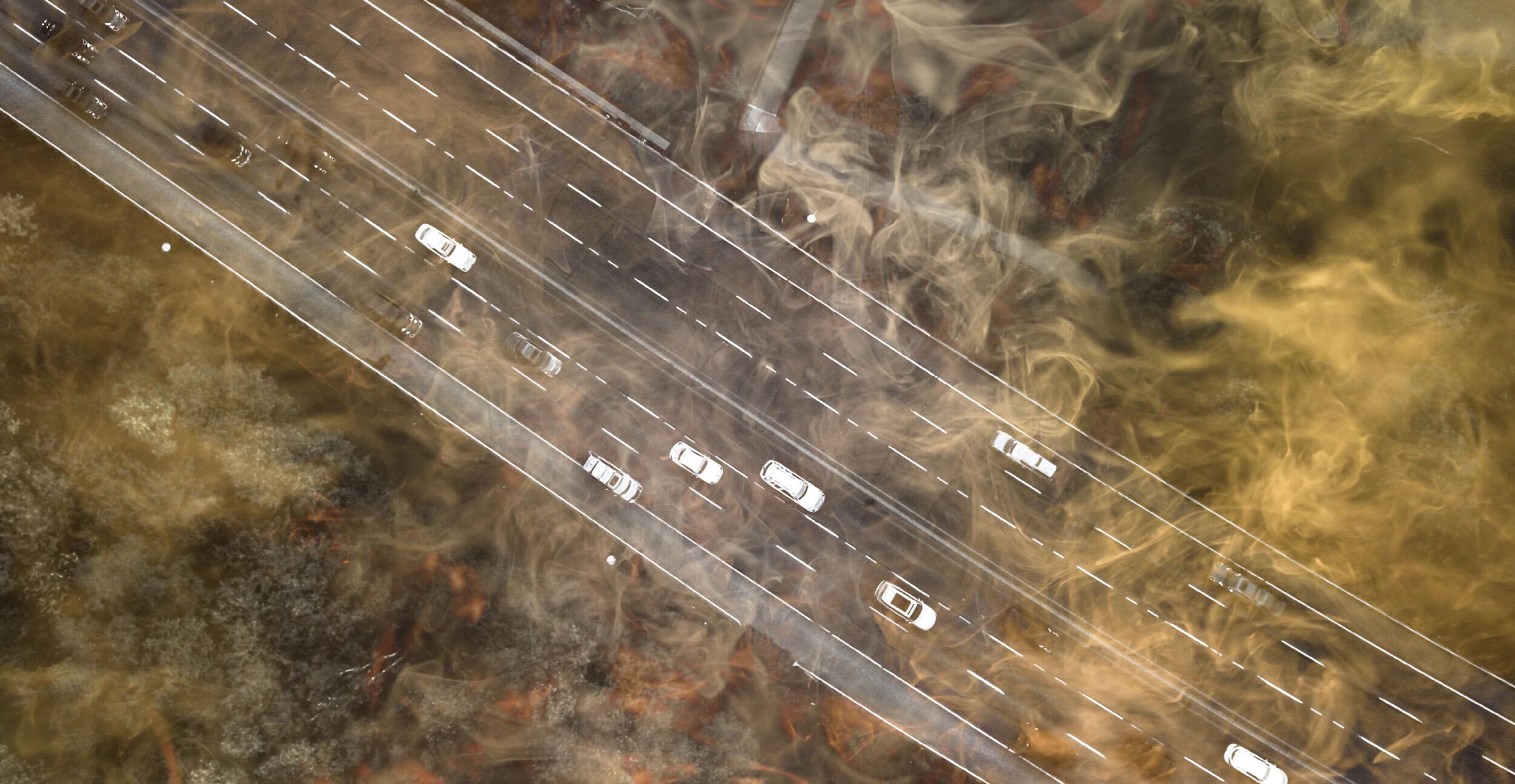

Foggy glasses, seasonal depression, road salt—all winter downers we’d prefer not to think about right now. Summertime salt should mean margaritas, sweat, and not much else. But while white-stained boots can be shoved in a closet come spring, the long-term effects of excessive road salt are unavoidable even after the last snowbank melts.

What we call road salt is, officially, big grains of sodium chloride. It’s cheap and easy to transport, which is why many parts of North America, including Toronto, have relied on it as a de-icer for nearly a century. But it also increases chloride levels in nearby rivers and streams, especially small ones that aren’t deep or wide enough for the salt to be effectively diluted. And those chloride levels are still high when no one can spare a thought for icy sidewalks.

“Research is showing that chloride that we’re using in road salt in the wintertime may actually be showing up in our freshwater systems throughout the summertime,” said Lauren Lawson, a PhD candidate in the department of ecology and evolutionary biology at the University of Toronto.

Lawson wanted a better idea of what road salt runoff was doing to Toronto’s waterways during warm weather, when many animals reproduce. So in the summer of 2019, she and a team tested chloride levels at 214 sites on four watersheds: Mimico Creek, Humber River, and Etobicoke Creek in the west end and Don River in the city centre.

“Looking at how many streams we have in Toronto—first off, it’s amazing,” Lawson said. “Some streams are completely concrete. And some streams are beautiful, where you don’t even know that you’re in the city.”

The duo assessed chloride levels at each site, then compared those levels to federal guidelines for chloride concentration. Overall, Mimico Creek had the highest chloride levels of the waterways they sampled. The larger Humber River had the lowest: the river has more greenspace around it in the city than the creeks do, Lawson said, and its headwaters reach north into the Oak Ridges Moraine, a protected area that’s part of the Greenbelt.

The effects of this overly salty environment on plants and animals isn’t straightforward. “You might think ‘OK, well, if you dump X amount of salt on your road and it goes into the river, all these organisms are going to die,’” Lawson said. “But it’s a lot more complicated than that.”

It’s all connected, of course: Lawson said that the sensitivity of freshwater mussels to high chloride levels is troubling for entire ecosystems, since their function as a filter system is crucial to some types of fish. But while some animals suffer, others seem unaffected. As some populations stay steady while others decrease or even disappear, the overall effect of rising chloride levels is “biotic homogenization”—decreasing biodiversity.

The American toad, for example, has adapted pretty well, with little to no effect on their life cycle or population. Other organisms have what are called “sub-lethal” effects: spotted salamanders are producing fewer and smaller eggs, as the stress that chloride puts on their bodies takes up energy needed for finding and eating food, and reproduction.

Then there are species like the redside dace, a minnow that’s endangered in Ontario. It’s suffering multiple stressors including loss of habitat, so it’s hard to pinpoint the effect of chloride. Lawson is now comparing chloride levels between waterways that still have redside dace and those that don’t. Almost 90 percent of the sites her team tested hit the chronic threshold for high chloride levels, meaning that at least five percent of the organisms in the water would be impacted over a long term. At over a third of the sites, a full quarter of the organisms would be affected.

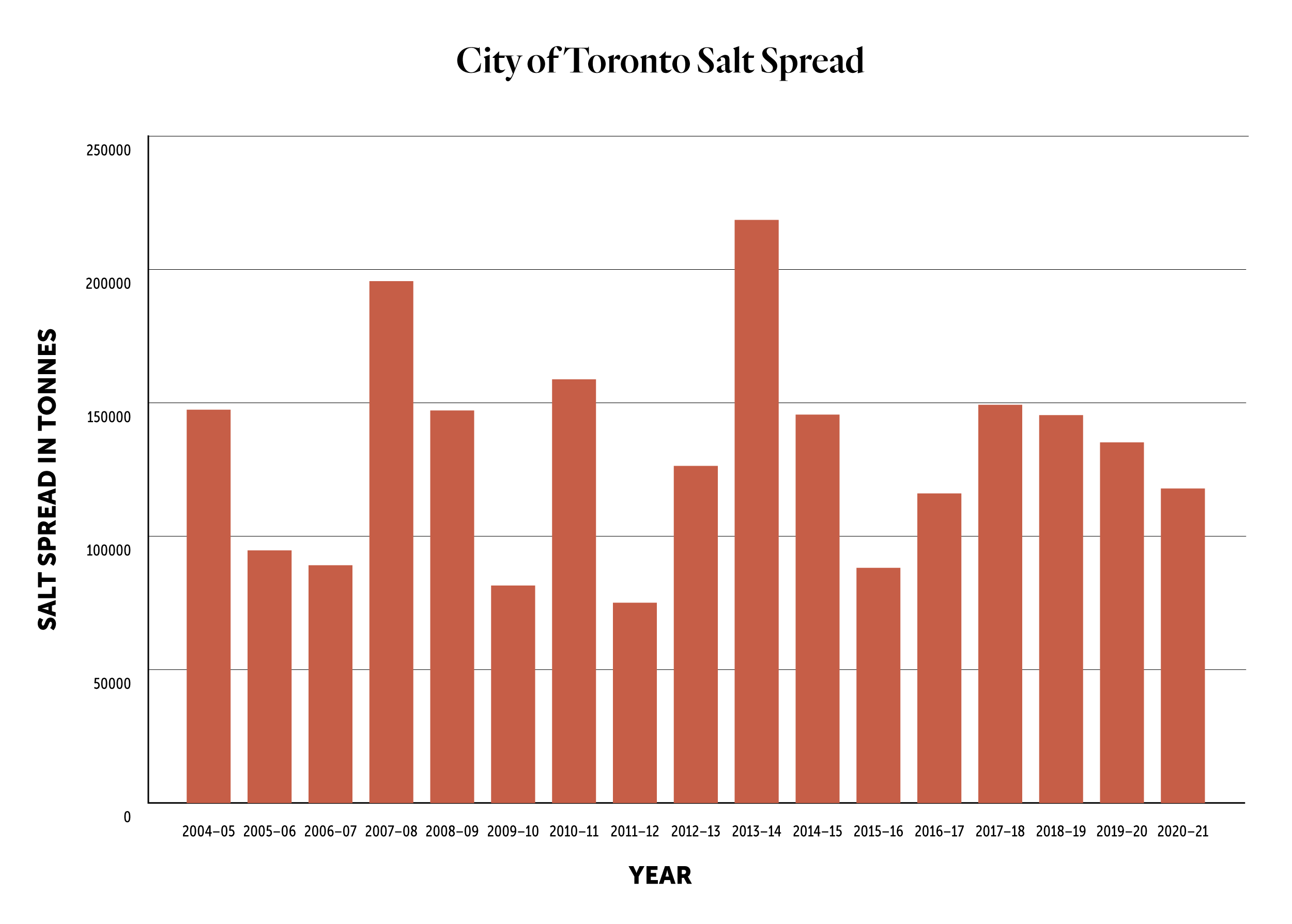

Rising chloride levels in Canadian waterways isn’t a new problem. In 2004, Environment Canada made it mandatory for any jurisdiction using 500 tonnes of sodium chloride or more a year to have a salt management plan. Toronto uses at least a hundred times that amount every winter. The city introduced its plan in 2005 and Jaime Thomas, senior program manager of winter operations and emergency services, said the goal of reducing salt use is a serious one.

Every year, operations staff attend “snow school” to learn about winter operations, including why and how salt use should be minimized: this year’s curriculum will include an introduction to new equipment with improved calibration technology for dispensing specific amounts. The city also uses a private weather forecast service that provides early, detailed information about oncoming storms. This allows for reduction techniques like pre-wetting salt, so it sticks better to roads, and pre-salting roads to help dissolve precipitation before it freezes.

Thomas also said Toronto is constantly testing new de-icing products, though managing citizen expectations about how alternatives perform can be an issue. She was surprised when connecting with a counterpart in Saskatchewan whose municipality uses gravel.

“I was like, ‘Wow, don’t you guys get claims?’ Because gravel, when it’s on a road it provides traction, but it also spits out and hits windshields,” she said, anticipating angry phone calls. But part of the reason for using gravel is that when temperatures dip more than 15 degrees below zero, even sodium chloride has a hard time melting ice. “In Saskatchewan, that’s an accepted consequence of the temperatures there, I guess, when salt is not effective.”

While Toronto hasn’t found a full replacement yet, alternatives to unadulterated road salt are in rotation. Liquid salt brine is used to pre-wet high-speed roads, especially when it’s very cold. That does make a difference, Lawson said. “Brine is salty, very salty,” she said. “But from what I’ve read it can reduce the overall amount of salt used by about a third.” The city also uses a mixture of salt and sand on sidewalks after plowing, but while this does reduce sodium chloride use, Lawson said sand runoff can also disturb the balance of nearby waterways.

So far, no mass alternative has presented itself. Beet juice is another buzzy option, but the healthy vegetable actually has a drawback: it can throw off the nutrient balance of rivers and streams. Four years ago, the city of Rosemère, Quebec, outside of Montreal, began a pilot project with wood chips treated with slow-release magnesium chloride, a de-icing chemical that’s less harmful to both waterways and infrastructure than conventional rock salt. Mayor Eric Westram said results have been mixed.

On small streets and sidewalks, the chips are a success. “As the snow melts, [the chips] float on top of the river,” he said, referring to the city’s major water body, the Rivière des Mille Îles that runs between the Ottawa and St. Lawrence rivers. “It ends up either in our filtration plant, where we treat water for drinking purposes, or it gets on the edges of the river and it disappears. It’s nothing,” Westram said.

But on streets where speeds are 40 km/h or faster, the chips don’t adhere to the road, instead sticking to tires and actually reducing traction. Residents’ expectations are an issue in Rosemère, too: Westram has heard some European cities don’t plow before putting the wood down, since chips stick better to snow than bare pavement. He suspects his office would be bombarded with calls if every speck of snow wasn’t removed from the roads.

As well, Westram’s early hope that wide adoption of the technology would bring prices down hasn’t materialized—the treated chips still cost 10 times as much as sodium chloride. That direct comparison isn’t fair though, he said, since another reason to reduce road salt use is that it causes infrastructural deterioration, which can also be expensive.

“When you put salt on it, cement gets eaten up,” he said. And indeed, road salt corrosion is one reason Toronto’s Gardiner Expressway is undergoing a rebuild that will cost about $1 billion. Such corrosion can be dangerous: the inquiry into the 2012 Algo Centre collapse in Elliot Lake, Ontario, heard that the mall’s carbon steel frame had been weakened, in part, by road salt.

Seventeen years after Toronto introduced its salt plan, sodium chloride use unfortunately hasn’t dropped very much. Thomas said there’s been about a 10 percent reduction since 2002. The exact amount used each year depends on temperature and snowfall, but since the winter of 2004-2005, the lowest amount of salt used over a winter was 75,049 tonnes, while the highest was 218,596 tonnes. The average between 2004-2005 and 2020-2021 was 131,283 tonnes a year—still an awful lot.

Lawson said we can’t blame everything on city trucks. Residents also need to stop encrusting driveways as if they were a fancy steak—and by the way, rising salt levels in waterways can also be a problem for those on low-sodium diets. She tries to spread some basic tips: road salt should be put down before, not after, snowfall, and in fairly small quantities. “A good measurement … is about a coffee cup’s worth for the standard driveway,” she said. “Which is a lot less than what most people use.”