I first noticed the signs in early November—flyers posted on Marlee Avenue hydro poles that read, “As a cyclist, it’s heartbreaking to see our own neighbours advocating for policies that will get us killed.”

I had just moved into the neighbourhood near Eglinton Avenue West and Allen Road in October, and I initially chalked the action up to the debate over Bill 212, the recently passed provincial legislation that aims to remove bike lanes from University Avenue, Bloor Avenue, and Yonge Street. But within a few days, I began to see bright red signs—“Keep Marlee Avenue Safe! No Lane Reductions! No Bidirectional Bike Lanes!”—popping up on nearby lawns and in business windows.

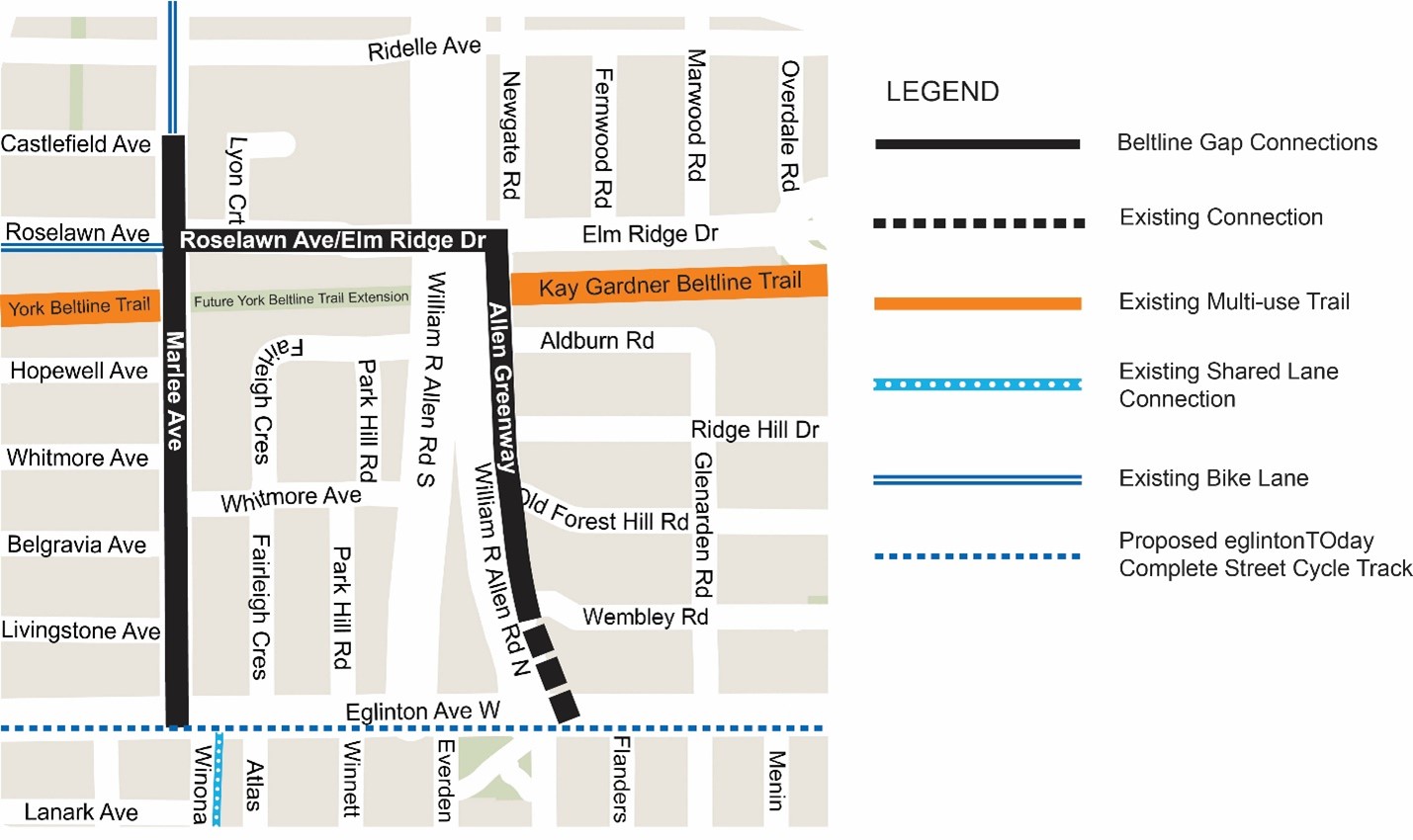

The project creating a rift in my community is a modest, six-block stretch of proposed bike infrastructure. In June, the City approved the Beltline Gap Connections project, which will create a safe cycling and pedestrian route over the Allen Road Expressway to connect the York Beltline and Kay Gardner Beltline trails. The project also includes cycling safety improvements on Marlee Avenue, Roselawn Avenue, Elm Ridge Drive, and the Allen Greenway multi-use trail.

In the months after the approval, a group of homeowners and small businesses along the short stretch of Marlee Avenue between Roselawn and Eglinton began petitioning to “keep Marlee Avenue safe.” The group opposes the bidirectional bike lane proposed for the west side of the street, claiming that it will increase accidents, slow bus services, decrease property values, and cause “significant mental health stress” to the property owners. While more than a hundred doctors and researchers were signing a letter to Doug Ford endorsing bike lanes, at the health care clinic and pharmacy on Marlee Avenue, there were not one, not two, but three anti-bike lane signs.

At a moment when Toronto cyclists have been focused on trying to save the Yonge, Bloor, and University bike lanes from Doug Ford’s Bill 212, this other bike lane drama has been quietly unfolding on this mixed-use residential and commercial street in the former borough of York. And despite being far from the debates taking place downtown, the fight in this corner of Toronto is fuelled by the same sentiments and fears—some based on questionable interpretation of fact, others entirely imaginary—that seem to emerge whenever even the most modest cycling infrastructure is proposed.

For people who bike in the area, the changes are just common sense. Isaac Berman, a 28-year-old computer engineer, has been regularly biking from south of St. Clair West to his grandmother’s home on Marlee for the last six years. Like many Torontonians, Berman doesn’t own a car, and relies on transit or his bike to get around. He says the section without a bike lane on Marlee Avenue, from Eglinton to Roselawn Avenue where bike lanes extend north, is “the scariest, worst place to bike” on his entire ride.

The project will close this approximately 475-metre gap, completing a critical link in the broader cycling network by connecting Marlee to Winona Drive on the south side of Eglinton. Recent cycling improvements on Winona have created a “beautiful, straight north-south cycle route that starts at Wellington and goes, in principle, all the way up to Lawrence,” says Andrew Ilersich, an area resident who uses the route to commute downtown.

“But you’ve got this horrible little gap between Eglinton and Roselawn, and because I don’t have many other choices, I just bike there anyway.”

Running parallel to the Allen Expressway to the east and Dufferin to the west, Marlee is exactly the kind of lower volume, secondary street on which Doug Ford and his Minister of Transportation Prabmeet Singh Sarkaria have repeatedly stated bike lanes ought to be. A cursory glance at a map of the area reveals there are no other secondary streets near Marlee that would provide a continuous route north to Lawrence.

Ilersich calls this project “a huge step in the right direction” because it signals that the City is thinking about a connected bike network, rather than just bike routes.

For the bike lane’s opponents, however, those considerations are secondary to their worries about safety and congestion. Anthony Kyriakopoulos, Peter Triantafillou, and Yarema Yaremchuk are representatives of the group opposing the bike lanes. Kyriakopoulos has lived in the neighbourhood since 1979 and Triantafillou since 2002. Triantafillou also owns a small business on Marlee and leases space in the same building to a variety store. These two businesses, plus a nearby health care clinic and a dry cleaner, are the only commercial properties affected by the changes.

Kyriakopoulos says that their petition, which has garnered about 340 signatures between their door-knocking efforts and digital version, was started before the uproar began with the province. But intentionally or not, their materials parrot provincial rhetoric about lane reductions and promote the false narrative that car traffic will be negatively affected.

When the province talks about lane reductions, it specifically refers to cases where a lane of car traffic is removed to construct a bike lane. That’s not the case on Marlee.

“There will be no lane reductions on Marlee Avenue,” clarified Laura McQuillan, a senior communications advisor for the City in an email. In fact, lane widths are simply being narrowed to meet the City’s guidelines, a change known to discourage speeding. The petition also makes the incorrect claim that the southbound left turn lane from Marlee onto Eglinton West will be removed.

Responding to other concerns in the petition, McQuillan stated that the bike lane and widened sidewalk on Marlee Avenue are based on municipal and provincial standards and guidelines. Bus turning movements are modelled and reviewed by the TTC to ensure buses are properly accommodated, and snow storage space will be available in the buffer areas between the sidewalk, cycle track, and vehicle lane.

Join the thousands of Torontonians who've signed up for our free newsletter and get award-winning local journalism delivered to your inbox.

"*" indicates required fields

Importantly, the project is to be entirely installed within the public right-of-way, which includes the road, sidewalk, and the portion of every front yard that is actually municipal property.

In his May 28 deputation at the City’s Infrastructure and Environment Committee, where the Marlee issue was discussed along with several other cycling network projects, Triantafillou noted that drivers on Marlee are “really aggressive” but worried that his kids might “walk out the door and get smoked by a bike.”

That fear is likely misdirected. According to the Beltline Gap Connections website, the project area has seen 343 collisions involving motor vehicles in the past 10 years—including one pedestrian fatality.

One afternoon this November, I visited the Marlee Avenue route from Eglinton to Roselawn with Kyriakopoulos, Triantafillou, and Yaremchuk. As we walked, the trio pointed out numerous points on the street where they believe parking, properties, garbage collection, and ease of exiting onto Marlee will be adversely affected by the new bike lane and widened sidewalk. Kyriakopoulos demonstrated by measuring heel-to-toe the various points where he contends the street is too narrow to accommodate the project, and showed me that he will no longer be able to park a car in the space in front of his two-car garage. He also surmised that hydro poles would need to be moved, which would cost an exorbitant amount of money.

The City said it does not anticipate moving the poles and that changes would be made to the road and sidewalk to best accommodate the project and meet the standards required by the Accessibility for Ontarians with Disabilities Act. In addition, the work is being bundled with planned “state of good repair” work in the area, which the City calls “a once in a generation opportunity to make significant changes.”

A major sticking point for the opposition group is that to get a car from a driveway or garage into the street, drivers would have to back out through a bike lane. The petition describes a driver in this scenario as first needing “to check for pedestrians. Next, they would need to look for cyclists coming from both directions due to the bidirectional bike lane. Finally, they would need to back up onto the busy Marlee Avenue traffic, which presents a complex and potentially fatal situation.”

But this isn’t how driving works, says Scott Marshall, former director of training at Young Drivers of Canada, the country’s largest driver training organization. It’s not about scanning for pedestrians, then cyclists, then cars.

“You’re looking for [all road users] at the same time,” he says. “You just have to look further up the road.” If backing out onto Marlee is a challenge, Marshall adds, the solution might be as simple as just backing into your driveway instead.

The bike lane’s opponents are unconvinced by any of these arguments. They’ve emailed their petition to local Councillor Mike Colle, Mayor Olivia Chow, local MPP Robin Martin, the Premier, and the Minister of Transportation.

According to McQuillan, when the detailed design is advanced, the City plans to send follow-up letters to residents in January 2025. Residents will then have the opportunity to meet with staff to review any right-of-way impacts.

Comparing the reality of the plan for this small bike lane in my neighbourhood with the heightened tone of the opposition, it was hard not to see larger cultural divisions at play. Animosity between bikes and cars in Toronto is a tale as old as time, often inflamed by misinformation or lack of information. Bike lanes make easy targets for drivers frustrated by Toronto congestion and for property owners who feel unheard.

But the nature of cities is one of constant evolution. Populations grow, housing needs change, and, eventually, societal norms shift in response.

Densification along Eglinton is inevitable with the opening of the long-awaited Eglinton Crosstown. Indeed, a 43-storey condo building is planned at the northeast corner of Eglinton West and Marlee. The building will consist of 442 units, retail on Eglinton, and no residential car parking. Instead, there will be six spaces for visitors and parking for 487 bicycles.

Sharing an article about the development with me, Kyriakopoulos and Triantafillou scoffed at the idea that a tower of this size could exist without car parking. But the people—and their bikes—are coming whether they like it or not.

“You’re still going to have cyclists,” Marshall says. “They’re part of our community. They might live right next door to you—maybe they shop at your business.”

The future is coming for Marlee, with or without the bidirectional lane.