Ryan Tong didn’t know exactly what he was looking for when he dove into Toronto’s commercial rental market in 2015. He just knew the landlord had to be OK with noise.

Onstage, Tong unleashes a fury of concentrated energy when fronting his hardcore band S.H.I.T., but offstage he is calm and even-keeled—the ideal candidate to navigate the complexities of operating a not-for-profit arts space in Toronto. Starting a DIY music venue makes no sense economically, of course, but Tong wasn’t motivated by money. Following the closure of SHIBIGBs, the punk venue on Geary Avenue where Tong had cut his teeth as an organizer, he wanted to create a space for his community in a city where low-cost, low-stakes venues had been rapidly closing.

After looking at many spaces that didn’t want to deal with the noise, he lucked out, finding a lenient landlord with a basement unit down a flight of stairs in a plain brick building on College Street just east of Dovercourt.

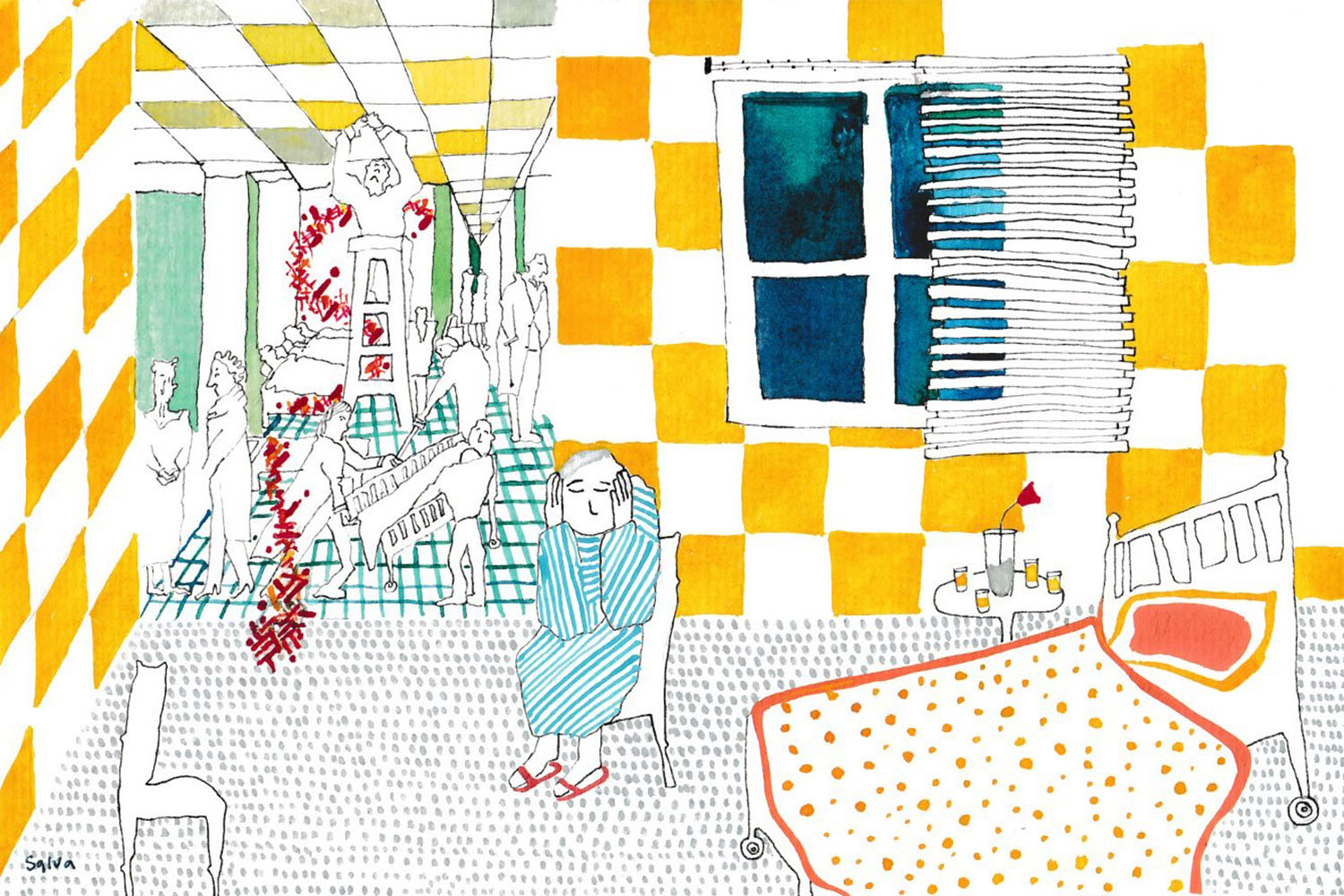

The space he created there, FAITH/VOID, became an ad-hoc community centre for Toronto’s sprawling and overlapping punk, hardcore, and electronica scenes. Like most DIY spaces, FAITH/VOID operated in a grey zone and without a license—something between an official venue and your friend’s living room. The bands played on the same level as the audience, everyone stomping on the same orange terracotta floors, reaching up to touch the low-paneled ceilings, fans dancing face-to-face with musicians screaming their lungs out.

Crunchy guitars, smashing cymbals, and deep electronic basslines weren’t the only elements that defined FAITH/VOID. The space was a gathering place complete with a record shop, exhibition space, comfy leather couches, and new finds constantly spinning on the record player. There was always someone to talk to, always something to be part of.

“I would often go to shows alone, but knew that I would meet new people,” says Elizabeth MacLeod, the guitarist and vocalist of Feels Fine who found a community there just after moving to Toronto from Scotland. “The best part about FAITH/VOID was that it was always open, always there. You could hang out for literally ten hours and run into your friends.”

A city’s DIY venues are community cultural spaces that perform a wide spectrum of services. They host concerts and exhibits. They’re often the places that incubate a scene or bands before they’re embraced by larger audiences. Established wherever there’s room, in former industrial buildings, storefronts, and mall basements, they’re spaces that are often created by marginalized communities to feel safe and supported. Most DIY venues define themselves in opposition to the economic paradigm that governs so much of Toronto, valuing community connections and deep aesthetic appreciation over profit.

“I was trying to cultivate a community and provide space for people to express themselves and connect with one another,” Tong explains. “Almost every day was an expression of that. It was the closest thing to feeling freedom.”

For almost four years, Tong ran his noisy utopia. Then, in February 2019, a weekend that happened to have back-to-back shows, new tenants moved into an apartment next door. That’s when Tong got hit with a noise complaint.

Reading through Toronto’s noise bylaws is like reading the city’s diary. The codes that govern Toronto’s daily operations reveal its deepest, truest values. Continued restrictions on Sunday noise, for example, are reminders of colonial Toronto’s Protestant roots. It also becomes apparent how much economic and symbolic value the City of Toronto places in noise, and in preventing it. Toronto may accept some noise as necessary and productive, but it rejects other noise as unnecessary and obtrusive.

Before last fall, the city’s noise bylaw worked under a vague principal of “general prohibition.” Anyone who was disturbed by any noise could get noise bylaw officers to enforce fines.

“The prohibition made no sense,” says Tong. “It allowed people to complain about children playing and babies crying.”

The new noise bylaw, adopted by City Council in October 2019, after five years of consultation, has specific decibel limits for amplified noise. Now, when a noise complaint is logged, the city sends bylaw officers—outfitted with pseudo-police uniforms complete with badges, epaulets, and sweater vests—to measure the noise levels with a decibel reader.

“Know your limit, play within it,” is how Rod Jones, the director of bylaw enforcement for the City of Toronto describes it. “Now a venue operator can track decibel levels and make sure they stay in the safe zone.”

But the bylaw works significantly differently when it comes to the most frequent culprit for noise complaints—construction. There, noise is restricted by time rather than decibel levels. No matter how loud construction on a tower may be, it gets a pass as long as it’s between 7:00 a.m. and 7:00 p.m. on weekdays, with a 9:00 a.m. start on Saturdays.

It’s also common for developers to apply for noise exemptions, receiving permission to work outside of designated hours. “Sometimes it makes sense to pull the Band-Aid off quicker,” explains Jones. “If they work longer, and work weekends, they can shave six months off a build.” That may expedite the process for a single building, but at the height of Toronto’s building boom the city has been subject to almost 20 years of jack hammering, metal clanging, pressure drilling, and engine rumbling. With more construction cranes than any city in North America, one construction project might end in Toronto, but three will begin.

While construction projects are consistently granted noise exemptions, DIY venues are consistently subject to noise complaints. Of course, organizers can apply for exemptions, but the process of obtaining permits is often inaccessible to spaces operating on a shoestring budget with no interest in getting tangled up with regulators who may shut them down.

“DIY spaces need to exist on their own terms,” says Tong. “I understand that in a city that’s an incredibly difficult thing to do.”

“FAITH/VOID was based on music that nobody had ever heard of,” says Tong. “It was the worst business model ever. That made it incredibly difficult to sustain financially.” While record sales, concert tickets, and the bar contributed toward monthly bills, Tong had to worry about the three-headed spectre of rising rent, property tax increases, and the looming possibility of the building being sold outright.

It’s the precarity of DIY spaces that makes them particularly vulnerable to noise bylaws. One noise complaint can set off a chain of events that can lead to a venue’s closure, as operators often don’t have the time or resources to sort through the bureaucratic process while running their space.

Mike Tanner, the development officer for the City of Toronto’s Music Office, understands the predicament that Tong and other DIY spaces find themselves in.

“When you’re a small operator, you’re subject to very large macroeconomic forces you have no control over,” says Tanner, who was hired by the city in part to protect spaces like FAITH/VOID. “Venues have more to worry about than noise complaints.”

In response to this difficult situation, Tanner, along with the Toronto Music Advisory Council (TMAC)—comprised of musicians, venue managers, and festival operators—are actively trying to protect Toronto’s DIY communities by pursuing a pilot project that will offer them city-owned space at a reduced cost.

TMAC’s efforts are being modeled after places like Paris and Seattle, where decades of high rents have led councils to hand DIY organizations the keys to city-owned buildings that would otherwise be sitting empty. It’s not hard to imagine a similar program in Toronto. According to Tanner, there are more than 5,000 vacant city-owned properties, and TMAC wants the city to give DIY organizations up to five years of stable access to those spaces.

Despite the promise of stability, Tong isn’t sure he would participate in the city-owned pilot if given the opportunity. “I think it’s great the city wants to get involved, but what we were trying to do with FAITH/VOID exists outside of that,” he says. “We weren’t waiting around for permission. We were making it happen because we had to.”

That approach may no longer be tenable in a city where surges in land value have led to closure after closure of beloved DIY venues, from SHIBIGBs to Soybomb to Double Double Land. DIY communities have to be strategic if they are interested in surviving the vagaries of an increasingly dense city that values economic activity above all. Put another way: in Toronto, you can’t get away with what you used to.

“You have to have a risk lens that you didn’t need twenty years ago,” says Jones. “Get a sound meter, do soundchecks, put limits on the soundboard. You have to think about the noise of people spilling onto the sidewalks, the rideshares dropping people off. If you’re operating a DIY venue, you have to be very careful.”

Being careful didn’t help Tong. He made sure concerts were held within a reasonable time. He developed relationships with his immediate neighbours, leaving them his phone number so they could work issues out together. “In a city, you’re sharing space,” he says. “I don’t think that it’s my right to make noise. I’m not entitled to disturb whoever I want.”

When he was hit with a noise complaint, Tong’s instinct was to reach out. “I wanted to speak directly to those neighbours and come up with a solution together,” Tong recalls. “I wanted to have a chance to explain to them I wasn’t just throwing loud parties.”

Instead, bylaw officers arrived at FAITH/VOID to enforce the infraction.

After FAITH/VOID’s noise infraction, Tanner offered to intervene, but the process of mediation, sorting out the fines, and getting approval to reopen the space for concerts took too long. Tong found himself at a crossroads, faced with the threat of major fines and being shut down outright. “Do I expend more energy, more money and put myself in a more precarious situation by involving myself with the authorities of Toronto?” he wondered. The burnout eventually led him to shutting down FAITH/VOID before moving to the UK. “I had to make a decision based on my wellbeing,” he says mournfully.

In a night in early July, the overgrown baseball diamond at Riverdale Park East was filled with ravers in cloth masks, pulsing to electronic basslines while carefully keeping six feet apart.

Inspired by the safety measures put in place during Black Lives Matters protests, the dance party organized by Lotion Magazine was planned with strict physical distancing protocols, with all proceeds going to Black Lives Matter Canada and Rainbow Railroad. Part rave, part protest, the party featured DJs familiar with Toronto’s DIY scene, like Korea Town Acid and Chippy Nonstop—artists willing to experiment with new formats in response to COVID-19.

The pandemic has added another dimension of precarity for Toronto’s artist and music scenes, which have been hit particularly hard by the pandemic and its restrictions on live performances.

“When it came to social distancing, we walked through and marshalled to make sure people weren’t too close” says one of the event organizers, a local artist who goes by Geist. Afraid of being shut down early, noise considerations were built into the planning of the event. “Riverdale is structured like a cone,” says Geist. “Sound travels up and not out, and it’s right beside a highway, so the noise was absorbed.” The party was also planned to end at 11:00 p.m., in accordance with an archaic and selectively applied bylaw that determines when people are legally allowed to be in the park.

“When the police came, we were already packing up,” says Geist, laughing. Giddy from the success of his last event and the potential of creative and safe ways to gather during the pandemic, he’s already planning more outdoor events.

The event was a testament to the stubbornness of Toronto’s DIY communities. Despite the looming reality of rising rents, the ever-present spectre of noise complaints, and the existential threat of a global pandemic, many aren’t ready to give up on Toronto just yet.

“FAITH/VOID may have closed, but it happened before, and it will happen again,” Tong says. “It doesn’t matter how long spaces stay open. The most important thing is that someone cares enough to keep them going.”