For the first two months of the pandemic Mike Pereira, his wife and two sons, parents, and grandparents, aged 98 and 88, all hunkered down together in a bungalow near Lansdowne and Davenport.

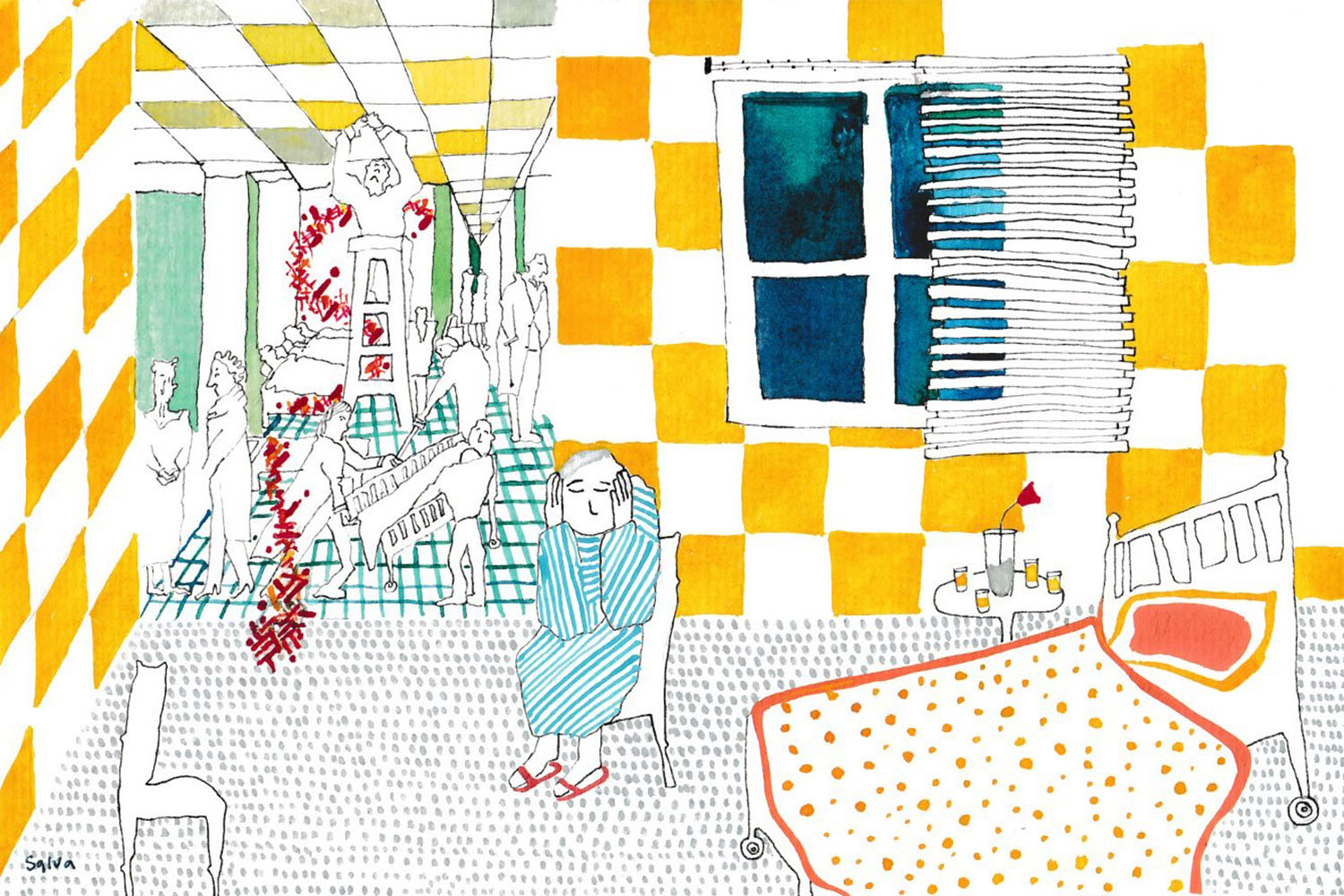

His grandmother’s Portuguese soap operas, variety shows, and news programs were a constant soundtrack in the house, layered overtop his mother’s non-stop vacuuming and the sound of the boys, ages 7 and 12, screaming into headsets as they played Fortnite with their friends.

Pereira and his family have their own house in Ajax, but like many families, early into the pandemic they decided to temporarily move in with his parents to help with grocery shopping and other errands.

“We were all crammed into this house when you couldn’t really go anywhere,” says Pereira, over the phone. “Everything was amplified in the early stages.”

But when the commotion became too overwhelming, the family would escape to the backyard or go for walks in the neighbourhood, where the usually bustling streets were eerily calm.

When lockdown orders were at their peak in March and April, cities experienced a newfound quiet. The roaring sounds of rush hour traffic, airplanes flying overhead, and drunken patrons spilling out onto sidewalks at 2:00 a.m. all disappeared. People reported hearing birdsongs for the first time and observed wild animals roaming city streets.

But as urban environments descended into stillness, inside individual homes a new cacophony of sounds emerged: overlapping Zoom calls, siblings fighting during the hours they should be in school or daycare, construction sites operating at all hours, and squabbling roommates stuck in quarantine together.

Noise has always been distributed unequally across the city, but the pandemic has exacerbated those inequalities, emphasizing the disparity between those who can flee to cottages in the Muskokas and the families crammed inside tiny apartments.

“Finding five to 10 minutes of quiet time is absolutely amazing,” says Javiera Quintana, a video producer who lives in an east end house with her husband, two kids, aged five and two, and her mom, 72. As she chats over the phone, children screech in the background.

“My toddler’s obsessed with a couple of toys that just play the same thing over and over. He’s in love with this Moana doll and as soon as the song finishes, he’ll push the button again” says Quintana. “The sound of Moana is better than the sound of my kid crying.”

But the noises coming from outside the house are more aggravating. On one side, it’s an orchestra of drilling, sawing, and hammering as the neighbours gut and rebuild their house. On the other side, loud drunken parties in the backyard are the norm. “Even when we weren’t supposed to get together with people, they were having pool parties at least two to three times a week,” says Quintana. “They’d be playing beer pong and it’s just like, guys, it’s a pandemic, this is how you’re going to get sick.”

These noises didn’t suddenly arrive during the pandemic—the construction began in February and rowdy pool parties happened last summer too—but Quintana says being at home all the time magnifies their impact.

“At the end of the day, we all end up exhausted,” says Quintana. “But is that because of the noise? Or because we’re all at home trying to hold it together, while we’re also worried about if we’re going to have a job in six months?”

Noise has always been distributed unequally across the city, but the pandemic has exacerbated those inequalities, emphasizing the disparity between those who can flee to cottages in the Muskokas and the families crammed inside tiny apartments. Quietness, and your ability to access it, has become a precious commodity. Yet it’s long been an invisible privilege of the wealthy.

According to a 2017 Toronto Public Health report on the health impacts of noise, around 50 per cent of residents in lower income areas are exposed to night noise levels over 55 dBA (A-weighted decibels). The World Health Organization’s health-protective guidelines for city noise pollution states that annual average night exposure should not exceed 40 dBA. “In Toronto, lower income populations who already experience poorer health are also more likely exposed to more noise than people with higher income,” reads the report.

Meanwhile in April, the province passed new regulation allowing construction sites related to the health care sector to operate around the clock and extending the hours of all other sites. Instead of allowing work from 7:00 a.m. to 7:00 p.m. Monday to Friday, with a 9:00 a.m. start on Saturday and no construction at all on Sunday, construction sites are now noisy from 6:00 a.m. to 10:00 p.m., seven days a week. The province said the longer hours were introduced in order to accelerate critical health infrastructure and to allow for more physical distancing between workers. But for some Torontonians who live near these sites, the noise has been unbearable.

“We are surrounded by a wall of noise on most days,” says Madison, who lives with her partner, in a one-bedroom apartment near Ryerson University. “We live right across from a huge tower being built. There’s a lot of beeping and banging going on starting around 7:00 a.m.,” she says. Coupled with that, many of the vacant units are being renovated, adding more construction noise that can happen at any moment.

Although the noise has given them headaches and makes it harder for them to focus while they work from home, Madison says some days they’re able to tune it out.

Andrea, who lives alone in a one-bedroom downtown condo, is unable to block out the incessant deafening sounds of her building’s clanging elevator.

“It literally sounds like banging pots and pans together, no exaggeration,” she says. “It happens every 20 to 30 seconds all day until about 1:00 a.m. The noise goes off every time the brake is engaged, so imagine every time someone goes into an elevator in a busy condo.”

She first noticed the noise in January, but it didn’t bother her too much since it only occurred every once in awhile and she was hardly home. In addition to her 9-5 office job, she worked part-time as a fitness instructor and a bartender.

“When the pandemic hit, I lost my two part-time jobs but thankfully was lucky enough to keep my full-time job and work from home,” says Andrea. “However, this meant that I was now stuck at home with a noise that I could not escape.”

The noise causes earaches, headaches, and lack of sleep. It gets so bad that sometimes Andrea debates sleeping on her balcony, which overlooks the Gardiner, reasoning that the whizzing of cars is more welcoming than the elevator. It’s been a physically and emotionally taxing six months, made worse because management hasn’t proposed any solutions to address the problem.

“I look forward to whenever I can go outside because my house is no longer relaxing for me. It’s become a source of stress.”

Hugh Davies, a professor at the University of British Columbia’s School of Population and Public Health who studies noise pollution, says that chronic noise exposure can have severe impacts on your health.

“Chronic noise exposure has been associated with heart disease, diabetes and other metabolic disorders, strokes, and adverse birth outcomes,” says Davies. “Noise isn’t causing these things through some unique pathway. Noise is causing the stress, which is causing these long-term diseases.”

Along with the decibel level, Davies notes that the actual content of noise impacts how much stress it causes. For example, people who dislike wind turbines are able to pick out the particular whooshing noise they make at very low levels because it triggers their annoyance. It’s why, during a pandemic when physical distancing is recommended, the sound of a pool party can be infuriating.

Although in the early months of the pandemic, the sound of kids playing in parks, cars honking, and booming summer street festivals temporarily went mute, the city’s soundtrack is beginning to return.

Pereira and his family are back in Ajax now, where the boys don’t have to share a room and Portuguese variety shows aren’t humming in the background. It’s a lot quieter than his parents’ place, but Pereira learned to adapt before they moved out anyway.

“I wrote an entire screenplay in those first couple months,” says Pereira. “I used to need quiet. Now I’m able to write with kids screaming in the background.”