On a sunny morning in April, Laurie Gunton was in a semi-detached house in north Toronto, carefully wrapping a series of clay sculptures for the trip down Yonge Street to their new home in a midtown apartment.

Gunton operates a local business called Smooth Move for Seniors that specializes in helping seniors downsize. They sort through a lifetime’s accumulation of personal belongings, selling, donating or disposing of unwanted items, and then packing, moving and unpacking the rest. They’ll even go to the pharmacy to pick up meds.

Helping seniors leave the home they’ve lived in for decades isn’t easy. “They second-guess themselves right up to the day of the move,” says Gunton. They look around and reminisce — sorting through the porcelain ornaments handed down from the previous generation, reluctant to leave the cabinet filled with memories of their husband or wife. Many know that they can’t handle living alone in a house anymore, but they hold out for as long as they can.

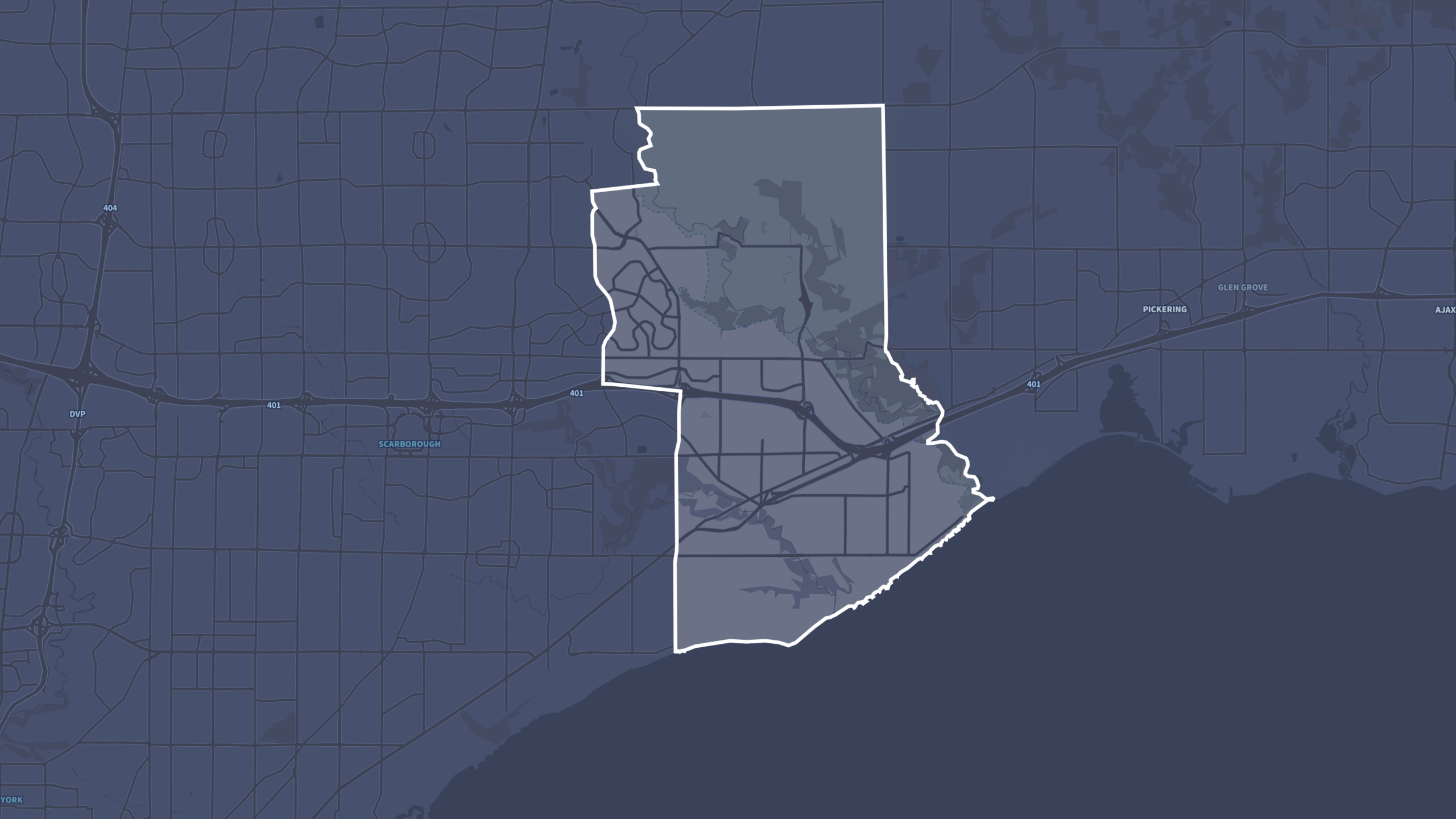

Nevertheless, business is booming. Gunton has set up shop in north Toronto, home to the highest proportion of residents over the age of 65, but she’s just one small part of a burgeoning industry, with companies with names like “Moving Seniors With a Smile” and “Downsizing Diva” and even an industry association. “Seniors are starting to understand that when they’re still healthy, that’s the time to move and go to an apartment or condo and not have to deal with the upkeep, the stairs and all those kinds of things,” says Gunton.

Much has been made of Toronto’s fascination with highrise living, especially among millennials and young professionals. But Gunton and her competitors have recognized that hidden beneath the broader trend towards vertical living is a population of aging boomers set to leave their homes. In the ten-year period between 2006 and 2016, the number of highrise apartment units headed by a senior grew by 28 percent. This is significantly more than the general increase in the seniors population, suggesting a shift in housing choices towards vertical living. Within the boundaries of the Toronto Central LHIN, the downtown core of the city, there are now over 200 apartment, condo, and co-op buildings where at least 40 percent of the residents are seniors. At UHN OpenLab, where I work with seniors to design ways to support healthy aging, I spend a lot of time in these buildings. When I walk their hallways, I’m often reminded of the reality that behind every other door is a senior.

According to the 2016 census, one in four Torontonians over the age of 65 live alone. That number prompted a recent CBC News headline to declare that Toronto is “getting older and more isolated.” But the truth is that the proportion of seniors who live alone has remained unchanged for over fifteen years. It’s hardly a new phenomenon. What’s new is that instead of living alone in their own homes, many aging Torontonians are now living alone alongside other seniors in the city’s growing number of highrise communities.

We’re witnessing a pivotal shift in the way seniors live in this city. Suburban cul-de-sacs are giving way to towering slabs of concrete — ad-hoc retirement communities in the sky. This is reshaping the social and physical environments within which aging takes place, and has profound implications for how we design services for seniors today and into the future.

When Arlene Noble left her home in Collingwood for an apartment in Toronto in 2015, the change felt overwhelming. The vibrant 76-year old former elementary school teacher and painter had started a local theatre company as a post-retirement gig in Collingwood. Moving to an apartment at Yonge and St Clair with her dog Luke meant leaving part of her life behind. When Luke died last January, her world shrunk just a little more.

“I lost my reason to get out and walk for an hour and a half everyday,” Noble says. She resisted getting another dog, knowing that apartment living is hard on animals. “If I was in a house, I’d have one in five seconds,” she says. She coped by signing up for another art class, going to the YMCA, and finding various reasons to get herself out the door. Then one day she met her neighbour John.

“He’s just a very sweet guy, 90 years old. I saw him turning his key and standing there and so we said hello, and then we said hello again, and then I can’t remember who invited who, but we had a glass of white wine together, and I found out that he likes vodka and soda,” she says, chuckling. “So every couple of months we’ll have a drink together. I phone him when I’m going to Sobeys and say, ‘Is there something I can pick up for you?’”

The two decided to exchange keys in case of an emergency. She’s also exchanged keys with two other women on the floor. And then there’s Cy and Ray from floor 23, both in their early seventies. Noble met them in the elevator on the day they moved in and then again in the laundry room downstairs. The trio have since become good friends. Cy goes to the local café everyday and often texts her, “Hey, I’m having a coffee at Aroma, are you free?”

Hidden beneath the broader trend towards vertical living is a population of aging boomers set to leave their homes.

For seniors like Noble, living in a highrise can help stave off the isolation that too often comes with aging alone. A 2014 report by the Government of Canada’s National Seniors Council found that isolated seniors are at a higher risk of engaging in unhealthy behaviours such as drinking, smoking, being sedentary, and having poor eating habits. They’re also more likely to experience falls, and are four-to-five times more likely to be hospitalized. Another recent study found that social isolation increases the risk of heart disease by 29 percent and stroke by 32 percent.

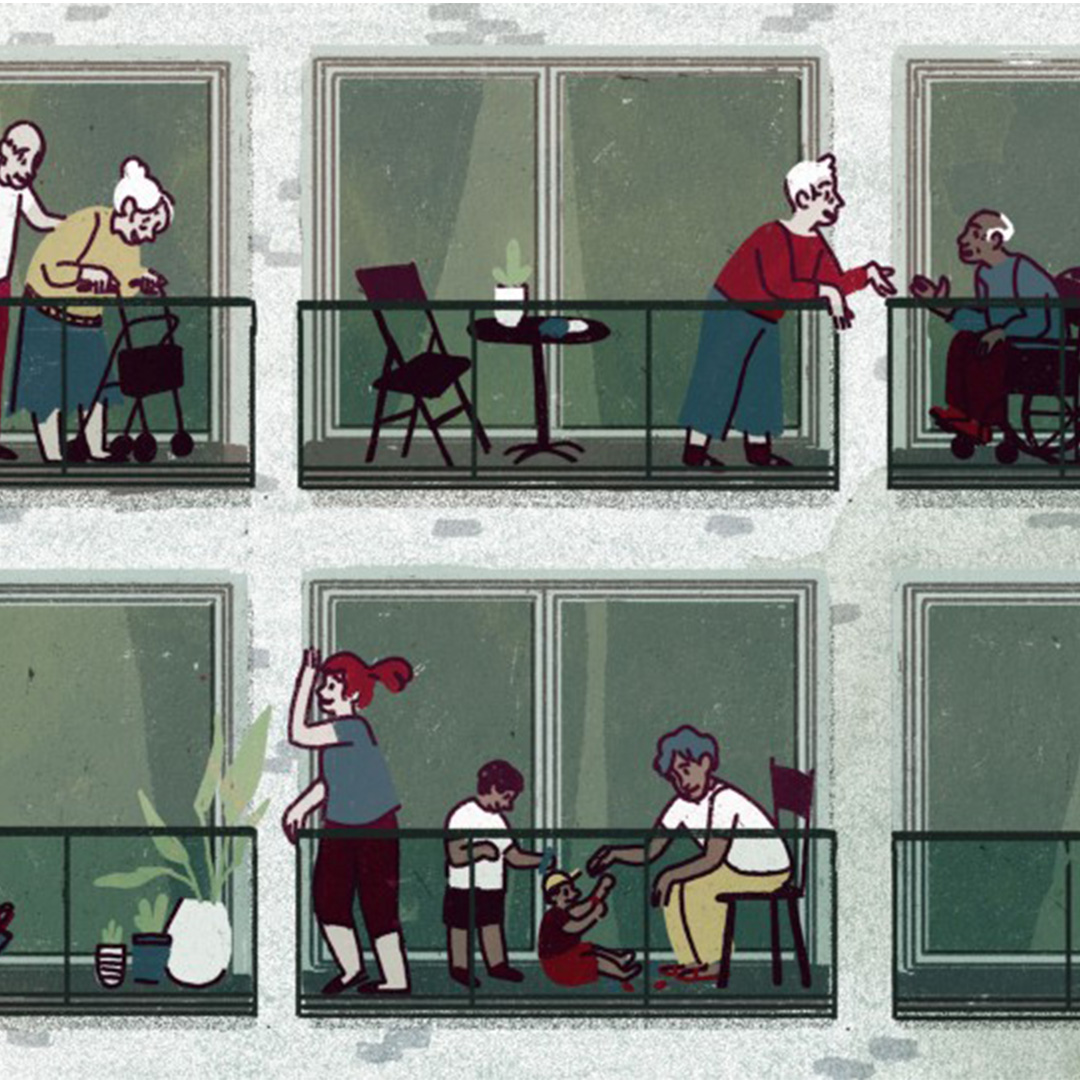

When seniors live right next to each other, separated by just a wall or a ceiling, it opens up possibilities for overcoming this isolation. Communal meals, social gatherings, and the kind of fortuitous interactions that happen when neighbours bump into one another in the laundry room can build social bonds and support healthy aging.

According to Jessica Govea, however, even living in close proximity doesn’t always guarantee social contact. Govea manages the maintenance team at a large apartment complex in the Bathurst and St. Clair area. The buildings have a good mix of families and young professionals, but seniors make up 47 percent of the tenants. With over 700 individuals over the age of 65, the complex is home to the largest number of seniors of any building in the city that’s not a long-term care facility.

Govea grew up in Guayaquil, a coastal city in Ecuador roughly the size of Toronto. When she arrived in Canada twelve years ago, she remembers being struck by how much Canadians kept to themselves. Back in Ecuador, her grandmother’s home didn’t seem to have a door. Neighbours would pop in to borrow an egg, to say hello, or for no apparent reason at all.

“Here, people are more reserved,” says Govea. “They don’t open up easily unless they really know you.” She says that this makes it difficult for a lot of seniors to build social connections, even though there are so many of them living in the same building. They experience the paradox of social isolation in the big city — the oxymoron of being alone, together.

Govea’s official job involves serving repair notices, attending to tenants’ complaints, and sending in the maintenance crew for work orders. But after ten years, she’s developed a rapport with many of the seniors in the building. They now call her for pretty much anything. “Sometimes they will come and tell me, ‘Jessica, I broke up with my boyfriend,’” says Govea. A resident recently confided that she has Alzheimer’s, but didn’t want anybody else to know. Seniors who live alone often ask her to check in on them at a certain time during the day, just to make sure that everything is okay.

“My job is maintenance administrator, but I think I’m also a counselor-slash-psychologist-slash-you-name-it,” she jokes. Govea is proud of being able to give seniors in the building that extra boost they need to keep living independently, but it’s all informal work she does in addition to her job. To truly support the growing number of seniors living in apartment towers, it’s going to take more than the goodwill and labour of people like Govea. It’s going to require a substantial reconfiguration of the formal system of supports for seniors — a change that starts with questioning some of the fundamental assumptions behind the way seniors services are designed and delivered.

In 1979, the Letter Carriers Union of Canada, Local 190, began a modest pilot project in the Weston neighbourhood of Toronto. The idea was simple: letter carriers on their daily route would keep a watchful eye on seniors living alone. If there was a pileup of mail or if they noticed something peculiar, they would notify a family member, the family doctor, or the community agency on file.

“Sometimes they’re just away on holidays,” one mailman told the Toronto Star. “But one time there was a woman who had had a stroke, and because of the service she was found and taken to hospital.” Within 3 months, 150 seniors in Weston had signed up for the program. Just three years later, letter carriers were keeping an eye out for 3,000 seniors across the entire city.

The program was an elegant solution to a complex need. Who but letter carriers could go door-to-door, neighbourhood-by-neighbourhood, on a daily basis? Despite the rapid success, the program eventually stalled, and disappeared altogether over the coming decade after a series of postal strikes. A quarter of a century later, efforts are now underway to revive it, this time as a paid service.

But Toronto in 2018 is a different place. Rather than reviving antiquated programs based on the paradigm of suburban living, we need to adapt to the reality of aging in the 2010s.

Some of these changes are relatively simple. Instead of personal support workers hopping on the bus to go from client-to-client, dedicated workers could serve multiple people in the same building, saving costs and reducing the chaos of several agencies going into the same home without talking to each other.

It’s an advantage that Stacy Landau, CEO of SPRINT Senior Care, has been exploiting for some time now. SPRINT is the largest provider of community support services to seniors in north Toronto. Their supportive housing program provides on-site services to help seniors with their daily activities at four Toronto Community Housing buildings.

“In one of our buildings, on Eglinton near Yonge, everyone thinks it’s full of these young people, but it’s all seniors,” says Landau. Her staff, who are stationed right in the building, provide personal care, respond to emergencies, do meal preparation, laundry, security checks, and monitor medication. Although many of her clients need a lot of assistance with daily life, Landau says some just need a little help here and there and it’s not fair to pay staff for 15 minutes of service at a time. Within an apartment building, she’s able to book staff for two-hour chunks and have them serve multiple clients.

The way Landau sees it, the system needs to move much more quickly to take advantage of urban density. But there are legacy issues that often get in the way, many of which were conceived during a different era. Landau would like to convert personal support workers from doing shift work to full-time equivalent positions who serve a very tight geography, such as one apartment building. But eliminating paid travel time — which makes up a good portion of workers’ take-home pay — and absorbing it into the salary scale is easier said than done. Like all entrenched systems, it’s difficult to change overnight.

Many seniors experience the paradox of social isolation in the big city — the oxymoron of being alone, together.

The built environment is another legacy issue. Many seniors flock to apartments in older buildings because of their larger size and cheaper rent, the so-called “post-war apartment towers” built between 1945 and 1984 that are scattered across Toronto. The buildings were the result of planning policies that encouraged the modernist “tower-in-the-park” housing model — apartment clusters built in single-use residential areas, often far from amenities. In contrast to the present-day emphasis on mixed-use development, these bedroom communities were heavily dependent on the automobile to connect the home in one part of the city to the workplace and services in another.

For seniors with reduced mobility, this kind of physical isolation can perpetuate social isolation. Older buildings also face internal issues like broken elevators, which affect seniors more than the general population. A United Way survey from 2011 found that residents of a third of these buildings reported frequent elevator breakdowns, and the problem was worse in buildings located in low-income neighbourhoods. The study also found that close to half of the buildings had neither common rooms nor recreational spaces that encourage social interactions. For seniors who already have a hard time getting out, this makes it too easy to just become shut-ins.

While not geared specifically at the seniors population, the City of Toronto’s Tower Renewal initiative includes several programs that can make the built environment in these aging towers more accommodating to seniors’ needs. This includes RentSafeTO, a bylaw enforcement program rolled out in 2017 to ensure that landlords maintain things like elevators in working condition. The city also recently brought in Residential Apartment Commercial Zoning, allowing buildings sitting on land previously zoned as residential to have shops, cafés, health clinics and other small businesses that make them more liveable.

Today, 143,000 Toronto seniors live in buildings five storeys or taller — more than a third of all seniors who still live independently. And this number is on the rise. No other Canadian city comes close to matching the urban density seen in Toronto’s seniors population. This city is uniquely positioned to take advantage of this phenomenon to tackle long-standing problems like social isolation, and fragmented home and community services. By finding seniors where they live and helping them stay there for as long as possible, we can alleviate pressures on the long-term care system, while avoiding the need to make massive investments in capital development.

The city, for its part, is in the process of taking over the 83 seniors-designated buildings from Toronto Community Housing and placing them under the stewardship of a new entity that it hopes will do a better job of integrating seniors housing and services. The recently approved Toronto Seniors Strategy, Version 2.0 includes initiatives to better support “apartment buildings or housing developments that house a high concentration of seniors.” At the provincial level, the Ministry of Seniors Affairs announced in May 2018 that it was investing $8.8 million to support a number of naturally occurring retirement communities—apartment buildings where many seniors already live close to one another. (Full disclosure: I was involved in some of the consultations that resulted in these municipal and provincial policies). It remains to be seen what happens to the provincial initiative with the change in government.

With just another ten years to go before the peak of the boomer generation moves into retirement age, there’s little time to waste. The future of aging in the city hinges on the decisions we make today.