If he had his way, Ashwyn Singh would stay as far away from social media as he possibly could. But the 28-year-old software developer turned stand-up comedian has to log in to his Instagram account to promote his upcoming gigs. When he does, he tries to post what he can and get out, resisting the addictive lure of doomscrolling—but he still gets caught up in it from time to time.

In the last six or seven months, Singh has come across more and more online content denigrating Indian immigrants living in Canada. The social media posts leave an unpleasant impression. Under an Instagram video of young Sikh men dancing outside the Eaton Centre, for example, he’ll find spiteful comments ridiculing the young men and telling them to take their behaviour back to where they come from.

The immigrants targeted in these videos “might be dancing and being a nuisance,” Singh says. “But being a nuisance and being a racist are not the same level of crime.”

Singh’s seen and heard enough of these posts to incorporate them into his stand-up routines, teasing out the ironies and contradictions of anti-immigrant sentiment. “It’s such a silly thing to fight [about] when you realize your labour market is declining, as is your birth rate,” he says.“That’s why immigrants are being allowed into the country.”

Singh isn’t the only one noticing a dehumanizing new wave of online hate against Indians. Videos circulate online of immigrant-dense suburbs like Brampton, where bystanders are often filmed without their consent, the videos captioned, “Is this Toronto or India?” Tim Hortons is mocked as “Singh Hortons,” given the number of Indian international students working as servers. Viral misinformation about Indians defecating at Wasaga Beach prompted the local mayor to weigh in, firmly denying the events and warning against baseless rumours. Posts openly deride food delivery drivers taking their e-bikes home on local transit, trying to make ends meet with gig work.

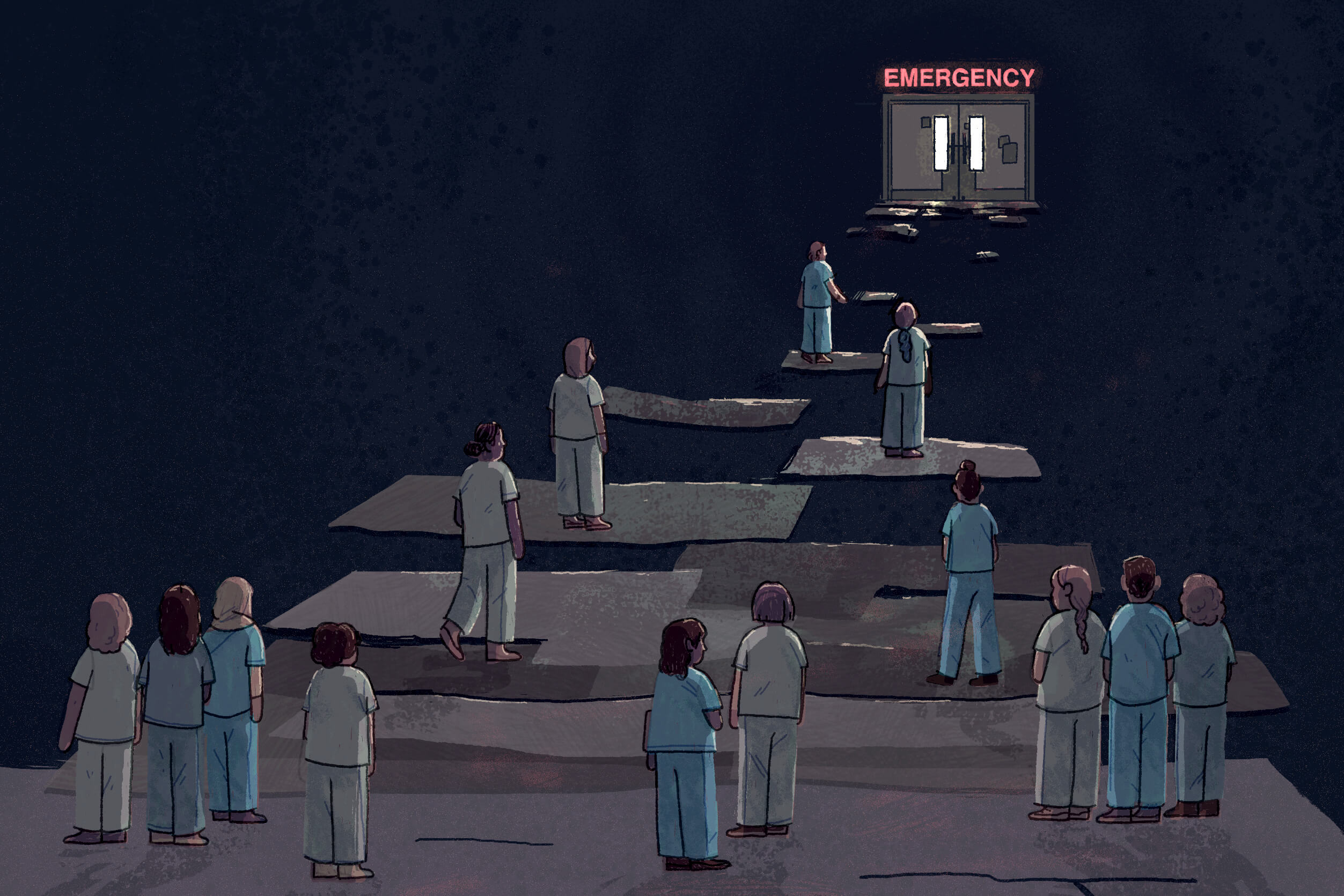

From a meme Instagram account that perpetuates stereotypes to far-right groups spreading conspiracy theories, there’s been a dramatic rise in viral content over the past year that disparages Indians. This has grown into political scapegoating: newcomers and international students from India have been blamed for a slew of systemic issues including the housing crisis, unemployment, and an overcrowded health care system. It’s a familiar pattern across history, to blame immigrants or specific ethnic groups for the social ills caused by poor leadership, economic downturn, even global pandemics.

Join the thousands of Torontonians who've signed up for our free newsletter and get award-winning local journalism delivered to your inbox.

"*" indicates required fields

On the global stage, Canada has long been lauded for its multicultural society that welcomes immigrants of all sorts—from economic migrants and skilled labourers to political refugees and minorities fleeing persecution. This image of Canada became even more popular when compared to the exclusionary rhetoric espoused by President Trump during his previous administration, while Canada was welcoming of asylum seekers. But this image has been tarnished by recent federal policy announcements that cap student permit applications, reduce immigration targets, and mandate most provinces and territories to cut economic immigration programs by half.

Within Canada, there’s always been some acknowledgement of an undercurrent of anti-immigrant bias. Each cohort of newcomers, right from the early foundations of the country, has faced a unique set of prejudices—from ignorant remarks or systemic discrimination to racist outbursts or violent attacks. The Komagata Maru incident of 1914 is perhaps one of the earliest documented acts of discrimination against South Asians, when a boat of 376 prospective immigrants was denied entry to Canada because of colonial ideas of race and exclusion that sought to limit South Asian immigration to the country. Similar cases of racially restrictive immigration policy can be traced further back, aimed at Chinese, Japanese, and Black newcomers to Canada, until the establishment of the country’s Multiculturalism Policy in 1971.

The current online onslaught is the latest incarnation of anti-immigrant rhetoric, this time targeting Indians, and by extension South Asians. Community advocates have warned that last year saw an online shift toward “spreading conspiracy theories and sowing hate towards South Asians and Sikh communities in Canada,” adding to misinformation and harmful narratives about immigrants. This online shift follows a series of violent incidents over the last few years fueled, at least partially, by hate. Take, for example, the 2020 stabbing of cab driver Balbir Toor in Winnipeg, or the Islamophobic killing of the Pakistani-Canadian Afzaal family in London, Ont., in 2021.

These Canadian findings mirror a larger, global phenomenon. According to the US-based non-profit Global Project Against Hate and Extremism, “slurs directed at South Asians on fringe platforms have been rising exponentially, as the community is blamed for replacing white people.” The organization reported seeing a “monumental spike” in racist rhetoric that then trickles down to mainstream platforms such as Facebook and Instagram, normalizing bigotry and leading to real-world repercussions. Although the actual number of reported hate crimes remains small, according to StatsCan figures, hate crimes against South Asians rose by 143 percent between 2019 and 2022. In a survey by the Canadian Race Relations Foundation, a quarter of South Asian respondents reported having experienced discrimination or harassment in 2022.

Experts say that much of the blame lies with the government and other authorities that have not provided adequate settlement support for newcomers to Canada. It’s a vicious cycle between public sentiment and policy: misinformation, hate mongering, and poor policy choices stoke public animosity towards vulnerable communities, which in turn prompts further reactionary policy decisions.

For years, international students, many of whom are from India, have been steadily recruited to Canadian colleges, paying fees four and five times the rates of their domestic counterparts to make up for the funding lost in provincial cuts. India now also supplies the second-highest number of temporary foreign workers to Canada, after Mexico; these workers are hired to do menial labour by employers looking to pay low wages. But neither colleges nor employers have offered services to help these newcomers navigate life in Canada. They rely instead on their peers, community members, or Facebook groups to find housing or jobs. Many of them ended up in substandard housing or work conditions.

This has made Indian newcomers hypervisible. They serve coffee and doughnuts at Tim Hortons, work as security staff at buildings, and deliver food using e-bikes—and then are blamed for stealing jobs. They’re criticized for taking up housing stock in cities, despite facing a crisis of substandard and exploitative housing themselves. These prevailing ideas can result in discrimination—but newcomers rarely have any legal recourse in such situations.

The South Asian Legal Clinic of Ontario started to receive more calls in the spring of 2024, says the organization’s executive director and lawyer Shalini Konanur. People calling in were primarily temporary residents, and were reporting a range of hateful interactions, from racial slurs to threats of violence.

“Comments were being made while they were looking for housing. Even in person, comments were being made when they went to the food bank [about using the city’s resources]. Or generally going out and about in the city,” says Konanur, adding that such interactions were fuelled by the false narrative that newcomers were sapping local resources and bringing up the cost of living in Toronto.

“Social media has allowed people to say pretty hateful things without any repercussions.”

Konanur herself encountered verbal harassment in October 2024.

“I parked my car and was going into a shopping mall, and somebody yelled, ‘Go back to your country.’ Which—I’m born and raised here,” she says.

Although today’s anti-immigrant rhetoric is closely tied to blaming international students and foreign workers for the affordability crisis, you only have to look back at the pandemic to see how other racialized groups become a target of hate, whether online or offline, adds Samya Hasan, executive director for the Council of Agencies Serving South Asians (CASSA). At that time, South Asian communities were being criticized for having a higher rate of COVID infections, even though those infected were primarily employed as frontline workers in the health care and retail sectors. Simultaneously, a campaign of anti-Asian hate was growing, rooted in accusations that the virus was Asian or Chinese. This only made its way out of public discourse following concerted efforts by activists and non-profits to counter the misinformation and encourage victims to report hate incidents.

“The white supremacy ideology,” the same sentiment that throughout Canadian history has undergirded previous waves of xenophobia and racism, going back even to a time when Irish and Italian immigrants weren’t considered white enough, “needs a scapegoat, to blame the issues of the day, the social problems, the country’s problems [on] certain communities that are vulnerable at the time,” she says.

The reality is that life is hard for everyone, and that xenophobia isn’t new, says Konanur.

“The cost of housing and food, the stagnant wages—everyone is struggling… When people are struggling and the economy is not doing great for them, one of the immediate targets is immigrants,” she says. “Globally, things are happening around the world that [are] giving people permission to say things they would not have said before.”

All of this is happening at a time when social media platforms are relaxing their rules around what’s permitted online. When Elon Musk acquired Twitter in 2022, he slashed jobs and loosened content restrictions. Mark Zuckerberg, CEO of Meta (which owns Facebook and Instagram), recently announced the end of fact-checking and removal of speech restrictions, in a move widely seen as part of the tech industry’s decision to align themselves with the agenda of the new Trump administration.

“Social media has allowed people to say pretty hateful things without any repercussions. People are hiding behind their handles,” Konanur says. “For all the good of the internet, the progression of hateful commentary has been worrying.”

“If it’s happening in front of you, you can go and speak out against the injustice. Online, it feels like all you can do is watch.”

It’s hard to know how much damage has been done by the rampant rise of online hate in recent years, particularly as fringe anti-immigrant and white supremacist ideas become more and more mainstream. But it has materially changed the experience of being an Indo-Canadian online.

Looking for a distraction after work one day late last fall, Mauli Thakkar was scrolling through Instagram. Thakkar, 27, immigrated from India in 2017 for her education, and now works as a digital account manager with Google Canada. In the video playing on loop before her eyes, randomly thrown onto her feed by the algorithm, an elderly South Asian couple was out for a walk when they were approached by a white passerby yelling at them to go back to where they came from.

“It just makes you feel really sad,” says Thakkar.

The post came at a time when news headlines were dominated by reports of clashes within the Indian diasporic community outside a Hindu temple in Toronto, fallout from the tensions between India and Canada after Prime Minister Trudeau accused the Indian government of being involved in the killing of Canadian Sikh leader Hardeep Singh Nijjar. To anyone ignorant of the events, the news just looked like chaos and violence among Indians in the GTA.

“Many [people outside the Indian community] don’t understand what’s going on. And then they blame an entire country. It’s unfair,” she says.

“I read the comments,” adds Himani Limbachiya, 30, a friend of Thakkar’s who immigrated to Canada as a teenager and now works in graphic design. “It’s good to know what people are saying. How people think about you.”

Exposure to this content can be draining, says Konanur. She recommends seeking out agencies that serve the community and provide mental health support and other resources, including advocating on behalf of people with temporary immigration status. And there are groups working to combat misinformation and fight this wave of hate, just like the last one.

But there’s a sense of helplessness that comes with watching this new wave of hate unfold every time you open up an app, hoping to distract yourself or share something with friends or goof off for a few minutes. “If it’s happening in front of you, you can go and speak out against the injustice,” says Thakkar. “Online, it feels like all you can do is watch.”

__

The Immigration Issue was made possible through the generous support of the WES Mariam Assefa Fund. All stories were produced independently by The Local.