“If Jesus were alive today, he would not be hiding in his church. He would be out with his people,” says Father Hernan Astudillo.

When the pandemic hit and places of worship were forced to close their doors, Astudillo took his message of hope and solidarity online and on the road.

Astudillo leads the congregation at San Lorenzo Church near Dufferin and Lawrence. The congregation of approximately 500 is made up almost exclusively of immigrants and refugees from across Latin America, many of whom had fled the conflicts of the 70s and 80s that spread across South and Central America.

The congregation at San Lorenzo is a tight-knit community that relies on each other and welcomes newcomers regularly. When the pandemic forced the parish’s doors to close, Astudillo’s phone began to ring. “Many in the community felt isolated, fear, and despair,” he says. Concerned about his congregation’s most vulnerable members, he decided to bring faith and community to them.

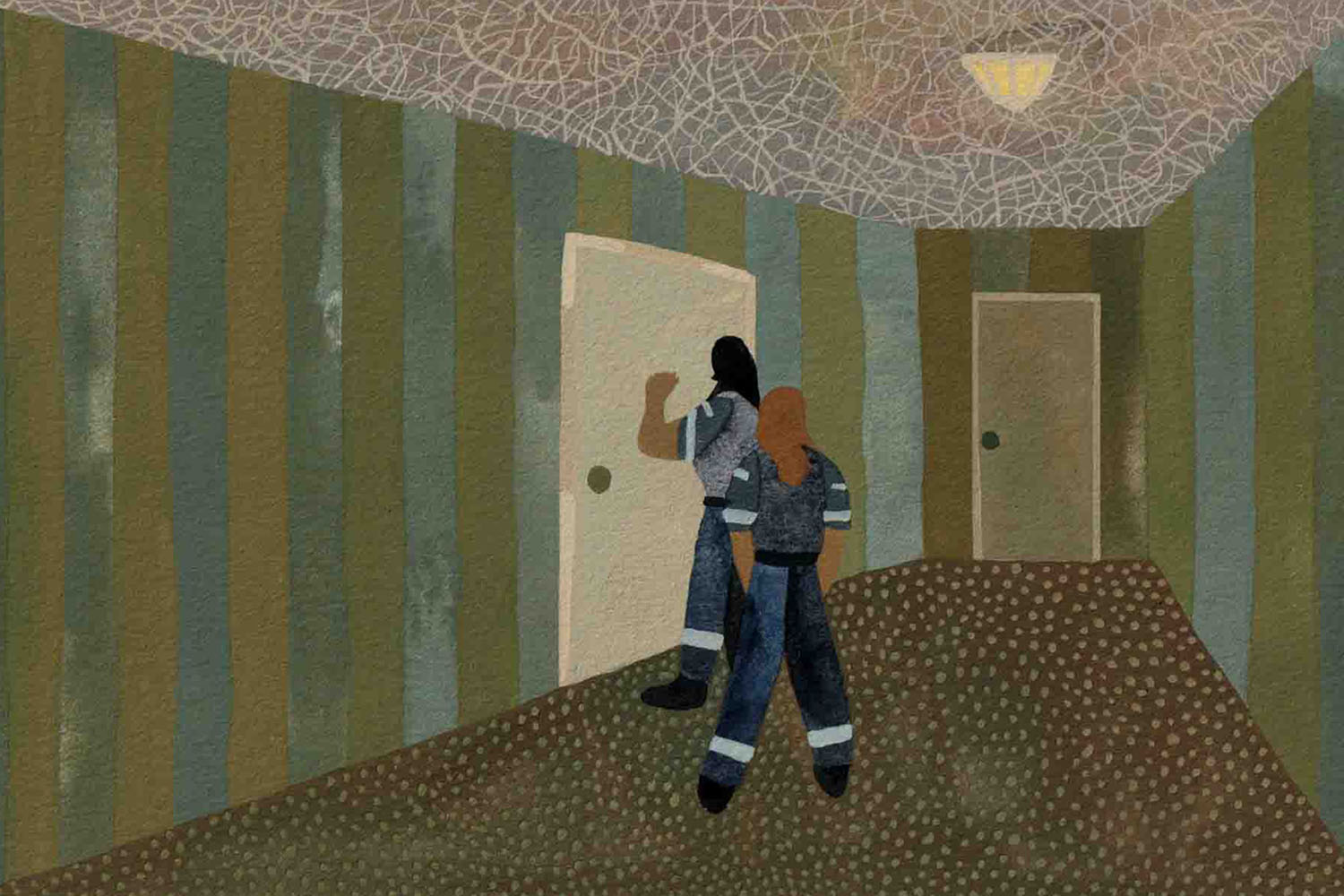

One bright morning in October, Astudillo visits Carmen Rosa at her Scarborough home and is greeted with a bottle of hand sanitizer and tragic news. Rosa’s niece back in El Salvador has just passed away from kidney disease overnight. Rosa underwent back surgery in March, around the same time that places of worship were forced to close due to COVID-19 measures. “After the surgery I was homebound, I could hardly stand. And then the pandemic,” says Rosa. “People are lonely and depressed. There is a lot of fear.”

In Rosa’s living room, they pray together.

“It’s not just about spirituality, it’s community,” says Rosa, speaking about Astudillo’s outside-the-box approach.

Astudillo is a refugee himself, having fled political instability and religious persecution in Ecuador. After arriving in Canada in 1992, Astudillo faced many of the same challenges members of his congregation faced as newcomers to Canada—language barriers, unemployment, and poverty. Astudillo survived by busking, playing his guitar and pan flutes in the subway and along Yonge Street while living in a small room in Kensington Market. By 1999, Astudillo had been ordained as the first Hispanic Anglican priest in Canada and had established the first Spanish-language congregation in Toronto.

Over the years, Astudillo has built a loyal following among Toronto’s Latin American diaspora, due in part to the brand of Christianity he practices. Astudillo is a proponent of Liberation Theology, a belief that the original message of Christianity was one of political activism, of social and economic justice and—as one of the founders of Liberation Theology, Gustavo Gutierrez put it—a “preferential option for the poor.”

The pandemic has been particularly harsh for the Rojas. The family of three, originally from Nicaragua, were the priest’s next stop. Rene and Lesbia both suffer from chronic health conditions, and Rene recently had a kidney transplant. Their son, Kenneth, is blind. All three are considered high risk and have been following strict distancing measures to avoid infection.

“I’m in and out of the hospital a lot recently,” says Lesbia. “It’s a terrible fear going there but what can one do?”

As much as they miss attending mass, the Rojas have not set foot in San Lorenzo since Toronto went into lockdown in the spring. “You never know where this virus is now and I can’t risk spreading it in the parish, or to Father Hernan,” Says Lesbia, “I miss being at the parish—my friends, the community, it’s very important for all of us. Father Hernan does so much for us and the other families.”

For the Rojas, Astudillo’s visits help break the sense of isolation that has set in over these last few months. Kenneth, who played the drums in the parish band before the shutdown, says he has struggled with loneliness and depression during the pandemic. Rene, who works at a car dealership, has had his hours cut to part-time as sales have slowed. He says he doesn’t leave his work station, which is surrounded by plexiglass. “I go from home to work, work to home. That’s it,” he says. “I don’t go out because I’m high risk, as is my wife. And Kenneth of course.”

Astudillo says the feelings of isolation and despair felt by many members of the congregation have been exacerbated by the crisis back home, as infection rates exploded in Latin America. As of November, according to John Hopkins University, four of the 10 hardest hit countries are in Latin America, with Peru sitting just outside the top 10 at the 11th spot. “We were not able to escape the virus,” says Astudillo. “Everybody at San Lorenzo has somebody affected back home, and from countries that do not have the resources we have here.”

Marco Suarez and Rosa Cuesta, long-time members of San Lorenzo, were also touched from afar by COVID. Rosa’s brother, Miguel Ayala, a doctor in Ecuador, his wife, and three of their children were all infected with COVID. Ayala remains in hospital in a medically induced coma, seven weeks after being diagnosed. “This virus is cruel, it doesn’t care who you are. If you’re a good person or not,” says Rosa Cuesta. “My brother is a doctor, he’s been helping fight the virus from the start.” The irony is that Ayala’s three eldest children are also doctors in the U.S., Cuba, and Spain. “They feel helpless, impotent,” says Rosa. “They followed in his footsteps and are unable to help or even be by his side.”

The family has taken to hosting nightly zoom calls with family spread across continents to pray for Ayala’s recovery.

While Astudillo sees the importance of visiting some of the most vulnerable in his congregation, he understands there are limits to how many people he can reach with that approach. Recently, he began streaming mass on social media platforms to reach as many of his followers as possible.

In September, when the pandemic seemed to be under control in Toronto and places of worship were allowed to reopen, he began holding short, 30-minute masses up to five times a day. With the coronavirus still roaming through the community, the congregation was cautious about heading back to church. This means Astudillo frequently performs mass for as few as a single parishioner at a time.

Astudillo admits that home visits and streaming platforms cannot replace the sense of community that exist at the parish, but he says he will continue to do what he can, while he can.

Astudillo, approaching 60, has health concerns of his own. He understands the potential hazards in his line of work, but says that he puts his trust in science and public health measures. “I understand the risk, but with precautions, I am fulfilling my responsibility,” he says. “I do it because they need comfort. Our people at San Lorenzo, many have a lot of pain and trauma in their histories.”