Amina couldn’t avoid him. The student who she says had sexually assaulted her was all over campus.

In February 2023, during her third year at the University of Toronto, Amina (who has been given a pseudonym out of concerns for her privacy and safety) had gone to a house party in downtown Toronto. She had been with friends, and wasn’t expecting anything except a typical night out. But she says she blacked out at the party, and woke up in the host’s apartment the next day disoriented, in pain, with bruises on her back and head.

She learned from friends what had happened: they had found Amina in the bathroom with a male student. They told her they saw her giving him oral sex, and could tell she was clearly unable to consent. In a report issued by U of T, which The Local has seen, an independent investigator found that Amina “was significantly impaired at that time (unable to stand or walk on her own, being held up by others, slurred speech),” and “was not in condition to provide consent to sexual acts.” The report stated that a witness corroborated the allegation, and that two others provided “indirect evidence.” (The report does not elaborate.)

“I don’t really have much memory of what happened in the bathroom,” she said. Her friends described kicking the man out of the apartment.

Amina reported the alleged rape to the Toronto police and notified the University of Toronto’s Sexual Violence Prevention and Support Centre (SVPSC) that same month. At the time, she hadn’t wanted the university to make any inquiries into the incident because she believed the police would take care of it. But she says the police didn’t want to pursue the case and refused to press charges, despite witness statements supporting her account. (Toronto Police Services told The Local they could not confirm any details as they do not discuss victim identities.)

In the year that followed, her academic life suffered. She dropped classes, and says she didn’t feel safe on campus, fearing how many people might know what had happened.

In February 2024, Amina escalated her complaint with the university, requesting an investigation into the alleged attack. She was looking for clarity, and to some degree, to know whether the university could mete out consequences given the police hadn’t. But “it was also mainly just about getting closure,” she said.

Join the thousands of Torontonians who've signed up for our free newsletter and get award-winning local journalism delivered to your inbox.

"*" indicates required fields

All complaints about sexual violence within the U of T community go through the SVPSC, and are reviewed by the Office of Safety and High Risk to determine whether they fall within the university’s jurisdiction. During the assessment, the university can choose to implement interim measures to ensure the safety or well-being of the complainant, like no-contact orders or mental health supports.

It took four months for the university to inform Amina that it would formally investigate her complaint, and place interim conditions on the alleged perpetrator. Those conditions included a no-contact order, a requirement that he leave any shared space on campus if he sees her, and cooperation with the university to avoid being enrolled in the same classes.

Late in the fall 2024 semester, Amina says he defied those instructions. It was some relief that they didn’t share any classes, but when she encountered him on campus, she says he wouldn’t leave like he had been instructed to. After the first incident, Amina contacted SVPSC.

She was told by staff at the SVPSC that campus security would be available anytime if she encountered her alleged attacker, and that they would “want to know of any breaches.” But when Amina contacted campus security, she says they’d never heard of these conditions, or of her.

“They asked me to explain the entire process of why I needed to report to them in the first place, and why it was relevant to them, and why they need to do anything,” she said.

In a discussion she says took more than an hour, she had to recount the details of her alleged rape. They seemed, in her assessment, to feel no obligation to keep her safe.

“It just made me angry, because I thought the conditions would at least be helpful in making me feel safe again, but he didn’t follow them. And there weren’t many consequences for him not following the conditions.”

Throughout the process of dealing with the SVPSC, from initial complaint through to investigation, Amina describes being put through a long, retraumatizing ordeal in which she had to recount what she’d experienced multiple times, in paperwork and in interviews, with little support from the Centre. In a statement to The Local, U of T said people who report allegations of sexual violence “are not asked to repeat their accounts more than is necessary for the implementation of the policy.”

As Amina struggled in class, she says she found it was easier to get accommodations and extensions for assignments due to her ADHD diagnosis, rather than due to her being a sexual violence survivor. The SVPSC itself cannot provide academic accommodations, only advocate for the requests, which then fall to the purview of the school’s academic departments.

University policy requires that each step of the reporting and investigation process “be completed as expeditiously as practicable.” Despite this, as of October 2025, it’s been over a year and a half since Amina first reported being raped to the SVPSC, and her case hasn’t yet been resolved. The independent investigator’s report found in January of this year that her account had been “partially substantiated,” with interviews from Amina, the accused, and witnesses. The accused provided a “limited response,” the report said, including “a general statement that none of his actions were in violation of the student Code of Conduct on the day in question.” The school told Amina this May that it is planning to have a hearing “to determine whether or not Sexual Violence (as defined in the Policy) occurred and, if so, the appropriate penalty or remedies.” Though she has heard from the Centre since, she says a hearing has still not been scheduled. U of T told The Local they cannot comment on specific cases, but that they are “committed to moving cases forward in a timely manner.”

Amina’s experience with the University of Toronto’s response to her sexual assault is part of a broader pattern. In the years after the Me Too movement, it seemed like there was finally an open forum to have urgent, bracing discussions on the prevalence of sexual violence on post-secondary campuses. The movement galvanized and influenced policy changes in Canada. But all that momentum has evaporated. The pandemic paralyzed student organizing on university campuses for years. Misogynistic backlash to changing social norms has led to a backslide in the conversation about women’s safety and rights. In this climate, universities faced with increasing austerity have made sexual violence prevention and response less of a priority. Today, survivors say getting help from their postsecondary institution remains difficult, confusing, and ultimately inadequate in keeping students safe.

In March 2016, Ontario passed new legislation mandating that all post-secondary schools implement policies addressing sexual violence on campus, and set out a process on how the college or university will respond to and address incidents. The Sexual Violence and Harassment Action Plan Act was passed in the wake of the high-profile sexual assault trial of CBC broadcaster Jian Ghomeshi, which prompted a national conversation around sexual violence, and a subsequent swell of campus organizing and reports about sexual violence at post-secondary institutions. (Ghomeshi was acquitted of all charges.)

Then in 2018, the year after the peak of the Me Too movement, the Council of Ontario Universities conducted the first and only comprehensive survey of all Ontario schools on the issue of sexual violence. It found that nearly a quarter of the more than 117,000 post-secondary students who responded said they had experienced a sexual assault in the 2017-2018 school year.

The provincial sexual violence act required schools to complete a review of their policies every three years.

Dawn Moore, a law professor at Carleton University, warned in 2016 that it would be difficult to measure how effective any of these policies are, given that survivors rarely report sexual violence and “institutions do not want to receive reports.”

The actual state of affairs of how prevalent sexual violence is—especially on very large university campuses—is obfuscated by the schools themselves, said D. Scharie Tavcer, an associate professor of economics, justice, and policy studies at Mount Royal University in Calgary, and the co-author of a 2023 book on sexual violence policies at Canadian schools.

Post-secondary schools are very reluctant to collect and provide any of their own data on sexual violence or how many students have come forward, she said.

“Universities, in my opinion, operate from a liability perspective,” said Tavcer. “They operate from ‘what harm will this do to the university as an entity, in terms of its reputation, in terms of liability, legal liability, insurance liability’—so they operate from that kind of fear perspective,” she said.

There has been no assessment of whether the mandatory sexual violence policies have actually made schools safer than prior to the law coming into force.

“We never really know the extent to which those policies are actually implemented well,” says Lise Gotell, a University of Alberta professor specializing in feminism, law, and sexual assault. “These processes are really shrouded in secrecy.”

StatCan research from 2020 found that students who reported sexual violence incidents to their school were three times more likely to disapprove of their institution’s approach to sexual violence prevention than non-survivor students.

When Amina was reporting her allegation of rape to the SVPSC, she turned to a student-run organization for the emotional support she says she wasn’t getting from the Centre: The PEARS Project, which stands for Prevention, Empowerment, Advocacy, Response, for Survivors. (She has since taken on volunteer roles working with the organization.)

Micah Kalisch founded PEARS when she was in her second year of university in 2020. She is now finishing her master’s degree in women and gender studies at U of T, and PEARS has 10 branches across the University of Toronto community, including at the Scarborough campus.

The main issue Kalisch sees often, after helping dozens of students report an incident to the SVPSC over the past few years, is the lack of clarity on the sexual violence reporting and investigation process, which leaves survivors in the dark about what to expect when they turn to the university.

The SVPSC is a fairly new university body, only opening in 2017. On its website, the Centre outlines its commitments: emotional support, connecting to counselling services, advocacy for university accommodations, safety planning supported by campus police, and ultimately, a promise to believe the person reporting.

Students coming to the Centre with experiences of sexual violence have the option of “disclosing,” which would prompt the school to implement accommodations and supports—but nothing further. The other option is to “report,” which involves an investigation and can lead to disciplinary action against the accused.

Survivors are assured they will direct the conversation and they can drop in and out of the process anytime.

“A core tenet of being trauma informed and survivor centric is making sure that survivors have that autonomy and that choice and control, and they know what they’re getting into when they go through these processes,” says Kalisch.

But in her experience working with students, she says that’s not what happens. Kalisch describes the process as opaque, confusing and emotionally trying for survivors, with disparate and arbitrary outcomes.“As somebody who’s gone through it with a lot of people at this point, I still don’t really understand it, because it seems so different for everyone,” she said.

“We’ve seen everything from survivors being told that they’re liars, that it didn’t happen,” she says. Some survivors feel the process of the SVPSC re-writing their accounts of sexual violence in formal language—one of the steps in the reporting process—also erases nuance from the encounters, including aspects of racism, ableism, or other kinds of oppression that can often show up in incidents of sexual violence. StatCan found in the 2020 study that students with disabilities, or some students from marginalized communities, including bisexual people and Indigenous men, faced disproportionately high rates of sexual violence.

Kalisch also says she’s seen students pushed to sign non-disclosure agreements, though U of T denies using them. And most importantly, many students are not getting swift accommodations or safety planning when they need it.

“It’s different for everyone, but it tends to be a pretty upsetting process,” she said.

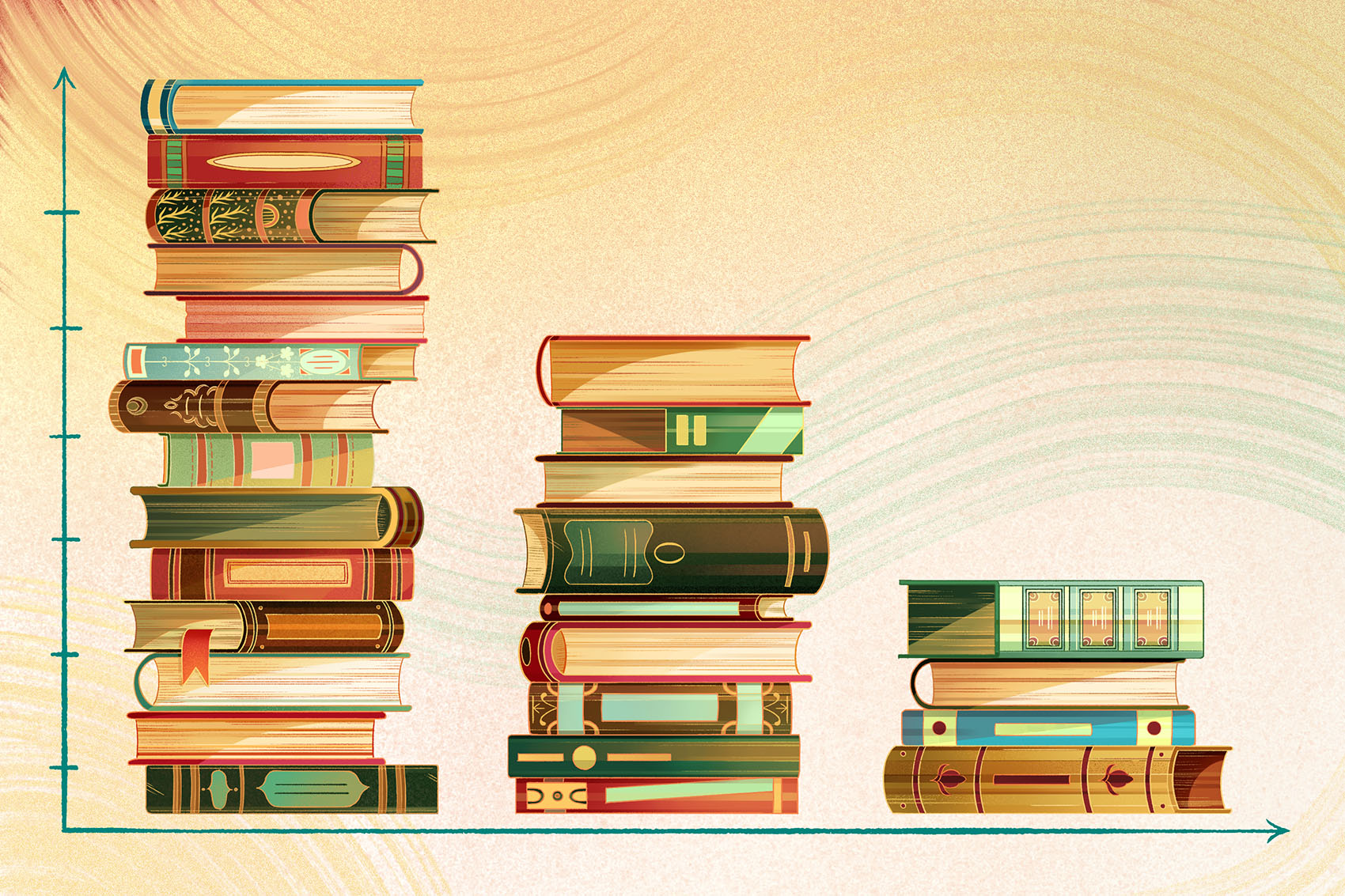

In annual reports, U of T lists how many complaints of sexual violence are made to the university each academic year, their outcomes, and how long the process took. In the 2024-25 school year, there were 208 disclosures of sexual violence to the university; in 50 of these cases, the complainant requested an investigation. In both that year and 2023-24, U of T reported that the majority of cases took more than 12 months to conclude. The hearing process, which Amina is currently undergoing and which is used in very few cases—just three in the 2024-25 school year—takes an average of 23 months.

In its statement, U of T said, “In response to feedback in the 2022 policy review, the University hired two more case managers, and during 2024-25 resolved more than twice as many cases than in the previous cycle.”

Lila, a U of T student who finished her undergraduate studies in June, says help from the SVPSC came far too late to help her feel safer on campus, after almost a year of alleged sexual harassment by a fellow student. (Lila is using a pseudonym to preserve her safety and privacy.)

When Lila filed a report with the SVPSC, she said it took six weeks for temporary measures to be placed on the student to keep his distance from her, while a formal investigation began. By the time the measures were in place, it was winter break and Lila had missed most of the semester’s lectures to avoid her alleged harasser, with whom she shared classes.

Lila describes the reporting and formal investigation process as cold, imitating the language and processes of the legal system, with paperwork and interviews and having to repeatedly tell her story, as Amina had. Reporting an incident meant the accused would be notified of all the allegations and learn who is making the complaint. “I was really scared of him retaliating in some way, or just running into him,” Lila says.

In a statement to The Local, U of T said, “In alignment with the principles of procedural fairness, the University is required to share with the Respondent the specific allegations that will be investigated.”

While waiting for the university to conduct its investigation, Lila says she found out from classmates that she was not the only woman this man had allegedly harassed. It reassured her she’d done the right thing in reporting him. But it was immensely difficult.

Lila says that by the time the investigation was completed at the end of April, she was about to graduate. Her entire fourth year had been irretrievably altered. And the way the university conducts its investigations, she said, places an arduous burden on people who’ve experienced gendered or sexual violence. (The Local has seen a copy of Lila’s complaint and the letter from the respondent, who denies any wrongdoing, but we have not seen the university’s final investigation results.)

This year, U of T is conducting a review of its sexual violence policies, as mandated every three years by the provincial Action Plan.

Kalisch does not believe U of T’s policy review will make any substantive improvements to how the school currently handles sexual violence on campus.

“The bottom line is always going to be liability and press and what’s going to look good for them and how to make problems go away,” she said.

Gotell adds that while policy reviews are important, they often aren’t detailed enough to get a true understanding of whether the policies are actually working. She describes the policies as “performative”: “the institution updates its policy, there’s a lot of fanfare around it, but then we never really know the extent to which those policies are actually implemented well.”

But Kalisch also knows that even a perfect policy doesn’t necessarily translate into real change for students. She says there are aspects of the school’s policy which work, in theory—like restorative justice options and connecting survivors to outside organizations.

“On paper, this sounds good and important. But these are things that we’re not seeing happen in practice,” she says. “If there are no accountability measures to ensure that they’re adhering to it, it doesn’t mean anything.”

In its statement, U of T described being “truly grateful to all who engage with the review processes and advocate for changes to improve the policy for our entire community.”

In 2022, PEARS, along with other campus organizations including the University of Toronto Students’ Union, collected experiences of students who reported to the SVPSC and presented them in a video called “Surviving the Centre.”

In the video, students read out accounts submitted by their peers. One student describes feeling “surprised” during the reporting process and that the Centre only gave a “general” overview of what to expect. Others describe calling for help and being sent straight to voicemail, or having to repeat their story several times when they did not think it was necessary. Many include comments about the Centre being too slow to take action. “It ends up being too late by the time you hear from them,” one account reads.

Feeling little relief from her experiences with the SVPSC, Lila says what she wants to see is a mandatory course on consent for all post-secondary students.

Students moving into residence at U of T are required to complete an online module about consent, which the school launched in fall 2023. According to the school, the module covers consent in relationships, setting boundaries, what sexual violence is and how it might occur, and resources on and off campus for survivors.

The SVPSC also has frosh week programming on consent, though none of it is mandatory. For many students who have come to campus this fall, the short interactions with the school’s SVPSC or with the PEARS team at the frosh week clubs fair may be the only campus-facilitated discussion on sexual assault or consent that they encounter.

Experts and advocates The Local spoke with say schools seem increasingly concerned about saving money, and reluctant to devote resources to sexual violence response, especially at Ontario universities, which receive the lowest level of public funding of any Canadian province. Provincial support was already low pre-pandemic, and has only decreased since.

Without adequate funds, says Charlene Senn, a professor and social psychologist at the University of Windsor, “you do not have time in your position to actually develop comprehensive sexual violence prevention, because you are needed on response, and that’s the more immediate thing…and then the cuts happen.”

The more cuts, she said, “the more universities are going to have to cut off everything that isn’t the basic running of the university.” Sexual violence prevention and response fall to the bottom of a long list of more urgent concerns.

This “backsliding” eight years on from the Me Too movement is also fuelled in part by a growing conservatism on campuses among both administrators and students, says Cyrielle Ngeleka, chairperson of the Canadian Federation of Students-Ontario. This environment, bolstered by policy that cracks down on diversity and inclusion efforts, stifles critical discussions on gender, sexuality, and how gender-based violence is a symptom of patriarchy.

“We’ve already identified there’s been a shift to the right among institutions and unfortunately, among some students overall,” she said.

Humberto Carolo is the head of White Ribbon, a Toronto-based non-profit that works to end gender-based violence in Canada and globally. It was created in 1991 as a response to the 1989 École Polytechnique massacre, in which the gunman shouted “I hate feminists” before killing 14 women in an engineering class.

“The attitudes, the beliefs, the hatred that led to that violence 35 years ago is still very much alive today.” Carolo said.

The misogynistic views harboured and perpetuated by the manosphere, channeled through social media and podcasts geared towards men, are entering young boys’ minds as “fact,” Carolo says. First-year undergrads are coming to school, he adds, with fundamental beliefs about women, “that blame women and the women’s movement…for the challenges that young men are experiencing in today’s society,” Carolo says. These, in turn, fuel sexual violence.

White Ribbon runs workshops directed toward university- and school-aged men and boys that examine why men’s violence towards women remains so pervasive and insidious in Canadian society.

But despite the urgency of the moment, Carolo says, funding cuts can mean less money spent on programs like the ones run by White Ribbon.

“The cutbacks to resources and programming in universities and colleges [are] having an impact,” he said.

Amina is now in her fifth and final year of her undergraduate degree. She says the emotional toll of her ordeal led to her drop many classes, which cost her more time and money to finish her degree.

As far as Amina knows, the man who allegedly assaulted her is still a student. Critics say that in cases like these, if either the alleged survivor or perpetrator graduates, the case is dropped by U of T—but the university says if a student leaves, the school “may still choose to proceed with an investigation.”

Though she feels more at ease than she has in the past two years—she’s in therapy to process what she’s experienced, and to cope with her anxiety and fear—Amina says it’s hard to succeed in school when simply being on campus feels isolating.

“It feels really hard for me to focus in classes…and to pass courses in that kind of environment,” she said. “The university doesn’t actually take any actions to make [students] feel safer.”

Even though a third-party investigator found in January 2025 that Amina’s allegation could be “partially substantiated,” meaning the investigator mostly believed her, Amina says a hearing to actually determine what the next steps are has not been scheduled yet.

She still wants to see her alleged attacker removed from U of T. “He doesn’t see what he did as wrong.” she says.

At this point, Amina would also like to get on with her life. The avenues she pursued to report this student for criminal activity—police, the school—haven’t yet resulted in any changes.

“I don’t really try to think about stuff like that anymore. For the year after it happened, I spent a lot of time trying to remember what actually happened,” she said. “It just wasn’t actually helping me in any way, helping me progress as a person. It was just making me feel a lot of pain.”

As the semester continues, Amina is focusing on staying on top of mounting assignments.

“At this point, I’m just glad I’m almost done at U of T, and I can move on.” she said.

Correction—Nov. 13, 2025: a previous version of this article incorrectly stated that the University of Toronto Office of Safety and High Risk plays a role in coordinating academic accommodations. In fact, decisions about accommodations fall to the school’s academic divisions.