On Sept. 3, the first day of class, lone freshmen wander the halls of York University’s Markham Campus. First opened in November of 2024 in a developing corner of downtown Markham near the Unionville GO station and Highway 407, the campus is a building clad in glass and bronze-coloured panels rising from a sea of parking. At 10 storeys and 400,000 square feet, it is designed to accommodate 4,000 enrolled students. As of this September, enrollment was roughly a quarter of that.

In the cafeteria, a single café owned by the university serves the entire campus. It’s the middle of the lunch rush and a dozen students sit scattered among nearly two dozen tables, whispering so their voices don’t echo too loudly against the gleaming tiles and high ceilings. Class lets out, and about 50 students briefly flood the space. Outside, a student picks up a food delivery order before scurrying back inside. Within minutes, the din of voices dissipates, and the halls are quiet once again.

At $280.5 million, Markham Campus is York University’s most expensive capital project to date. First proposed in 2014, it was met with intense pushback from the York community, who decried the expense in the face of other financial pressures—a growing backlog of repairs to the university’s other two campuses in Toronto, increasing reliance on contract faculty and staff, the slimming down of opportunities for tenure, and a litany of other concerns about working conditions at the university. To add salt to the wound, a promise made by the province to kick in $127 million was cancelled by Premier Doug Ford upon his election in 2018. That same year, the Ford government used back-to-work legislation to end a strike by contract faculty and teaching assistants at York that had lasted 143 days—the longest strike in Canadian post-secondary history.

I (Sabika Zaidi, the co-author of this piece) joined York University as an international student to pursue a masters degree shortly after. I was drawn to York for the same reason so many are—to learn in a rich tradition of critical research in the social sciences and humanities. However, it quickly became apparent that the strike had lingering effects, with a pervasive sense of bitterness between colleagues and the administration. At this point, the larger York community came together to organize events aimed at rebuilding trust among students, admin, and teaching staff, including a harvest party to distribute produce from a community garden that was started on the picket line.

One of the first meetings I attended on campus was to consult on the future of Markham campus. For my fellow graduate students and faculty, it felt absurd to be spending hundreds of millions on a shiny new building so far from the city when we were learning and teaching in crowded classrooms in buildings that felt like they were falling apart.

Despite the loss of provincial funding, however, York pushed ahead with the development of Markham Campus, securing funding from York Region and the City of Markham, in addition to money from donors and its own capital funds. In July 2020, during a press conference announcing the imminent construction of the campus, Doug Ford praised the project.

“Instead of the province writing multi-million dollar cheques, we have developed a system that encourages the development of new campuses with a much smaller cost to the taxpayer,” Ford said at the time. “The new Markham Centre Campus is a model of responsible expansion.”

Three years later, the Office of the Auditor General of Ontario released a report on York University. Addressing seven major capital projects the university had taken on, including Markham Campus, the Auditor General found that “York did not prepare full business cases for capital projects before proceeding with them, including fully assessing the financial viability of those projects.”

One of the calculations the university had failed to do, according to the Auditor General, was to estimate when it would recover its initial investment in Markham Campus. The Auditor General estimated it would take until 2038-39. Meanwhile, the report found the deferred maintenance backlog at York’s Keele and Glendon campuses had ballooned. Between 2019 and 2023 the backlog more than doubled, from $459 million to $1.04 billion, leaving them in a “state of critical disrepair,” according to the report.

“You’re just putting out fires all day,” says Joseph, a maintenance worker at Keele Campus whose name has been changed for fear of professional reprisal. “Instead of repairing or replacing [old air conditioners] and heating units after 50 to 60 years in service, you’re putting a Band-Aid on them to get them going for a week, two weeks, a month.”

Still, York’s capital commitments consumed a much larger share of their budget than repairs.

Altogether, the Auditor General said, York had “directed substantially more resources toward constructing new capital buildings and expansion projects—$745.3 million over the past five fiscal years compared to $94.7 million on deferred maintenance.”

For some at York, the Markham Campus saga is emblematic of relations between senior administration and the York University community in recent years: major decisions are made despite outcry from students, faculty, and staff, and it is them who are left to bear the consequences—or leave altogether.

Join the thousands of Torontonians who've signed up for our free newsletter and get award-winning local journalism delivered to your inbox.

"*" indicates required fields

The problems faced by York University, like many other universities in Ontario, should be understood first and foremost as a failure of successive provincial governments to invest in post-secondary education.

According to a November 2023 report by the Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives, the province provided 78 percent of operating revenues for Ontario’s universities in 1987-88. By 2001, this had dropped to 36 percent. In 2022, universities got less than a quarter of their operating revenue from the provincial government.

While this mirrors trends across the country, Ontario has the lowest per-student funding of any province in Canada. A freeze on domestic tuition by the Ford government in 2019 continues to this day, cinching the budgetary belt ever tighter. Like many universities, York also spent the past decade aggressively pursuing international student enrollment. (According to the 2023 Auditor General’s report, international students made up 18 percent of York’s student body, and nearly half of their tuition revenue.) When the federal government curtailed international student enrollments in 2024, it effectively hamstrung the university’s budget.

Ostensibly as a result of these constraints, York has been slimming down its employee ranks. In 2024-25 alone, 173 administrative employees and 29 faculty members accepted voluntary buyouts to leave the university. According to a statement from York, these are expected to yield about $40 million in savings in total by 2028. This fall, the university “temporarily paused” admissions to 18 programs, including heavyweights in the humanities such as classics and English, alongside equity-focused programs such as Indigenous studies, Jewish studies, and East Asian studies.

“All of these measures are intended to put the university on solid financial footing,” York spokesperson Yanni Dagonas wrote in a statement to The Local. “We understand that addressing these challenges can create feelings of uncertainty and anxiety, and we are determined to ensure our actions are transparent.”

However, in conversations with representatives from three of York’s unions, they say it is precisely a lack of transparency around these decisions that stings. In 2023, when I served on the bargaining team for CUPE 3903—the union representing contract faculty, teaching assistants, and graduate assistants—this remained a sticking point in conversations between the union and the university.

“It’s not as if people don’t understand that there’s a financial crisis,” says Arthur Redding, a professor of English at York who currently sits on the executive committee of the York University Faculty Association (YUFA). “But as students, staff, faculty, sessional instructors, we would want to be participating in the decision-making process about what the future looks like.”

Aside from Markham Campus, YUFA says a number of major decisions over the years were made without adequate consultation from the York community. These include the decision to return to in-person learning after the COVID-19 lockdowns, the decision to make meetings by the executive branch of the Senate confidential, and the decision to pause admissions to those 18 programs.

In March, YUFA applied for a judicial review of these enrollment suspensions.

In addition to a perceived lack of community consultation—which was echoed by the other union representatives we spoke to for this article—YUFA says the fissure between the York community and its senior administration can be seen in the increasingly fractious state of labour relations since 2019.

When employees have a problem with their working conditions, they file a grievance with the university through their union. Traditionally, minor grievances were settled relatively quickly. More intractable cases were sent to arbitration, a lengthy legal process where a third-party arbitrator hashes out the case with lawyers on both sides.

After 2019, however, Redding says even minor grievances became contentious. York’s approach became “not to negotiate anything,” he says. “So even small disputes which should be easily resolved always end up going to arbitration. This costs our union boatloads of money in legal defenses.”

In an email to The Local, York spokesperson Yanni Dagonas wrote that the statement that “York does not negotiate anything” is “patently false.”

“The University’s preference is that grievances be resolved as early in the process as possible. Dispute resolution commonly requires compromise on the part of both parties. Where the parties are unable to find a mutually agreeable solution, the Union may decide to proceed to arbitration,” he wrote.

But York does not dispute that the number of grievances has gone up. “The University can confirm that YUFA has increased its filing of grievances since 2023-2024 after the university initiated a number of responsible measures to address financial sustainability issues,” wrote Dagonas.

The reasons for these grievances, according to Ellie Perkins, a professor in the faculty of environmental and urban change and the current president of YUFA, range from increased class sizes to the cancellation of courses to issues around academic freedom. They also include cases where she says instructors are being made to teach two classes simultaneously, in the same classroom. (In response to a question about the feasibility of doing this, York spokesperson Yanni Dagonas wrote: “this circumstance is referred to as ‘taught with’ and reflects an established and longstanding teaching arrangement that has been in place over multiple academic years.)

Not all of these grievances end up in arbitration, but those that do incur a heavy financial cost. YUFA’s budget shows they spent $822,334 on arbitration in 2023-24. It’s not clear how much York is spending on their end.

The heaviest burden of this fractious and prolonged process, however, is not borne by the university or even the unions at York, but by the workers whose disputes go unresolved for months, sometimes even years.

In just one example from CUPE 3903, a teaching assistant experiencing a health crisis applied for a medical leave from their studies. As per their contract, they had a right to complete their teaching assistantship—the main source of income for many graduate students. According to a CUPE 3903 website post this past April, York refused.

The arbitration process took three and a half years, and cost their union tens of thousands of dollars, but in the end, they won. By that time, however, the damage had already been done. The student lost access to their income and health benefits in the middle of a health crisis. (“Disagreements over collective agreement interpretation occur,” wrote Yanni Dagonas. When parties can’t reach a shared understanding, he wrote, “an arbitration award can provide clarity.”)

This arbitration-first approach to labour relations, says Redding, has “institutional consequences, it has human consequences. It struck me as a deliberate shift in strategy that I saw between the time I was chief steward and the time I resigned as president. We could no longer work things out.”

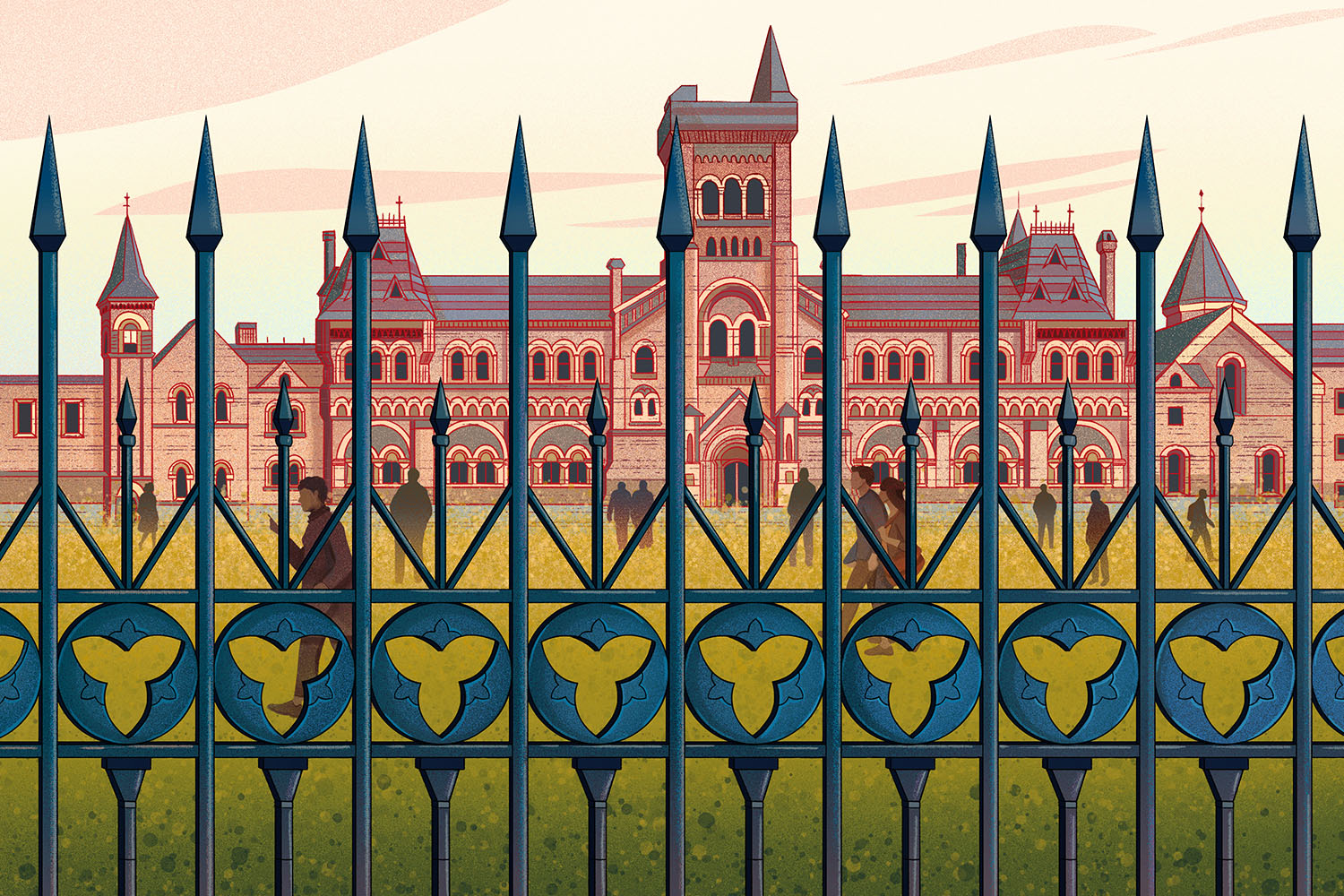

The current fissure at York University between the community and senior administration is rooted in a more fundamental tension. Since its inception nearly 66 years ago, York has been shaped by the struggle to balance its foundational mission to provide students from disadvantaged backgrounds with a world-class experience of higher education with pressure to compete with other institutions for resources and talent.

Its first president, Murray G. Ross, was a principal founder of York, and the university’s operations began on the University of Toronto’s downtown campus. The aim was to create an alternative to Canada’s large universities that would meet the demands of a growing and diverse population in a holistic way, according to Michiel Horn’s York University: The Way Must Be Tried.

However, the population boom of the late 20th century was upon them. By the end of the 1960s, with the addition of the Glendon and Keele campuses, York had grown from a handful of students to more than 15,000, with legions of faculty and administrators to support them.

All of this expansion did not come without growing pains.

The first major labour unrest at York happened in 1970, after Ross retired. A power struggle ensued between the Board of Governors and the Senate over York’s new president, according Horn. The eventual appointee, David Slater, recommended faculty layoffs to offset a $4-million shortfall in 1972 due to lower-than-expected enrollment. The backlash he faced was so intense, he resigned.

The torrent of bad press that followed the episode gave York a reputation that would eventually stick: as an institution prone to internal strife. For faculty, staff, and student-workers, it would mark the first major moment where they felt cut out of decisions that directly impacted their livelihoods.

By the early 1990s, Ross’s dream of a modest liberal arts college had all but vanished. York was now a juggernaut of 40,000 students, and would become the largest university in the country outside of U of T. But its focus on the liberal arts had made it a formidable source of research in the social sciences and humanities, and it had retained an outsized interest in these fields. A report published in 1992 by a working group at York considered the question of the university’s future. It was titled “Vision, 2020.”

The biggest question they faced was whether to expand the university’s course offerings in fields like STEM and health sciences. Doing so would mean even more expansion: an engineering centre, a life sciences building, and ever-more student housing and amenities. But it would also mean a shift in focus from the areas that had made the university distinct in the first place.

Regardless, the document argued, York had no choice but to expand in this direction. If students wanted to study health sciences and STEM, then they had a responsibility to meet that demand. Otherwise, they would be shortchanging their target demographic—students from the working-class communities of Toronto’s inner and outer suburbs. These students would lose opportunities to study close to home.

At the same time, it cautioned that expansion could easily come at the cost of the quality of education and community life that the university so prided itself on.

“Is there a particular size of the university which would take us past critical points at which the quality of academic and community life would be jeopardized?” it asked. “History has answered that question already. We are committed to being a large metropolitan university.”

Local Journalism Matters.

We're able to produce impactful, award-winning journalism thanks to the generous support of readers. By supporting The Local, you're contributing to a new kind of journalism—in-depth, non-profit, from corners of Toronto too often overlooked.

SupportToday, the university whose campuses were once considered remote is now almost central to the sprawling suburban landscape of the Greater Toronto Area. Waves of immigration to Toronto, and the neighborhoods west of Keele Campus in particular, have brought generations of racialized, immigrant students to York, in that same search for a world-class education away from the perceived cold snobbery of U of T.

While the next wave of those students may still find a spot at York University, it is probable they will walk into a dirtier and more crowded classroom and have less face-time with their professors.

Some of these cracks had already begun to appear when I returned to York in 2022 to pursue a PhD. As teaching assistants, my colleagues and I were forced to do more with less. The ratio of TAs to students almost doubled in my classes, students received less feedback on their assignments and fewer assignments altogether, and the use of AI in classrooms increased, with York guidelines leaving the responsibility for figuring out the limits of AI use to course directors. As funding and wages failed to keep up with the times, it became clear to me (and many others in a similar position) that constant precarity was part and parcel of pursuing higher education at York. After a personal loss in the family, I withdrew from the PhD program to pursue work opportunities elsewhere.

Meanwhile, York is in the midst of another major capital project: a new medical school set to open in 2028. At the same time, earlier this summer, President Rhonda Lenton announced she will resign her post 18 months early. Lenton leaves behind a complicated legacy. Under her tenure Markham Campus was built and senior administrative ranks ballooned nearly 40 percent, while the maintenance backlog exploded and programs were slashed.

“She’s deciding to step out from her position without fixing anything that she has caused,” says Somar Abuaziza, the president of the York Federation of Students (YFS), the union representing the 50,000 undergraduates.

Between funding cuts, a harrowing job market for youth, the knock-on impacts of the pandemic, and the steep cost of living, she says more students are accessing the union’s resources than ever. The student union’s job, Abuaziza says, “has turned from supporting the students and providing them with services to filling the gaps of the administration.”

YFS runs an academic support centre, a wellness centre, and a food support centre, among other services. But the university’s dip in enrollment has meant fewer union dues, meaning they, too, have to do more with less.

“We’re working so hard and ensuring that we keep everything the way students need,” she says, instead of cutting down services. “We’re not like the administration.”