The toads are back in the park, croaking a rhythmic soundtrack as Jim Aikenhead and Dan Schneider carefully hide a series of random objects in a forest clearing that’s just starting to bloom: a snakeskin, a small oblong skull, a bird nest.

On this warm, crisp May morning, the two outdoor educators are preparing for one of the first in-person classes they’ll be teaching at Mountsberg Conservation Area in Campbellville, Ontario, since the pandemic started. Soon, over 50 junior kindergarten students from Mississauga’s Cooksville Creek Public School will pour out of three yellow buses to find all these objects and more.

But a class here isn’t like a class in school, where teachers expect students to sit at a desk and pay attention. The program is called Nature Play and was designed and shaped by Aikenhead and Schneider, who each have 40 years of experience in outdoor education. The concept is simple: instead of a show-and-tell format, just bring children outside and let them explore and find stuff, giving them agency to lead their own education.

“Nothing they would want to do or talk about is wrong,” Aikenhead said. “The goal is to get to the site but we may never get there because the kids might be interested in everything along the way.”

Sure enough, it takes over 30 minutes for the class to make it to the clearing Schneider and Aikenhead prepared. Kids stop to pick dandelions, asking why they are different colours. They stop to watch geese waddling about and to listen to the toads. They stop to ogle at horses quietly grazing and to say hi to the many birds of prey being taken care of by the park’s animal rehabilitation program.

Nature is full of “good distractions,” Schneider said. “You just have to be outside to find them.”

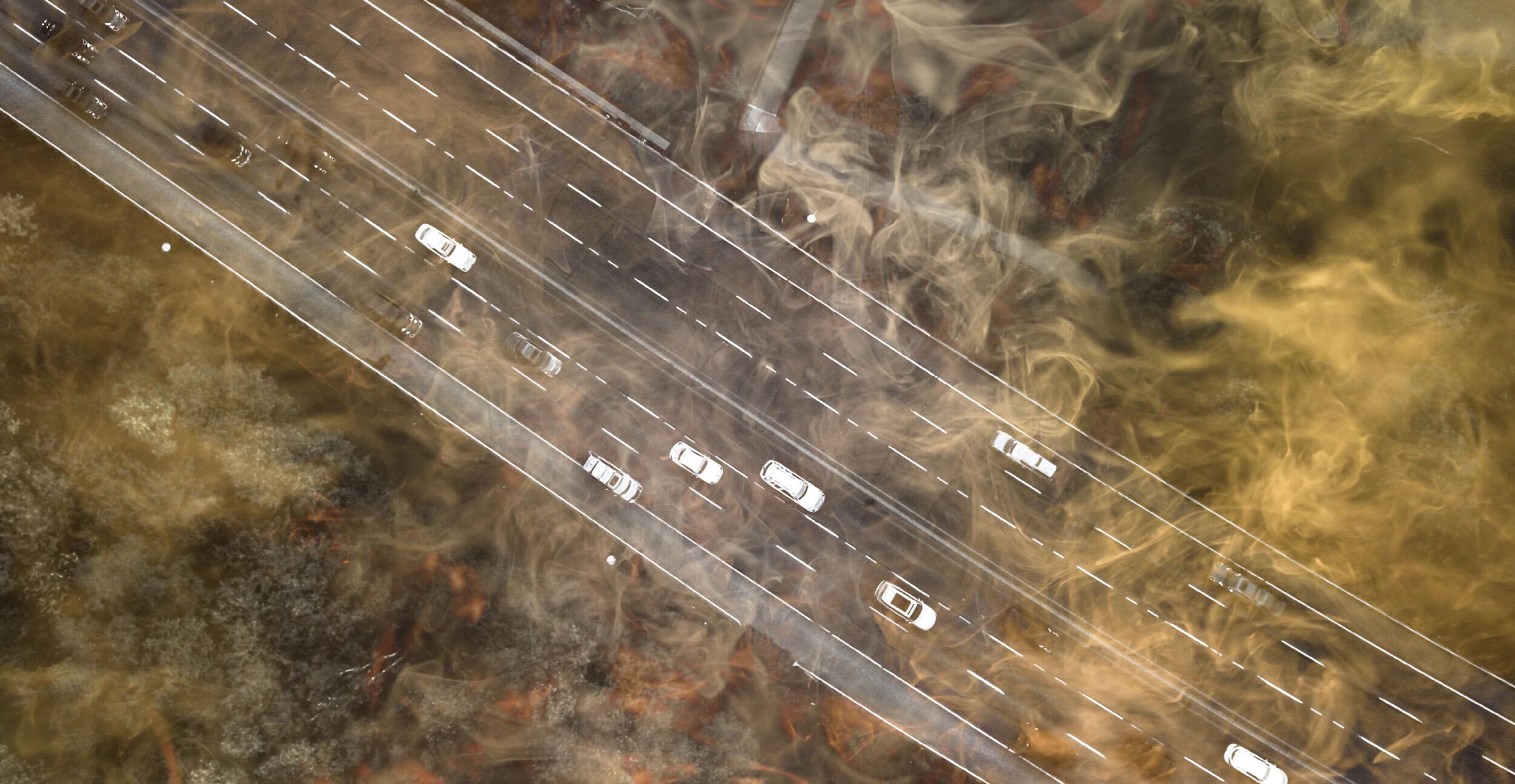

For Aikenhead and Schneider, outdoor education is a primitive activity for humankind—or at least it should be. At its core, it’s about exploring and understanding the natural world around us: the trees, the wildlife, the water, the sky. Doing so is essential for children to develop what these educators call “a climate consciousness”—an awareness, imagination, and appreciation of a world beyond concrete and four walls. But in the Greater Toronto Area, amid big city structures and the endless sprawl of overbuilt suburban life, outdoor education is often an inaccessible, structured, and expensive endeavour, especially for families from low income, racialized, and immigrant backgrounds.

This is for a multitude of reasons. The natural world isn’t always easy to get to: without a car, you need a strong appetite for long public transit rides to reach the few parks and wilderness spots on the outskirts of the city or beyond its boundaries in neighbouring regions. If children don’t get free access to these spaces regularly through school, their parents need a healthy bank balance to access camps or other outdoor programs.

These barriers of entry are a longstanding challenge for outdoor educators catering to a growing, increasingly diverse population in Canada’s largest urban areas. But one small silver lining to pandemic lockdowns is that the issue is finally being addressed head-on. When the world shut down, society went outside and rediscovered nature and the thrill of outdoor education. Now, educators and conservationists need to keep the public’s interest up as COVID restrictions slowly dissipate from daily life.

That means figuring out how to make nature and the great outdoors easier to access, less scary and, as weird as it sounds, more affordable.

“I guess we have to thank COVID for making people realize that when you get outside, you feel better,” said Schneider. He looks around the trees still blooming at the beginning of the summer season and exhales loudly as the air fills with a cacophony of chirps and croaks and children’s laughs. “We always knew but it’s become so much more obvious…It’s healthy for us to hear bird songs.”

Designing culturally relevant outdoor programs

Janelle Richards’s love for nature began in the forests where her father took her camping. She describes it as “a neutral base” to bond with her two siblings and to become one with the environment. It was also just a safe space to be a young Black woman growing up in Pickering, in the 1990s.

Her parents didn’t have a lot of money, so the only campsites she could visit were those that were heavily subsidized. In one, Richards had three Black counsellors, who taught her how to build fires and paddle a canoe, one of whom was an exchange student from Africa. Experiences like those would define her career moving forward: today, Richards is the only Black outdoor educator on her team at the Toronto Region Conservation Authority and vice president of the Ontario Society for Environmental Education.

Once, while teaching a kindergarten class, Richards had her hair in “two puffballs” on the top of her head. So did one of the Black girls in the class, who wouldn’t stop staring at Richards during the conversations and activities. Eventually, the girl turned to her: “Miss, you have hair like mine!”

The moment highlighted how rare it is for people like her to be in environmental education—which is important because people see the environment differently depending on who teaches them about it.

Having spent a lot of time speaking to people in the Greater Toronto Area about how they understand the natural world, Richards believes step one in reducing barriers to entry is to proactively ensure all communities are connected to nature in a way that’s “tangible and relatable.” Now, Richards chooses to integrate African imagery into her lessons: mangoes, okra, cotton. It grounds kids to their families, to their cultures and ties their daily lives to the environment in ways they’ll immediately understand, she said.

Hassaan Basit is the CEO of Conservation Halton, one of Ontario’s conservation authorities. The provincially regulated watershed protection agencies are mostly funded by municipalities and maintain some of their lands for public recreation. He also believes outdoor educators and experts need to hold the hands of various communities. Conservation Halton is working to do that through four new programs it launched over the past year.

The first was the Newcomer Youth Climate Forum, a series of workshops to teach new immigrants aged 15 to 20 about climate change in their communities. The youth study invasive species, collect native seeds, plant trees, and examine local environmental data. The program’s 35 slots filled up quickly.

Another saw Conservation Halton and the grassroots collective Halton Black Voices help those living in community housing beautify their neighbourhoods, while also taking Black families out camping and hiking. The program was designed for 40 participants—it ended up with 70.

The third program, Pride in Nature, was part party, part environmental education, an effort “to honour, commemorate and celebrate the local 2SLGBTQ+ community in Halton,” Basit said.

Last was introductory skiing, just for newcomers. One family had never seen snow before, Basit recalled, but there they were, two children and their parents swooshing down a hill within a few weeks of landing in the country.

“It all proved that we need to reach out and attract people, and engage them to let them know nature is something they can all be a part of,” Basit said.

There are many tangible ways to make outdoor education accessible to all communities, Richards said. “A really good way to start is by building connections,” she said. That includes nature-based storytelling in different languages, and visiting parent-teacher councils and neighbourhood groups to understand how people connect with the environment, or want to. It means understanding that overnight camps may not be a thing some parents are accepting of, culturally. Reframing the idea of the environment to include backyards, schoolyards, and small, local parks is a much easier first step.

“If we want people to care about climate change, if we want people to engage in stewardship, if you want people to be the next thought leaders on how to tackle environmental problems … and reduce their own carbon footprint, then we have to let nature do the teaching,” Basit said. “But in order to do that, we have to learn how to make nature accessible.”

Schneider and Aikenhead have spent the bulk of their careers trying to create an outdoor curriculum that does exactly this: make space for students to dictate their learning from what they know and what they’re curious about, as opposed to dictating things to them. The core reason is that many kids may be seeing some things for the very first time.

“I’ve seen kids that are terrified of putting their hand in a pond,” Aikenhead said. “It dawned on me that they may have come from a part of the world where you can’t do that. So our job is to help kids get beyond that fear and explore things they might not have found engaging before.”

As Aikenhead leads the group down the parking lot, past the lake, through the woods and into the clearing, he reminds them to use all their senses, to tell him whatever they see, feel, smell, touch, taste. Some hesitate, so he encourages them to try touching a flower by doing it with them.

One kid finds a moth cocoon under a log and says “ew” until Aikenhead explains “how cool” the discovery is. Another starts banging on a log with two tree branches like a drum; Aikenhead joins him, creating a rhythmic echo throughout the clearing.

“Look what I found, look what I found,” a little girl shrieks, running to Schneider with cupped palms. A tiny brown worm is crawling along the lines of her tiny hands. “I found a worm! I found a worm!” Schneider helps her put it back under the log where it came from so “he doesn’t feel lost.”

“See? Nature creates its own lesson plan,” Schneider said with a grin.

The great — but costly — outdoors

Outdoor educators in big urban centres like the Greater Toronto Area have one big challenge: once you get kids and their families to fall in love with nature, how do you keep them there? Camping requires money, for equipment—think tents, camp stoves, flashlights and more—and entry. So do most outdoor excursions and summer camps.

So after instilling that love, step two is figuring out stable funding for outdoor education programs so that everyone, regardless of their income, can easily access them.

Conservation Halton’s four new programs found funding thanks to the efforts of its linked foundation. It’s unwieldy to manage, as it comes from all sorts of streams.

Last year, Cogeco gave $10,000 for the program with Halton Black Voices; this year, the company along with Hydro One and others have collectively given $55,000. RBC Foundation chipped in $100,000 for the youth climate forum, with in-kind support from the outdoor clothing brand Keen; this year, the program will run with $25,000 from the Catherine Donnelly Foundation. Canadian Tire, ScotiaRise and Minto Communities gave $58,300 in money and gear to get the skiing program started. Another Conservation Halton program that teaches middle school students environmental stewardship at greenspaces near their schools got $62,550 from TC Energy and SC Johnson.

“This type of funding is not sustainable,” Basit said. Aside from the effort required to court and secure funders, such donations mean programming is often bound by corporate priorities: promotion, reach, publicity. And not all of the programs had their funding renewed. To continue with those, Conservation Halton would have to use excess revenue from park entry fees, which is how it pays for 30 percent of its existing programming.

Halton charges an entry fee between $6 and $10 for its parks, but conservation authorities have never been allowed to charge participants for active outdoor education and Basit doesn’t want to, anyway. For a long time, they couldn’t charge municipalities either, but new updates to conservation authority regulations now make that an option.

“There’s no baseline funding from the public sector for outdoor education,” Basit said. “It really should be from the government.” Some 75,000 children visit Halton parks every year, which means Conservation Halton needs at least $150,000 to create amazing programming that “takes away the unfamiliarity, the threatening element of ‘what do I need?’ and ‘how do I get there?’” Some of the sheer team effort needed to set up these programs goes unpaid.

Basit believes stable core government funding would provide a foundation for extra, targeted programs.

The right way to get those donations, Basit said, is to first get community feedback on what programs people want and what barriers they’re experiencing. Only then is it time to create programs and find funding for them—which isn’t actually that hard, when the community is interested.

“It’s a lot easier to get funding today than it was 10 or 15 years ago because there’s a level of consciousness around these issues right now,” Basit added. “It’s not hard to make a case for underrepresented communities in nature-based programs.”

But on a grand scale, affordability is a much harder problem to fix. And not all organizations seem to want to. The Narwhal reached out to dozens of outdoor summer camps in Ontario where fees range from $30/day to $1,500-plus/week—and even being able to pay doesn’t guarantee successful registration, which can require filling out multiple forms and navigating competitive online sign-ups as early as the fall before the program happens.

Longstanding institutions, such as Camp Muskoka and Camp Tamakwa—where some campers’ families pay $11,000 for them to spend the whole summer canoeing, sailing, and fishing—didn’t respond to multiple requests. In the end, only two shared their approaches to attempting financial and cultural equity for participants.

One was the Pine Project, a $415/week summer day camp program in Toronto. Executive Director Andrew McMartin was born and raised in a city environment, and said connecting with nature was always a special experience for him, one he wanted to translate to others.

McMartin wanted his program to be geographically accessible, reachable by anyone in Toronto. “We want to meet people where they are,” he said. “I feel like the city and urban, modern, Western life does a really good job at disconnecting us from a more consistent relationship with nature.”

The Pine Project team spent a lot of time negotiating with the City of Toronto for access to city parks, and in the end, Martin only got permission to set up in the west and east end, not in North York along the Yonge subway line. Making the Pine Project accessible to all by public transit remains a barrier.

Martin also created the Pine Project as a non-profit, so he could raise funds for a bursary program. This, too, remains a work in progress. Subsidized slots get filled up fast, so McMartin is trying to figure out how to fundraise and create more capacity, especially as the pandemic has increased demand.

The other program that shared its approach was Evergreen Brickworks, located in Toronto’s Don Valley, which offers $405/week summer camps that fill up the day registration opens every January. Senior program manager Heidi Campbell said the camp tries to cover 25 to 95 per cent of student costs through bursary programs, and the goal is that 10 percent of registered campers receive these bursaries.

Brickworks reserves a couple of spots in each of its groups as “bursary spots” to ensure they remain available even after registration day. Interested parents have to fill out a detailed application form and then wait to see if their chosen dates have slots available. “Most of the campers and families who apply for the bursary receive the support requested,” Ethan Rotberg, a spokesperson for Brickworks, said in an email. “We only stop accepting bursary applicants once we are fully booked or we have maxed out our funding.”

Brickworks is trying to reduce these barriers through other means too, Campbell said, like offering shuttle service from Broadview subway station. Campbell said the organization is always creating partnerships with corporations and other funders to offer more free outdoor programming. It’s also currently partnering with school boards to create more outdoor classrooms, planting hundreds of trees with support from federal grants.

McMartin and Campbell both say another challenge is attracting campers that represent the diversity of Toronto. While the makeup of Pine Project’s board and staff have become more diverse since the program started, the participants have not. To McMartin, that means there’s more work to do in terms of outreach.

“If I’m being transparent, we need to do a lot more work to get a well-represented community of folks to participate in our programs from all sensitive backgrounds and communities,” he said. “To do that, we all need to first learn that there’s no one way or right way to engage with nature, and we need to integrate that in our programming to reduce barriers.”

Integrating outdoor education into the entire curriculum

A longtime outdoor education teacher, David Hawker-Budlovsky is now principal for outdoor education at the Toronto District School Board, Canada’s largest with almost 250,000 students. He said the goal has always been to give universal access to every student to at least two day trips and one overnight experience in their nine-year elementary school career.

Officially, every elementary school has access to the board’s nine outdoor education centres. But in reality, there aren’t enough time slots for every class at every school. Teachers look to conservation authorities and camps for other options, but these come at a cost. Brickworks’ school program is $30 a day, per student. Mountsberg is cheaper at $6.75 a child but that doesn’t include the cost of the 40-minute bus ride to the park.

Two years ago, the school board doubled fees for a three-day overnight camp excursion for the first time since 2002, in large part because everything from gas prices to equipment costs had increased. These fees are set on a sliding scale, from $50 to $150. A few seats in each outdoor school program are allocated especially for low income and racialized students. But to snag one, teachers or parents must confirm the child is in the top 300 on the Toronto School District School Board’s Learning Opportunities Index, which measures the challenges affecting a student’s success, and provide proof that demonstrates their need.

It’s up to each school whether they charge students directly or not, Hawker-Budlovsky explained. Some do, but others try to make it free by working outdoor education into their budgets, getting classes involved in fundraising or enlisting parent councils for help. If a student can’t pay, the fee should be waived, Hawker-Budlovsky said, but that’s up to each school’s discretion. If he hears about someone having difficulty, he steps in to find solutions.

The board is trying to be more intentional about integrating outdoor education into its curriculum, and into every school and class. Two years of at-home learning during the pandemic gave the board time to review their outdoor education practices. What they found, Hawker-Budlovsky said, was chaos: each school and each grade was assigned a limited list of different parks they could access, seemingly at random.

Now, schools choose the outdoor program and location most suitable for their kids. For example, a school in Scarborough might find going to Toronto Islands more enticing for its class than a two-hour trek to a camp in Muskoka. “Schools know their families best,” Hawker-Budlovsky said. “They know what will encourage their kids to enjoy the outdoors.”

The goal is to make the outdoors “an entry point” for the rest of a kid’s education. That means showing students they can find angles in nature for math. Get them to write about all the things they observe outside. Learn art through street paintings. Participate in a community garden. Make forts in the backyard, if they have one.

Rachel Irwin, an outdoor educator with the Halton District School Board, also wants to break the privilege that is associated with the outdoors. During one night hike, Irwin told her students to lie down and look at the stars. One said afterwards that they had never seen stars before at all. “That’s when I realized how disconnected kids in cities could be from the environment,” she said, “and how much we needed to help them enter it.”

Irwin runs a new experiential learning initiative called Nature’s Neighbourhood Eco Action Ranger or Nature’s NEAR, which takes students on neighbourhood walks to immerse them in the pockets of nature closest to them. Irwin hopes she can expand the program to newcomer adults who come to the school to take English classes, because if they fall in love with nature they’ll pass that appreciation down to their kids. “They’ve never canoed or camped so having an invitation to try these things at minimal cost and with help is a big first step,” Irwin said. “It also starts with baby steps. Instead of skiing down a hill, let’s just become comfortable feeling the snow across our bodies.”

“What you need to consider is ‘does the school have a door?’ Because if there’s a door the students are able to go outside and interact with their environment. And that may be to a stream, a pond or ravine or a forest, or it may be a laneway with amazing street art or it may be a community walk looking at patterns and numbers and shapes outside your door,” said Hawker-Budlovsky.

“It’s learning that sticks,” he added. “It’s learning that stays with them.”

But it’s also learning that still can’t be accessed by everyone. In 2019 Ophea, a charity that supports physical and health education, released a study of 232 schools of Ontario’s 5,000 schools that found that a third of schoolyards are fully paved. Another 13 percent had no trees. Only 37 percent of the schools surveyed had outdoor classrooms.

Even boards that do value outdoor education can be stymied by a lack of funds from the provincial ministry of education. Basit would love to see governments subsidize conservation authority programs for school boards. He also wants boards to have more funding for outdoor education centres, which are often the first to be slashed in the event of budget cuts. “The more urbanized schools get, the more funding school boards should receive to take them into nature,” he said.

Richards would also like to see more subsidies or at least a sliding scale structure, as well as a support system that prioritizes low income communities in these programs—like help for parents to navigate registration and bursary paperwork. “I know camps need money to operate but being lenient and understanding would go a long way in making nature more accessible,” she said. “We just need camps to put in the effort.”

Over at the Mountsberg Conservation Area, the issue of finances is one Aikenhead and Schneider struggle with constantly.

“One side of my brain says all of this,” Schneider gestures to the trees and water and birds around him, “should be free. But we maintain all this at a cost.”

“We try to keep fees as low as possible,” Aikenhead said. “If there are more kids attending that helps. But ideally if there were a million of these centres, there may be no cost.”

“The main problem is that nature and the whole outdoor education ‘industry,’ if you want to call it that, isn’t essential yet?” Aikenhead added. “Because if it was, it would be financially supported.”

Mountsberg isn’t just a classroom. It’s also a space to nurse birds back to health, a space to preserve natural history, a space to host family and community events. That’s why Aikenhead, who technically retired before the pandemic began, couldn’t stay away for too long.

“You never get to see some things this close without outdoor education,” Schneider says, as he stops the class to say hello to Cornelius, a 26-year-old one-winged bald eagle who can no longer fly. Cornelius is a “creature teacher” now, evident by the swarm of kids standing in front of him hoping he’ll squawk something.

He does as the class starts to walk away. “Don’t worry,” Schneider says to the majestic, still bird. “We won’t forget to teach them your story too.”