What forced Anisa Carrascal to the emergency room one late September morning last year was an intense pain, simultaneously stabbing her lower back and burning through her abdomen. She was worried it was a kidney stone stuck somewhere. That had happened before, and she’d had to have it surgically removed. So not only was this new pain excruciating, but she was aware that leaving it untreated could compromise her kidney.

She went to the closest ER, at the Royal Victoria Regional Health Centre in Barrie. She recalls the waiting room as a maze of glass walls. She found a seat, but she couldn’t get comfortable. That was unfortunate because, like most of the people in that coughing, groaning, overstuffed room, she was going to spend the majority of her ER visit in a chair.

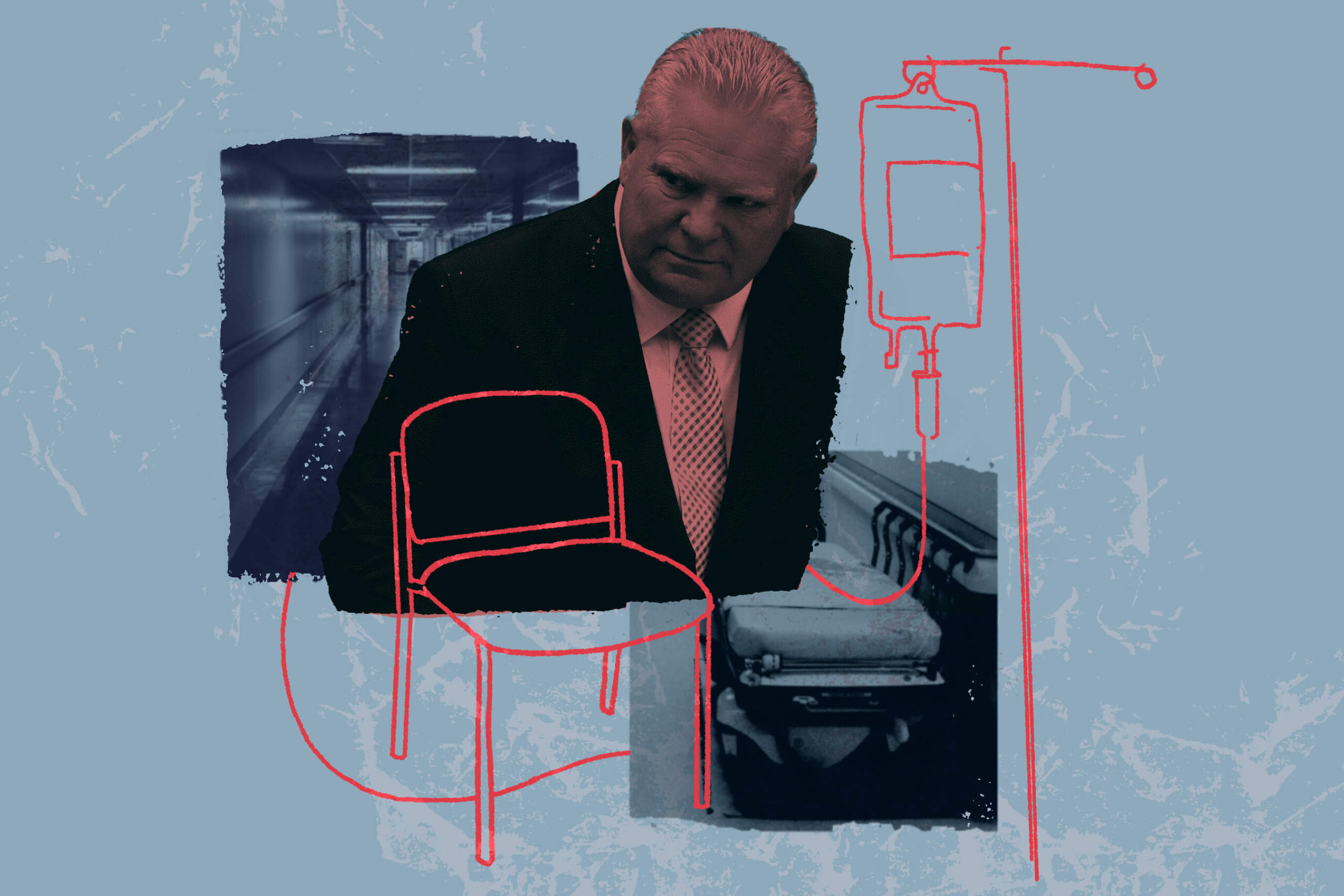

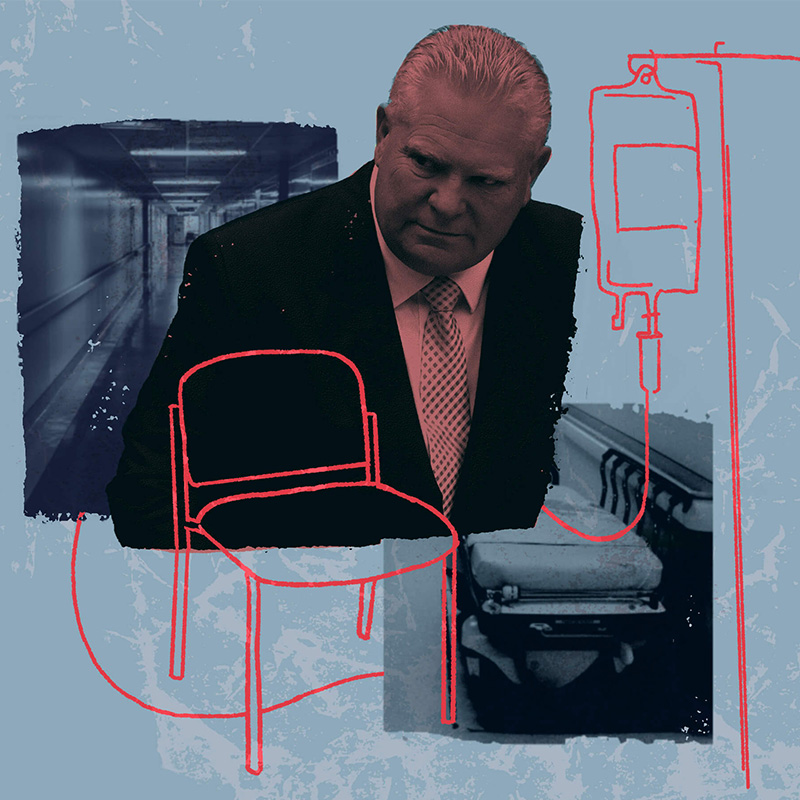

The words “hallway health care” entered the Ontario lexicon around a decade ago, a metaphor for massive overcrowding in our hospitals. But many medical professionals say things these days are even worse. “I would love a hallway stretcher,” says Raghu Venugopal, an emergency doctor who works in three separate Toronto hospital emergency departments. He says that, looking back, hard as it is to believe, hallway health care was actually “the golden era” of his 18-year career. “We’re now in the era of chair medicine,” he says.

It’s impossible to do a good physical exam when a patient is propped up in a chair, he says. Usually he shuffles people away to try to find a modicum of privacy, maybe in a corner of the waiting room or behind the triage station, where he can take a health history and not be overheard by everyone in the room.

Sometimes, if he has to do an exam that is especially intimate, he sets up a temporary stretcher off to the side somewhere, and surrounds it with screens. “I am doing rectal exams in hallways,” he says.

Then after a discussion with the patient and the family, and after he orders whatever tests are needed, he just shuffles them back out to a chair in the waiting room.

He’s witnessed 90-year-olds slumped for hours in wheelchairs. Sometimes they’re in soiled undergarments, he says, or their private parts are exposed. “They haven’t been fed, they haven’t had a drink of anything. They haven’t had their usual medications,” he says. “You ask the nurses, who are trying their best, who are human beings, ‘Can you please find this woman a stretcher?’ and you repeat the order, you put it in writing, and nothing happens, because there is no bed to put an older woman into.”

Carrascal, age 45, said that at the Royal Victoria, chair medicine was so entrenched there was a mobile team that went chair to chair doing blood work. Her pain meds were also injected while she was in a waiting room chair. Her medical history was taken while in a chair. The only time she left it was to get a CT scan, when she was put on a stretcher for about 20 minutes. But after the scan, she went back to a chair. In total that day, she spent the better part of 11 hours sitting upright, most of that time in a lightly padded chair, with metal tubes for armrests.

Eventually a doctor told her she had diverticulitis, a condition where irregular pouches in the colon wall become inflamed, but he didn’t say what that meant for her or how she should proceed. He gave her a prescription for antibiotics and told her to ask her family doctor for a referral to a specialist. Then he moved on.

“I don’t have a family doctor,” she says. Four years earlier, she’d been notified that hers had switched clinics. When Carrascal called to see if she could be kept on the roster at the new clinic, she was told she’d have to pay $4,245 a year to do so—her doctor was now working for a so-called “executive health clinic.” In exchange for the large annual fee, it promised same-day office visits, email consults, and even house calls.

Carrascal hadn’t been able to find a replacement doctor, and had been relying on walk-in clinics ever since.

Before she left that night, Carrascal, a registered practical nurse who had worked in a Toronto ER at the beginning of her career, asked for her discharge summary. That’s a document that details what happened during a hospital stay—all the tests performed, the results, medications ordered, the diagnosis, and a treatment plan. But a nurse told her they didn’t give those out any more.

Carrascal was outraged. “For me, as a nurse who has worked in a hospital for seven years, I’d never discharge a patient without a discharge note,” she says. She couldn’t believe it, so she double-checked with an administrator in the ER. That person gave her a pamphlet that directed Carrascal to a website where she could, in fact, access the notes—for a fee.

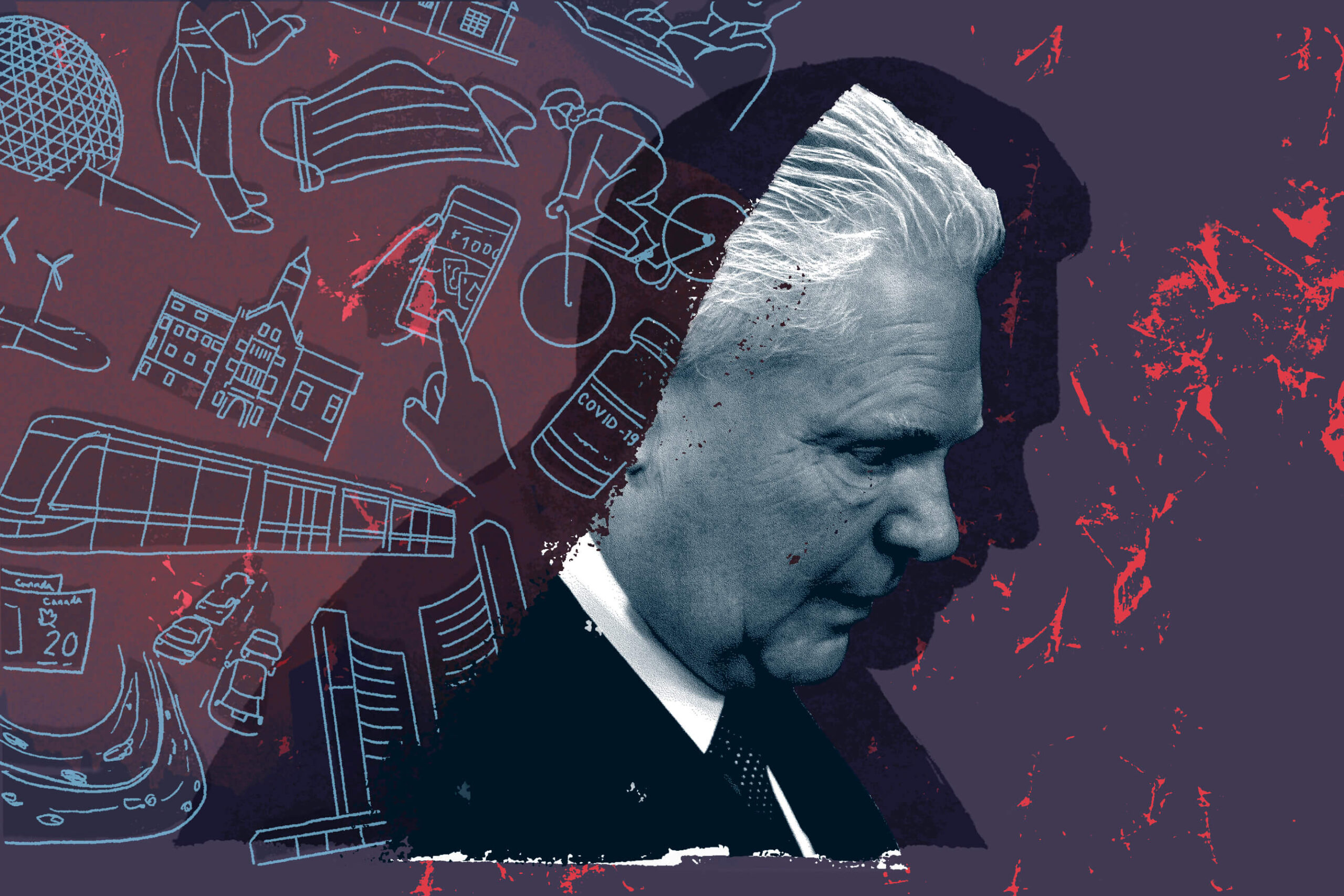

When Doug Ford became premier in June 2018, one of his first priorities was to end hallway health care. The province had just suffered through a brutal winter. Wait times in ERs were legendary and hospital overcrowding was in the news almost every week.

The problem wasn’t ER patients per se, of course. It was that patients were being “admitted” into hospitals where all the beds were already taken. So those admitted patients waiting for beds were put into emergency department beds intended for people like Carrascal. And when those beds filled up, the admitted-but-waiting patients were put onto stretchers in hallways, closets, conference rooms, even bathrooms.

That winter before Ford became premier, about a thousand inpatients every day across the province were languishing in makeshift hospital beds. It wasn’t only that they lacked comforts like lights that could turn off, a privacy curtain, or a nurse call button. Much more importantly, it meant that technically there was no staff being paid to care for them—no nurses, no therapists, no food service workers, no cleaners. Of course those professionals did care for them, but they did it on top of an already full caseload.

It’s like getting on an airplane where everyone has an extra passenger in their lap. The already tight legroom gets tighter, the slow delivery of meals gets slower, the line to use the toilet gets longer. Maybe you get where you’re going, but it’s a much more harrowing journey than you’d expected.

Ford vowed to put an end to that indignity.

Join the thousands of Torontonians who've signed up for our free newsletter and get award-winning local journalism delivered to your inbox.

"*" indicates required fields

In October 2018, just months into his mandate, his government issued a press release proclaiming, “Ontario’s Government for the People Taking Immediate Action to End Hallway Health Care.” He established a committee called the “Premier’s Council on Improving Healthcare and Ending Hallway Medicine,” with 11 prominent health experts who would study the issue and report back quickly on causes and solutions.

In their January 2019 interim report on causes, the council identified many of the usual suspects. They nodded, for instance, to long-recognized issues like population growth and how an increasing share of that population is elderly.

They also acknowledged the all-important throughput problem—that what goes in one end of a hospital has to come out the other, otherwise things get gummed up inside. Hospitals are designed to deal with “acute” problems, like surgeries and heart attacks and cancer. But just because a hospital has done all it can do for a patient doesn’t mean the person has no further care needs. They might need rehab or home care or long-term care or supportive housing. But Ontario just didn’t have enough of any of those things. So patients who didn’t need hospitals, but couldn’t access the post-acute care they needed, got stuck there.

When the Premier’s Council’s second report came out a few months later, with a set of 10 jargony and facile recommendations, it presaged what was to come. Almost seven years later, Ford’s record on health care speaks for itself.

In January 2018, months before he became premier, an average of 1,372 patients per day across the province were without actual hospital beds and being treated on stretchers in hospital hallways and other so-called “unconventional spaces.” By January 2023, that number had increased to 1,521, and by January 2024, it had grown to 1,860, according to Ontario government data released to The Local after a Freedom of Information request.

The data, first reported by The Trillium, also shows that GTA hospitals have been especially hard hit. Comparing daily averages from January 2018, before Ford came to office, with those from January 2024, after 68 months of Ford in power, some hospitals saw their hallway numbers more than double. At Sunnybrook, for instance, the average number of patients being treated in an unconventional space each day rose from 16.6 to 35.4. Oakville Trafalgar Memorial Hospital (formally Halton Healthcare Services) went from from 26.2 to 58.1. Credit Valley Hospital and Mississauga Hospital (Trillium Health Partners) went from 83.6 to 185.5. Michael Garron (Toronto East Health Network) jumped from 5.4 to 25.9.

Meanwhile, in smaller Ontario communities, like Perth, Chesley, and Red Lake,

emergency departments were forced to close altogether—sometimes just overnight, sometimes for a weekend, sometimes for days on end. They didn’t have the staff to stay open.

According to Natalie Mehra, executive director of the Ontario Health Coalition (OHC), a group that advocates for public health care, local emergency department closures in the province were extremely rare before 2018. But under Ford, they became routine. Between January 1 and November 24, 2023, according to the OHC, which actively tracks such shutdowns, there were 868 emergency department closures in Ontario. In the three years between 2022 and 2024, according to the CBC, more than one in five local emergency departments in Ontario had experienced at least one unplanned closure.

“All of health care,” says Mehra, “it’s in the worst disarray we’ve ever seen.”

What goes in one end of a hospital has to come out the other, otherwise things get gummed up inside.

One way to not run out of hospital beds is to have enough of them. Notably, Ford’s special council didn’t focus on increasing capacity as a key way to ease the hallway health care crisis. That is despite the fact that Canada—and Ontario within it—has among the lowest rates in the developed world for staffed hospital beds per capita.

The Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) is a club of developed nations that, among other things, tries to establish and report on various international standards. Among the data it collects are numbers of funded hospital beds per population. In 2021, for instance, Korea had 12.8 beds per 1,000 people. Germany had 7.8, Austria had 6.9, France had 5.7. The average for all OECD members was 4.3 per 1,000. Canada had only 2.6.

Worse, within Canada, Ontario ranks the lowest. According to OHC numbers, based on 2022 data from the Canadian Institute for Health Information, Ontario had just 2.28 beds per 1,000 people. The average of the other provinces (excluding Quebec, which does not report) was 3.02.

To be fair, the Ford government did add some beds during the past seven years. In 2018, there were 31,720 hospital beds staffed and in operation in the province,

according to the Ontario Council of Hospital Unions (OCHU). And by 2023, there were more: 34,931. Alas, those additions did not nudge our province out of last place in the country.

More staffed beds, of course, means more staff. According to the OCHU, for Ontario hospitals to have the same level of staffing as other provinces, we’d have to add 34,292 full-time workers—for everything from cleaning and food services to intensive care units to operating rooms to emergency departments. Significantly, we are short 15,396 inpatient nurses, it said in its 2025 pre-budget submission to the Ontario Legislature’s Standing Committee on Finance and Economic Affairs.

No one has forgotten that, rather than doing everything it possibly could to recruit more medical staff, Ford illegally capped their wages with Bill 124. That law was subsequently deemed unconstitutional, but the restrained wages, overwork, dangerous nurse-to-patient ratios, and poor morale that it caused in the interim bled Ontario of the very health workers it needed, says Mehra.

In its 2023 budget, the province committed to adding 3,000 new hospital beds over 10 years. The province’s Financial Accountability Office (FAO), which provides independent analysis of provincial finances, estimated that just 1,000 of those would be added by 2027-28. “Despite this increase in hospital beds, the FAO continues to project that demand for hospital services will outpace the addition of new beds, relative to 2019-20,” it stated in a May 2023 report, “due to Ontario’s growing and aging population.”

That’s us: growing and aging. When Ford took office, Ontario had 14,251,136 people, and by June 2024, there were 16,033,583—an increase of 12.5 percent. Just to tread water at the bottom of the OECD list, we will need to keep adding beds.

And as the FAO suggests, population increases alone are not the whole story. Not only is the share of over-65s growing, but we are living longer—living more years as old people. Increased longevity is all fine and well, but it means we can expect that each person will require even more health care during their lifetime. Without more hospital beds and more post-acute care in place, that pesky throughput problem will only get worse.

In 2018, when Ford took office, the waitlist for long-term care in the province was 35,000, according to the FAO. That fall, Ford committed to adding 15,000 new long-term care beds over five years. They weren’t all built (the Ministry of Long-Term Care refused to say how many were), but the FAO noted that even if they had all come into operation, an additional 55,000 new long-term care beds would be needed by 2033 to simply maintain the waitlist at around 36,900.

7 Years of Doug Ford

Like this story? Don't forget to check out the rest of the issue.

Ford’s government introduced legislation, the “More Beds, Better Care Act” in 2022, which gave priority to patients in hospitals over patients in the community in accessing post-acute care beds. The same legislation made it possible for hospitals to move such patients out against their will, to facilities that they didn’t consent to, up to 70 kilometres away from their preferred location (150 kilometres for patients in the north).

By autumn 2023, according to the government’s own numbers, the waitlist for long-term care beds had grown to 43,000.

In the 2023 budget, besides promising new hospital beds, Ford again promised more long-term beds. He pledged money to build 31,000 new long-term care beds by 2028, and to redevelop 28,000 existing ones. The Ministry of Long-Term Care refused to say how many, if any, of those beds have been built so far—it advised The Local to file a Freedom of Information request—but it did confirm that as of January 2025, fewer than 23,400 of the 59,000 beds pledged have even been approved for construction.

“We knew 80 years ago how many 80-year-olds would be here today—or a good estimate—and yet we have, for decades, not prepared appropriately,” says Carolyn Snider, vice-chair of the public affairs committee of the Canadian Association of Emergency Physicians, and former physician chief of a Toronto emergency department. She laments that governments so often fail to use evidence to guide their policies.

She believes that if we wanted to, we could redesign our health system to be extremely effective and efficient. “There is so much data that could be used to forecast what we need, where we need it and how to deliver it,” she says. But that’s not being done, she says. We never seem to look at the big picture.

“It’s incredibly frustrating to see so much of our basic health care being driven by politics and four-year election cycles,” she says. “Until we move away from that fundamental reality, we aren’t going to be able to invest in and reorganize a healthcare system, because it’s going to take longer than four years for any benefit to be seen.”

“We knew 80 years ago how many 80-year-olds would be here today…yet we have, for decades, not prepared appropriately.”

Not everyone is convinced that fixing health care is a priority for this government. Allowing the public system to deteriorate might break public trust in it just enough that more privatization becomes palatable.

“The will is not there to fix the public health system,” says Mehra. “They just want to privatize it.”

In the run-up to the June 2022 election, Ford’s team strenuously denied this, calling claims that the government was looking to allow more for-profit health care in Ontario “categorically false.” The “use or function” of for-profit facilities in Ontario “is not being expanded or changed,” it said.

But just a couple of months later, the newly-re-elected Ford government announced plans to expand the numbers and types of procedures that could be done through private facilities—using public money—and the following spring, they introduced new legislation to support that.

The government said it was doing this in order to increase capacity and reduce wait times, but a report by the Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives (CCPA), a policy think tank, pointed out that “capacity depends on the availability of qualified staff, which is unchanged by the addition of profit.” Ontario need only look at what has happened in provinces that are further down the for-profit road—Alberta, Saskatchewan, Quebec—says Andrew Longhurst, a health policy researcher at Simon Fraser University and author of the CCPA report, to see that such a strategy doesn’t improve wait times, but rather worsens them.

The report noted that even as more of Ontario’s health dollars flowed to for-profit facilities, many operating rooms in public hospitals were sitting idle for hours each day. Why not give the money to the public hospitals that we’d already built so they could afford staff to carry out the needed procedures, asks Longhurst, rather than siphon off resources and staff to for-profit facilities?

It is a reasonable question, especially given that surgical procedures at for-profit facilities typically cost more than at public hospitals. (The payments to surgeons are the same but the facility fees are different.) According to CBC, a Freedom of Information request revealed that cataract surgery in a public hospital cost the province $508, but the same procedure at the Don Mills Surgical Unit Ltd.—a for-profit facility—cost $1,264. A knee surgery involving meniscus repair, the CBC reported, cost between $1,273 and $1,692 in a public hospital and $4,037 at the Don Mills Surgical Unit Ltd. Between 2017-18 and 2021-22, while the government insisted that for-profit health care was not being expanded, the Don Mills Surgical Unit Ltd. saw its funding grow by 278 percent, according to the CCPA.

It’s the same story with nurses. Even as constrained hospital budgets make it difficult to fully staff up, private staffing agencies are doing a roaring business, says Mehra of the OHC. “They take staff out of the existing healthcare system and then sell them back to the health care system at enormous profit for themselves—often at twice, sometimes even three times, the cost,” she says. It’s not only expensive, it also creates a ruinous cycle: shortages of staff nurses make conditions in hospitals bad, leading to more nurses leaving the profession or defecting to agencies (where they make more money), making hospital conditions even worse.

Figures around expenditures on for-profit care are not easy to come by. Rates negotiated around surgical procedures, for instance, are not publicly disclosed. Even the total amounts transferred from the public purse to for-profit facilities is hard to discern. Longhurst found that, due a strange accounting practice, Ontario’s Public Accounts significantly underreport the amount of money the province transfers from the public coffers to for-profit entities. For instance, in 2021-22, Public Accounts reported that $65.8 million had been spent on for-profit care. But his Freedom of Information requests revealed that the number was actually $474.1 million—an underreporting of 720 percent.

For-profit providers don’t just cost the province more, either. They also cost individual patients more. For-profit clinics, the OHC found, often charge user fees and upsell medically unnecessary tests and services. Nothing in the law prohibits such upselling, says Longhurst—but it should.

Slowly but surely, the idea of private pay and for-profit provision is creeping into Ontario’s health system. A $9.99 fee for your for-profit diagnostic results here, a $25 fee for your hospital discharge notice there. Will it be $79.99 a month for virtual primary care, a $150 block fee for uninsured services from your family physician (who you can’t risk antagonizing because 2.5 million fellow Ontarians don’t even have one), or $5,000 to buy your way onto the roster of an OHIP-covered family physician working through a paid-membership-only clinic?

Bad as things seem, though, compared to other provinces, Ontario still has it pretty good, says Longhurst. We have a fairly well-integrated and coordinated hospital-based delivery system, he says, “which is how you deliver good surgical and diagnostic care.”

But he warns that the province is on a precipice. It could go the way of Alberta, he says, where it seems to be the political objective of the government to create so much chaos in the system that people start looking for alternatives. “If we have another Ford majority government, I fully expect things to ramp up further,” he says. “The government is moving in this direction. It’s shown no indication that it’s going to move away from building out a for-profit surgical and diagnostic sector.”

Local Journalism Matters.

We're able to produce impactful, award-winning journalism thanks to the generous support of readers. By supporting The Local, you're contributing to a new kind of journalism—in-depth, non-profit, from corners of Toronto too often overlooked.

SupportWhen a person enters an ER and waits hours in a chair, they may not immediately connect that to underfunding of home care or long-term care or supportive housing. They may not think about money being diverted to for-profit providers. But these things are, in fact, intimately connected. Nor would a patient necessarily realize that while they’re languishing in that chair, the ER staff, as well as handling emergencies, are also running what is essentially an in-patient hospital ward inside their emergency department. But they are. And just as conditions are getting worse and worse for patients, so too are they getting worse for staff.

ER wait times, numbers of patients in hallways, waitlists for long-term care, hours of available home care, numbers of Ontarians without family doctors, numbers of nursing positions unfilled, numbers of nursing staff hired through agencies—it’s all connected.

Adalsteinn Brown, dean of the Dalla Lana School of Public Health, was a member of the Premier’s Council on Improving Healthcare and Ending Hallway Medicine. I was curious how he felt things were going. When we met on Zoom, though, he wouldn’t be drawn on that. He pointed out that there’d been a pandemic—fair enough—but also that big health care system changes are notoriously challenging.

That said, he believes that there is no longer as much support for our model of health care as there once was, and we should be exploring how to do things differently. The answer is not simply more taxation, he says, but rather, we need to be more open-minded about different kinds of funding models and partnerships, including for-profit providers and even private equity. “I think a lot of stuff has to be on the table,” he says. But he admits it’s “complex.”

Irfan Dhalla, vice president of clinical programs, quality, equity and medical affairs at Unity Health Toronto (which comprises St Joseph’s Health Centre, St Michael’s Hospital, and Providence Healthcare), takes a different view. “The solution is relatively uncomplicated,” he told me. “It’s just expensive.”

He acknowledges there may be some complexity as to exactly how, for instance, something like home care is organized and paid for. And that there are more and less efficient ways of doing it. But the fundamental problem is an undisputed one: that there are hundreds of patients who have nowhere to go to be cared for, and even though they no longer need hospital care, if there’s no post-acute care available to them, the hospital is where they’re going to stay.

“Sometimes people look at the Netherlands or Denmark, and at some model of taking care of people in their own homes, or in small long-term care homes, or some other model, and they say, ‘Why don’t we have that here?’ And sometimes the answer is as straightforward as, ‘Well, we have chosen not to invest in that.'” Those other places pay more taxes, he says.

The reality is that health care is expensive, says Dhalla. We have agreed as a society that we will share the cost of things like intensive care, heart surgery, brain surgery, cancer treatment. “We don’t make people pay for that care if they need it,” he says. But if somebody needs five years of fairly extensive home care at the end of their lives, or if they need long-term care, we just don’t step up in the same way to fund that. Many people engage in magical thinking, he says, crossing their fingers that they’ll die peacefully in their sleep at age 80. The reality is likely to be otherwise.

It’s a choice, says Dhalla. “If there is a societal desire to really provide great care to everyone, we can do that. It’s a shared commitment that we all have to make,” he says. “It doesn’t have to be this way.”