The PATH is a windowless shrine to business wear buried deep beneath Toronto’s financial district. It is 30 kilometres of subterranean retail shopping, a labyrinth of gleaming marble and indirect lighting, a “city within the city” if a city started and ended in the duty-free section of its airport.

The PATH, despite the capitalization, does not actually stand for anything. It is not the “largest underground shopping concourse in the world,” though it has made that claim in the past. It is not, in truth, a single entity at all, but rather a collection of individual sub-basements owned by commercial landlords and connected, begrudgingly, by a series of wayfinding signs designed to disorient weary travellers, forcing them deeper and deeper into its terrazzo core.

The PATH has two primary selling points: it is protected from the weather, and it is connected to a collection of massive office towers that send armies of workers cascading down their elevator shafts at predictable hours, hungry and bored and happy to spend.

At least, that’s how it used to work.

For the past two years, the tunnels of the PATH have been eerily quiet. In the age of an airborne virus, “being indoors” is no longer the unquestioned virtue it once was; workers accustomed to the conveniences of home are resisting a full-time return to the office. And so, in spring 2022, there is one question on the minds of the hair stylists and shoe salesmen, pastry chefs, dry cleaners, baristas and other workers of the once thriving underground metropolis: what the hell is the PATH now?

Last Tuesday morning, as commuters at surface level cursed the season’s final errant flakes of snow, Jennifer Gregoire was already safely underground. The 62-year-old store manager locked stride with a security guard and the two chatted and laughed, sharing the easy rapport of long-time PATH workers. Gregoire unlocked the door and flicked on the lights, illuminating the window display of the Legs Beautiful store she manages in the Royal Bank Plaza. A collection of mannequin legs in various styles of pantyhose stood in the window next to a sign offering “50% off selected clothing.”

Gregoire has been working in the underground mall for 20 years, and she talks about the pre-pandemic crowds in the same awestruck, elegiac tone people use to describe the mighty herds of American bison that once roamed the plains. “When I started at First Canadian Place you couldn’t stop the traffic, there was endless traffic,” she said. She had four salespeople and they were open from 7:30 a.m. to 6:00 p.m, slinging hosiery to the professional class. Now it was just her, opening at 10:00 a.m, and hoping to get six sales a day.

“I don’t care what anybody says, it will never get back to what it was before,” said Gregoire. “There’s no way. The rush of people, the activities, the stores, they’re not even here anymore.”

That same sense of melancholy permeated the corridors of the PATH—the unsettling feeling that, maybe, the best days were already gone. Stylist George Gogos sat alone in the Blow Dry Lounge, perched like a cat in a red molded plastic chair, reminiscing about the pre-pandemic era in the eager, runaway-train cadence of a man who had not spoken to another human in weeks. Before, he said, everyone came to the Blow Dry Lounge—“lawyers, doctors, financiers, investment bankers. Party girls, tourists, travellers, all walks of nature.” The stylists had worked six abreast and it was “busy, couldn’t catch your breath, back-to-back.” Now it was just him. “We’re lucky that we didn’t close,” said Gogos. “We’re one of the lucky ones”

Signs of the less fortunate were everywhere. A barbershop sat padlocked and empty, leather chairs discarded in a corner. Restaurants had been hit particularly hard, and there were vacancies up and down the system’s food courts. “A lot of people that I knew left,” said Chris Madeira, the 59-year-old manager of the shoe store Peter Kaiser. Those who remain, she said, are “depressed, sad.”

For years, Madeira had been “Chris from Peter Kaiser”—someone repeat customers knew and treated almost like a friend. Now? She didn’t know what she would become. “Companies should force their employees to come back to work,” she said, though she knew that would never happen. “I don’t know if this will ever be the same.”

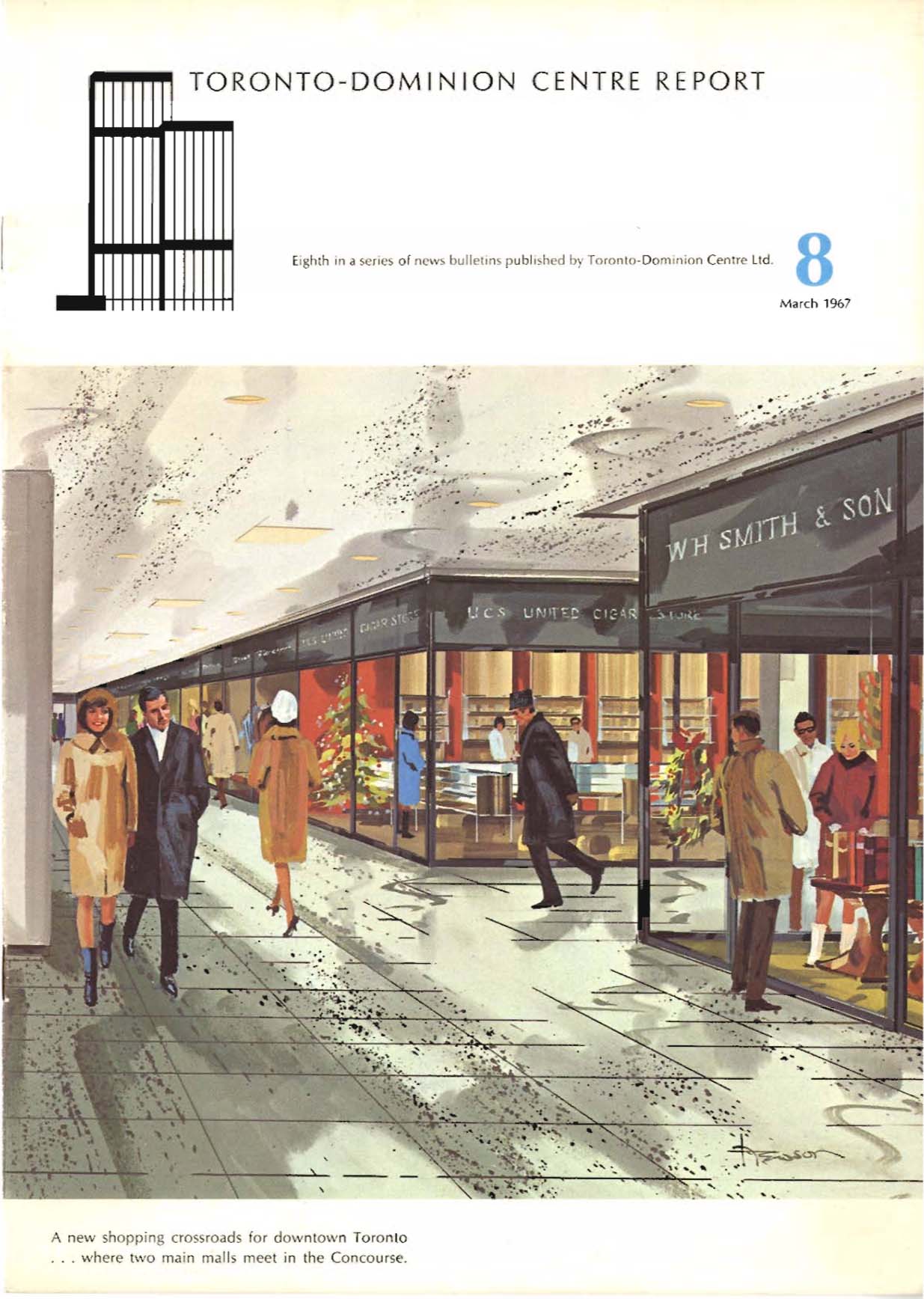

When the underground shopping concourse at the Toronto-Dominion Centre opened in 1967, it represented the height of the modern office experience. It was the first such mall in Canada and the “real beginning” of the PATH according to Laura Miller, a University of Toronto architecture professor. When Miller moved here 12 years ago, she became so obsessed with the city’s underground network—“a kind of terra incognita”—that she’s writing a book about it.

Designed by Mies van der Rohe, the entire office complex was a shrine to a specific vision of mid-century white-collar labour. Renderings from promotional materials show men in narrow ties gliding through an immaculate world of gleaming conference room tables and shops advertising their wares in a tasteful sans serif typeface designed by van der Rohe himself. In one rendering, a businessman pauses from his window shopping, swivelling his head to check out a woman in a fur coat and heels.

This was a world, according to the ad copy, in which “the tenant or visitor will find shops, restaurants, and services…in such variety and profusion that rarely will he (or she) have to go outside the Tower complex during the working day.” It was a vision of work as something wholly separate from domestic life, geographically and psychically. North American downtowns had transformed into “central business districts” that serviced the needs of office workers who commuted in from distant neighbourhoods, and held little of value for anyone else.

That vision of work, and of cities, was already dated before the pandemic; the work-from-home era has exploded it entirely.

Subscribe

Get our latest stories delivered to your inbox.

"*" indicates required fields

Since March, with the end of mask and vaccine mandates, business in the PATH has slowly been picking up. If you squint, you can see the faint remains of that old, glamorous vision of office living. Workers in navy blue suits with unbuttoned white shirts exchange firm handshakes outside McEwan. At Truffitt and Hill, men sit before gilded mirrors, getting their silver hair trimmed by barbers in bowties.

But the workers in the PATH are only back in the office provisionally. Most are working a day or two downtown and spending the rest of the week enjoying the comforts of home. “I’ve yet to meet someone who’s going five days,” said Sheri White, manager of the jewellery store Bitter Sweet. A customer interrupted her mid-sentence, a former PATH regular who now worked from home and happened to find herself downtown that day. “I don’t ever want to see the office again,” she said. “If I have to go back, I’d take an early retirement.”

In the white marble expanse of First Canadian Place, Michael Brooks sat elevated in a shoeshine chair, taking in the half-empty concourse. Brooks is the moustachioed CEO of RealPAC, a trade association for institutional real estate that represents many of the owners of the buildings that make up the PATH. The corporate landlords he works with had been devastated by the pandemic, he said, and he was eager to see any signs of a recovery.

Since his office had returned on March 8, “the traffic is way up,” Brooks noted. There were people in food courts again, line-ups at lunch. Traffic would continue to grow over the next months and years, he predicted. But the world, he had to acknowledge, had shifted. “It’s a bit of a cultural change,” he said. No one wore a tie anymore. He himself hadn’t worn dress shoes in two years. Workers had found flexibility at home—picking up their kids, throwing in a load of laundry at lunch, wearing whatever they wanted. And they were happy that way. “I do not see five days a week coming back.”

What that meant for the PATH—and for “business districts” across the continent—was the question Brooks, and everyone else, was still trying to figure out. “Maybe we will see more service-type tenants, like doctors and dentists,” he mused.

Laura Miller, the U of T professor, was thinking further outside the box. The model, she said, was the “ghost mall”—former palaces of commerce that have had to find new tenants as the retail industry imploded. That meant filling the space with occupants far less glamorous than those in the Mies van der Rohe renderings. “So, things like call centres, ghost kitchens,” said Miller. She thought about the PATH’s unique, windowless architecture. “What about hydroponic agriculture? Where do you need dark? Maybe film production facilities?”

At Legs Beautiful, Jennifer Gregoire didn’t have any clear-cut solutions. That day, the lunchtime “rush” had only brought two sales—a couple of old regulars who had returned after years away, happy to find her still behind the counter. “I had a few sales, so I’ve just gotta be happy,” said Gregoire diplomatically. “Just keep on rolling.”

Recently, though, she’d noticed something that stuck with her. Despite existing in the centre of Toronto, the PATH often feels hermetically sealed from the rest of the city. There are no welcoming street-level entrances, few attempts to attract anyone beyond its office worker constituency. The city, though, always finds its way in.

The kids on skateboards, Gregoire noted, were coming more often these days. She saw them in groups of fifteen or twenty, like some rolling portent of the PATH’s future—the rasp and clack their wheels echoing down the corridors, “hauling ass” as security guards chased them down the perfectly polished floors. Gregoire laughed, a PATH veteran ready to concede her time had come. “I say they need to close all the stores and make the PATH for all those skateboard kids.”