On the first sunny day in May, I take a Tiki-themed water taxi to the Toronto Islands to see the double-crested cormorant in action. This was necessary, I was told, to understand the antipathy towards these creatures—dinosaur-era colonial waterbirds that are hated and slaughtered wherever they go. Unlike more beloved bird species, like swans and ducks, when cormorants gather in large colonies, they drastically alter the landscape. In the right conditions, their nitrogen-rich guano suffocates the trees they nest in and all vegetation below. Their unique body shape—streamlined, propulsive, and little changed since the dawn of their species 66 million to 22 million years ago—means they’re highly efficient predators of aquatic prey, drawing the ire of sport and commercial fishers. All this has made the cormorant the most divisive, politicized, and persecuted bird on earth.

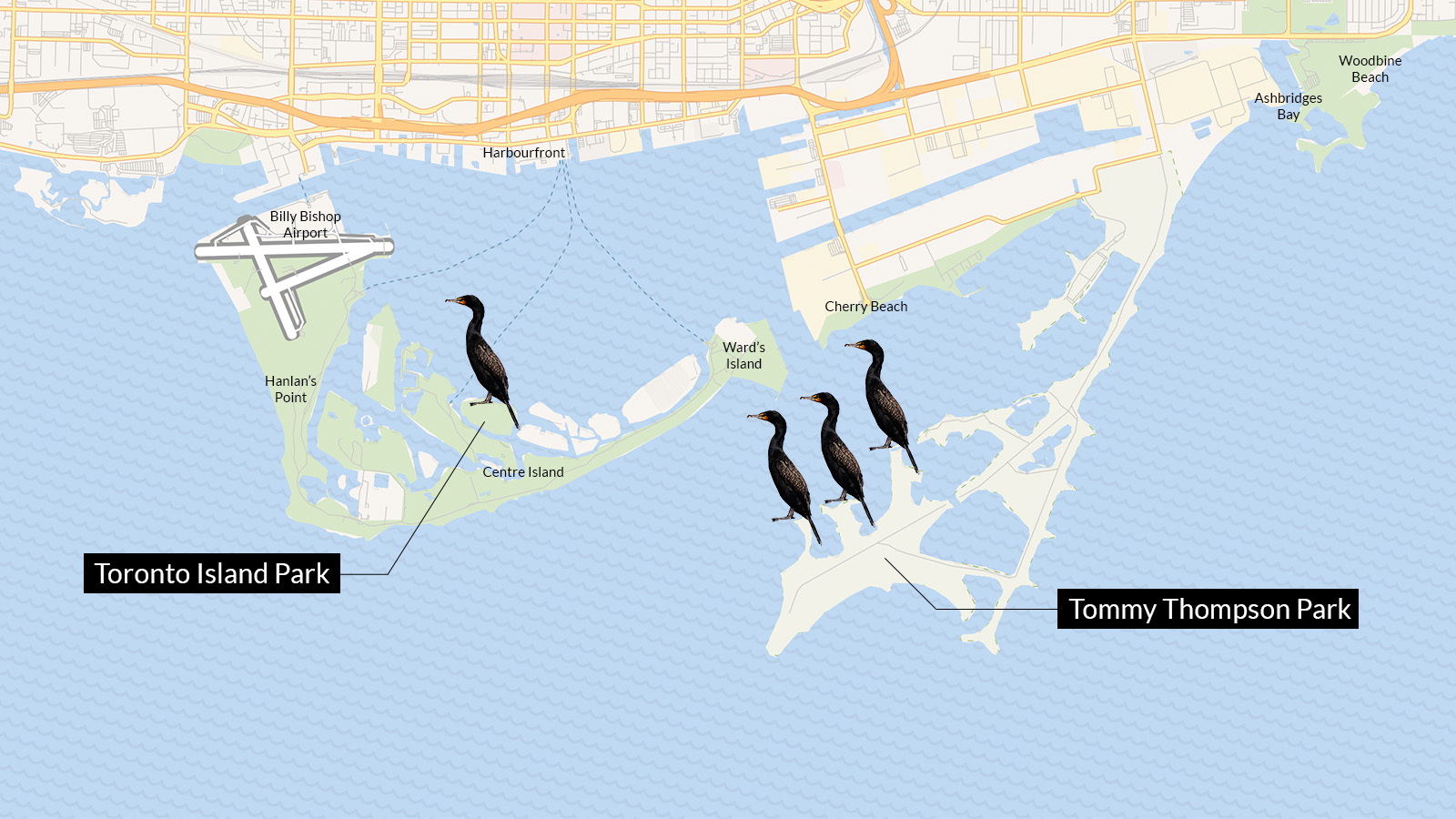

Toronto is home to the largest double-crested cormorant colony in North America, in a sanctuary area in Tommy Thompson Park on the Leslie Street Spit. In recent years, however, the birds have moved from their nesting area on the Spit to parts of the Toronto Islands. Residents have expressed concern they could spread further across the Toronto Islands, High Park, and the Humber River marshlands, tightening their hold on the city’s waterfront.

As we near Hanlan’s Point, cormorants collect around the tips of trees, circle the sky in groups, and skid the lake’s surface to retrieve sticks and strips of floating plastic for their nests. Up close, the birds have goofy faces, long goose-like necks, and bright green eyes that look like faceted sequins. They seem to be part snake, their bodies liquifying as they dive beneath the water. One catches a small silver fish, swallows it, and then regurgitates it whole and (I think) alive. Occasionally, after a dive, they do the thing they’re most famous for, which is hang in the air or on a perch for a few seconds with their heads turned to the side and their serrated wings outstretched. This dramatic move has a biological purpose, directing UV rays at their bellies to turbo-dry their non-waterproof feathers. Its non-biological purpose is to make them look glam rock and cool. It makes me think of the Buffalo Bill robe-reveal moment in The Silence of the Lambs. It’s an intense, but ultimately brief experience.

Unsurprisingly given their goth appearance, cormorants appear frequently throughout Western art as symbols of ungovernable nature. Milton imagined them as stand-ins for Satan, Shakespeare as metaphors for greed. Toronto’s cormorant war repeats this historic theme. The birds here are the subject of incendiary debate: between the fishers, hunters, boaters, and property owners who want to kill them, the scientists and wildlife conservationists who lobby for their protection, and government actors eager to develop the waterfront, now branded as “biodiverse,” without the complication of a massive colony of puking black birds. Cormorants are more than birds to us. They’re vectors for clashing ideas about cities, wildlife, and how humans co-exist—or don’t—with the aspects of nature that remain especially messy, visible, and resistant to our control.

Fossil evidence suggests that double-crested cormorants have always been in the Great Lakes region, just in much smaller numbers. The birds began appearing in larger numbers in the late 19th to early 20th century, as part of an eastward expansion, bringing them into immediate conflict with growing commercial fisheries as well as colonial developers. Across Ontario, cormorant populations were reduced with regular culls, which occurred until the 1940s. By the 1950s, they were pretty much all gone, the combined result of culling, the effects of DDT toxins, and downstream effects from overfishing and development.

A reversal began in the 1970s, as regulations on DDT caused contaminant levels to fall, and the Great Lakes became home to abundant new species of prey fish. From 1973 to 1991, cormorant numbers increased more than 300-fold. In Toronto, cormorants’ recovery was also the result of changes to the Leslie Street Spit, a peninsula created entirely out of construction landfill for use as a shipping port and related infrastructure in the 1950s before being largely abandoned by the 1970s, its surface rewilding into marshland.

Under the influence of local environmental conservation groups, the city divided the land between the Port Authority and the Toronto and Region Conservation Authority, which was tasked with developing the former dumping ground into a public park focused on conservation and nature education. The result, Tommy Thompson Park (TTP), is a series of aquatic parks and cottonwood forests strung together by recreational trails that contain some of the most diverse and ecologically sensitive species in Canada. By the 1990s, it had exactly the right conditions for a large colony of cormorants: a contaminant-free ecosystem, a relatively undisturbed nesting area, water full of prey fish, and—importantly—a habitat protected by modern conservation principles. In 1990, there were six cormorant nests at Tommy Thompson Park; by 2007 there were 4,699.

Throughout Ontario, as the number of cormorants grew, so did anti-cormorant sentiment, with lobby groups pressing the government for population management. By now, however, expert consensus had shifted against lethal culling without a clear scientific argument for its necessity. In 2007, in consultation with government biologists, First Nations, and the public, Parks Canada began developing a management plan for areas within its jurisdiction with large cormorant colonies, like Middle Island and Point Pelee National Park off Lake Erie. “Hyperabundant double-crested cormorants nesting on Middle Island are a serious threat to the island’s fragile Carolinian ecosystem and the species at risk located there,” Julia Grcevic, a spokesperson for Parks Canada, told The Local in an emailed statement. Active management began in 2008, with culling sessions scheduled every year over a period of two or three weeks in an uninhabited island off-limits to the public.

The results have been dramatic. From 7,516 birds in 2010, Middle Island had 4,478 birds during the latest count in 2024. Since 2007, the island has seen a 25.5 percent increase in canopy cover, a reduction in the rate of tree loss, and the recovery of federally-designated species at risk, such as wild hyacinth and the Eastern Banded Tigersnail, that had gone into decline from cormorant nesting impacts. The culls, Parks Canada says, “are resulting in real conservation gains.”

Many conservationists see them in a different light. “Culling is the Final Solution school of wildlife management,” says artist and activist Barry MacKay, a founding director of Animal Alliance of Canada, which has fought for years to end the cull. When I meet him at his home in Markham in mid-April, MacKay is preparing to go out to observe the annual cull on Lake Erie. Animal Alliance won the right to monitor Parks’ Canada’s culling activities in 2008 to ensure activities adhere to the Environmental Assessment Act, and MacKay has witnessed over a dozen culls since. “Cormorants are devoted parents—they’re so devoted to their young they don’t leave their nests,” he says. The reason their colonies are so dense is the same reason Parks Canada can shoot them so easily by the thousand. “Parks Canada takes advantage of that, sending out snipers in teams to shoot them out of their nests with a .117 rifle. Some are wounded and get away. They then hunt those down with a boat and shoot them with a shotgun.”

The Ontario Federation of Anglers and Hunters (OFAH) has been one of the largest and most vocal groups lobbying for lethal cormorant management in areas that fall under provincial jurisdiction. Their argument, developed by their own biologists and repeated in much media coverage, is that cormorants pose a significant threat to native forest species and wildlife and fisheries, which justifies controlling them by lethal measures. Cormorant culling is in line with conservation principles, they argue, because cormorants are both invasive and overabundant in the Great Lakes ecosystem.

Matthew Robbins, a fish and wildlife biologist with the OFAH, tells me that cormorants were native to the Lake of the Woods area, but not the areas of Ontario they occupy now. “Humans see things in black and white terms,” he says. “Just because something is native, doesn’t mean it’s good.”

Their abundance is inarguable, with recent research proving cormorants’ damaging impact on their nesting areas as well as on commercially valued fish like yellow perch and bass, says Robbins. But there are no universal management solutions, because cormorants cause huge issues in one area and few in another (for example, in Lake Ontario, their diet is largely the commercially worthless alewife and round gobi). Hunting is not the ideal, or only solution, Robbins says. Other strategies include oiling eggs, relocating nests, and encouraging nesting for competitor species. And he doesn’t believe we have to get rid of all cormorants. “But it does mean we have to take a management approach.”

In July 2020, with both cormorants and pressure from lobby groups at an all-time high, the Ontario government announced it would be lifting a historic hunting ban, allowing recreational hunters to kill up to 50 cormorants a day between September and December (a number that was reduced to 15 after much outcry). It was an unusual plan that essentially recruited recreational hunters into a war against cormorants that had, until then, been done “professionally”, with government marksmen, statistics, and the legitimizing veneer of bureaucracy. (The Ministry of Natural Resources did not respond to questions about the hunting legislation by the time of publication.)

The next day, an open letter by 51 scientists responded to the announcement. Initiated by Gail Fraser, professor in the faculty of environmental and urban change at York University, who runs a year-round monitoring station in Tommy Thompson Park, the letter rebutted the government’s arguments point-by-point. There was no good evidence that cormorants were depleting commercial and sport fish, the letter said. Tree and vegetation loss was irritating but ultimately limited in scope. And exterminating large numbers of a predator species could have dangerous effects on the entire ecosystem.

Fraser, along with many other scientists and conservationists, has been outspoken about what she says is misinformation in the government’s and OFAH’s account. Aside from its xenophobic ring, the government’s “invasive species” language plays into the public’s ignorance about how healthy ecosystems are dynamic and adaptable to new and returning species. “There’s a whole generation of people who didn’t see cormorants,” she says. “They’d been almost completely extirpated from the local ecosystems. So then when they returned, it looked like they were an invasive species. But really, they were just coming back.”

Fraser says lobby groups misrepresent existing independent research and undertake their own studies to support their preferred policy positions. Beyond that, research and media that state there are too many cormorants are dangerous not only because they misrepresent the ecological science, but because of the human-centered worldview they sustain, says Fraser. “People think they have ownership of ecosystems,” she explains. If they’re fishing for yellow perch, they expect to catch it, without competition from some bird. “They are ecologically illiterate.” Government and lobby groups arguing for killing cormorants stoke a sentiment in the public that has brought us to an ecological crisis: the idea that ecosystems and species are static, separate from human communities, and ideally under our control.

Join the thousands of Torontonians who've signed up for our free newsletter and get award-winning local journalism delivered to your inbox.

"*" indicates required fields

Still, the cull continues. And since 2020, recreational hunters across Ontario have been making good on their end of the Ford government’s bargain. The Ministry of Natural Resources and Forestry reported 961 cormorant hunters the first year.

For opponents, the 2020 hunting legislation is, in many ways, just another iteration of violent culling practices that have targeted Great Lakes cormorants since the 1800s. The twist is that—unlike politicians and lobbyists—the motivations of the hunters are plain to see. In a Facebook group called Ontario Cormorant Hunters, created a month after Ford’s policy went into effect and which now contains 1,300 people, members organize shooting tours, trade hunting strategies, and post photos of kills: piles of carcasses in the back of pickup trucks, on grounds in nesting areas and the bows of boats, often accompanied by the shooter, grinning. There’s a hashtag—#FlightCancelled—and plenty of comments like “kill em all” and “smash the hell out of them” and “what’s the limit on these dirty fuckers?” These guys are “on the same continuum” as the government managers, Animal Alliance’s Barry MacKay says. “They want to kill.”

While the cull and the province’s hunting legislation have put cormorant colonies across Ontario in peril, there’s one place they can thrive: Toronto.

Here, cormorants remained unshootable under both local firearm bylaws and the Toronto and Region Conservation Authority’s (TRCA’s) own non-violent management strategy. By the mid-2000s, Toronto’s Leslie Street Spit had the largest cormorant colony in North America.

“The spit and TTP is a really unique situation,” says Karen McDonald, senior manager of ecosystem management at TRCA. “It’s a completely human constructed landmass that was never intended to be a park, and colonial waterbirds were among the first species to use it. They’re one of the reasons why it’s been designated as a globally significant biodiversity area.”

As manager, it is McDonald’s job to oversee the flourishing of all species in the ecosystem. That means finding ways to limit their impact on trees and vegetation with non-violent solutions. From April to early June, while the birds are still overwintering in Mexico, McDonald’s team is out on the waterfront, counting nests, moving them from trees to the ground with forestry poles and ropes, and encouraging nesting for cormorant competitors like black-crowned night herons and common terns.

But this ecosystem, like all ecosystems, is difficult to predict. “In 2023 we were able to reduce their nests by about 45 percent, but wound up dispersing them over a larger area,” McDonald explains. Then in 2024, a pair of bald eagles—the first in living memory—moved into a nest on Centre Island, in the middle of a cormorant colony. The eagles were a welcome surprise, “an excellent indicator of biological health,” says McDonald. But they complicated the cormorant mitigation strategy. Bald eagles are a protected species, so the TRCA established a 100-meter no-go buffer around their nest, halting their cormorant management work. Eagles and cormorants are competitors, but the TRCA left the outcome to the birds themselves. “We had heard examples of where cormorants had pushed the bald eagles out of the area. So we really didn’t know what was going to happen,” says McDonald. “And there were a couple of nervous points in the season where we saw footage of cormorants actually going after the bald eagle chicks.” In the end, the no-go buffer worked and the eagles successfully raised two eaglets.

But cormorants are smart, and long after the eaglets fledged, they continued to build nests only in the 100-meter buffer zone. Rather than retreating, the cormorants on the Islands have only increased. “It’s a good example of the challenges of wildlife management,” McDonald tells me. Animals don’t always do what you want them to do.

I see no cormorants when I visit Harbourfront later in May, though everyone I talk to is eager to discuss them. Taylor Brown, dockmaster at Marina Quay West and a frequent camper on the Islands, tells me that while the people who live and work on the waterfront and on the Islands are sympathetic to the birds, they suffer their impacts most directly. “I’ve watched over the past three years as the cormorants slowly have come closer and closer to the island and destroy the trees that they’re nesting on, and there’s thousands of them,” he says. “You can actually smell them from the harbourfront now, the smell of their droppings are so strong. I see all these old trees, some of them are a hundred years old. It would take a lifetime, definitely my lifetime, to see those trees come back.”

Brown, like everyone I speak to on the waterfront, is critical of media coverage of the issue, which has generally been pro-cormorant. “Everyone tries to label this a boater issue,” he says, because it suggests the primary opponents of cormorants are wealthy people, who can always sail elsewhere. “But it’s not just rich people down here, it’s lots of low-income people, people live here, we work here.”

Hector, one of several seniors I meet who lives on a docked boat in Marina Quay West, tells me that the constant smell and noise have become intolerable. “Get rid of them all,” he says directly. “Or hell, send them down to Florida, let them kill some palm trees instead.” Two workers on a restaurant boat, a water taxi driver, a teenaged girl selling Nestle Drumsticks Originals from a wheelie-cart, and a patio bartender also tell me that the smell from the Islands is difficult to endure.

I try to describe the scientific consensus to the girl selling ice cream. Cormorants are not a significant threat to fish, trees, or human endeavour. I talk about modern wildlife ethics, in which cormorants and humans are two of zillions of species, living in a fluid state of constant co-creation, as entitled as we are to a peaceful existence. In the era of climate disaster and biodiversity loss, I say, the mandate is clear: we must co-exist. She smiles. That’s probably how I’d feel too if I were you, her expression seems to suggest. You don’t have to sell Nestle Drumsticks Originals for eight hours in the blazing sun downwind of huge deposits of cormorant guano.

I want to go on, but I’ve been researching these animals for over a month and have lost my objectivity. It’s not that the people who dislike the birds are wrong, it’s that there’s more. I’ve fallen in love with cormorants, and their black wings beat in my heart day and night.

This is not unexpected. As I’ve discovered, as many people as there are who really hate cormorants, there are also people who really, really love them: their intelligence, their resilience, their dark romance. There are hundreds of fiction and non-fiction books, at least a couple dozen bands, and hundreds of songs about cormorants, most of which range from admiring to rapturous. Cormorant Defenders International, an umbrella group for conservation groups worldwide, has 15,000,000 members. I suspect, but don’t know for sure, that this is something that happens to people who wind up observing cormorants a lot, especially up close.

Toronto artist Cole Swanson, who has produced a vast body of acclaimed art about cormorants across multiple disciplines, points out that my feelings are in line with a larger cultural shift in the narrative around the birds. While previous generations associated cormorants with gluttony and evil, contemporary artists have become attuned to cormorants’ admirable, tender, and even subversive qualities, as well as the ways in which we find common cause. Black American poet J. Drew Lanham has written extensively about how the Western persecution of cormorants—still referred to colloquially as an “n-word goose” in parts of the U.S.—has expressed and fuelled anti-Black sentiment and policy. Becoming attuned to cormorants’ history of persecution can be an opportunity to “think, learn and act in solidarity” with not only these animals, but the many other outcast, demonized, and slaughtered populations they have come to represent. “Cormorants are resisters,” he says, citing a 2013 event in Seattle in which a group of cull survivors re-nested on the Columbia River Bridge and were eventually shot down by U.S. Armed Forces.

Local Journalism Matters.

We're able to produce impactful, award-winning journalism thanks to the generous support of readers. By supporting The Local, you're contributing to a new kind of journalism—in-depth, non-profit, from corners of Toronto too often overlooked.

SupportIt’s with this romantic vision in mind that I visit Gibraltar Point at the southern tip of the Toronto Islands, to get a closer look at the Forestry Island colony I had only seen from the water. But if I was looking for a stylized performance of revolution, Toronto’s cormorants foil me, just as they foil the managers at Leslie Street Spit and the boat owners along the waterfront. The birds are flying around and grunting. Almost all activity is directed toward a few trees on the shoreline, to which dozens (hundreds?) of birds are carrying strips of plastic for their nests, getting into squawking sessions or little fishing trips along the way. Only about three trees are skeletonized, and they contain nest structures that are stacked like condos (cormorants have localized architecture styles, and in Toronto, they basically build high-rises). I was expecting a goth opera. Instead, I get something as annoyingly familiar as College Street, or Harbourfront: another Toronto neighbourhood filled with puking, shitting, noise and construction. One of them does the wing-drying pose and it looks like a construction worker stretching his back after a long session on a drill.

It’s one of many ways cormorants have appeared to me over the course of my reporting, and as good a place to stop as any. Enemy or antihero, invader or neighbour, whatever story I try to tell about cormorants is ultimately replaced by another. Cormorants resist attempts to describe or define them as surely as they evade bullets and infrastructure. If cormorants are symbols of the Other, as many have suggested, part of co-existing with them is recognizing and respecting this unknowability, as well as the ways they’re familiar. I remember something else Swanson told me, which is that the difference between species can be an opportunity for connection as much as conflict. “We’re living together,” Swanson said simply. “Our world is influencing their world and their world is influencing ours. And we need to learn to become comfortable with that, if we want to survive into the future.”

Correction—June 19, 2025: This article has been amended to correct the number of cormorants on Middle Island.