On January 22, 2012, Ahmed Sualim, a 19-year-old man from Toronto, walked into a convenience store in the Caledonia-Fairbank neighbourhood, pointed a silver revolver at the cashier, and left with $200. Four days later, Sualim held up an Esso station. Three days after that, he ran off with a diamond ring from a Peoples Jewellers in Scarborough.

The stickups quickly escalated, becoming more frequent and brazen. By the time he was arrested on February 1, he had stolen $80,000 worth of cash and jewels in ten separate incidents. The cops had fingerprints and video surveillance linking him to the crimes. In the fall of 2014, a judge sentenced Sualim to over five years in jail.

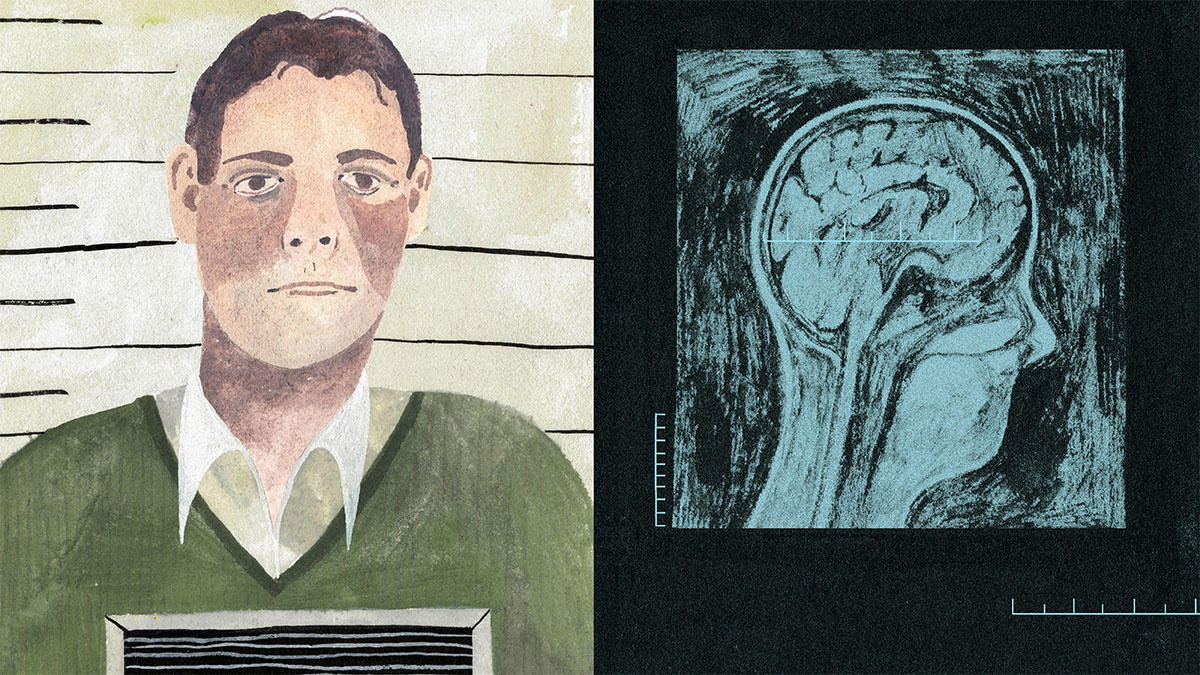

While the trial was relatively straightforward, the story was more ethically complicated than it initially appeared. For a long time, Sualim had been mentally unwell. During his adolescence, he’d spent hours talking to himself in the bathroom mirror. He’d warned his family that nefarious forces were plotting to bomb their home and complained about recurrent headaches, which he attributed to a chip having been implanted in his brain. Throughout the week of the crimes, he’d listened repeatedly to the song “Otis” by Jay-Z and Kanye West, and believed that there was a message for him embedded in the lyrics. “I was hearing voices saying rob,” he told a clinician, “but Jay-Z said it was okay, that I would not be in trouble.”

In 2017, Sualim’s lawyers appealed his conviction, arguing that at the time of the robberies he’d been in the grips of a psychotic episode. They hoped to overturn the guilty verdict and have it replaced with a designation of “not criminally responsible.” An NCR ruling doesn’t render a person innocent. Rather, it specifies that the defendant committed the crimes in question but cannot be deemed criminally accountable, because they were not mentally capable at the time of making ethical choices. NCR patients are transferred from the criminal justice system to the health care system, which has an entire field, called forensic psychiatry, devoted to their recovery.

Sualim won his appeal and was later given NCR status. In the summer of 2018, he was brought to the forensic ward at the Centre for Addiction and Mental Health (CAMH), Canada’s largest psychiatric hospital, where he was to be confined until doctors determined that he no longer presented a public risk.

Sualim’s crimes—a series of mid-level robberies, followed by a speedy arrest—were always of limited interest, and the story would have disappeared from the public record had it not been for a series of events last summer that had little to do with him. First, in early June, Kleiton Da Silva, who’d been given NCR status after killing a man in a street brawl, went missing from CAMH and allegedly robbed a bakery. A month later, Zhebin Cong, who’d been found NCR for stabbing a man to death in a boarding house, went AWOL and then fled the country. In late July, Sualim also left CAMH under the supervision of a hospital staff member and then walked off on his own.

Because Sualim’s disappearance happened so shortly after the more dramatic incidents involving Da Silva and Cong, it got folded into the media narrative. Outlets reported that CAMH had seen a spate of “escapes” in two months. Pundits wrote panicked op-eds about the threat to public safety. In a radio interview, Ontario Premier Doug Ford referred to NCR patients as “animals.” “We’ve got to put these people away,” he later argued, “and if they have mental health issues they can be dealt with in jail—simple as that.”

The Globe and Mail recently revealed that at CAMH disappearances like Sualim’s happened more than 300 times in the last decade and as many as 43 times per year. Other forensic facilities in Canada may have slightly higher or lower rates, but such incidents occur everywhere. When confronted with such data, it’s hard not to instinctively agree with Premier Ford that the system is failing. But, a closer look shows that the opposite is true. The fact that NCR patients sometimes go missing is evidence that a complex, responsible system is working well.

The notion that certain people should be exempt from criminal liability due to their mental state is as old as jurisprudence itself. Variations of this idea show up in the ancient Code of Hammurabi. In English Common Law, the pivotal case is that of Daniel M’Naghten, a Scottish woodturner who in 1843 shot and killed Edward Drummond, secretary to the prime minister. At the Old Bailey courthouse in London, a jury declined to convict M’Naghten, who was clearly suffering from paranoid delusions. Later that year, a panel of twelve judges established the M’Naghten rule—also referred to as the insanity defence—stipulating that a person cannot be convicted if, at the time of the offence in question, they were unable either to appreciate the nature of their actions or to tell right from wrong. In 1892, the M’Naghten rule was incorporated into the Canadian criminal code.

A successful insanity defence was the furthest thing from a get-out-of-jail-free pass. Any Canadian found not guilty by reason of insanity would then be held indefinitely—often in a dark, squalid psychiatric ward—until the lieutenant governor of their province decided to set them free. The terms of confinement were so severe that in some trials the Crown actually invoked the M’Naghten rule against the defendant’s wishes. The fact that prosecutors would plead the insanity defence raises questions as to whether it was a defence at all.

In 1991, the Supreme Court of Canada struck down the laws. It ruled against the principle of automatic detention, the clause stipulating that all people acquitted under the M’Naghten rule must be confined in a hospital. It also ruled that defendants should be allowed to decide for themselves whether to plead insanity at trial; the Crown would no longer be permitted to override their choices. A year later, the Mulroney government passed a bill replacing the insanity defence with the concept of NCR. Instead of being detained at the pleasure of the lieutenant governor, people found NCR would be subject to a provincial review board, which would make case-by-case decisions.

In legal proceedings today, shortly after a new NCR verdict is reached, the patient is granted a review-board hearing before a panel of lawyers and medical professionals. These hearings are invariably tricky. “The Canadian criminal code views people as having rights of liberty that can only be curtailed as much as necessary,” says Sandy Simpson, chief of forensic psychiatry at CAMH. The board is tasked, he explains, with giving each patient the maximum amount of freedom while at the same time keeping the public safe. “There’s an obvious tension going on there.”

“You can’t let guys like this loose,” Premier Ford said. “You throw away the key.”

When making its determinations, the board chooses from a range of options, from confinement in a psychiatric institution, to a supervised living arrangement outside the hospital, to an unconditional discharge. Except, in the latter case, the decisions aren’t final. People found NCR are entitled to a new hearing each year, at which point the board considers new information about the patient’s health and updates its decisions. The amount of time each patient stays in the system depends on their recovery. Some people are swiftly discharged; others remain confined for life. “It’s a process, not a timeline,” says Simpson.

While the review board makes annual, high-level decisions, it falls to doctors and other hospital staff to make the more granular, week-by-week assessments. They may start by severely limiting a patient’s movements, permitting him only to visit an enclosed exercise yard under supervision. From there, he may be allowed to briefly leave the hospital in the company of a staff member. If that goes well, he could finally get a day pass and head out for an afternoon on his own. If he handles each new freedom responsibly, he gets a bit more freedom. If he handles it poorly, he gets less. Every privilege is also a test.

But for a test to be meaningful, there must be a reasonable chance of failure. Psychiatry is a branch of medicine and, in a responsible medical system, some degree of failure is necessary because it demonstrates a healthy tolerance for risk. And while the new NCR system is more humane than the one it replaced, it isn’t exactly lenient. In many cases, patients spend more time confined than they would had they simply been convicted and sent to prison. “NCR finds you not criminally responsible, but it doesn’t find you unaccountable,” says Simpson. “You’re accountable for your wellness and your safe recovery going forward.”

The West 5th Campus at St. Joseph’s Healthcare in Hamilton, Ontario, is a sprawling compound opened in 2014, in which clinicians treat everything from mood disorders to dementia. It also includes a medium-security forensic unit with 114 beds. Unlike the building it replaced—a grim, sunless ward from the 1870s, where people sometimes slept four to a cell—the centre has seventeen courtyards, which bring natural light into each patient’s en suite room. The central hub of the forensic unit has a kind of Main Street vibe, with a barber shop, a used clothing store, and a canteen with old vinyl albums tacked to the walls.

I recently met Gary Chaimowitz, the head of forensic psychiatry at St. Joseph’s, for a tour of the facility. He is a talkative, bespectacled man with an accent that betrays his South African origins. By virtue of his position, Chaimowitz has become something of a spokesperson for the NCR system: if you run a forensic unit, where your job is to reintegrate and release patients into the world, you will inevitably be called upon to defend what you do.

He argues that the forensic process, with its escalating passes and privileges, is best understood by analogy to parole in criminal justice. Just as the parole boards seek to acclimatize inmates to the outside world—instead of just releasing them after time served—the forensic system progressively reintegrates patients into society, all the while monitoring their mental health. If the various passes and privileges are tests, meant to assess how well a patient handles each new freedom, they are also opportunities: they allow patients to take classes, attend job interviews, search for housing, and build up the social scaffolding that sustains a human life.

Unlike criminal justice, however, forensics is intended to be restorative, not punitive. “We can actually treat the psychosis,” says Chaimowitz, “the very thing that led to the criminal act.” While there is no medical cure for ordinary criminality, patients with bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, and schizoaffective disorders really do respond to treatment.

This fact helps explain why recidivism among NCR patients is much lower than it is among former prison inmates. Roughly 34 percent of people released from jail in Canada go on to reoffend within three years. Among NCR patients, that number is 17 percent, and if you select for serious offences, like murder, attempted murder, and sexual assault, the rate drops to 0.6 percent. NCR patients who initially committed such extreme crimes are actually among the least likely to reoffend. “The medications we use for psychosis are like miracle drugs,” says Chaimowitz. “People get their humanity back.”

When the story of the Da Silva, Cong, and Sualim AWOLs hit the news last summer, CAMH went into crisis-management mode. They’d had a good run, with significantly fewer disappearances than in previous years. In Canada, virtually all AWOL patients are located, typically hours after they leave the hospital and, in the twenty-five years prior to Da Silva’s robbery, only one CAMH patient had committed a crime while missing (He’d thrown a pop can at a police officer). But, as far as the public was concerned, the numbers didn’t matter. Da Silva had been charged with robbing a bakery, Cong had fled the country, and now Sualim had walked off, too. Suddenly, pundits and social media users were expressing fear of the entire forensic program.

Rather than telling Canadians what they should or shouldn’t worry about, Simpson is working to restore faith in what he and his colleagues do. “Patients rehabilitate in the space the public, the media, and politicians give them,” he says. In the wake of the media firestorm, the hospital temporarily clamped down on day passes and struck an external panel to review the entire process by which such privileges are granted. This decision may have been politically necessary, but it didn’t make life easier for people confined at CAMH.

Last September, I attended an Ontario Review Board hearing for a CAMH patient named Christopher Collins. In 2005, Collins had been arrested for a relatively minor crime: he’d planted a knife in his neighbour’s front door. Since being found NCR, he’d resided in both hospitals and community living facilities, and he’d committed a number of additional offences, including an assault on his father and several fist fights with fellow patients. But Collins was now recovering. Although he still smoked too much marijuana (this was the reason for his readmission to hospital last July), he hadn’t otherwise misbehaved in the past three years.

“We’ve made a lot of progress in dispelling myths about the perceived dangerousness of people with mental disorders. All it took was one moment in time to completely turn back the clock.”

At the hearing, Collins sat at a boardroom table in a CAMH meeting room. He was flanked by his lawyer, Anita Szigeti, and a hospital psychiatrist, Paul Benassi. At the opposite side of the table, peering at Collins above notepads and laptops, was a panel of five older men, all of them legal or medical professionals, who would determine his fate for the coming year. Within this buttoned-down atmosphere, Collins stood out. A heavyset man with close-cropped hair, he wore an oversized T-shirt and a bright steel wristwatch—surely the most noticeable fashion accessory in the room. During much of the hearing, he looked down at the table in front of him, avoiding eye contact with his interlocutors.

Benassi testified about the recovery Collins had made and expressed his view that the patient should be granted a wide range of privileges, including the right to potentially leave the hospital and move in with his mother. The proceeding, with its convivial tone, lacked the adversarial spirit one normally encounters in courtroom settings.

This changed, however, when Szigeti was invited to cross-examine Benassi. She started by asking the doctor if he was aware that CAMH patients had a bill of rights, one that entitled them to fresh air every day. After Benassi answered in the affirmative, she inquired as to why Collins had been denied fresh air for nine consecutive days following his readmission to hospital earlier that summer. Benassi responded delicately: “Mr. Collins was admitted to CAMH at a time of significant scrutiny in the media that had caused CAMH to review its procedures for granting privileges.” In the messy aftermath of the AWOL controversy, Collins’s basic request to visit the exercise yard had been held up.

Collins had accepted this misfortune with equanimity. He’d even joked with a hospital employee that he’d picked “the worst possible time to be readmitted.” Still, it was hard to not feel sorry for him. Fresh air is hardly an extravagant luxury, and nine days is a brutal length of time to go without it. Clearly, Collins had been penalized for mistakes that weren’t his. “I’m shocked by the immediate effect that the media-driven hysteria around those AWOLs has had,” Szigeti said, after the hearing. “Over the last few decades, we’ve made a lot of progress in dispelling myths about the perceived dangerousness of people with mental disorders. All it took was one moment in time to completely turn back the clock.”

If we are to permit NCR patients the space they need to recover, we must accept that sometimes AWOLs happen. The forensic system is constitutionally obliged to give people a fair shot at freedom, which means patients must be able to demonstrate, to both doctors and the review board, that they are capable of behaving responsibly outside the hospital walls. But they’ll never get to make that case if they aren’t allowed to try. The forensic program isn’t immune to failure, but in a functioning health care system, some degree of failure is necessary. Surgeons, emergency-room doctors, and other high-stakes medical professionals take calculated risks all the time. Often, it’s the most responsible thing to do.

After the incidents last summer, Premier Ford spoke of his partiality for more extreme measures. “You can’t let guys like this loose,” he said, of forensic patients. “You throw away the key.” For constitutional reasons, Ford’s preferred remedy will never become law. But it’s worth contemplating, if only as a thought experiment, what life would be like if it did. Imagine a world in which people who’ve committed crimes while mentally unwell are given automatic life sentences without even temporary access to the wider community. The good news is that, in this alternate universe, the crime rate would be slightly lower than it currently is. The bad news is that everybody has the potential to become mentally ill, which means all people—including you and those you love—would be subject to indefinite detention with no opportunities for recovery, rehabilitation, or growth.

A less terrifying world would look like the one we currently inhabit, in which the health care system accepts that illness is a fact of life and responds with generosity and a tolerance for risk. Granted, the overall risk is vanishingly low—recall that, since the mid 90s, only two CAMH patients have been charged with crimes while AWOL—but it isn’t zero. In health care, it rarely is.

For all the media hype around Sualim’s disappearance last summer, one part of the story—the ending—received little public attention. The resolution is dull, but its very banality makes it representative of how these incidents typically play out. A few hours after Sualim went missing, his mother helped locate him at the house of a friend. When hospital staff approached Sualim, he didn’t put up a fight. Rather, he did what people in his situation almost always do—he gathered his belongings and went home to CAMH.