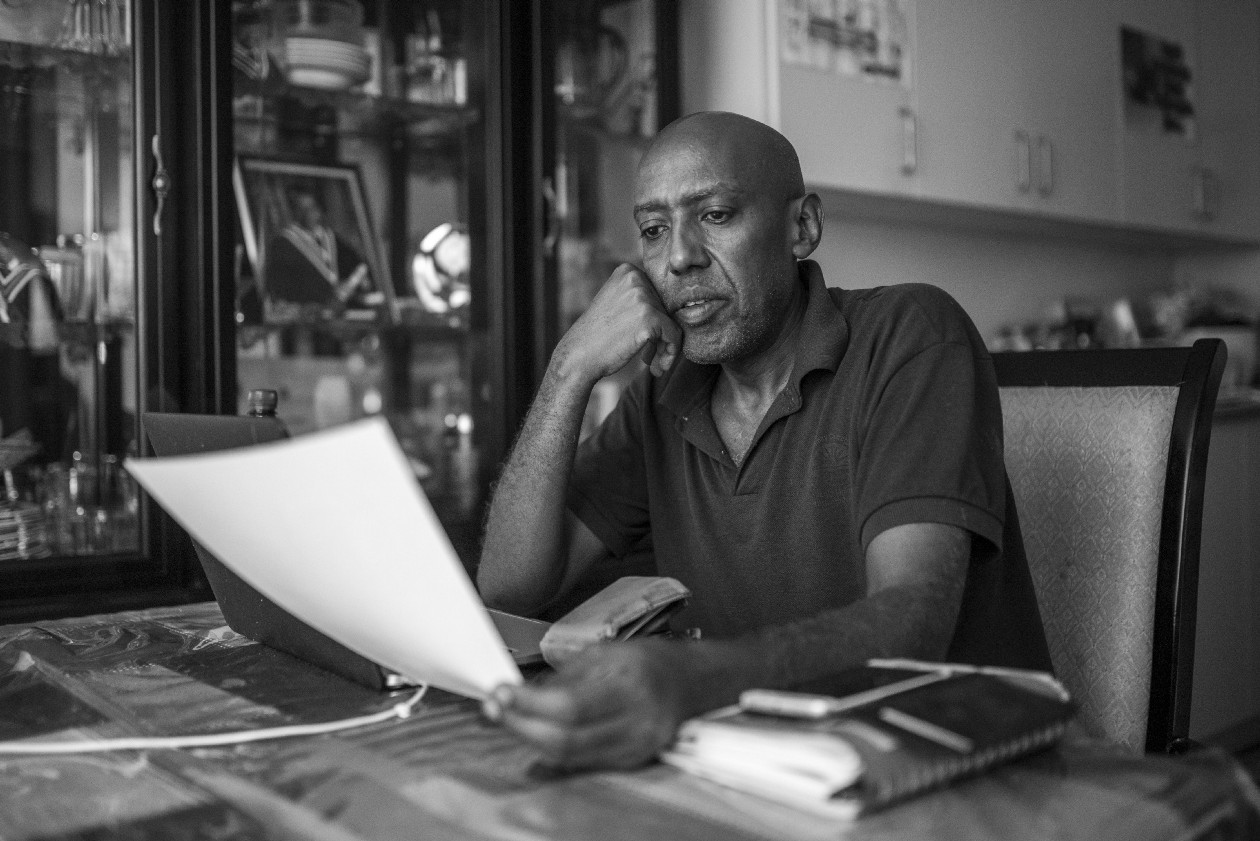

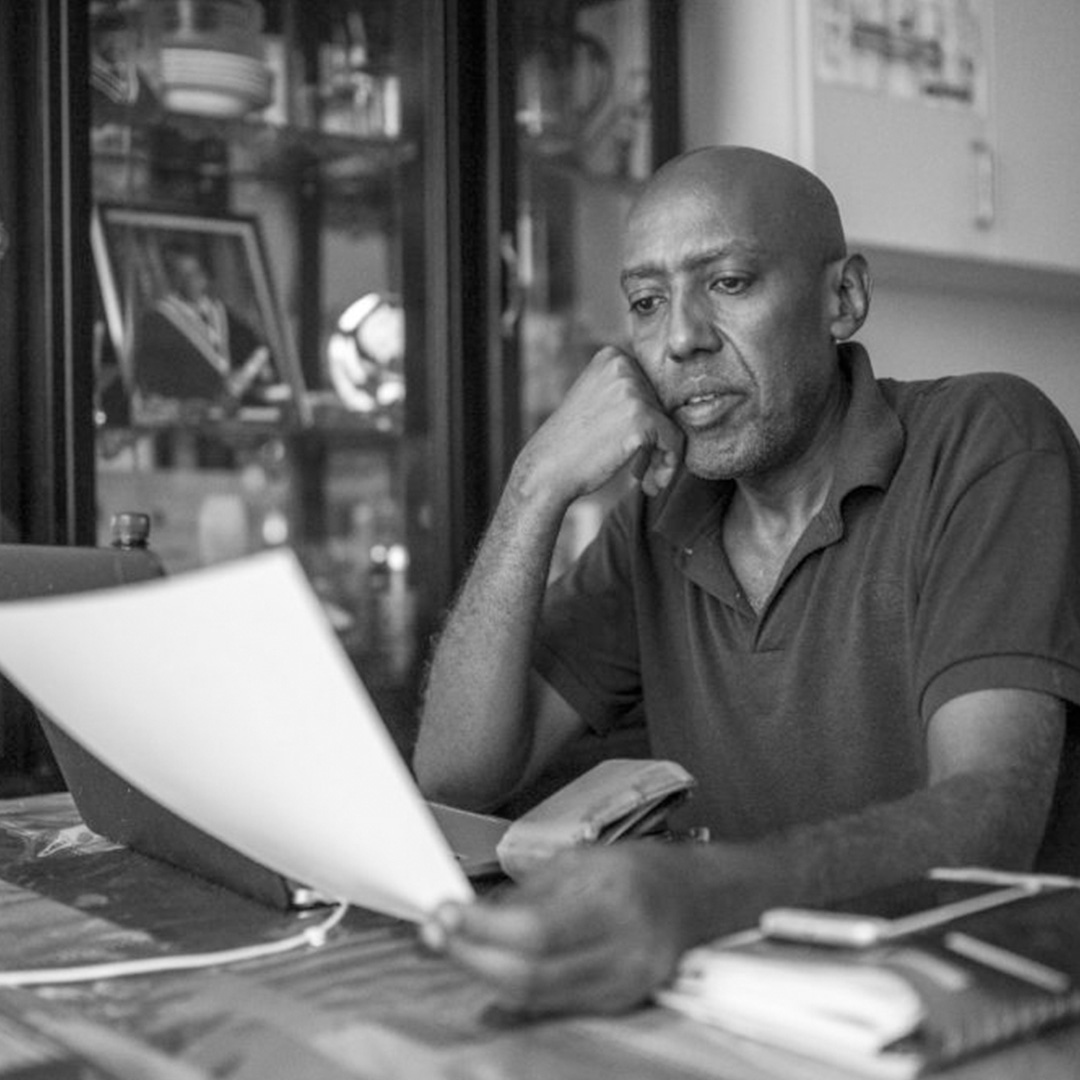

On a hot Monday in July, Ghirmai Abraha was hustling through the city. The soft-spoken interpreter, a lanky 54-year-old with a calming demeanour, is used to being busy. The life of a freelance interpreter means living your life on call — waiting by the phone to be summoned by the Canadian Service Border Agency or a family health clinic, Toronto Court Services or a host of other agencies across Canada and the US. It means keeping your life in a well-worn planner, stuffed with envelopes and dog-eared from daily use. “I go whenever they call me,” says Abraha. “I go outside of Toronto, I go to Brampton, I go to Kitchener, I go to Hamilton, to the border areas in Fort Erie and Buffalo.”

That morning, Abraha had an assignment at the Christie Refugee Centre. The client was a young woman who had just moved from a shelter. “She has a lot of things that she has to deal with it,” he says. After working with her and her settlement worker for an hour, Abraha rushed to his Toyota parked out front and got on the phone with Immigration and Citizenship in Winnipeg. For the next two and a half hours he sat in his car, parked on the street, interpreting for three Ethiopian immigrants attempting to navigate the Canadian border system.

Abraha’s life as an interpreter is a long way away from the career he thought he’d have. He was born in Eritrea, the small country just north of Ethiopia. In 1988, he graduated university with a degree in mechanical engineering and began working for the Ethiopian government. He was building a comfortable life for himself when the Ethiopian-Eritrean war broke out in 1998. That year he was called for military conscription. “It was devastating,” he reflects, his head hanging low as he’s pulled back to the moment. “It was a very bloody war.”

Abraha was fortunate enough to receive asylum in Sudan, where he spent the next 3 years studying Arabic. In 2003, he got his first job as an interpreter working with the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees interpreting for Somali and Arab refugees. After working with them for three years, he applied, and was accepted, to immigrate to Canada as a government-sponsored refugee.

Once in Canada, he began to rebuild his life, starting by looking for work as a mechanical engineer. Abraha found the market in Toronto was saturated. Worried about finding work and providing for his family, he began talking to others in the community and asking for advice.

A women he knew found out about his experience in Sudan told him that he should get trained to interpret in Canada instead of looking for work as an engineer. She connected him to Multilingual Community Interpreters Services, a social enterprise that provides training for interpreters in order to remove language barriers for non-English speakers. Three months later he was certified as an interpreter in Tigrinya, one of three official languages in Eritrea, and Amharic, the official language of Ethiopia.

Within Ontario, local organizations often provide interpretation services and absorb the cost. In the GTA, the Healthcare Interpretation Network coordinates interpretation services within hospitals while health agencies in the community provide these services to individuals upon request. However, services are sparse for more rural communities. With health equity becoming a guiding principle of health care service delivery, it is increasingly important that accurate and unbiased interpretation services become available to those who need them both in urban centres and rural areas.

About 13,090 Ethiopians currently live in various parts of the GTA, with an estimated 70,000 people of Ethiopian descent. Unlike other immigrant groups, there isn’t an official ‘Little Ethiopia.’ Rather, there are pockets of immigrants that congregate around churches and restaurants. “The community is scattered,” says Abraha. “In the West there is an Eritrean Orthodox Church at Jane. So there are a couple of Eritrean families who are close to this church.” And in the east, between Greenwood Ave and Monarch Park Ave, an unofficial “Little Ethiopia” has formed on the Danforth.

The life of an interpreter changes quickly. Interpreters are hired as freelance workers by organizations like Access Alliance — a community health centre that provides access to primary health care and social services — on an as needed basis. That means that Abraha never knows where he’ll be called to next.

And at times it can be risky. He’s been sent to assist front line staff in psychiatric emergencies, and to interpret during infectious disease appointments. “You have to wear a mask over the mouth, and stay in the room with the patient for hours helping the nurses and the different doctors.” Being around infectious diseases is scary, but Abraha believes it’s his duty to be there for the patient. “For the sake of the person, you have a moral obligation to go and to help them.”

The role of an interpreter is often misunderstood — reduced to verbally translating words from language to language. But that’s only scratching the surface. Effective communication is about context. Interpreters, who are often immigrants themselves, are able to help bridge gaps between patients and providers by drawing on their lived experiences.

However, as Abraha explains, the cultural practices within the Ethiopian community often don’t align with what’s considered professional practice among interpreters. An interpreter must remain impartial and professional at all times. But clients are constantly inviting him over for food and coffee, or asking to drive him to his next appointment as a form of gratitude. “It’s difficult because if you go to the house of the family, they have to provide you with whatever they have. So to see them happy, I accept water. Other than that, I don’t.”

Navigating the cultural context extends beyond social etiquette. “Your job is to interpret, not to help them,” Abraha explains. Interpreters are duty-bound to verbally translate whatever the doctor or the client communicates, not to pick and chose what to transmit. “Sometimes the clients tells you something which they don’t want to inform the doctor, because they consider you like a brother.” Part of the job for Abraha is to clearly communicate the boundaries of the relationship, and to make sure that the client understands that difference between a paid, impartial interpreter and a new friend.

Abraha truly wants to help — it’s a drive that undergirds his career with Access Alliance and something that has made him successful in his field. He’s not only well known among health care providers, but he works with a broad spectrum of professional services, each of which exposes him to different kinds of emotionally and psychologically difficult situations.

Working at the Immigration and Refugee Board, for example, comes with its own specific challenges. The stakes are high. “When immigrants come here to Canada, they are asking to become either asylum seekers or refugee claimants. In that situation it is very challenging, because if he is rejected, he’s automatically sent back to his country. He’s going to be deported.”

As Abraha recounts interpreting for the Immigration and Refugee board, he becomes restless. “We become very anxious, very tense. It’s a situation where your role is very important,” he says. “They call these people the voiceless. You become their voice in that situation, and your role is very crucial. One mistake could mean destroying their life.”

Despite all of the freelance work, Abraha’s salary as an interpreter is still not enough to sustain him and his family. In addition to working full time during the week, he also works weekends as a concierge for a residential building in downtown Toronto. To find community, he is active in his church.

Regardless of its downsides, when Abraha talks about his work, he perks up and a wide grin spreads across his face. “I get a new experience every day.”

After 15 years as an interpreter, he doesn’t have any regrets about leaving the world of engineering. “I’m not working with a machine. I’m working with people, with my community. I want to pursue this profession the rest of my life.”

The job is difficult, the pay is low, but Abraha says he’s happy. “I’m very rich,” he says. “I can say I’m very rich in all aspects.”