Cathy Parkes never intended to put her father, Paul Parkes, in a long-term-care home. The very notion of confinement ran contrary to Paul’s nature. He was a consummate outdoorsman—a fisherman and hunter who seemed to be on intimate terms with the troposphere. He could glance at the sky and spot the precise moment when the wispy cirrus clouds above him started to congeal, portending rain. During childhood, Cathy and her two brothers often went on camping trips with their father. “Once, in Killarney, we docked at an island with a mountain covered in blueberry bushes,” she recalls. “Dad said, ‘I’m not getting out of the canoe. A storm’s coming.’” The sun was beating down, and Paul’s prediction seemed outlandish. But he was right. “As soon as we reached the top of the mountain,” Cathy says, “a wicked storm broke out.” She and her brothers dashed to the base, where Paul was waiting in the canoe to ferry them back to the campsite.

When Cathy was a child, she couldn’t imagine that such a man would one-day find himself weakened, immobile, and confined to a tiny room. But in 2016, at age 82, Paul fell while gardening and was unable to get up. His wife found him an hour later keeled over by a flower bed in their Oshawa backyard. He was later diagnosed with hydrocephalus, a condition whereby fluid builds up beneath the skull, damaging the brain and causing mobility issues, memory loss, and urinary incontinence. Paul’s wife was experiencing cognitive decline and could offer only limited support. In 2018, Paul moved to Pickering, down the street from his daughter. For eighteen months, she was his primary caregiver. “Dad was losing his mobility,” Cathy says. “And I was hurting myself trying to lift him.” As his condition worsened, she forced herself to confront a painful fact: Paul needed more help than she could give.

Cathy knew that long-term-care facilities—or nursing homes, as they’re often called—have a bad reputation in Canada. In the 2000s, her grandmother had been abused and beaten in a nursing home. She also knew that there was nowhere else her dad could go. She contacted her Local Health Integration Network, the regional organization that administers placements, and was advised to submit a list of preferred facilities. Her first and second choices had near-decade-long wait lists, so she settled on a place Paul could get into: Orchard Villa, a 233-bed facility operated by Southbridge Care Homes, a for-profit company. The place was far from charming—she took an online tour and concluded that it resembled “a sad, run-down hospital”—but at least it was nearby. Also, Patricia Watson—Cathy’s mother and Paul’s ex-wife, with whom he was friendly—volunteered at the centre regularly and could look out for his well-being.

In early November, Paul moved into Orchard Villa, which was even more depressing than Cathy had expected. The floors were filthy, the windows were so grimy you could barely see through them, and, in parts of the building, the smell of excrement was so overwhelming it made her want to retch. To monitor patients, staff would leave them in the hallways within sight of the nurses. Whenever she passed a nursing station, Cathy saw crowds of ten or fifteen wheelchair-bound residents, some asleep, some calling for help, some staring listlessly at the walls. “I felt terrible leaving him there,” she says.

In time, though, she convinced herself that she and her father had reason to feel lucky. The staff at Orchard Villa were clearly overworked, but many seemed genuinely concerned about Paul’s well-being. Paul made instant friends with Milton, his eighty-year-old roommate, with whom he had lively debates about the Bible. Milton, a Methodist, preferred the more uplifting passages in the Gospels, whereas Paul, a Pentecostalist, adored the Book of Revelations, the apocalyptic final chapter of the New Testament, with its deadly thunder and annihilating hail storms. The duo would spend hours together watching Paul’s favourite channel, the Weather Network, each man lying in his separate bed and staring at his own TV.

They watched the news too, which in January became increasingly preoccupied with COVID-19. The crisis seemed far away, but like a hurricane that swells up on one side of the planet only to make landfall nearby mere days later, the virus travelled quickly. Orchard Villa saw its first case in early spring, and by the end of summer, 70 residents had died, a mortality rate of 30 percent. Cathy got her first indication that something was terribly wrong at the home on April 9, during a phone call with her father. “I need you to get me out of here,” he told her.

Of the 3,500 Ontarians who’ve died of COVID-19, 2,400 were long-term-care residents—a number that will continue to grow as the second wave takes its toll. Nursing homes have argued, in court filings and public statements, that the carnage can’t be avoided. The pandemic, they claim, is akin to an act of God—erratic and unstoppable. But while COVID-19 was indeed unexpected, the industry’s incompetent response was entirely foreseeable. The outbreak put pressure on a system that was already buckling, with predictably disastrous results. The storm had been building for decades. The warning signs had long been visible, if only we’d bothered to notice them.

The history of nursing homes in Ontario is a Dickensian tale, with all of the pain, squalor, and lurid suffering that term implies. It begins, according to historian Jim Struthers, in the late nineteenth century, when the province experienced an unprecedented demographic crisis thanks to public-health measures, like clean water and urban sanitation, which enabled Ontarians to live longer than ever before. Between 1871 and 1901, the percentage of citizens aged 60 or higher nearly doubled. (Today, Canada is in the midst of another unprecedented demographic crisis as the boomers enter old age. One of the ironies of unprecedented demographic crises is that they are, in fact, amply precedented.)

In the 189os, the country went into recession, leaving much of its burgeoning elderly population destitute. Having nowhere to go, many seniors moved into the nation’s poorhouses—dormitories, with more than a little resemblance to prisons and labour camps, on farmland far from the city centres. When entering these facilities, residents forfeited their right to vote, to live with their spouse, or to leave the property without the superintendent’s permission. Those who were able, were put to work in the fields; those who weren’t, were confined to attics or basements. As elderly people crowded into the poorhouses, these attics and basements became, by default, the country’s original seniors’ homes.

Struthers argues that today’s long-term-care facilities have had a difficult time escaping this grim history. “From the very beginning, it was fused in the public mind that old age and care homes were places of desperation, poverty, and misery,” he says. “There was a lasting, powerful stigma. These were the places you’d never want to enter on your own volition. They were the places where you went to die because nobody was going to look after you.”

In his historical writing, Struthers tells a depressingly recursive story: things get better, and then, sooner or later, they get bad again. At many points since the 1890s, bureaucrats and politicians have improved the conditions in seniors’ homes. But repeatedly, the industry has regressed to its Dickensian mean. The long-term-care facilities of today don’t perfectly resemble their poorhouse forebears, but they’re more similar than any of us should want them to be.

The first period of reform began with the expansion of the postwar welfare state. In 1949, Ontario passed the Homes for the Aged Act, which replaced nineteenth-century poorhouses with clean, sunny retirement homes modelled, in true postwar style, on the suburban family abode. These facilities enabled many elderly Ontarians, poor and affluent alike, to live with dignity. But they were exclusionary in another way: their operators refused to accept overly sick or immobile residents whose presence might undermine the country-club ambience. “Homes for the aged were not medical facilities,” says Struthers. “You were expected to be able to walk into them, rather than being wheeled in.” At the same time (thanks to further “unprecedented” growth in the elderly population) hospitals found themselves overwhelmed with patients suffering from respiratory, cardiovascular, and digestive ailments.

These patients—cruelly nicknamed “bed blockers”—posed a problem for the system. They were too sick for the homes for the aged but healthy enough to live for years, consuming limited hospital resources. To free up space, municipalities began quietly discharging them into a new class of unregulated private facilities, many run by slumlords. In one such home, residents—some with black eyes or bloody gashes on their legs—were confined to seven-person rooms in which the interior door knobs had been removed. In another, blind people were forced to eat the scraps off their fellow residents’ plates. The Homes for the Aged Act had greatly improved quality-of-life for one class of seniors—those healthy enough for the newly built retirement homes. At the same time, the system was consigning the frail and the sick to a different type of ad hoc facility—a waystation between the retirement home and the hospital every bit as terrible as its Victorian predecessor.

Such in-between facilities still exist today. We call them long-term-care centres. They are perhaps better than they used to be, but the difference is one of degrees, not one of kind. The resilience of long-term-care centres attests to a simple fact: as people live longer they develop medical needs that don’t warrant hospitalization but nevertheless require ongoing supervision and care, the kind a simple retirement home cannot offer. In the 60s, the province worked to formalize this new class of homes through regulation, inspections, and the establishment of a universal per-diem subsidy for residents. Many cities ran their own publicly funded facilities, which upheld higher standards than their for-profit competitors. And in the early 90s, members of Bob Rae’s NDP government discussed phasing out for-profit care altogether.

But in 1995, Rae lost an election to Mike Harris’s Progressive Conservatives, who opted instead to re-engage the private sector to address a growing shortage in long-term-care beds. Once again, a system that was gradually becoming more humane relapsed to something like its original state. Under Harris’s plan, long-term-care facilities would continue to receive government funding on a per-patient basis, but they’d be built and operated by for-profit companies, mainly the growing cohort of chains like Chartwell, Sienna, and Extendicare, which already had a foothold in the industry. Harris’s scheme reflected then-fashionable notions about the superiority of the private sector. In a competitive market, the theory goes, homes would one-up each other, pushing the industry toward better-quality care.

But the market was never really competitive. Since the 90s, the number of available beds has always been lower than the number of prospective residents. In such a system, people don’t choose freely between multiple options; they go wherever they can. And companies have few incentives to treat their residents well, since each facility gets the same government allocation regardless of client satisfaction. To make a profit, then, operators must run their nursing homes like discount motels. The trick is to somehow bring expenses below an already slim and inflexible budget.

And so, as research by the sociologist Pat Armstrong reveals, Ontario’s chain nursing homes became adept at cutting corners. This meant crowding patients four to a room, scrimping on cleaning services, contracting external caterers to bring in prepared meals rather than cooking onsite, doing laundry in massive industrial machines (the kind that destroy everything except synthetic fabrics), and allowing stockpiles of medical supplies, including personal protective equipment (PPE), to run perilously low. “There was only just enough of everything,” says Armstrong.

The biggest cost-saving measures were in the area of labour. Medical professionals (including nurses) are expensive, whereas low-skilled personal support workers (PSWs) can be hired for a mere $20 an hour. In Ontario nursing homes, PSWs comprise 58 percent of the workforce and perform almost all of the front-line care. The majority of them work part time, often without job security or benefits. During busy shifts, a single PSW might find herself taking care of 40 residents at once, and the work often resembles an assembly line, with a set number of tasks to be completed in a limited timeframe.

Of course, PSWs aren’t applying hubcaps to wheels; they’re taking care of fellow humans, a job that requires sensitivity, flexibility, and patience. “Long-term care is labour intensive,” says Gail Donner, former dean of the Lawrence S. Bloomberg Faculty of Nursing at the University of Toronto. “It takes time to help an elderly person shower or walk. It takes time to feed an individual with dementia who also has difficulty swallowing.”

Fast-paced care, then, is by definition poor care. It can lead to malnutrition, because residents are being hastily fed; infections, because they are being improperly cleaned or left for hours in unchanged diapers; or even death, because treatable ailments, from bed sores to diabetic wounds, aren’t being diligently monitored. For PSWs, the pressure to work speedily is a source of acute moral distress. In her research, Armstrong often surveys PSWs in Ontario homes. “We ask them about what it’s like when they leave work,” she says. “Quite a few say, ‘I go home and cry, because I wasn’t able to provide the care I knew my residents needed.’” When COVID-19 hit, it would fall to this harried, exhausted workforce to somehow contain the virus. No reasonable person could’ve expected them to succeed.

When the army arrived, the place was in disarray. The hallways reeked of rotting food. Residents in soiled diapers slept on bare mattresses amid flies and cockroaches.

The day Fred Cramer brought his mother, Ruth, who suffered from Alzheimer’s and dementia, to live in Orchard Villa, he left feeling uneasy. That afternoon, Ruth rang the call bell to request assistance getting to the washroom; 45 minutes later, a PSW finally arrived to take her there, only to leave her, unattended, on the toilet. When, four months later, Ruth suffered a dramatic fall, fracturing her nose, Cramer wondered if the apparent neglect he’d seen that first day had somehow contributed to the accident.

Cramer’s story was hardly anomalous. After Carolin Wells left her father, James Fleming, at Orchard Villa, she got used to receiving out-of-the-blue calls from the local emergency department. During his time at the home, James, who suffered from global aphasia, was repeatedly hospitalized for what seemed like preventable ailments: he suffered a nasty fall in the shower, he developed a case of pneumonia that turned into sepsis, and in an incident that still puzzles Wells, he sustained internal injuries to his rectum, which were so severe he needed stitches. (The home said he’d accidentally impaled himself on a piece of metal protruding from his wheelchair.)

When Simon Nisbet’s mother, Doreen, lost her mobility in a bad fall, he too took her to live at Orchard Villa and found himself constantly advocating for her needs. To avoid wearing himself out, he decided to overlook relatively small problems—like when Doreen’s food came half-frozen—and concentrate on bigger issues, like when the staff issued her a leaky bed pan and told him, after he requested a replacement, that they didn’t have back-up supplies. “In the beginning, I was gung-ho to fight every fight,” says Nisbet. “But you get to a point where you think, ‘As long as the big things are looked after, I can let the little things slide.’”

Like Cramer, Wells, and Nisbet, Cathy Parkes found herself visiting Orchard Villa often and advocating tirelessly on behalf of her father. On occasion, Paul would be left for hours in soiled diapers, or he’d miss breakfast and lunch, because the staff had neglected to put him in his wheelchair, and he had no way of getting to the dining hall. A few days before Christmas, Cathy got a call from a nurse saying that Paul had been catheterized because he hadn’t urinated in days. She rushed to Orchard Villa, where she found her father in a state of delirium and agitation. She checked his catheter bag. “The liquid in it looked like black coffee,” she says. At her request, Paul was admitted to hospital, where he was diagnosed with a urinary tract infection so severe it had morphed into kidney failure.

Perhaps the scariest incident was in late January, when Paul called Cathy in a state of acute panic to say that his roommate, Milton, was choking. “We’ve pressed the call button, and nobody’s coming,” he told her. “I said, ‘Dad, hang up the phone,” Cathy recalls. “I called the nursing station, and told them, ‘You have to get down to room B24.’” The staff did as she said, but Cathy wonders what might’ve happened to Milton if she hadn’t intervened. (I asked the management at Orchard Villa to respond to the various allegations involving Milton, Paul Parkes, Ruth Cramer, James Fleming, and Doreen Nisbet. In an email statement, Candace Chartier, chief seniors’ advocate and strategic partnerships officer for Southbridge Care Homes, explained that she would not address individual accusations of mistreatment or neglect. “Out of respect for the privacy of our residents and their families,” she wrote, “and in keeping with our obligations under health data privacy legislation, I cannot discuss any specifics regarding individual residents.”)

Of course, Cathy contemplated pulling her father from the home, but such a move would’ve been destabilizing; in addition to his friendship with Milton, Paul had developed a romance with Janet, a woman in her 60s with high cheekbones and silver hair. And besides, there was nowhere else for him to go. “I saw that everything was wrong,” says Cathy. “But I had no choice but to put faith in the people taking care of him.”

To blame Cathy—or Cramer, Wells, and Nisbet—for failing to spot the warning signs is to completely misunderstand their stories. They were clearly dissatisfied with the quality of care at Orchard Villa, and they intervened repeatedly to make things better. If anybody is guilty of ignoring warning signs, it’s not them—it’s us. Over the past two decades, there’s been no shortage of evidence about the dangers of long-term care in Canada, where the proportion of people who’ve been exposed to hepatitis C is three times the national average, and an influenza outbreak at a single facility can infect 50 percent of the population.

It isn’t just illness residents must fear. In 2016, Elizabeth Wettlaufer, a long-term-care nurse in various southern-Ontario homes, confessed to murdering eight residents and attempting to murder six more. In 2018, a CBC Marketplace investigation found that an average of six long-term-care residents in the province are abused by staff each day, and in 2019, a study from the Ontario Ministry of Health reported that, over a seventeen-month period, provincial nursing homes had seen 600 food-related “incidents,” with residents missing meals, choking while being fed, or developing gastrointestinal conditions from contaminated products. These stories—and many others—suggest a culture of impunity and dangerously low oversight. None of this was a secret. For the last thirty years, journalists, academics, and health inspectors have been sounding the alarm about long-term care. Like an unanswered call bell, it kept on ringing.

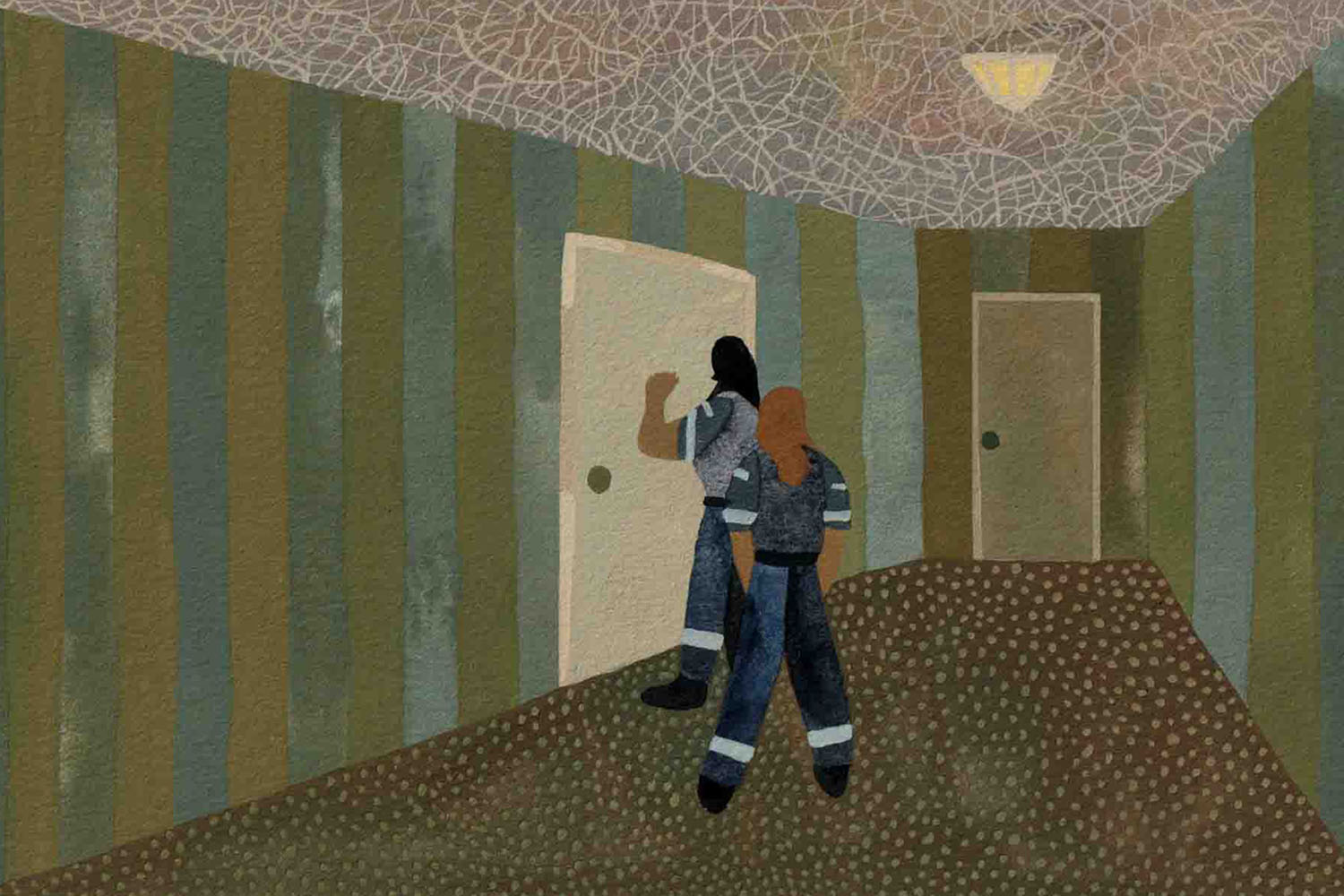

When Paul asked Cathy to get him out of Orchard Villa, she didn’t know what to think. It was the Thursday before the Easter long weekend, and she hadn’t seen her father since lockdown began four weeks earlier. Because of his condition, Paul spoke haltingly and often lost his train of thought. Was he being serious, or flippant? When Cathy pushed him to explain himself, he became confused. “Eventually,” she recalls, “He said, ‘Forget about it.’”

The next day, she checked a website for the Durham Region that tracks disease outbreaks in nursing homes and found the source of her father’s distress: COVID-19 had come to Orchard Villa. Cathy immediately called a nurse at the home, who, she recalls, told her that four staff members and four residents had tested positive, and two of the residents had died. “Is the virus in my dad’s ward?” Cathy asked. “Yes it is,” the nurse replied.

She spent the long weekend in a state of panicked confusion. On April 11, her birthday, she called her father and found him uncharacteristically quiet. “He barely spoke at all,” she says. “He managed to say ‘yes’ and ‘I love you.’” She called a nurse whom she trusted, and he confirmed that Paul had a low-grade fever but hadn’t been tested for COVID-19. (The home had reserved a limited number of test kits for severely sick patients.) She then asked the nurse how he was doing. “I’m exhausted,” she remembers him saying. “Nobody’s coming into work. We’re down to 50 percent of our normal staff, and I haven’t left in days.”

The next day, Easter Sunday, she called the home repeatedly, but nobody picked up. On Monday, she got through to another nurse, who told her that Paul’s temperature was 37.7 Celsius, the same, down to the decimal point, as it had been two days earlier. Could the number really have remained stable? “I suspected that he was reading me old information,” says Cathy. She demanded that her father get tested, and the nurse promised to grant her request. Then she asked about his own wellbeing, and she recalls that the nurse echoed his colleague’s words: “It’s crazy here. We don’t have enough PPE, and we don’t have enough staff.”

Cathy decided to sound the alarm. She emailed the premier’s office, the provincial ministry of health, and the mayor of Pickering. “Please help,” she wrote. “Orchard Villa needs support staff and PPE, and they need these things immediately.” The office of the deputy mayor, Kevin Ashe, returned her message, and reassured her that the home was suitably staffed and supplied with PPE. Cathy later spoke with the director-of-care at Orchard Villa, who corroborated the deputy mayor’s statements. “It was so weird that the staff was saying one thing,” says Cathy, “while the management and the mayor’s officer was saying another.”

On Tuesday, she insisted on seeing her father. A PSW told her that, if she went to the parking lot, she could glimpse Paul from his second-floor window. From outside the home, Cathy called her father’s line. The PSW held the phone to Paul’s ear and angled his mechanical bed toward the glass. “He was comatose on his back,” says Cathy. “He couldn’t speak. I kept asking him to turn his head toward me, but he couldn’t even do that.” She didn’t yet know the results of Paul’s COVID-19 test, but she saw that he was terribly unwell. “I thought, ‘This is my worst fear,’” she says.

Immediately, Cathy called Ajax Pickering Hospital and arranged for Paul to be brought in. A senior staff member at Orchard Villa discouraged this action. “She told me that the hospital would turn Paul back,” says Cathy. “She asked me if that’s what I wanted for my dad?” In the end, though, it didn’t matter. On the day Paul was to be brought to hospital, Cathy got a call from Orchard Villa. “Paul Parkes has died,” the caller said. “When are you coming to collect the body?” She burst into tears and confessed that she didn’t know what to do next. “You don’t have plans for the body?” the caller asked. “No,” Cathy responded. “I didn’t expect my father to die today.” She’d still hoped that, this summer, as in years past, she and Paul would head to Lake Ontario to eat ice-cream and watch the sailboats. She knew he was nearing his final years but hadn’t imagined the end would be so swift.

In truth, she hadn’t known what to think. During the lead-up to her father’s demise, she’d heard conflicting stories about the situation at Orchard Villa. One, coming to her via official channels, suggested that the home was handling the crisis as well as could be expected; the other, conveyed through informal conversations with nurses, indicated a complete breakdown in normal operations. On April 22, the Ontario Government announced that it was calling in the Canadian Armed Forces to assist at Orchard Villa and four other nursing homes.

Less than a month later, the CAF filed its report, suggesting, to Cathy, that the latter story had been true. When the army arrived, the place was in disarray. The hallways reeked of rotting food. Residents in soiled diapers slept on bare mattresses amid flies and cockroaches. In a desperate attempt to prevent people from wandering the corridors, staff members had made walkers inaccessible and placed bedding on the floors, since seniors with mobility issues often struggle to get up from low beds.

Conditions weren’t merely degrading, though; they were also dangerous. In their haste, staff administered medication incorrectly. They ignored safety protocols around eating and hydration: sometimes they left meals on side tables that residents couldn’t reach or failed to properly sit residents up before feeding them. One woman choked to death during a meal. Another fell and likely fractured her hip, an injury that went unnoticed until a senior nurse intervened. All supplies, from linens to soaker pads to wound-care materials, had run dangerously low. Staff at every level, including doctors, had failed to properly use PPE.

In her email, Chartier, of Southbridge Care Homes, addressed the broad allegations in this article and the military report. “We take all concerns regarding our homes seriously, including those expressed by the families and the CAF report,” she wrote. “Our residents are at the heart of everything we do, and we remain committed to ensuring that all of the concerns are appropriately addressed and that our residents receive a high standard of care at Orchard Villa.” Chartier also pointed out that Orchard Villa was hardly the only Ontario nursing home to face staffing shortages during the early days of the outbreak.

Like a front-line hospital from some lurid nineteenth-century battlefield, Orchard Villa became a place of death. James Fleming, the man who’d been admitted multiple times to the emergency ward, was among the first residents to succumb to the virus. His daughter found out when she called to get an update on his health. (The update was, “I’m sorry. He’s gone.”) Ruth Cramer, the resident who’d fractured her nose in a fall, died in April, four days after testing positive for COVID-19. When her son came by Orchard Villa to pick up her things, he witnessed the morbid spectacle of orderlies loading bodies into a van.

After Simon Nisbet’s mother, Doreen, was diagnosed with COVID-19, he took her out of the home and had her admitted to hospital. By this point, Nisbet says, she was malnourished, dehydrated, delirious, suffering from kidney failure, severely constipated, and gasping for breath. She survived, but Nisbet suspects that it was a close call. Janet, the woman Paul had befriended, died four days after he did. Cathy can’t shake the feeling that she contracted the virus from him. And Milton, Paul’s roommate, was present when the body was wheeled out of the room. “I heard from Milton’s family that he was absolutely distraught,” Cathy recalled. She suspects that, at this point, he too had contracted the virus. He died 48 hours later.

For the last thirty years, journalists, academics, and health inspectors have been sounding the alarm about long-term care. Like an unanswered call bell, it kept on ringing.

The disaster at Orchard Villa and numerous other nursing homes isn’t an act of God or an unforeseeable tragedy. It’s a moral indictment, and not only of the nursing-home industry but of all of us. It has revealed a culture of astonishing stinginess. We’ve embraced a lean, low-cost model for long-term care not because it works but rather because it’s cheap. Ultimately, we got what we paid for.

A second wave of the virus is now underway. As outbreaks continue at Rockcliffe Care Community, Main Street Terrace, and more than 90 other Ontario facilities, the events at Orchard Villa offer a grim portent for how events may play out. By some measures, the industry is better prepared this time around: tests are more widely available, masks and PPE have gone mainstream, and many Ontario homes have partnered with local hospitals to get help with infection prevention and control. But homes are still dangerously understaffed, and most have insufficient back-up staff for when the virus hits, and workers, due to illness or fear, inevitably stop coming in. (According to Chartier, of Southbridge Care Homes, the company is better prepared for the second wave. It has beefed up its staffing, instituted regular mandatory testing for employees, invested in infection prevention and control, and partnered with Lakeridge Health, a local hospital, which is assisting with staff management and oversight. Southbridge Care Homes is also the defendant in several lawsuits, including one class action, related to the deaths and alleged negligence that occurred at Orchard Villa during the COVID-19 pandemic. The cases are ongoing.)

Even if the second wave turns out to be less deadly than the first, the situation in long-term care remains untenable—and needs to be overhauled. The events of the past year have taught us a great deal about who counts in this country and who doesn’t. For Armstrong, it demonstrates a bias against the elderly—those who are no longer economically productive, energetic, or conventionally beautiful—and against certain types of labour, which have historically been performed by women. “We’ve been undervaluing caregiving forever,” she says. “We assume this is something any woman can do by virtue of being a woman. We haven’t treated it as skilled work that needs to be recognized and fairly compensated.”

If meaningful reform is to happen, it must begin with labour. The industry must become less dependent on the unskilled, the low-paid, and the precariously employed. Because many PSWs lack stable, full-time employment, they often work at several facilities. Last spring, PSWs were key vectors for COVID‑19: when they travelled from job to job, they brought the virus with them. A well-paid, properly trained workforce—one whose members had basic knowledge of virology and weren’t shunting between multiple workplaces—might’ve been better able to contain the spread.

In its latest budget, the Government of Ontario has pledged to hire tens of thousands of long-term-care workers by 2025. But what matters is not only the number of workers but also the kind of work they do—and the expertise they possess. To that end, better training is needed. Canadian universities should give undergraduate nursing students the chance to specialize in gerontology, something that, bizarrely, almost none of them do. Nursing homes should also be forced to stop relying so heavily on PSWs. Instead, they must be required to have a large in-house cadre of registered nurses (RNs), nurse practitioners (NPs), and physio and occupational therapists—as well as at least one specialist in infection prevention and control. “In European nursing homes, RNs and NPs make up 65 to 70 percent of the staff,” says Veronique Boscart, a gerontological nurse and researcher in long-term care. “In Canada, they make up 10 percent.”

An investment in staffing and labour would be a gamechanger, particularly relative to the dismal status quo, but it still wouldn’t bring us anywhere near the standards upheld by European nations, like Denmark, which has made substantive investments in home care (everybody over 75 receives mandatory visits from a health worker) or Norway, where the number of for-profit homes is small and getting smaller. To bring our nursing homes into the twenty-first century, we must overhaul the architecture, replacing dingy, sunless facilities with airy, well-ventilated abodes. We must start collecting high-quality, longitudinal data on everything from staff job satisfaction to the number of times each patient is transferred to hospital. And we must embrace alternative models of care.

We might invest, for instance, in community nurses, who make daily rounds of houses where seniors live, providing the kind of basic upkeep that can prevent people, if only temporarily, from entering institutional settings. Or we might build facilities where the young and old cohabitate. “I lived in intergenerational housing during my student years in Belgium,” says Boscart. “It was expected that, for part of my rent, I would do groceries and keep an eye on my elderly neighbours.” Such a model may sound novel to Canadian ears, but elsewhere it’s unremarkable. It wouldn’t replace long-term care, but, if combined with other investments, it could take pressure off the system.

What’s called for, in short, is a complete break with history. Institutions that evolved from the poorhouses of the nineteenth-century must, belatedly, become medical facilities befitting the twenty-first. The obvious objection to such reform is that it’s expensive, to which the only coherent response is: Yes, it is. Human dignity doesn’t come cheap. Donner argues that, to fix our nursing homes, we need to rethink our health-care priorities. “A small amount of the public purse is spent on long-term care and home care,” she says. “A lot of money is spent on acute care. People want to have an emergency department within blocks of their house. They want to know that if they need some life-saving treatment, they’ll get it quickly. And so, long-term care always gets short shrift. Changing that is going to require trade-offs. Perhaps people will have to wait longer for elective surgery. I don’t know where the costs to society will be, but there are always costs.”

It’s high time we accepted those costs, although there’s no guarantee that we will: inertia and stinginess are powerful social forces. When asked if she sees COVID-19 as a turning point for the industry, Donner expresses ambivalence. “On my good days, I think, ‘It’s about time we got a wake-up call, and COVID gave it to us,’” she says. “At other times, I think, ‘There’s going to be a lot of fuss and bother, and then we’ll go back to business as usual.’” Boscart feels similarly conflicted. “Overall, I’m hopeful for Canada,” she says. “But I’m smart enough to have a retirement plan in Europe.”

Paul’s funeral, on April 18, wasn’t as cathartic as Cathy had hoped it would be. Because of the lockdown, only ten people were permitted inside. “We couldn’t hug each other,” she says. “We couldn’t even stand side-by-side.” After the guests cleared out, Cathy took a moment alone with her father. “He was emaciated,” she recalls. “His suit, which had fit him six months earlier, was three sizes too small.”

It wasn’t until the burial four days later that Cathy got the closure she’d wanted. Guests couldn’t stand close to one another, but at least they could gather outside, unburdened by the anxiety that indoor spaces now induce. Each of Paul’s children spoke, and together they sang his favourite hymns, “Blessed Assurance,” “Great Is My Faithfulness,” and “How Great Thou Art,” which envisions a divine presence in wild nature and the cosmos: “I see the stars, I hear the rolling thunder / Thy power throughout the universe displayed.” It was sunny outside, but with turbulent wind. “The weather was bizarre,” Cathy says. “Dad would’ve loved it.”