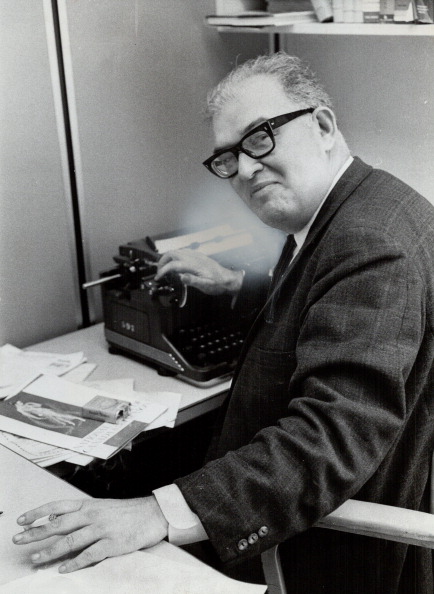

On the evening of Friday, March 26, 1971, civil war had been raging in East Pakistan and news was breaking of a covert FBI program to spy on and harass dissident American citizens. But the lead headline on CBC TV’s The National that night was, “Nathan Cohen is Dead.”

Who the hell was Nathan Cohen? He was a Toronto theatre and film critic and, believe it or not, one of the most famous people in the city, perhaps the country. Today, when most media outlets have cut arts staffs to the bone, and social media and algorithmic recommendation engines threaten to usurp professional criticism altogether, it’s hard to imagine a reviewer anywhere whose death would top the news.

Born in Nova Scotia, Cohen’s first gigs in Toronto were with Jewish and Communist publications before he found a platform on the CBC in the late 1940s, talking about plays and movies on radio, and then hosting the national TV panel show Fighting Words. He joined the now-defunct Toronto Telegram in the late 1950s before moving to the Toronto Star, swashbuckling about town with the cane he adopted as an affectation, running up expense accounts, and by turns titillating and scandalizing grey old Toronto the Good.

He would champion startup Canadian theatres, then turn on them for betraying their promise. He was a thorn in the side of the nascent Stratford Festival. As retold in posthumous appreciations in Toronto Life and The Ottawa Journal, when Cohen was asked, “Do you really think the hundreds of thousands of people who loved Brigadoon are wrong, and you’re right?” he instantly fired back, “Yes.” It’s said he wined and dined Richard Burton and Elizabeth Taylor one night, then savaged their touring production of Hamlet in print. Invited to watch a reworked version, Cohen trashed it again. Finally, Burton asked him to come to New York to see another remount. Cohen reportedly answered, “Now look, how much do you think I can take?”

The question that always plagues local arts criticism is how much to nurture a fragile arts scene, and how much to demand higher standards and more meaningful experiences. In his boldness, Cohen seemed to achieve both, at a time when the original and professional Canadian theatre he wanted barely existed yet. A decade after his death at only 47, the critic himself was the subject of a play titled Nathan Cohen: A Review, by Rick Salutin at Theatre Passe Muraille, the kind of company Cohen had been calling for but never got to see in full flower. Today, a studio at Young People’s Theatre is still named for him, as are the Canadian Theatre Critics Association’s annual awards for excellence.

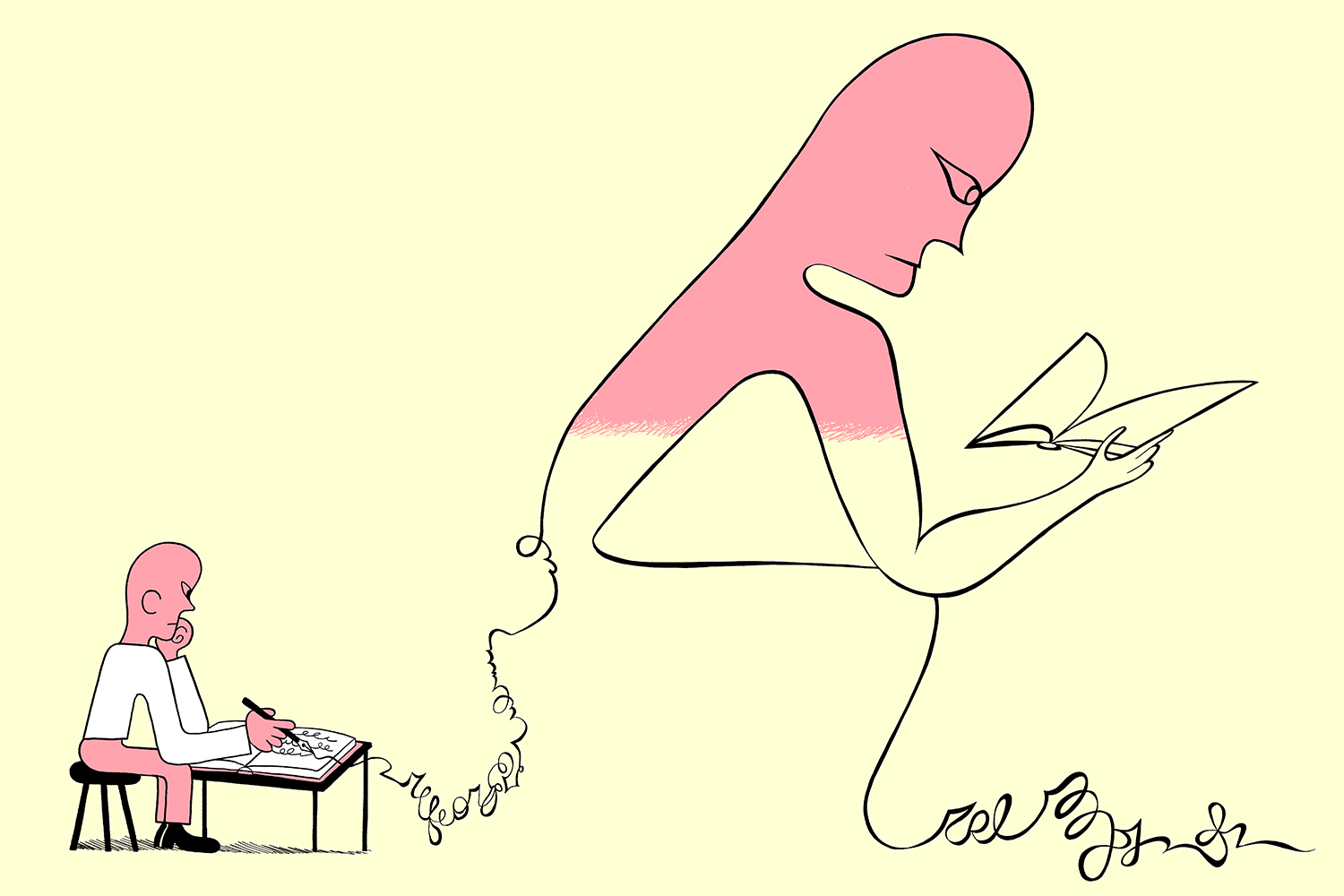

As a cultural critic myself, but also as a Torontonian, it’s hard not to envy those rare concrete signs of a critic’s impact on an art form. More often, we are an unglamorous but essential part of the cultural ecosystem. Our opinions and our authority to hold them are constantly called into question, understandably enough. But good critics don’t just amplify what’s happening in arts scenes; they reflect cultural works and trends back in historical and aesthetic context, illuminate connections between art and the rest of life, and push forward conversations about what’s worth doing culturally and why. Critics dig into the things that entertain us in order to propose ways of seeing who, what, and where we are.

Introducing a collection of pieces by onetime Globe and Mail film critic Jay Scott, who died of AIDS-related causes in 1993, the critic and journalist Robert Fulford once wrote, “Critics shape the context in which artists reach their public, and Scott did as much as anyone to create a sophisticated audience for film. In a sense, the audience found itself through Scott. By becoming the centre of discourse, he helped moviegoers in Toronto to make connections among themselves and form an articulate community.” That’s true not only for audiences but for the artists who then arise to serve their heightened appetites and to challenge their blind spots. In the 1980s, that included Toronto filmmakers like Atom Egoyan, Bruce McDonald, and Patricia Rozema, to whom Scott responded in turn.

Toronto now is a vastly more diverse and complex place. Assessing its arts scene demands a wider range of voices than the predominantly white and male critics of the print era. (Of course, it should have had them then as well.) But we’re worse off if none of them can dream realistically of becoming the next Nathan Cohen or Jay Scott—someone who not only points the city’s collective attention where it’s merited, but whose ideas spawn others’ ideas, whose arguments spin off into chains of debate, who offer things worth fighting about and fighting for.

Art + Money

Subscribe to our free newsletter to get our stories delivered directly to your inbox.

For a Cohen or a Scott to emerge requires an entire milieu. From the 1970s through the 2000s, as the veteran music journalist Nicholas Jennings recalled to me, “All of [the newspapers] had critics in all of the fields—television critics, movie critics, drama critics, dance critics, and then within music, you had classical, pop, jazz. Newspapers had multiple specialists who were covering all the different areas of the arts.” And that’s not to mention the alternative weeklies NOW and Eye, a host of arts magazines (short-lived or long-lasting, niche or general, elitist or politicized), as well as coverage on CBC radio and television, TVOntario, and sometimes the private networks as well. “It was a godsend,” said Jennings, “for anyone with an interest in culture and in the arts.” Former Globe film critic Liam Lacey, who started covering the arts there in 1979 and left in 2015, told me he estimated that in the mid-1990s there were about 25 staffers covering arts at The Globe, with both reporters and critics (separate jobs, importantly) on each major beat. Today’s arts sections are ghost towns by comparison.

It’s no mystery why the boom times in arts journalism ended. Like the rest of the media, the field has contended with the collapse of its advertising-based economic model, as tech platforms have annexed most of the market. And even at its past heights, editors and publishers often saw arts coverage as the most expendable part of the equation. Jennings told me that while he was a feature writer and music critic at Maclean’s magazine from 1980 to 2000, the arts editor had to fight for every story at editorial meetings, and those pages were the first to go in an advertising shortfall. More than a few veteran journalists remembered their colleagues in news referring to the arts section unaffectionately as “the pansy patch.” (Yes, that was a gay slur.)

Today, that scepticism towards arts coverage is all too often backed up by data on click rates and reader engagement—if all a publisher cares about is the bottom line, rather than representing the fullness of human experience, the arts are an easy cut. In retrospect, the peak 40 to 50 years of robust, wide-ranging arts coverage in the mainstream media might be what we look back on as the aberration. Why was it able to happen? Obviously there was advertising money to be made, but as well, with the expansion of post-secondary education in the post-war years, there was a fresh hunger for broader cultural horizons. And as local as well as national institutions, media outlets felt some responsibility to represent that aspect of the community. Until somewhere around the early 1970s, though, earnest arts coverage in Canada was reserved mostly for prestige outfits like the symphony and ballet; pop culture was more the domain of quick-hit reviews and showbiz gossip columns, like the Star’s snappy Sid Adilman with his “Eye on Entertainment.” It was the rock generation, both on staff and in readership, that came along to bring more serious attention to the so-called “low” arts of pop music and film.

In Canada, that shift was combined with the energy of post-1967 cultural nationalism, which really involved making an argument for the value of having cultural products of our own at all. Independent publishing, music, theatre, and more were rapidly expanding, with generous government arts funding. The breakthrough 1960s Toronto music writer Ritchie Yorke eventually moved on from covering the Yorkville scene to help lobby for the creation of the Canadian-content rules in music broadcasting. (By then The Globe had already turfed him for being too close to John Lennon and Yoko Ono’s peace campaign.) Not everyone went that far, but cultural debates of all sorts, especially in Toronto, were affected by an ongoing debate about the “Canadian identity” and who would define and determine it. The nation was striving to grow out of being psychologically a British colony without inadvertently becoming an American one. It took until about the 1990s, after all the rounds of constitutional reform and free-trade debates, for people to tire of the national-identity question and perhaps decide that leaving it unresolved would be the most Canadian thing of all.

Meanwhile, in response to that initial 1970s surge, a younger cohort of writers—still boomers, but of the punk generation—wanted to expand the boundaries still further, with the founding of NOW Magazine in 1981. “The Star’s Peter Goddard wrote about rock in a very professorial way,” co-founder Michael Hollet told me recently. “It was not sex and drugs and sweat. It was ‘considered,’ and it was ‘fine.’…We created NOW to be within the scene. We wanted to do the exact opposite.”

Good critics don’t just amplify what’s happening in arts scenes; they reflect cultural works and trends back in historical and aesthetic context, illuminate connections between art and the rest of life, and push forward conversations.

With that mandate, NOW also had its more hyper-local version of Canadian nationalism. “At the time in Toronto, there was a real New York City fetishization, like all the artists felt they had to go to New York to be validated,” said Hollett. “We were like, ‘fuck New York, we’re just making it about Toronto,’ and it’ll be valid by judging it in the context of our city, and measured by us.” There’s no doubt that being on the cover of NOW, or later Eye, was a milestone for many local artists. Hollett said he’s heard that even Drake has his first NOW cover framed at home.

In those flush years of nightclub advertising and thick classified-ad sections, NOW’s bigger challenge was to diversify its own staff, especially in terms of race. By the later 1980s and 1990s, Hollett said he insisted on seeking out critics of colour—including Cameron Bailey on film, now the director of the Toronto International Film Festival, and Matt Galloway on music, today a longtime CBC radio morning host. “For these schmuck people that object to notions of ‘quotas,’ to diversity being explicit,” Hollett said, it’s just too “easy not to see others….If you’re not explicit, you end up filling that seat with somebody you already know, somebody who’s around.” For a white editor, that would usually mean someone white.

Mostly, however, it’s a bitter irony that Toronto arts criticism would begin to include significant (and still insufficient) proportions of people of colour only by the 2000s. Just in time for the great shrinking to start.

At least, that’s the arc as far as I can figure it out. In fact, there are frustratingly few sources available on the history of criticism in Canada, especially on pop culture. And because journalism is so biased in favour of the current and what’s coming, it often loses track of what came before. Lacey told me that when the Toronto Film Critics Association was formed, “We established an award [named] for Clyde Gilmour, who was considered to be the first film critic in the city.” But looking back in The Globe and Mail’s files, Lacey discovered that the paper had had another 1950s film writer, named Betty Lee, as well as Wendy Michener, the arts-scenester daughter of a governor-general.

From early in the 20th century, in fact, women played a role in arts journalism that is often forgotten because they might have had those jobs part-time, or as a sideline to other duties at a publication. “They were given these ‘little’ assignments that weren’t considered particularly important,” communications historian Zoe Constantinides told me. “Then, when the field started to professionalize more, and people started getting paid better for reviewing films or just covering film culture, the positions became more and more occupied by men.”

Broadcasting Taste, Constantinides’ 2016 doctoral thesis on the history of “film talk” in Canadian broadcasting, is the kind of work that needs to be mirrored in other fields of Canadian criticism. I delighted, for instance, in her depiction of the rivalry in 1950s-era CBC Radio film reviewing between the self-consciously populist “everyman” Gilmour and the artier and supposedly more snobbish Gerald Pratley, each of whom also covered films in print. A sort of forerunner to the later, avuncular TVO movie-program host Elwy Yost, Gilmour would become the more beloved figure of the two; his CBC music program Gilmour’s Albums ran from 1956 to 1997, making it perhaps the longest-running in the broadcaster’s history. But as Contantines writes, Pratley’s values of “art over commerce, cinema as an international and unifying force, and the importance of authenticity” would “come to characterize criticism of Canadian national cinema more generally.”

The question that always plagues local arts criticism is how much to nurture a fragile arts scene, and how much to demand higher standards and more meaningful experiences.

“An age that has no criticism,” Oscar Wilde once wrote, “is either an age in which art is immobile, hieratic, and confined to the reproduction of formal types, or an age that possesses no art at all.” But Wilde couldn’t foresee an age like ours, in which art is not only mobile but wildly scattered across an all-encompassing infosphere, jumbled up in a cacophony of news, falsehood, memes, and polemic, in a constant cascading jumble. What feels scarce is space for contemplation and perspective, imaginative speculation and play.

These are pluses and pleasures that criticism at its best can offer, as a subgenre of writing that runs parallel to the tumult of cultural activity, in the footnotes across the bottom of the turning pages and seasons. Short bursts of verbiage or looped video clips on social media are not a substitute, nor is the “users who liked X also like Y” autopilot of streaming algorithms.

It can be difficult to find causes for optimism in the landscape of criticism today. The Star, the largest paper in Canada, has six culture writers now, though some double as editors, plus at least three freelancers who contribute arts coverage on a weekly basis. My former employer The Globe and Mail has five full-time arts writers, only two of them primarily critics, in film and in theatre. The Toronto Sun/Sun Media has only one full-time entertainment writer. The National Post has precisely zero.

The alt-weeklies are gone, except for the lingering ghost of NOW’s content-poor website under new ownership. Sites such as blogTO post occasional arts news/listicles, not criticism. A handful of hardy arts magazines survive, such as the indie-rock-etc. tabloid Exclaim! and, surprisingly, experimental-music journal Musicworks, which comes out in print three times a year with an accompanying CD. CBC Radio still tries to hold up its end, most recently adding the excellent arts discussion program Commotion, hosted by arts journalist Elamin Abdelmahmoud (I’ve been a guest there). Many of us (myself included) have launched email newsletters to try to build up our own niche audiences and earn some sustenance income.

As Lacey said to me, it’s important not to get jaded about the fact that more than ever before, each reader has easy access to the best criticism being written anywhere. But that doesn’t do much to enhance a specific cultural consciousness for Toronto or any other smaller centre. Just as in print and TV news, local coverage increasingly draws the short straw. Forget about in-depth criticism—it’s striking how much we lose simply by not having a central place for comprehensive event listings. I know I’ve repeatedly found out only after the fact that a favourite artist was performing in the city, and plenty of people have told me the same.

Hollett is trying to partly fill some of that gap with his latest venture, the monthly NEXT magazine. But both he and Constantinides observed that something about the media environment, whether it is the scarcity of opportunity or the scrutiny of social media, tends to tamp down young critics’ nerves. “There’s a really persistent expectation in digital media, whether it’s a podcast or print or video, to play the role of ‘everyperson’,” Constantinides said. “How do you distinguish your voice while you’re also trying to sound like everybody else? How do you say something with authority without appearing to embody any authority? And then that also comes into play with the different identities and who has space to speak and who’s being listened to.”

You could counter that this problem of credibility stretches through the whole history of pop-culture criticism. It’s a job for which there’s no sure professional qualification except an irrational confidence and dedication, and ideally some intellectual and verbal dexterity. The UK film scholar Mattias Frey argues in his influential 2014 book The Permanent Crisis of Film Criticism: The Anxiety of Authority that between changing technologies, intellectual fashions, and media models, critics always have been declaring that the field is on the brink of disaster. In the late 2000s and 2010s, the threats were blogs and then Rotten Tomatoes. In the 1980s and 1990s, it was the thumbs-up-or-down movie-reviewing TV franchise of Siskel and Ebert. In the 1950s, it could be TV itself or the “middlebrow” influence of, say, the Book of the Month Club. We’re critics, after all—we do tend to have an eye for problems.

I try to derive some comfort from that thought, amid the never-ending news of media layoffs and closings. After all, local critics and cultural-personal essayists of conviction do keep cropping up, such as Soraya Roberts, Tajja Issen, and The Walrus’s Connor Garel. But I still keep wondering about the possible correspondence between the scarcity of arts coverage and criticism in 2024 Toronto and all the festivals, venues, scenes, and other arts initiatives here that seem to be gasping for breath. Would that we all could have as few anxieties about our authority as Nathan Cohen, that magnificent son of a bitch.

Our Art + Money issue was made possible, in part, through the generous support of Toronto Arts Council. All stories were produced independently by The Local.