In October 2019—a week after climate strikes shut down cities across the globe, 12 months after the UN climate panel delivered an unprecedented report urging world leaders to act now to avoid catastrophe, and just three decades after the first international attempts to halt climate change—Toronto’s city councillors unanimously voted to declare a “climate emergency.”

The declaration was for the purpose of “naming, framing, and deepening our commitment to protecting our economy, our ecosystems and our community from climate change,” and it was hard to argue with the sentiment. The most cursory reading of the UN climate report, or even just a selection of local weather forecasts, makes the emergency plain. And Toronto’s role in it is undeniable. Canada is among the world’s largest greenhouse gas emitters per capita, and Toronto, by virtue of being the country’s biggest city, has an outsized role in those emissions. According to the Toronto Atmospheric Fund, 44 percent of Ontario’s total carbon emissions are emitted from the greater Toronto and Hamilton area. Any conceivable path to a Canadian low-carbon future goes straight through the GTA.

The emergency declaration followed the city’s adoption of TransformTO in 2017, a plan to reduce greenhouse gas emissions by 80 percent against 1990 levels by the year 2050 (a target date that has since been brought up a decade to 2040). But the urgency implied by the word “emergency” has not always been felt at the policy level. A climate emergency is not the time to invest billions of dollars in rebuilding an aging expressway. It is not the time to squash a storm water fee that would incentivize landowners to reduce their hard surface area. And, at the provincial level, it is definitely not time to cancel renewable energy projects—a move that will increase greenhouse gas emissions 400 percent over the next two decades.

For the people that live here, regardless of whether we collectively hit these targets, the focus will be on adaptation. Even if we’re successful at limiting the global temperature increase to 1.5 degrees Celsius above pre-industrial levels—as called for in the Paris Agreement, and above which serious, irreversible damage to the earth occurs—cities like Toronto are already well on their way to becoming less habitable. The planet is already 1.1 degrees Celsius warmer than it was in the late 1800s.

And while climate change is a global phenomenon, it has hyper-local consequences. History has shown that harms from extreme weather events will always disproportionately affect those already on the margins of our city—the elderly and the urban poor, those who live or work in buildings without proper ventilation or cooling. Climate change is the result of meteorological conditions, sure, but our experience of it is the result of specific policies and politics—the way our cities are organized, the inequities already baked in.

In our new series, “Toronto’s Climate Right Now,” we dig into climate vulnerability and adaptation in Canada’s biggest city. The project is a collaboration with our friends at The Narwhal, a publication that covers climate and the natural world better than anyone in the country.

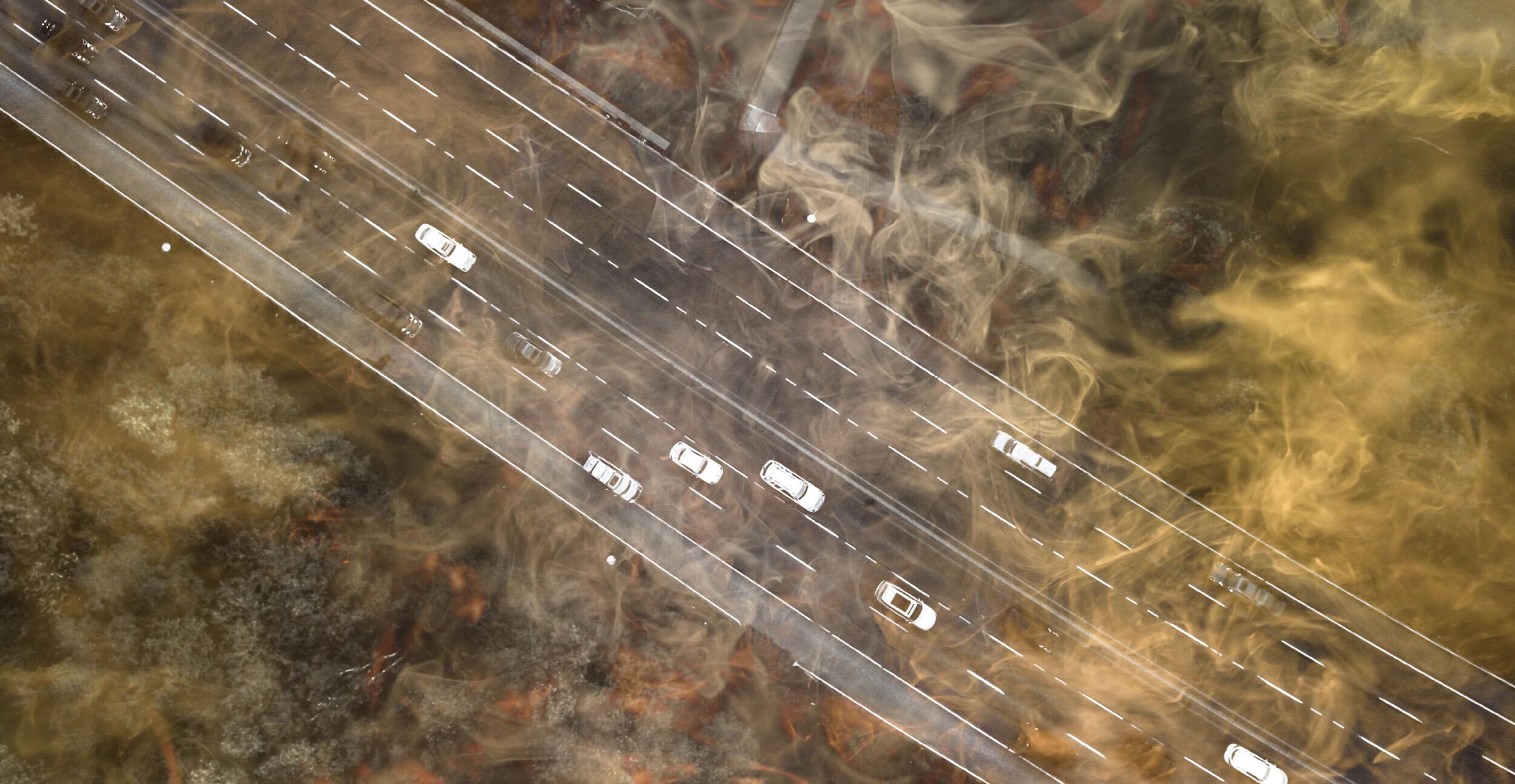

Over the next two weeks The Narwhal and The Local will co-publish stories from the frontlines of Toronto’s climate crisis—from an in-depth feature on heat inequality, to a story about our shifting ideas of what makes an “invasive” species, to an investigation into how different neighbourhoods experience car pollution.

The pieces are critical, but they’re also hopeful, with dispatches from an accidental bird sanctuary and an island-in-progress that aims to be Toronto’s first climate positive community. There is still time to avoid the worst outcomes, still time to build resilient communities in this city, still time to mitigate the harms that will come to the most vulnerable. But we need to start right now. This is, after all, an emergency.