro-Palestine protests and trans rights, although a federal judge ruled that Trump’s actions were unlawful just last week. In Alberta, the provincial government passed the Provincial Priorities Act in spring 2024, which mandated all provincial institutions, including universities, seek approval from the provincial government before signing funding agreements with the federal government. At the time, Alberta Premier Danielle Smith justified the act as a response to what she alleged were progressive biases shared by the academic sector and the federal government; it was only after a year of advocacy that the post-secondary sector was able to secure amendments to the act that restored their access to federal funding.

“I don’t think there’s any doubt that events in the United States have had an impact [on the bill],” says Jones. “I think that the province has created pathways with the notion that it may want to get involved with these politically sensitive issues, even though, historically, they’ve left them in the hands of the university.…It’s really about reducing the independence of universities.”

Almost everyone The Local interviewed for this story described Bill 33 and the discussion around merit-based admissions and politics on campus as a distraction from the chronic underfunding of Ontario’s post-secondary institutions by the province. Ontario remains the province with the lowest rate of funding per student for public post-secondary education in Canada. And over the next 20 years, the province’s universities and colleges will need funding for an expected 225,000 students in order to keep up with demand from the next generation of post-secondary attendees.

“Universities are operating with 2025 costs, but with revenues at the level of 2015,” says Rob Kristofferson, a Wilfrid Laurier professor and president of the Ontario Confederation of University Faculty Associations. “As a professor who loves the university, has devoted my life to the university, the last number of years have just been really disheartening in seeing so much opportunity, so much more we could do for our students, but being held back because of inadequate funding.”

Instead of discussing more funding, when parliament is back in session in October, the debate around Bill 33 will resume. Since June, groups representing students, faculty, and administrators have been submitting responses to the bill—every single one The Local was able to access criticizes the proposed legislation, from raising serious concerns about its implementation to condemning it outright.

It’s now up to the province whether or not they’ll take these stakeholder recommendations into account and make amendments to the bill. Giacoboni, the spokesperson for Minister Nolan Quinn, told The Local in a statement that the province “will be consulting with the sector to understand what fees could or should be optional, what current admissions policies look like, and what research security practices can be enhanced in a way that does not disrupt the delivery of a world class education. No regulations will come until consultation has concluded.” But MPP Peggy Sattler, the opposition critic for colleges and universities, warns that in this most recent legislative session, the Conservatives frequently eliminated the opportunity for public, on-the-record consultation and amendment of proposed bills. So despite the numerous submissions that have been made against the bill, it’s unclear whether students and faculty organizations will have the opportunity to publicly debate the bill, or whether it’ll be rushed through Parliament. “They’ve really shown that they are prepared to ram through legislation as quickly as possible,” Sattler says, “with as little public input as possible.”