Meghan could have rubbed shoulders with the greats. She was spending enough at her favourite online casino that it assigned her a staff member to share bonus offers, including events where she could hobnob with sports stars.

“I never actually went to those things, because part of me knew I would essentially be in a room with problematic gamblers because of the amount of money that we were dropping,” she said.

At the height of her gambling addiction, just a few days of banking transactions filled dozens of printed pages. Meghan estimates she gambled away $200,000 over the years. (The Local is identifying Meghan by first name only to protect her privacy.) Though gambling was a normal form of entertainment in her family, it took a different hold over her in 2020. Meghan’s mother died that year and she gambled online, even in the bathroom, to distract herself from grief and pandemic-era isolation.

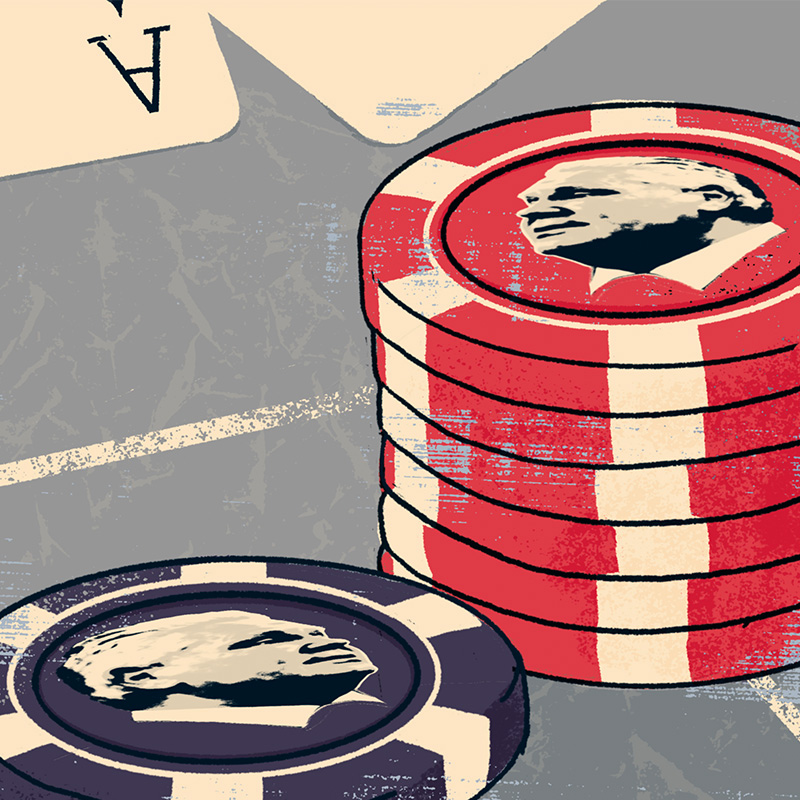

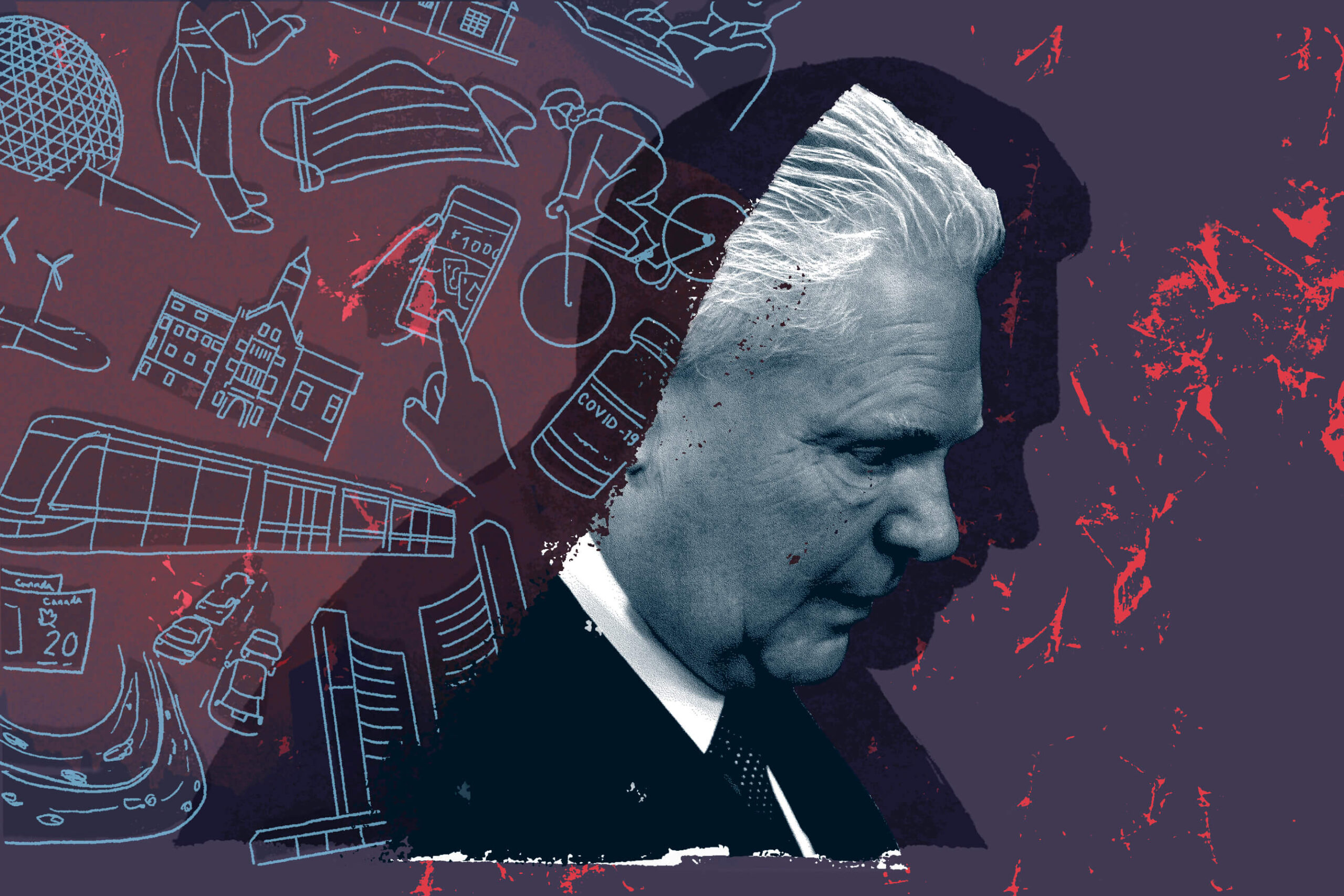

Two years later, one of the biggest shifts in the history of Canadian gambling took place in Ontario. First, following the legalization of single-sport betting nationwide, Ontarians could wager on a single game or outcome rather than needing to win parlay (or multi-outcome) bets. Alongside that change, Doug Ford’s Progressive Conservatives launched an online casino market unique in North America.

iGaming Ontario licensed private casino companies and allowed them to legally promote their services in the province, in exchange for agreeing to be regulated. This included mandated responsible gaming features and sharing a cut of revenues. The goal? Diverting spending from illegal or “grey market” online casinos, which are licensed in offshore jurisdictions. iGaming Ontario has grown to include more than 80 online casinos, including giants like BetMGM, DraftKings, and FanDuel. Twenty more await licensing. Operators litter social media, billboards, and media airwaves with advertisements and generate big business. Wayne Gretzky and Connor McDavid pitch bettors during hockey timeouts, instagram ads offer countless cash credits to lure-in first-time bettors, and gambling logos cover Ontario arenas, even during youth games. In fiscal 2023-24, iGaming wagers reached $63 billion and there were over 1.3 million player accounts in the year’s fourth quarter. Meghan was among them.

In Canada’s previous major wave of legalized gambling, Ontario was an early adopter, opening its first casino in 1994. But despite the growth of that industry, the province traditionally had lower rates of gambling problems than others. Now Ontario is among the top five North American online gambling markets. While a report prepared for the government expected the market to mature slowly over several years, it exploded out of the gate. A Deloitte consulting report, commissioned by iGaming Ontario, says the market’s economic contribution to Ontario’s GDP was equivalent to $2.7 billion in fiscal 2023-24. Those economic impacts are touted by the Ontario government as a win. But politicians aren’t as quick to discuss what Ontarians have lost.

The provincial Progressive Conservatives, Liberals, NDP, and Greens, all contacted through their press advisors by The Local, didn’t respond to requests to share gambling-related policy plans or election promises.

Meghan isn’t surprised. She’s written lengthy letters asking politicians to review gambling legislation, regulation, and what youth are taught about betting harms. “I’ve reached out to every representative you can possibly imagine, in addition to our local representatives, and no one wants to touch this.”

Join the thousands of Torontonians who've signed up for our free newsletter and get award-winning local journalism delivered to your inbox.

"*" indicates required fields

If the major political parties aren’t making gambling a campaign issue, it could be because the wider Ontario public isn’t thinking much about it either. Recent Nanos polling suggests health care is the top issue for nearly 30 percent of voters surveyed. But even though gambling touches on addiction and mental health supports, it’s not part of that conversation. “Gambling hasn’t been on the radar when we ask people what they are worried about,” Nik Nanos, chief data scientist and founder of Nanos Research, said over email. The economy and “dealing with US President Trump” were the only other issues to poll in double digits.

Ontario’s iGaming approach is a rarity in Canada. Though lottery crown corporations have operated legal gambling websites for years, including Ontario’s, the province is the only one to take a free market approach (Alberta may follow suit later this year). Operators pay 20 percent of their revenues to iGaming, but whether that’s a good deal is a matter of debate. Great Canadian Entertainment, one of the firms contracted to manage Ontario casinos—a dozen, including Toronto’s—commissioned a consultant’s report in 2022 that suggested Ontario could lose $550 million annually from gamblers pivoting to iGaming from land-based casinos, which pay 55 percent of their take to the government.

Besides the massive iGaming push, the Ford government has shown bullishness to expand gambling more generally. Last October, it announced a desire to increase physical casino offerings in Niagara Falls. There’s also a potential expansion of the iGaming sector looming. The Ontario Court of Appeal has been asked to rule on whether Ontarians can gamble alongside international players in a so-called “open liquidity” model. Presently, Ontarians are not legally permitted to mix with these wider pools of players. The shift could allow Ontario gamblers to play for bigger prizes, and is viewed by legal experts as a catalyst for further industry expansion.

If there’s one gambling-related issue that both politicians and the public are willing to touch, it’s advertising. A January 2023 Ipsos study, published only eight months after the launch of Ontario’s iGaming market, found 63 percent of Canadians agreed limits were needed for the volume and placement of gambling ads. An activist group called Ban Ads for Gambling took to the media, with Karl Subban, a retired Toronto school principal and father to three former NHL players, calling on Queen’s Park to make changes.

By summer 2023, four NDP MPPs, including Tom Rakocevic, the incumbent running in Humber River—Black Creek, introduced Bill 126, the Ban iGaming Advertising Act, which would have prohibited advertising by online gambling sites in Ontario. But the bill didn’t advance past a first reading, and died when the government dissolved. (Starting in Feb. 2024, the government restricted celebrity gambling endorsements in the province.)

Rakocevic said his constituents bring up gambling harms when he speaks with them. He recalls standing in the driveway of one, and noticing the man’s wife tensing up and crossing her arms, clearly anguished, as he spoke about his addiction.

During an affordability crisis, Rakocevic said, “gambling and the normalization of it is not helpful.” Rakocevic feels the new prominence of betting also affects how people view sports. “It’s almost like if you’re not doing it, you’re not part of the game,” he said. “I think it’s crossing the line.”

Those economic impacts are touted by the Ontario government as a win. But politicians aren’t as quick to discuss what Ontarians have lost.

While the iGaming regime is only three years old, and there have been few substantial studies of the effects of an open gambling market in Ontario, some community groups and experts are already worried.

Vince Pietropaolo is the general manager of family and mental health services at COSTI Immigrant Services, whose programs include counselling and outreach services for gambling. In his estimation, COSTI’s gambling-related clientele is “steady,” and sportsbetting has overtaken casino gambling as the primary issue. But the population his agency sees—immigrants and refugees, including newcomers—is often already at a “crisis point and they’re usually in debt” before reaching out.

He recalls parents approaching COSTI, concerned about their “withdrawn, highly irritable, agitated” 20-something son. The mother believed he was having trouble with his girlfriend or at his workplace. “There were issues in the relationship, but it was because he was absent,” Pietropaolo said. The man was focusing his attention on online gambling, his personality shifting as his debts frustrated him.

Cases like this, and a growing concern among parents he speaks with, have convinced Pietropaolo that more research is needed on early indicators of gambling addiction.

He also feels the province needs to do more to understand the prevalence and impact of gambling on the communities who visit COSTI, who can be vulnerable economically and potentially more susceptible to the myths of a big win as they build their Canadian dream. They also often have limited knowledge of what counseling is and how it works, and more stigma toward gambling than other Canadians. Many of COSTI’s clients are Muslim, he said, and these clients are among those seeking help for gambling, despite it being forbidden in their religion. For these clients to get there requires crossing a lot of psychological barriers, including embarrassment and shame, Pietropaolo said.

7 Years of Doug Ford

Like this story? Don't forget to check out the rest of the issue.

A Mental Health Research Canada study published in December 2024 estimated 16 percent of Ontario’s population is at medium and high risk of gambling addiction. That’s a significant increase over past studies, such as the 2018 Canadian Community Health Survey, which put that number at 2.9 percent in Ontario.

Matthew Young, chief research officer with GREO Evidence Insights, a non-profit research organization with expertise in gambling, thinks Canada’s gambling market was comparably “sustainable” for more than two decades, with gambling rates staying relatively steady.

The MHRC numbers place Ontario’s heightened gambling risks slightly above the 15 percent national average it reports. In the past, experts have suggested Ontario’s lack of video lottery terminals accounted for lower levels of problematic gambling than other provinces. That this gap might be closing due to the iGaming industry is a “viable hypothesis,” Young said.

In Ontario, Young notes that while the same regulators control alcohol, cannabis, and gambling, “we seem to be treating gambling very differently than all the other ones by allowing widespread promotion.” There are also few restrictions on availability. Bars, for instance, have closing hours. But Ontario now offers legalized gambling “24 hours a day, seven days a week, in the palm of your hand.”

The Ford government has focused on expanding commodities like iGaming or where alcohol is sold, but Young said these come with consequences—namely, extra harms to Ontario residents. “The tricky thing is, in this context, we don’t have a lot of data to suggest what that harm might be.”

Local Journalism Matters.

We're able to produce impactful, award-winning journalism thanks to the generous support of readers. By supporting The Local, you're contributing to a new kind of journalism—in-depth, non-profit, from corners of Toronto too often overlooked.

SupportEach of the three parties which have governed Ontario since 1993 has undertaken gambling expansion on some level. And historically, legalized gambling grows in moments of economic challenges. All of that suggests that, no matter who wins this provincial election, the growth of legalized gambling will continue in Ontario—an unprecedented wager whose repercussions we won’t understand for years to come.

For her part, Meghan is committed to pushing the conversation about the risks of gambling to the forefront. As part of her recovery, she’s made a point of sharing her story and volunteering with organizations to help teach others about the challenges gambling can create. She hasn’t placed a bet since Aug. 9, 2024.

Though she grew up in Ontario as it underwent the wave of casino building that normalized and destigmatized gambling culture, her son is growing up during the current era, which has an arguably greater hold over the public imagination.

She considers him “lucky” because of what she’s been through. “I know how to teach him,” she said of gambling addiction. “I know how to have those conversations.”

She’s less confident in a broader dialogue—at least for now. “We don’t know how to handle it.”