I’ve been anxious about the future. There’ve been so many things to worry about as I head into my last year of university—the job market, the costly apartment ads on Facebook Marketplace that crush my hopes of living alone, my desire for deeper companionship, and my doubts about studying journalism, which everyone keeps telling me is a dying field.

If this sounds like a conversation you had with me last year, I probably gave you a very defensive response, and I am sorry for that. (And I’m sorry for being defensive in general.) In moments of anxiety, I’ve scrawled out notes to myself on neon green Post-its, trying to reassure myself that everything will be okay and that I am doing my best. One summer, during the worst of my angst when I couldn’t find a job, I spent entire days in bed, scrolling, eating, and sleeping. By late August, the center of my mattress had become a perfect mould for my body, ready to welcome me back each time I managed to leave it. Subreddits, TikTok influencers, and career-focused Instagram pages fueled my fears that after four years of university, I’d end up working at McDonald’s.

As I get closer to finishing my degree, I’ve had complicated feelings about leaving university next year. I should be excited and proud to be approaching this milestone, yet those have not been my primary feelings. I get incredibly anxious when I realize that the stage of life I often thought of as the future is right here, about to begin.

Of course, previous generations have had similar feelings about approaching life after university. One day, your biggest challenge is waking up for an 8 a.m. class; the next, you’re staring down the question of what you’re going to do with the rest of your life. But young people today are, in some ways, navigating an even greater sense of uncertainty than their parents and grandparents did.

Ours is a generation whose formative years were spent in COVID lockdowns; we’re emerging into adulthood at a time of multiple crises—an affordability crisis, a housing crisis, a climate crisis, a trade war with the U.S. We are faced with uncertainty about big things, like the future of our social safety nets, our democratic institutions, and the impact of AI on our lives, as well as more personal concerns, like whether we have the right degrees, or whether we want to have children.

In all, it feels like for most of us born in the 2000s, the odds were rigged from the start. Yet lately, as I’ve been speaking with many of my peers to try to get a sense of what they’re thinking about the future, a different picture has emerged—one that isn’t nearly as bleak as the headlines and statistics suggest. In spite of it all, there’s hope and optimism. Many young Torontonians continue to imagine futures filled with bright possibilities. Hearing this from my peers has given me more reassurance than any of my Post-it notes. The Class of 2026, it turns out, is not cynical or nihilistic. Nor are we naive. Rather, as my peers and I return to school this month for the final year of our undergraduate degree, we’re facing the many uncertainties ahead of us with a pragmatic and constructive outlook.

Join the thousands of Torontonians who've signed up for our free newsletter and get award-winning local journalism delivered to your inbox.

"*" indicates required fields

The worries I’ve had are not unfounded. According to a 2024 report by the Wellesley Institute, a Toronto-based think tank, a single person would need to make more than $61,000 a year to thrive in the GTA. [The Wellesley Institute is one of the funders of The Local. This story was produced independently.] By comparison, a 40-hour workweek at the new minimum wage in Ontario of $17.60 per hour, effective this fall, would earn you less than $37,000. And that’s if you even have a job. The unemployment rate among Canadian youth, ages 15 to 24, climbed to 14.6 percent in July 2025. Everyone I spoke to, including 21-year-old Josephine Graham, agrees that this is worrying, but she still holds out hope.

I met Josephine at a book club I joined this summer to escape my small room in a shared rental in downtown Toronto. She’s double-majoring in anthropology and communications at the University of Toronto in Mississauga. She genuinely loves what she’s studying. She spoke to me about wanting to become a cultural anthropologist, a publisher, or a librarian. Even though these aren’t particularly lucrative jobs, she wants to do something she’s passionate about.

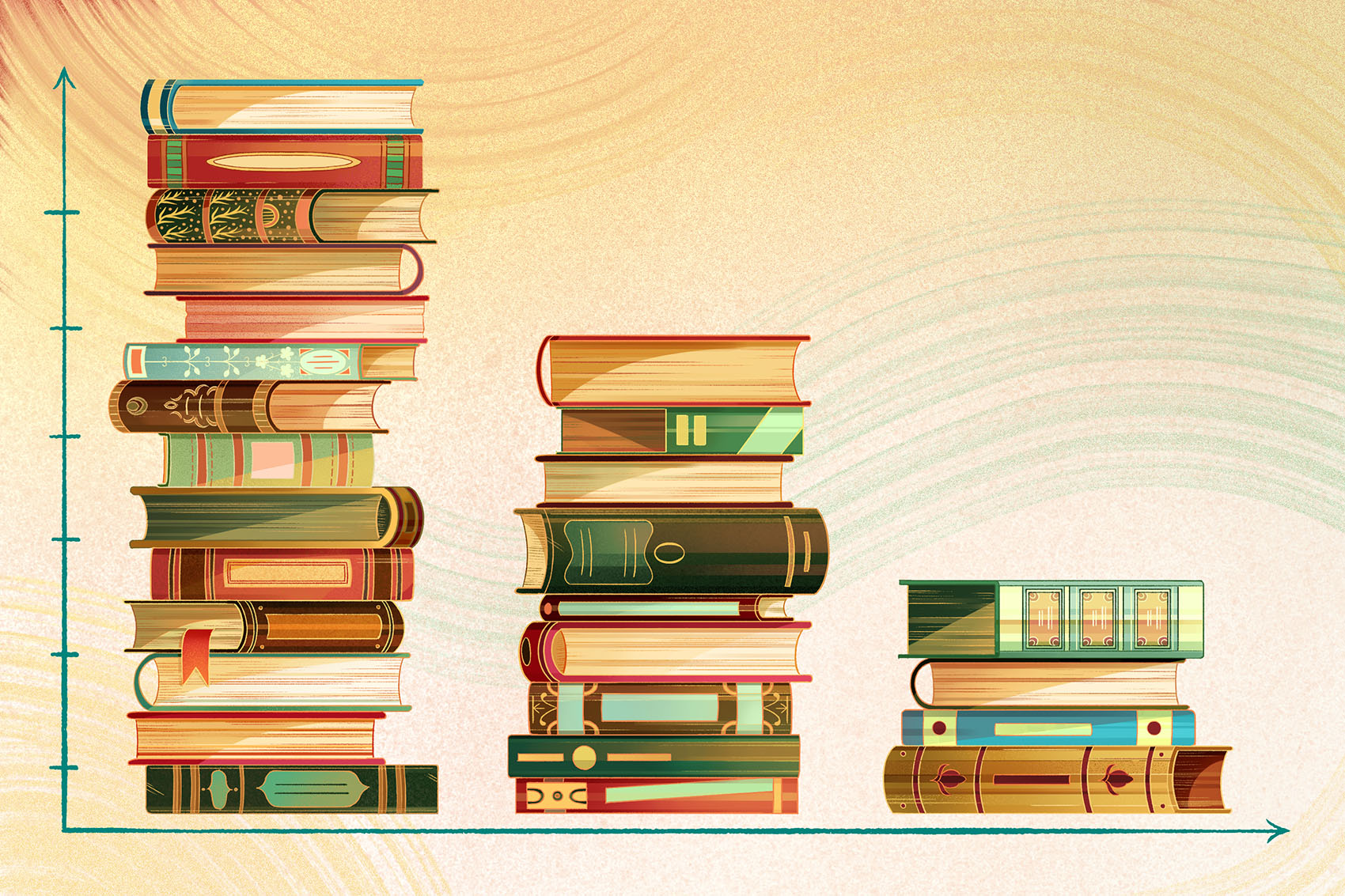

“I’ve never been interested in any of those high-earning occupations,” like in medicine, she said. It’s not just Josephine. In my admittedly unscientific survey, I noticed that other young people I spoke to, especially those studying non-STEM degrees, would choose passion over pay. I know some people may shake their heads at this, given that homelessness and food bank usage in the city have surged and the cost of living has skyrocketed. But the peers I spoke to aren’t oblivious to the harsh realities of life. Rather, most of them seem to value meaning and stability in their work over high salaries. This is a trend that was captured this summer by the Youth Employment Postcard Report, created by the Toronto Youth Cabinet with other non-profits. That report found that 75 percent of respondents said “a meaningful job must align with their passions, values, or sense of purpose.”

As Josephine explained, her goal is not to make a fortune, but to be comfortable. “I like the idea of a slow and quiet life. I would be happy with, just like, having the time to cook more or things like that…just being happy in the career that I have,” she said.

Surprisingly, during my conversations with young people about their future, housing did not come up as much as I thought it would, considering its painful cost. The average market rent for a one-bedroom in Toronto in 2025 is $1,715, up 60 percent from a decade ago. And the median age of a first-time homebuyer last year was 40, up from 36 in 2014. Yet it seems that many of my peers have become so resigned to the fact they may never buy a house that the desire just isn’t there. Instead, they want to improve their current living situations, like going from sharing a space with four roommates to finally living alone.

During the first heatwave of the summer, I went to Scarborough to talk to Janice Soro, a human biology student entering her final year at the University of Toronto this fall. On a Wednesday in late June, the campus was quiet. I met Janice at the campus food bank, where she volunteers. Her face is one of eight drawn with erasable markers on a large whiteboard in front of the room. Janice is passionate about sustainability and environmental sciences and would like to pursue a career in the field.

On paper, she seems to be doing everything right: good grades, involvement in campus life, good rapport with professors. But she recognizes it could be a while yet before she’s able to afford to live on her own. Janice lives in a rented room in a shared basement near campus. Her rent is $850 per month, and she describes her landlady, who lives upstairs from her, as a sweet old woman who always wants to help out. Still, her one goal after leaving school in 2026 is to move out.

“Ideally, I would have been living on my own, because I do want to be independent,” she said. “I do want to have my own space.”

Janice would like to buy a home one day in the distant future, when she has a family and needs more space to raise children. But even then, homeownership would be a nice thing to have, not a necessity. She says she isn’t opposed to living in an apartment. I feel the same. Unlike for past generations of twentysomethings, the idea of starting to save now for an eventual down payment on a home is just not a reality for me. And I’m okay with the fact that it may never be. You can live in an apartment, a co-op, or anywhere and make it feel like home.

Perhaps a more realistic question young Torontonians face than the prospect of homeownership is whether to stay in the city, or to build their futures elsewhere. Beyond the high cost of living, there are other factors some of my peers shared with me that make them want to leave. The rates of certain crimes in the city, like auto theft and assault, have increased over the past decade. And getting around can be brutal. According to the city’s Congestion Management Dashboard, a 2023 study ranked Toronto as the 17th most congested city in the world, with the average driver facing 63 hours of traffic delays a year.

Matt Vetcherebine, an English major student at the University of Toronto who is graduating next year, was born and raised in Toronto. He says that over the course of his university program, he’s grown to dislike the city more and more. In the past year, he says, his parents had their car stolen and there was a home invasion in his neighbourhood. He was also attacked on the TTC two years ago. The things he had always heard about in the news started creeping closer to him and those he loved.

Because of this, after he graduates, he wants to move away from the city, perhaps to somewhere in rural Ontario, or the suburbs of Montreal. He has a goal of becoming a fiction writer, whether for novels, video games, or TV—but he wants to pursue this dream in a place with a lower cost of living.

Those who told me they want to stay in Toronto, on the other hand, offered two main reasons. First, there is so much in the city, not only in terms of social activities but also in terms of diversity and culture.

Before moving to Toronto for university in 2023, Josephine, my fellow book club member, lived in Brantford, a city with a population of roughly 105,000 people. There, she says, it felt quiet and somewhat desolate. Her father immigrated from Trinidad, and she says the diversity of Toronto helps keep her in touch with her culture. And as a person of colour, she finds Toronto’s many ethnic enclaves, neighbourhoods, and festivals are a major incentive to stay.

“I feel like I’m not gonna find anywhere else [in Canada] throwing Caribbean parties like they do here,” she said.

She loves how she can decide to go to a concert last minute or how there are so many social events to attend. She even moved from Mississauga, where her campus is, to Cabbagetown in downtown Toronto, closer to the city buzz.

The second reason I heard for why people want to stay in Toronto after graduation is that most of their relationships are already here—whether with family, friends, or others.

“I was raised here, and I want to be of service to the community that raised me,” Ashvin Sharma, a 2022 graduate of McMaster University, told me.

Ashvin and I talked a lot about community and its importance in a city like Toronto, where as many as 37 percent of respondents in a 2023 report by the Toronto Foundation said they felt lonely three to four times a week. [The Toronto Foundation is one of the funders of The Local. This story was produced independently.] He says it’s not healthy for the city in the long-term if people keep leaving, and believes relationships can encourage more people to stay.

“I think people would grind their teeth and figure out a way to somehow pay bills and somehow get a job, somehow find a house, if they had a really strong community,” he said.

Community-building and relationships, Ashvin believes, are the key to helping us weather whatever crises come our way, whether it’s climate change, international conflicts, or any of the other big issues we face.

“I think what the world really needs is people to learn how to maintain harmonious relationships with each other and the natural world,” he said.

Ashvin previously thought he would be working in a high-paced environment after graduation, either in tech or international development. But instead, he moved back to Toronto to his parents’ home, where he hosts community events and has gotten to know his neighbours, all while freelancing for various tech companies. He told me he would have never thought his life would be like this while he was still in school. His idea of success now is based on the impact of his work and the ability to feel at ease, even though he acknowledged this may not be a popular view. I could see he actually cared about people and about the city.

“I really, truly, genuinely care about being of service to the collective well-being and harmony, and so all my decisions are aligned to that,” he said.

Ashvin said our interview gave him a chance to self-reflect, and I also did that a lot while hearing from my peers. Plans for the future, even the best laid ones, can change. I don’t know if my career will turn out the way I want it to, or if I’ll still be in this country after graduation. Looking back at my Post-it notes, I was trying so hard to convince myself that everything would be okay, but speaking with so many young Torontonians has shown me that being “okay” doesn’t necessarily mean that things will be easy. It means choosing to stay hopeful and building lives with meaning, despite whatever life throws at you.