The Delta Kappa Epsilon mansion was still sticky with beer when William Vinall was shown around the rental room. It was April 2024. The fraternity’s end-of-year party had wrapped up only hours before. Vinall could tell: the brothers and the house still appeared hungover. His shoes stuck to the floor as he was given a walk-through. An alumni member promised him that the frat boys would clean up, Vinall later recalled, and said that if he moved in, the frat might even invite him to future parties.

Vinall, then 23, goes by his middle name Floyd. He was between places, and the frat was the only spot that had responded to his month-long apartment search. He had some savings, but by his own admission, his credit was “not great,” and he was still looking for a job. Between growing up in foster care in Hamilton, Ont., crashing on couches, and living with previous romantic partners, he had never had particularly stable housing. He hoped that moving to Toronto from Hamilton would give him a fresh start.

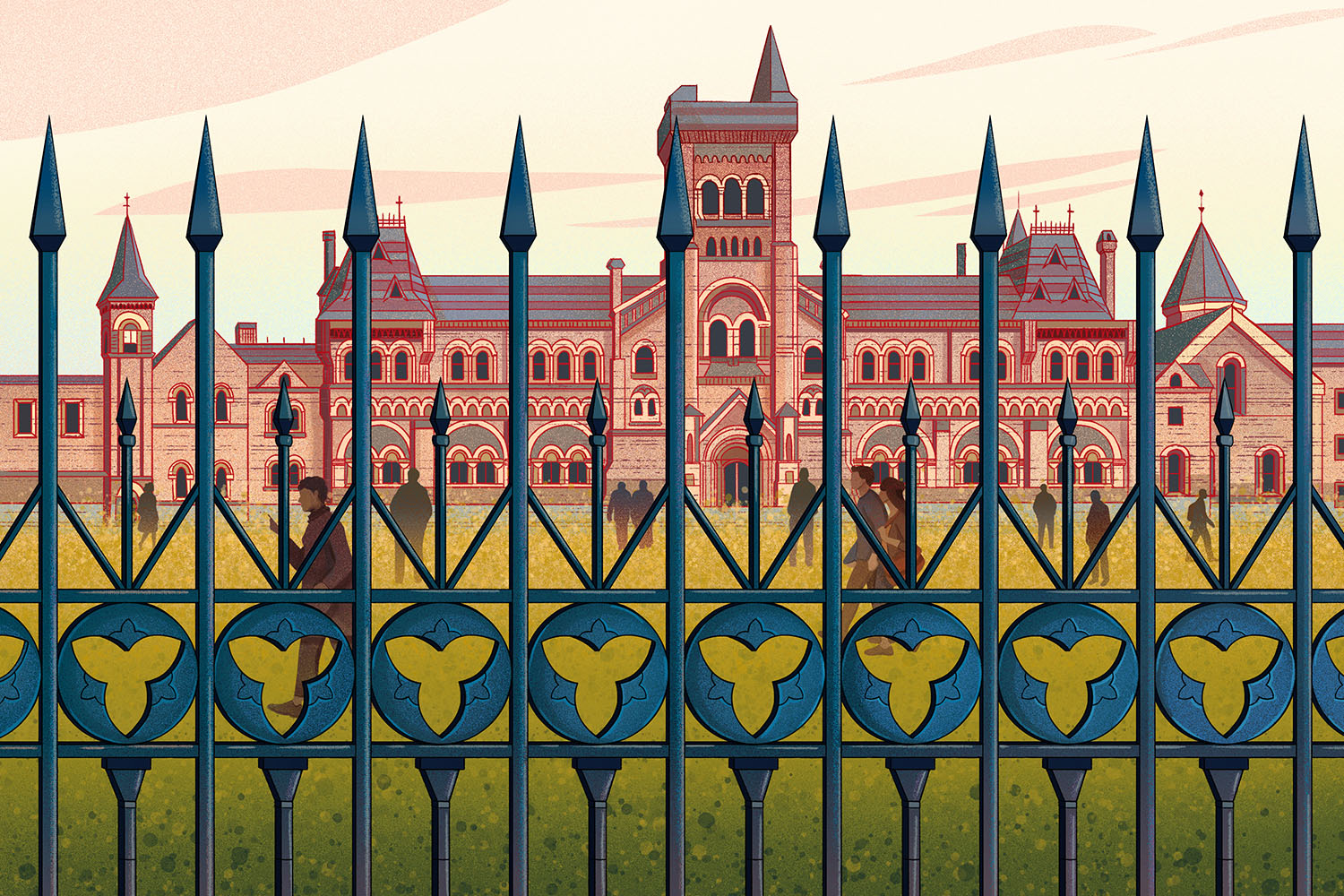

A rental listing on Facebook for the room at the chapter house of Delta Kappa Epsilon, also known as DKE or Deke, had seemed promising to him. The hulking brick mansion, with fading Greek letters on the exterior, was a three-minute walk from the St. George subway station. Located at the corner of St. George Street and Lowther Avenue, it neighboured stately homes with landscaped gardens in one of the most desirable areas in Toronto.

The room itself wasn’t much to look at. It was a cramped space with a sloping ceiling, barely wide enough to fit a double bed. The brothers inexplicably called it “the Thunderdome.” The door to the room was spraypainted with a cloud and messy black letters that read, “THUN-DER.” There were holes in the drywall of the hallways. But at $850 a month for a room in a prime location, the price was right. And DKE wasn’t doing a reference check. Within 24 hours, Vinall signed the occupancy agreement.

“I remember saying, this will either be the best decision or the worst decision of my life,” he told me.

Join the thousands of Torontonians who've signed up for our free newsletter and get award-winning local journalism delivered to your inbox.

"*" indicates required fields

It did not go well. Part way through the year, Vinall fell behind on rent. Then early this March, 11 months after moving in, he received a WhatsApp message from the frat, informing him he would have to move out at the end of the month. A follow-up message more than two weeks later reinforced the point: “Just know we need to collect rent to pay bills Hydro, electricity heating, and house repairs are not free. We are barely surviving. We need to get rid of all the people who cannot pay rent so you must leave thank you. Please understand.” Vinall asked for leniency. But after he was told the frat’s alumni board would not consider his request for an extra month’s grace period, his relationship with the brothers quickly soured. Vinall accused the frat of being a bad landlord and the frat accused him of being a nightmare roommate. He sought help from the Landlord Tenant Board to prevent DKE from throwing him and his belongings out.

Vinall began looking for someone with whom to share his story, which is how he found me. As an undergraduate sociology student at the University of Toronto and news editor of the campus newspaper The Varsity, I had often walked past the fraternity houses near campus, and heard stories—not altogether flattering—of the raucous parties some of them host. But until Vinall contacted me over email at the campus newspaper this spring, seeking media coverage of his dispute with DKE, I was unaware that several of the fraternities had become home to non-frat members like him.

To compensate for low occupancy levels among their members, these fraternities have become de facto landlords, renting out rooms in their chapter houses to members of the public who are desperate for cheap rent. Yet even though these fraternities are acting like landlords, renters say they don’t always abide by the provincial rules and responsibilities that come with that role. Meanwhile, a long disputed loophole in Toronto’s city bylaws means they aren’t regulated in the same way as other forms of rental housing, like apartments or rooming houses.

The lack of regulation and oversight isn’t ideal for anyone who lives in a frat house. Non-member renters, whom the frats call “boarders,” may be subject to unfair evictions, unorthodox rental requirements, invasions of privacy, and dismal—even squalid—living conditions. Meanwhile, fraternity brothers, young university students often living away from their families for the first time, may wind up sharing a home with individuals who aren’t adequately vetted and whose aims, lifestyles, or personalities aren’t compatible with student life.

Fraternities didn’t always provide housing. In the late 18th century, when the first fraternities emerged in North America, members gathered in meeting halls or dorm rooms, and later, in spaces they rented from organizations like the Elks Lodge. It wasn’t until the 1880s, once they had developed a powerful alumni base, that fraternities and sororities began purchasing or renting stately homes in residential neighbourhoods at the peripheries of universities to provide communal housing for their members, according to Pietro Sasso, an associate professor of higher education at Delaware State University who has edited three books on fraternities and sororities.

As university enrollment surged during the post-World War I boom, fraternities and sororities became a major purveyor of post-secondary housing.

“That’s sort of how, historically, fraternities and sororities got into the college housing business,” Sasso said.

The Toronto chapter of DKE, known as the Alpha Phi chapter, followed that trajectory, starting out in 1898 by holding its meetings in the seventh-floor room of a building at Richmond and Bay Streets. By 1906, as the chapter prospered, according to DKE’s website, it acquired a house at 91 Wellesley St., which housed 20 brothers. The fraternity moved several times before eventually purchasing its current property, 157 St. George St., at the edge of the University of Toronto campus. On its website, DKE says it bought the house from the Eaton family in 1964 for one dollar, although property records say it was two—a bargain at any rate.

Until the 1970s, North American university students weren’t typically assigned housing before they showed up for school. So when they did arrive, descending on university towns, they’d rush from the train stations to find the best housing, Sasso said—which, for a long time, was a fraternity or sorority chapter house. This, he explained, is where the concept of “rush” came from. Today, “rush” refers to the early weeks of September when fraternities and sororities recruit new members.

New students living in these houses were expected to eventually become members, and if they didn’t wind up joining the fraternity or sorority, they’d be kicked out.

In the 1960s, however, amid a counterculture movement that challenged the traditions and values of previous generations, fraternities and sororities lost some of their popularity. Suddenly, unable to fill their houses and desperate to stay afloat, some began renting out rooms to non-members.

“That’s kind of how we got here,” Sasso said.

When a fraternity starts renting out to non-members, according to Sasso, that’s usually a red flag—a sign “that there’s other problems within the health of the organization as a chapter.”

Fraternities tend to operate like franchises. There’s normally a national office, which shares its name and practices with local chapters across the U.S. and Canada. But each chapter house is locally managed, often by a volunteer board of alumni and incorporated as a limited liability company, or LLC, according to Sasso. These boards may meet only episodically, which leaves the members themselves, young 18- to 23-year-old men, to run the local chapters. Typically, their main sources of income are membership dues, social events, house rent, and alumni donations.

Given the lack of supervision, life at a fraternity can devolve “in some scary ways,” Sasso said. “It reminds me of Lord of the Flies.” (By contrast, the management structure of sororities is usually much more centralized, with greater alumni involvement, and their national offices often rely on a professional maintenance company to take care of their properties, he explained.)

At a fraternity, once the conditions of a chapter house start to deteriorate, fewer young men tend to want to live there. “And then it snowballs,” Sasso said. With fewer occupants, the fraternity may be forced to rent out its rooms to make up for the financial shortfalls, and if the revenue stream from dues-paying, live-in members dwindles, there’s less money to keep the house in good repair.

The Toronto chapter of Delta Kappa Epsilon boasts of a distinguished history. Its website names some of its illustrious past members, including George Drew, who was premier of Ontario from 1943 to 1948, and artist Lawren Harris of the Group of Seven. But if there are any alumni who became public figures after the early ’90s, they aren’t listed on the chapter’s online honour roll. The fraternity does, however, name-drop famous alumni of its affiliated DKE chapters in the U.S., including former presidents like Theodore Roosevelt, Gerald Ford, George W. Bush, and George Bush Sr. (The U.S. has always had a more robust fraternity and sorority culture than Canada. While fraternities and sororities saw a dip in membership during COVID and the #MeToo movement, their popularity has since rebounded amid a new wave of conservatism, bolstered by the second Trump administration.)

The Toronto chapter’s house itself, which municipal records show was assessed at $3.25 million in 2025, has seen better days. Constructed in 1898, the once-impressive mansion sags from decades of delayed maintenance and fraternity wear and tear.

DKE is a non-profit organization. One can only imagine how much it would cost to restore the house and keep it in good repair.

The foyer has retained some of its glory. During a visit this summer, the first thing I noticed was an elegant wooden staircase where the frat takes its yearly pledge class photo. Plaques and member photos hung above the fireplace in the front room. But as I ventured deeper into the house, the air itself became thick and stale. Upstairs, uncovered lightbulbs illuminated exposed wires.

One recent renter, Luke, a newcomer to Canada who was in Toronto on a work visa, told The Local that he found the frat house to be infested with mice while he was living there between March and August. (Luke has been given a pseudonym to protect his identity while he is applying for permanent resident status in Canada.)

“The rodents run wild and free in the house,” he said, explaining they would scurry across the stove top of the communal kitchen. One of Luke’s regular chores was to clean the dining hall—an unpleasant task. “We’re talking about rodent feces everywhere,” he said.

Luke said he was one of eight or nine non-members among 17 people who lived at the house this summer. He’s in his late 20s; he estimates at least three occupants were middle-aged or older. He said he occasionally helped another renter, whom he befriended, do minor repairs around the house, like patching up holes in the drywall or fixing the communal toilets. His friend had some experience with home renovations, but Luke believed what the house really needed was a proper contractor, which would have been costly to the frat.

“The property, it’s almost falling apart by itself,” he said.

It’s unclear when DKE started renting out its rooms to non-members. One Facebook ad I found was posted as early as August 2016. The fraternity declined The Local’s requests for an interview with someone who could speak on their behalf for this article. A response from an email address labeled “President DKE Toronto” stated they had no comment at this time.

Local Journalism Matters.

We're able to produce impactful, award-winning journalism thanks to the generous support of readers. By supporting The Local, you're contributing to a new kind of journalism—in-depth, non-profit, from corners of Toronto too often overlooked.

SupportIn May, the dispute between Vinall and DKE made its way before the Landlord Tenant Board. Vinall alleged the fraternity violated his tenant rights—that frat members entered his rental unit illegally, switched the locks without giving him a replacement key, “substantially interfered” with his “reasonable enjoyment” of the place, and “harassed, obstructed, coerced, threatened or interfered with” him. The fraternity’s lawyer Rocco Achampong disputed these allegations, and accused Vinall of having engaged in “fraudulent misrepresentation” to live at the house by telling the frat he would be attending the University of Toronto as a student, when, in fact, he did not. (If being a student or prospective student at the university is one of the frat’s requirements for living at the house, it appears that did not apply to Luke. Luke was not a student, and was employed under a work visa while he was living there this summer.)

In our interviews, Vinall, a dark blonde, solidly built now 25-year-old, shared with me more details of what he characterized as the frat’s poor treatment. Among other things, he alleged he and other renters were required to either leave the house or stay in their rooms whenever the frat held parties or other functions, which happened with little notice. (Luke separately said the same.) He also alleged that as part of his rental agreement, he was assigned chores, like cleaning the third-floor bathroom, and had additional tasks like weeding the parking lot. He had been willing to comply, and everything had been fine, until, he said, the frat told him he had to leave so they could give his room to a frat member. That’s when he sought legal help. Then, it all went downhill. He alleged the frat members bullied and belittled him, and intentionally yelled and slammed doors to startle him, triggering his post-traumatic stress disorder.

Luke said he witnessed frequent conflict and tension between the frat members and renters, including Vinall. Frat members tended to treat the renters as though they were doing them a favour by letting them stay there, he alleged; “I don’t want to get rude and, you know, to flourish my language, but you’re basically their bitch.”

But the other renters could be challenging to live with, as well, Luke said. One of the reasons he left, he said, was because he felt he couldn’t invite female guests over to a house full of men—not because it was against the rules, but because he worried they’d be harassed or exposed to unseemly behaviour, especially if people at the house were using illegal substances or in an otherwise poor mental state. “Because we also share toilets…I would have to go and, you know, escort them to the toilet myself because the thing is, you never know who’s gonna be there, and you never know what kind of state they’re gonna be in,” he said.

At the Landlord Tenant Board hearing, Achampong confirmed there are periods when the frat’s “boarders” aren’t allowed to access the property. As part of the frat’s tenancy agreement, he said, occupants agree to vacate the house for up to 14 days in the fall—around the pledging period for new members—if they’re given at least 30 days notice.

Kunal Gupta, one of two DKE house managers who started this role this school year, also told me that non-member renters have little housing security at the chapter house. “We can always kick them out if more brothers want to live in the house, because they’re the priority,” he said. (Gupta didn’t speak on behalf of DKE, but agreed to talk to me about his personal experiences and observations at the frat.)

Gupta told me that certain non-members aren’t easy to live with, but that he and his frat brothers try to maintain a good relationship with them. “Some people are chill; some people are not fun to live around,” he said, but declined to elaborate.

Vinall admitted he wasn’t a model tenant. He was chronically late on rent. Last winter, when he was unemployed and dealing with a breakup, he was also in poor mental health.

At his hearing on May 9, the Landlord Tenant Board held off addressing Vinall’s allegations against DKE. It focused instead on whether the provincial Residential Tenancies Act, which protects tenants from unlawful evictions and sets out the responsibilities of landlords, applied in this case. (It found it did.) Nevertheless, the proceedings confirmed that DKE rented to members of the general public out of necessity. T’ai Simm-Smith of DKE, who appeared at the hearing as the “landlord’s agent” for the fraternity, told the Landlord Tenant Board that the fraternity rents to non-members in “extreme cases of low occupancy.” Early in the COVID pandemic, for example, Simm-Smith said, “we rented to the public to survive.”

When reached via Facebook, Simm-Smith told The Local he was advised by DKE’s board of directors not to give any interviews. Later, when The Local sent him and the frat a long list of questions, Simm-Smith wrote back via email. “William Floyd Vinal [sic] will be charged by the Toronto police” for alleged misconduct, he wrote. (This information could not be verified. Toronto Police Service said this was not something they could confirm, and any such information would only be made available if an individual was charged. Vinall denied any wrongdoing and said he had not been contacted by police.) Simm-Smith ended his brief email saying, “Nothing further.” He did not answer any of The Local’s questions about the condition and maintenance of DKE’s chapter house, the renting of their rooms, or how they vet renters and manage conflicts at the house.

DKE also isn’t the only Toronto fraternity renting to non-members. In an email, Elisabeth Brückmann, the executive director at West Toronto Community Legal Services, said there are “a number of frat houses that rent out rooms to members of the public and have not understood that the rules of the RTA [Residential Tenancies Act] apply to these tenancies.” Her legal clinic has assisted “a number of tenants living in frat houses over the past few years,” she explained. (Vinall had sought legal assistance from her clinic.) Among the violations they’ve reported to her clinic are non-functioning locks on room doors, invasions of privacy, squalid conditions in common areas, bullying and harassment, and threats of eviction, she said.

Through a search of advertisements on Facebook, email inquiries, Instagram messages, and phone calls to all 13 fraternities that have chapter houses near the University of Toronto, I discovered at least 10 were either offering or had offered to rent to non-members within the past six years. A few told me they rented out rooms exclusively for the summer. Others, like Theta Delta Chi, advertised rooms for rent throughout the year.

When I reached Theta Delta Chi’s president Kameel Ahamed via Instagram message in July, he told me his fraternity occasionally will have renters who are “more or less considered friends of the house from a social perspective.”

Ahamed said there were four non-members renting from his fraternity at the time. But when later reached by email for an interview, Ahamed declined. He said the frat had no comment and they were unavailable for an interview “for the foreseeable future.”

The general disrepair and lack of upkeep at certain frat houses in the Annex, their garbage, and especially their noisy parties, have long caused headaches and worries for the neighbourhood’s residents. And their practice of renting out to members of the public is well known among longtime residents. Yet over the years, repeated attempts at the municipal level to regulate Toronto’s fraternities and sororities, which are exempt from the City’s licensing requirements for rooming houses, have failed to result in concrete action.

The issue was most recently brought before city council by Councillor Dianne Saxe in January 2024. In a letter to the City clerk and members of the planning and housing committee, Saxe raised the idea of requiring fraternities and sororities to have a license to provide accommodations. She noted that a new multi-tenant house licensing bylaw that was going into effect that March was meant “to ensure that those who pay to occupy dwelling rooms have a safe, adequate and dignified place to live,” and suggested fraternities and sororities should not be exempt from it.

Her motion did not pass. Saxe declined to speak to The Local.

In his submission to the committee on this issue, Kevin Tuttle, president of the SoFra Federation of Toronto, which represents fraternities and sororities in the city, argued that his federation’s members had been providing “safe and affordable housing to 300+ students for more than 100 years.” The definition of a multi-tenant house did not apply to them, he wrote, because their student members live together as a single housekeeping unit, sharing chores, meals and expenses among other things. Their student members don’t “rent” single bedrooms from the fraternities and sororities, he said; rather, members are “owner-occupiers.” (He made no mention of non-member renters.)

Had the exemption been lifted, fraternities and sororities would have been required, under the multi-tenant house licensing bylaw, to obtain a license, develop property maintenance plans, and comply with various codes like the building, fire, and electrical safety codes. Tuttle’s submission stated that as private residences, sorority and fraternity chapter houses did not need to comply with such codes. To do so, he wrote, “may require hundreds of thousands of dollars in retro-fitting to our heritage homes which as small not-for-profit organizations we can ill afford.”

Reached by email, Tuttle declined to comment for this article.

Currently, renters living at fraternity houses have little recourse if they have complaints. All they can really do is inform their landlord of maintenance or other issues, and remind them of their obligations under the Residential Tenancies Act, according to Douglas Kwan, director of advocacy and legal services at the Advocacy Centre for Tenants Ontario (ACTO). If the landlord fails to abide, they can go to the Landlord Tenant Board, but that often results in irreparable damage to the landlord-tenant relationship, Kwan said. Plus, wait times for a hearing at the Landlord Tenant Board are currently three to seven months, he said: “That’s a long time where that person could be exposed to many incidents of harassment and intimidation by the landlord, hypothetically.”

Moreover, he said, people renting rooms from fraternities may be living on the margins and in precarious positions, and thus unlikely to pursue such measures. Ultimately, Kwan said, “It’s just another example of how people are just desperate to find housing in Toronto.”

After the preliminary hearing at the Landlord Tenant Board, Vinall and DKE reached a settlement. Vinall could stay until the end of August and the fraternity decided he didn’t have to pay the rest of the rent he owed.

Vinall’s final day at the chapter house was Aug. 31, 2025, two days after DKE’s first party of the school year. He had recently been let go from his latest job as a line cook, and the small severance package was enough to cover a rental fee for a U-Haul.

I had come to meet him at the chapter house for another interview, but he arrived very late, with an hour until midnight to move out. When I saw how much stuff he had to move, how many bins of books, I felt compelled to help out. As much as I wanted to maintain some professional distance as a journalist, I couldn’t just stand there and watch him struggle. I picked up one of his boxes and carried it downstairs. Several young men watched on high from the fire escape stairs.

“Moving out or in?” one young man asked, as Vinall and I passed in the hall.

Vinall told me he was going back to Hamilton. He had no job or apartment lined up. He had no plan but to go back to sleeping on family member’s couches.

As of late September, DKE had two rooms listed for rent on Facebook Marketplace. One of them was the Thunderdome.

“Room for rent in the annex two blocks away from the subway station st George,” the ad read in erratic punctuation. “…Occupancy agreement must be signed minimum four months maximum one year.”