In the summer of 2020—the summer before I left my job, uprooted my life, and moved to Toronto to become a midwife—three heat waves struck Montreal, sending temperatures into the 40s with humidity and breaking city records.

I worked in an old wing of a large hospital then, caring mostly for elderly people with nowhere else to go. For weeks I lay sleepless in bed, trying to rest before night shifts in my airless apartment—one of those old Montreal buildings with strange dimensions and slanted floors, where anything that fell to the ground rolled its way to the kitchen.

I would work from 7:30 in the evening to 7:30 the next morning, then rest through the torpid afternoon, trying to prepare mentally and physically for the next shift. The midday sun basted the apartment, melting the tar on our roof and sending it dripping through the ceiling as I lay for hours on the suffocating mattress.

In the hospital, I cared for elderly people with heat stroke and delirium. One woman had lain on the floor for days, too weak to get up, and was only found by the police after a neighbour complained about the smell in her apartment. She lay in the hospital for several days, never regaining clarity, and died alone, succumbing to organ failure caused by severe dehydration, one of 14 people to die in that year’s heat wave.

At that point I had already decided to leave nursing, putting aside my worries that leaving a profession that so clearly needed me was a sign of weakness. I needed a change. And I’d thought about birth and midwifery for a long time.

I’d seen my first birth in nursing school years earlier. The baby had come into the world in a quick jumble of limbs, glistening with blood and wax and amniotic fluid, his head long and conical from his journey through the birth canal. I loved seeing how our messy bodies could be so full of life. The world gives you so many reasons to despair; as I nurse, I’d seen how much our bodies can suffer. But for a moment, all of that is forgotten as you hear new life take its first breaths and cry out. I knew I wanted to witness births again and again.

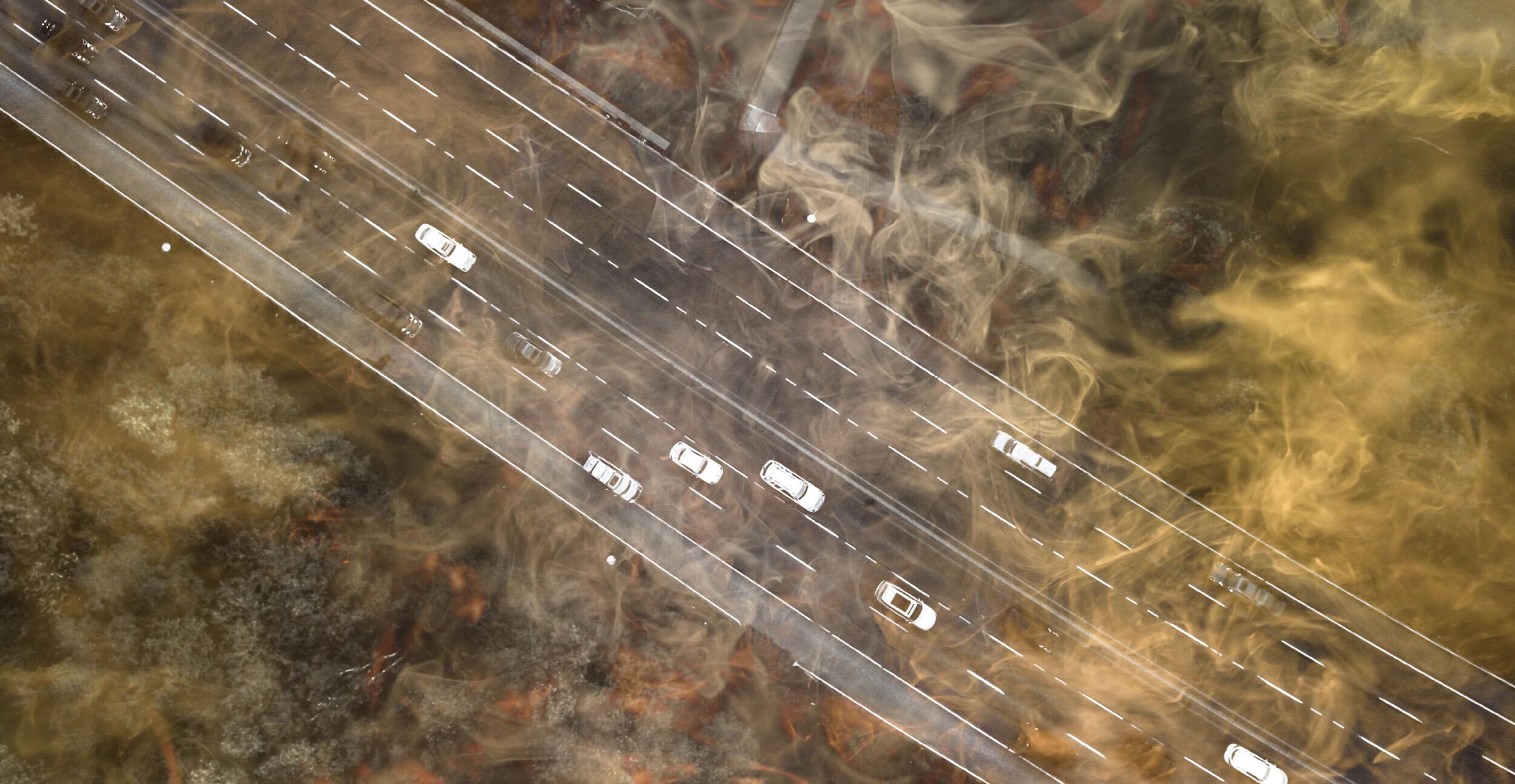

At the same time, I’ve grown increasingly aware of the perils of the world we’re bringing babies into. And the most existential threat to human beings—the one that ties together all of my worries, the one we see more and more evidence of every year—is the climate crisis.

A child born today will witness a world where a projected 300 million people lose their homes to coastal flooding and rising sea levels. The rate of natural disasters will increase fourfold. Droughts will result in billions of people experiencing chronic water scarcity and lack of access to food.

More than ever, it feels like birth workers need to have a special weight to their character: the ability to advocate for expectant parents, to provide safety, comfort, and a sense of hope to them when every day presents a million things that would make them feel otherwise. What does it take to help bring life into a world that feels increasingly hostile towards it?

Don't miss out

Subscribe today to get our latest stories delivered to your inbox.

"*" indicates required fields

Year after year, the United Nations’ Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change has released reports warning that business as usual will kill off many of the earth’s species and leave the rest to suffer. The latest report warns that we are “firmly on track toward an unlivable world”: current rates of greenhouse gas emissions will lead to increasingly catastrophic natural disasters and untenable global temperature rise.

I am 25 years old, and have been warned about the climate crisis since I was a child. In that time, the politicians responsible for my future have broken every promise made to protect me, choosing to instead prioritize profit and the interests of business executives. I have a gripping fear of the future that is unfolding, and grief and anger knowing this world was already apocalyptic for many, especially Black, brown, and Indigenous people. Kyle Powys Whyte, a climate justice scholar from the Potawatomi Nation, wrote in a 2018 article in Yes! Magazine: “For many Indigenous peoples in North America, we are already living in what our ancestors would have understood as dystopian or post-apocalyptic times. In a cataclysmically short period, the capitalist–colonialist partnership has destroyed our relationships with thousands of species and ecosystems.”

As midwives, we work as primary caregivers for pregnant and birthing people. We are highly trained specialists in low-risk, normal birth. We acknowledge that birth has important spiritual and cultural dimensions, and try to honour them in the work we do. As a non-Indigenous student, I have learned about the rich traditions of Indigenous midwifery in North America, and bringing birth home is part of healing the wounds of colonialism.

But what will it mean to bring birth home as sea levels rise? As orcas are killed by oil tankers, birds die in the heat, and the forests burn? Is this the kind of world anyone wants to birth a child in?

Friends my age express a fear of having children because of what the future holds. The birth rate in Canada has been declining steadily over the last five years, and in 2021, reached a 15-year low. Jobs are untenable, housing is unaffordable, and parents have few supports in the massive work of nurturing a child. It’s hard to deny the further horror of an unlivable world.

For a moment, all of that is forgotten as you hear new life take its first breaths and cry out. I knew I wanted to witness births again and again.

Last September, my boyfriend and I packed up a U-Haul with the contents of our Montreal apartments and moved to Toronto. I felt immediately welcome in this city, with its slinky red streetcars and clouds rolling off the lake. My new home in the Annex was a short bike ride from Toronto Metropolitan University, where I was to spend the next four years learning to be a midwife. The first time I visited our faculty, it made me smile to see that the student lounge had been decorated with banners saying ‘Midwives for Peace’ and ‘Water is Life’.

It may feel like the climate crisis, or social justice more broadly, is unrelated to midwifery. But the factors people have to consider in choosing to have and raise children, and their experiences of doing so, are all deeply linked to equity. In 2020, a study looking at more than 32 million births in the United States found that the climate crisis had detrimental effects on pregnancy outcomes. Higher temperatures and air pollution were found to increase the risk of babies being born premature, low-weight, or stillborn, and Black mothers, who are disproportionately exposed to pollution and urban heat island effect, are at the greatest risk.

Closer to home, in Grassy Narrows First Nation in northwestern Ontario, generation after generation have felt the devastating health effects of mercury poisoning caused by a nearby paper mill polluting the local river in the 1960s and 70s. Mercury poisoning is most dangerous to young children, and among other effects, can damage people’s reproductive capacities. It is passed down from parent to child.

As midwives, our Black and Indigenous clients are already more likely to have limited reproductive care, be subject to forced sterilization, and face complications during childbirth than other clients. As the climate crisis poses threats to babies’ health, increases the risks of gendered violence, and further burdens the health care system, these disparities will only get worse.

I know that thinking about the climate crisis can be terrifying and discouraging. But if anything makes hope possible, it’s midwifery’s tradition of solidarity and collective action. We study and fight for social justice because we know that people have the right to clean air as much as they have the right to receive respectful prenatal care. Every week, I organize with a group of young climate justice activists, fighting for free transit, affordable housing, and green jobs.

What will it mean to bring birth home as sea levels rise? As orcas are killed by oil tankers, birds die in the heat, and the forests burn?

This June, just after the solstice, I helped deliver a baby for the first time. It was during my first shift in the labour and delivery unit, on a day when a “heat event” sent the temperature into the mid-thirties. I felt my patient’s stomach early in her labour, tracing the outline of the baby’s head and back. I pressed the heart monitor to her skin filling the room with the rapid, steady sound of the baby’s healthy heart. We talked a little throughout the labour, about the baby’s sisters waiting impatiently at home, the wicked heat. I brought her soda crackers and ice. I watched the anesthesiologist put in an epidural, the long plastic catheter unspooling down the patient’s spine.

After a few hours, she described feeling a sudden heavy weight around her hips. The room filled with nurses and doctors, and very quickly she began to push. As I watched from the back of the room, I began to laugh, not because it was funny, but out of joy. For an instant, seeing a new life emerge where a moment ago there was nothing, made everything feel possible. As the doctors cooed at the baby and brought him to his mother, I wished I could give him that feeling forever.

At home that evening, I peeled off my sweaty socks and filled the large pot I use to water my balcony garden. The heat had made the mint plants droop and wilted the tomatoes. I wondered how long it would last, whether the plants would make it, whether our taps would always run water. I thought about the baby I had just watched being born, what life would be like for him. I felt ferocious care and ferocious worry, and though this child is not mine, I knew that I would always fight to create the kind of world I want our children to inherit.