The bad news from Ontario colleges came slowly, then all at once. In October, nine months after the federal government put a cap on international students, Seneca Polytechnic announced it was shuttering its Markham campus. A month later, Sheridan College suspended 40 programs. In January, Mohawk College cut over a hundred staff members, St. Lawrence College discontinued almost 40 percent of its offerings, and Centennial suspended 49 programs—axing everything from construction project management to court support services to journalism.

The international students and their sky-high tuition fees were gone. In their absence, post-secondary education was crumbling.

The same week as the Centennial announcement, across the GTA on a street corner in Brampton, a group of students and former students were gathering together for the last time.

Since August, the demonstrators had maintained a 24/7 encampment on the edge of Highway 410. When I visited on a frigid day earlier in the winter, mats covered the ground and sleeping bags ringed the periphery of a tent while students spoke about their experiences in Canada, their breath visible in the cold air. A sign reading “Justice for our workers” hung over the entrance.

The protestors had come from India to Canada with the hopes of making it their home. Now a backlash against international students and a series of immigration policy changes—some intentionally targeting students, others which incidentally made their path to permanent residency in Canada more difficult—had left them with a dwindling set of options to remain in the country. To the students, it felt like they had gambled everything on making a life in Canada. And then someone had swept in and just changed all the rules.

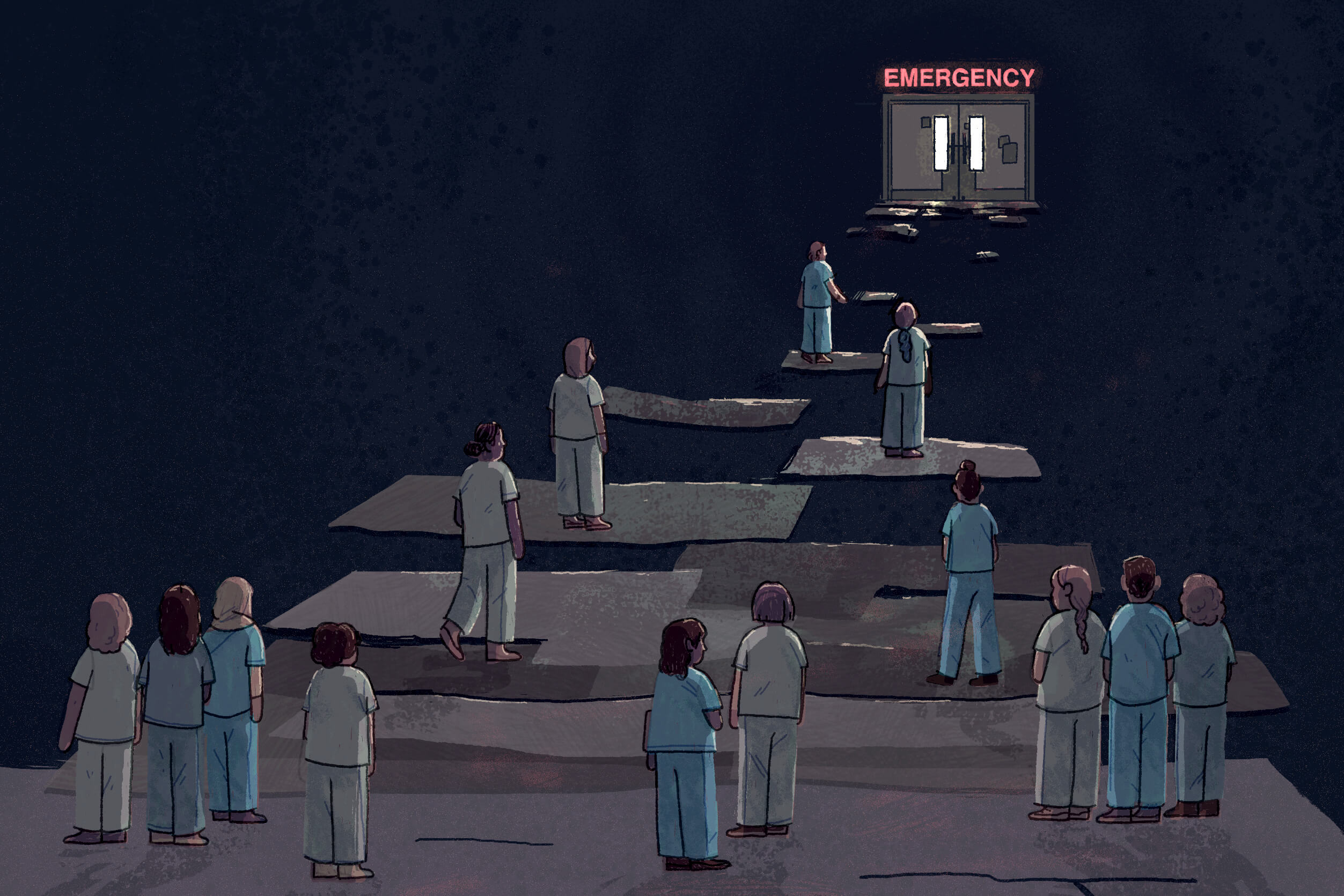

Across Canada, more than 200,000 former international students—people who came here under very different policies and in a very different political environment—will have their post-graduation work permits expire by the end of 2025. Some will go further into debt to re-enroll in a Canadian institution, doubling down on their bet in the hopes of making their application more attractive with an advanced degree. Some are now on visitor visas to temporarily remain in the country. Some have claimed asylum, counting on the lengthy process to buy them time in the country that’s now home. Some may even go underground. But most will simply be forced to return to their countries of birth, leaving behind jobs and families and opportunities.

Join the thousands of Torontonians who've signed up for our free newsletter and get award-winning local journalism delivered to your inbox.

"*" indicates required fields

The demonstrators were pushing for an extension to their post-graduation work permits (PGWPs) as well as a clear pathway to permanent residency. More than that, the protest was their attempt to make themselves heard. If they could just tell their stories and introduce themselves to a country that they could feel was turning against them, perhaps they could push back against the tide?

But by late January, after 143 days, it was clear that events had moved past them. Trudeau had announced his plan to resign and prorogued parliament. The MPs who had met with them before had largely disappeared. And after months in the cold, the students were worn out.

The day they tore down the encampment, protestors hugged one another as they moved through the frigid air, taking down the tarps and tents that had housed a much-needed community. “We have become a kind of family,” says Novjot Salaria, a York University graduate who left her IT job in Delhi to move to Canada. She has a good job at a bank now, but will be forced to leave it all when her work permit ends in September. It was hard not to feel like they had failed. “Even after so many days we were not able to make our voices heard.”

At the conclusion of a decade-long era of international student policy, as the government and post-secondary institutions deal with the wreckage, it’s worth grappling with the program’s complex legacy. The era will leave lasting changes in communities like Brampton that have struggled to absorb so many newcomers. The cuts at colleges and universities will continue to shape post-secondary education for years to come. Public opinion around immigration has shifted in ways that are yet to be fully understood. In all the discussion, it’s perhaps unsurprising that the fates of the individual students themselves—always an afterthought in a system designed to wring as much value from them as possible—have largely been shunted aside.

“Every time I felt like giving up, I reminded myself of the land we sold.”

On his worst days, when he was homesick and depressed and ready to give up on his dreams of a life in Canada, Mehakdeep Singh would think about his grandfather’s land. Some of his fondest childhood memories were of helping the family harvest cotton and sugarcane on that patch of farmland in Punjab. Now the land was gone, sold in order to raise the funds necessary to send him to college in Ontario. “Every time I felt like giving up, I reminded myself of the land we sold,” says Singh.

Singh is a bright-eyed 26-year-old with a wispy beard. The proceeds of the family farm bought him a place at Fleming College in Peterborough in 2018, where he studied to be a heating, refrigeration, and air conditioning technician.

The fact that so many people were similarly willing to sell the family farm to pay for a college program in Peterborough is, if nothing else, a testament to the efficacy of a decade of Canadian messaging.

In 2014, under Prime Minister Stephen Harper, the federal government created a roadmap to expand Canada’s promising international education system. The document laid out a strategy to double the number of international students within the next decade. That approach, supercharged under Trudeau, was an attempt to bring tuition money to post-secondary education institutions that were already being slowly bled dry by provincial underfunding. But it was also an exercise in nation-building. “As Canada’s working population ages and retires, there are not enough candidates to replace them,” the report reads. What if you could bring over young strivers from around the world, train them for the Canadian labour market at Canadian institutions, acclimate them to this country’s culture, and then have them transition seamlessly into much-needed professional jobs? And what if you could do it on the cheap, without investing in the costly settlement process that usually accompanies immigration?

“The International Student Program was a great program for the Canadian government,” says Gautham Kolluri, an education agent from India who once worked as a recruiter for Conestoga College and Mohawk and has long been critical of the worst excesses of the industry. “Why? Because the government doesn’t have to spend a dollar bringing in all those immigrants.”

Instead, people like Singh were paying for it. When he finished his program in Peterborough, Singh moved to Brampton and began looking for work. By 2021, he was working as a security guard manager at parking lots and Shoppers Drug Mart. At that time, during the heart of the pandemic, international students/workers like him were being hailed as “pandemic heroes.”

“Whether as nurses on the pandemic’s front lines, or as founders of some of the most promising start-ups, international students are giving back to communities across Canada as we continue the fight against the pandemic,” then-Minister of Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Marco Mendicino tweeted in early 2021. “Our message to international students and graduates is simple: we don’t just want you to study here, we want you to stay here.”

That messaging was not an accident. “They didn’t say it to be nice,” says Dale McCartney, an assistant professor at University of the Fraser Valley who studies international education. “They said it because they were recruiting students in a competitive market, and they wanted to maximize the number of students they could get.” Every politician who wasn’t lying to themselves understood the obvious truth: no foreign student was going to sell the family farm and go into generational debt because of the intrinsic value of a Centennial College certificate. The winking promise of a pathway to permanency was the entire selling point.

That pitch was enormously successful. Universities and colleges were able to bring in millions of dollars in tuition—the education of countless Canadian-born students subsidized by the classmates next to them working night shifts as security guards. Businesses were able to get access to cheap labour. And as the international student industry exploded, surpassing lumber or autoparts in the Canadian economy, the country enjoyed a massive transfer of wealth from places like rural India.

The one group that, frustratingly, refused to prosper as designed was the students.

By 2021, it was more than clear that things had gone awry. Education agents were making dishonest sales on behalf of Canadian colleges and universities. Unscrupulous employers were exploiting students hamstrung by limitations on their work visas. Students were depressed, and there were several cases of suicide. By then, it was obvious that the system was enormously exploitative. It kept growing anyway. In 2022/23, the number of international students enrolled in college and universities increased by 16 percent from the previous year.

All of which has made the sudden, haphazard dismantling of the system over the last year—with seemingly little thought paid to the students who had bet everything on a future here—all the more jarring to witness.

When the government announced the first cap on students in early 2024, their stated reasons were “to better protect international students from bad actors and support sustainable population growth in Canada.” The real reason seems far simpler. In the midst of a housing crisis, immigration had become a political liability. And international students are among the least powerful, least popular constituencies in the country.

A much-covered Environics Institute poll from last fall found that for the first time in a quarter century, the majority of Canadians said there was too much immigration. But the details of that poll are almost more telling. While 73 percent of Canadians said the government should prioritize immigrants with specialized skills, just 27 percent of respondents said they should prioritize international students.

“I think the Liberals see them as a relatively easy scapegoat,” says McCartney.

In a statement to The Local, a spokesperson for Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada said that applying to study at a Canadian institution provides applicants with only temporary—not permanent—status. “It is important to note that having a temporary status does not guarantee a transition to permanent residence,” the statement said.

It added that IRCC continues to work to “address the ongoing challenges faced by international students.”

The winking promise of a pathway to permanency was the entire selling point.

For former students like Singh, watching that process play out has been its own kind of education. “I think they are playing dirty politics,” he says. “Saying immigrants are the problem for the housing crisis, immigrants are the problem for the job crisis?”

Singh’s work permit expired in July 2024 and he’s been on a visitor visa since. After six years in the country, working, paying taxes, contributing to a pension system he has no right to access, he’s now borrowing money from his parents again and trying to fight off depression. It’s hard for him to even contemplate what he’ll do when the visitor visa ends. “I can’t think of that,” he says. The idea of being forced to leave the country after having spent all his family’s resources on Canadian-specific job training is too much to bear.

The assumption that motivated the way this international student system was constructed—the idea that Canada is so desirable that you could attract anyone in the world without much investment or care in their wellbeing—also undergirds its dismantlement.

“I believe that the government thought that the desire to come to Canada was so enormous and so permanent that they could always fill whatever spots they wanted,” says McCartney.

That is not the case. According to recent analysis from the online international student marketplace Applyboard, the government’s changes to international student policy have already had a larger impact than intended. The government’s aim was to reduce the number of study permits approved by 35 percent. The Applyboard analysis says approvals went down by 45 percent in 2024.

Kolluri, the education agent, says the previously booming business of selling Canadian education is dead. In India, the education agents that once sold Canadian education on every street corner have been closing up shop, or else pivoting to promoting post-secondary education in Europe. Kolluri has closed offices in India, as well as the Philippines. “We hardly have any students,” he says. “Changing policies at such a lightning speed within a span of two months has completely destroyed the reputation of Canada.”

Those changes will have lasting effects. Because despite this current wave of anti-immigration sentiment, the problems that international students were supposed to address have not gone away. Canada remains an aging society without enough workers. We need immigrants. We need them to thrive. And we are in direct competition with countless other countries that need the exact same thing.

At the same time as the students in Brampton were dismantling their encampment and the province’s colleges were imploding, a bigger, more lasting story continued outside the narrow confines of Canadian political discourse. Finland began a campaign to attract much needed foreign labour and South Korea struggled to bring in enough workers to staff its shipbuilding industry. Syrian migrants returning to their home country prompted fears of labour shortages everywhere, from German hospitals to Turkish textile factories. Japan ramped up a desperate recruiting effort to bring in nurses from Southeast Asia, Croatia tried to retain foreign workers by offering them unemployment benefits, Greece planned to overhaul its entire immigration system to attract more migrants, and Canada’s Atlantic provinces still didn’t have enough construction workers. Immigration cuts, they complained, would only make things worse.

The enduring story of immigration in the 21st century will be of countries like Canada fighting to attract the best in the world. The story in Brampton in January 2025 is of the government pushing out people who are desperate to stay.

Despite dismantling the encampment, the former students in Brampton say they’re not giving up. “This one thing is coming to an end, but we will continue,” says Novjot Salaria. The group is planning more demonstrations, trying to think up new ways to tell their story. Despite an upcoming federal election in which no party seems likely to champion international students, she can’t help but think Canadians can be convinced. The way she and her fellow students are being treated just doesn’t make sense. “Deporting or asking such a large volume of workforce to leave the country is not sustainable,” she said. “Do they have a plan?” They don’t. But whatever the plan becomes, people like Salaria and Singh will not be a part of it.

__

The Immigration Issue was made possible through the generous support of the WES Mariam Assefa Fund. All stories were produced independently by The Local.