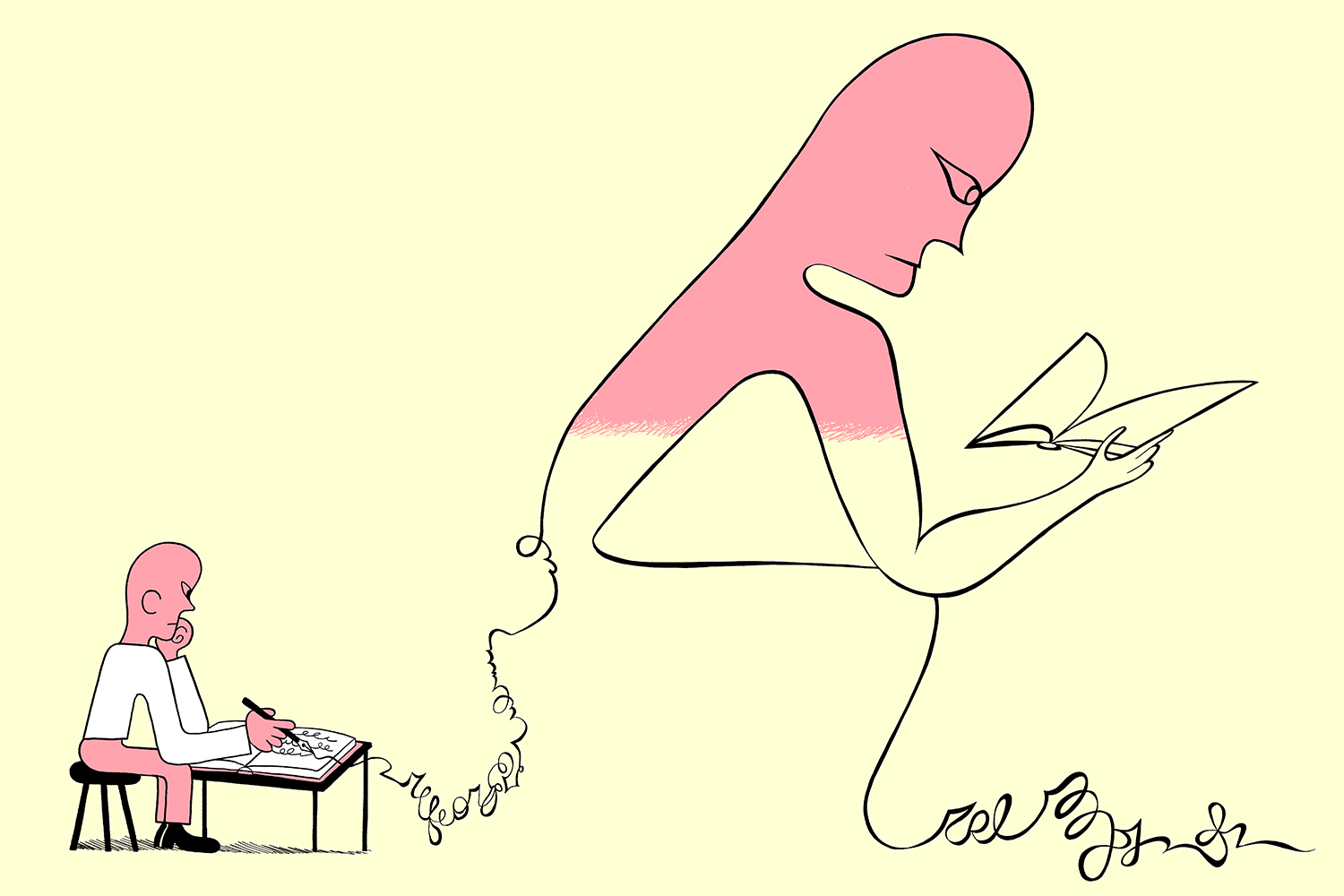

I sometimes think that Canada is the worst place in the world to be an artist. I sometimes think that this country might actually be anti-art. You would think that a war-torn village or some lethal dictatorship would actually be more culturally inhospitable, but it’s precisely the commitment to projecting absolutely no friction that makes Canada so inimical to art, a discipline borne out of confrontation. Our flag should not feature a maple leaf, but a small boat that refuses to be rocked.

This country is run by pencil pushers who insist on everyone drawing within the lines as the people at the top keep narrowing the borders in their favour. And no one says anything because of how impolite that would be. It is impolite to admit that this country’s richest culture has been shoved aside for what was once characterized to me as “the big boring middle that’s taking up space.” The real texture of Canada—all the Indigenous people, all the immigrants, all the races and classes and genders and sexualities—has been traded in for, essentially, a white sheet of paper. And a white sheet of paper is fragile, unstable by design. It is liable to crumple under pressure. And that’s where we are now.

Take Toronto, home to many of the largest arts institutions in the country. In the past few years—accelerating over the past few months—these institutions have started to show huge, in some cases foundational, cracks. First there was the Toronto International Film Festival going through round after round of layoffs, initially losing a number of executives and then its biggest sponsor, Bell, in August. That same month, it was announced that Artscape, which offers space for artists to work, was going into receivership. Then came the reports that the Harbourfront Center did not have sustainable funding, that the Toronto Fringe and the Luminato Festivals had both executed major programming cuts, that Scotiabank had dropped its lead sponsorship of the Contact Photography Festival. In March, Hot Docs programmers quit en masse, followed a day later by hundreds of Art Gallery of Ontario workers launching a strike.

One by one, all of the cultural organizations in the city appeared to be crumbling and the story always seemed to be the same—executives with disproportionately high salaries corporatizing what had once been valuable art havens into unmanageable business ventures.

This country’s characteristic non-confrontational posture has permitted an executive class to standardize its incompetence to the point of collapsing an entire industry.

The situation at Hot Docs is illustrative. On March 25, one month before the launch of this year’s festival, 10 programmers resigned together. In a joint letter, they described an “unprofessional and discriminatory” workplace marked by a breakdown in protocol and communication and breaches of contracts. They took their concerns to escalating levels of leadership, which denied their request for public transparency and went on prioritizing the festival instead. Per the letter: “In order for a world-class event like Hot Docs to remain relevant and thriving, the programming team believes it must be kept accountable and transparent.”

Following the news of this exodus, a highly circulated Reddit post purportedly from an unnamed former Hot Docs employee depicted an organization that sounded interchangeable with a number of others in the city. It described a place that had started out as a small outfit where programmers felt valued, despite the low pay and high work volume. The pandemic provided a convenient excuse for what, over the years, had become an increasingly stratified corporate structure, in which executives maintained high salaries while managers scrambled with tightening resources and everyone below them—notably those doing the actual arts-based work on which the organization was founded—bore the brunt of the squeeze. “What does it mean for one organization to build up its own administrative and financial capacities on the backs of the cultural community it’s trying to support?” asked Caitlin Jones in a Momus piece about Artscape, which could have easily been about Hot Docs. “Who benefits most from this top-heavy model?”

The answer is, of course, the top. Yes, this is another story of late capitalism, but its texture is particularly Canadian. This country’s characteristic non-confrontational posture has permitted an executive class to standardize its incompetence to the point of collapsing an entire industry. And in the end, those most affected—the cultural workers who define that industry—have been forced to confront what the country has repeatedly failed to.

“Our mission is to empower storytellers,” said Marie Nelson, the president of Hot Docs, at a press conference for the festival within days of her staff’s mass resignation. The line was so vague and generic that she could have been talking about anywhere. And that’s the point. The former Disney exec from Baltimore was hired just like an Australian was hired for Luminato, just like the same small number of local execs are shuffled—sorry, “restructured”—from corner office to corner office in Toronto’s culture industry, because everyone at the C-suite level is considered equivalent. By the same token, the workplaces they oversee are considered interchangeable. The problem is that each arts institution is a specific ecosystem. Constantly hiring leaders from outside, not promoting from within or even considering the internal nuances of particular organizations, means none of these executives have any actual relationship to these organizations. They do not understand nor do they have any real stake in their cultural value, which means they have no real investment in them.

Art + Money

More stories from our Art + Money series throughout April. Subscribe to our free newsletter to get them delivered directly to your inbox.

According to documents obtained by The Toronto Star, Hot Docs was accused internally by its programmers of “grave mismanagement.” One internal letter got more detailed, stating that the workplace had become one of “chaos, isolation, mistrust and disrespect” under artistic director Hussain Currimbhoy. The film producer had just been hired four months prior, accompanied by an announcement in which Nelson gushed: “I am confident that with his unique vision, tremendous experience, and remarkable talents, he will successfully steer Hot Docs’ programming team into an exciting new phase.” Currimbhoy planned a “new vision for Hot Docs” that would break down walls. Instead, he appeared to do the opposite. And senior management, according to the 10 programmers who signed the letter, “failed to address overwhelming concerns and early warnings.” According to Nelson’s speech, they had more pressing concerns. “There are times when we have been more concerned with change than making sure that our people are taken care of,” she said at the press conference. “And when you do that, you end up in the situation that we’re in now.”

Instead of supporting the arts, leaders at organizations like Hot Docs increasingly go all in on “exciting” new plans for “incubating” what amount to nothing more than very expensive…vibes. For Hot Docs, that involved spending $4 million purchasing the Bloor Cinema in 2016 and then having to make up the costs of operating a year-round cinema (a challenge even without a pandemic thrown in), followed by leadership carelessly divesting the organization of “small” (see marginalized) films and filmmakers. Other institutions have made similarly extravagant investments. TIFF’s Lightbox and Artscape’s Launchpad (both associated with Toronto’s The Daniels Corporation), for instance, are even more ambitious arts institutions whose sprawling pieces of exorbitant property require massive bank loans and huge cash injections to fund. This puts overwhelming pressure on them to sell out—TIFF rents out its space, Artscape kept developing new ones—while the executives that got them into this mess keep cashing in.

The argument is that CEOs need to make competitive wages; but that never seems to be a priority for anyone else.

A day after the Hot Docs exodus, more than 400 employees at the AGO went on strike, citing the gallery’s failure to increase wages. The president of the union, Paul Ayers, specifically pointed to CEO Stephan Jost, who Ayers said supplemented his $406,000 salary with more than $390,000 in consulting fees from the AGO between 2020 and 2021: “Yet there’s no money for wages?” The argument is that CEOs need to make competitive wages; but that never seems to be a priority for anyone else. And, remember, these are executives in non-profits constantly begging for funding. The first-class travel and cottages in Muskoka start looking conspicuous amidst claims there isn’t enough money to go around.

With the prospect of arts and culture in this city going extinct, and the crumbs thrown by the federal government (a mere $38 million in cultural relief out of a $61.2-billion budget) to gesture at the seriousness of the situation, local media is finally all over this story. It’s so very Canadian to be suddenly interested in covering the arts now that it is in crisis—a crisis that stems, in part, from the media’s historic unwillingness to take it seriously.

My own experience over the past two decades has involved editors, almost all white, telling me that in-depth stories about Canada’s cultural institutions are not newsworthy. The rare people who are allowed to cover culture are of a type. That is to say, their experience often aligns with those they should be confronting. That means their perspective is not generally attuned to the various intersections at play (one white male editor I worked with characterized a marginalized creator’s response to systemic racism as “complaining”). The result is an arts industry that can exploit people and waste resources and escape accountability. Without the kind of evidence that regular reporting provides, those in power can rest assured that accusations of mismanagement may be spun as merely anecdotal. This is why the programmers at Hot Docs wanted transparency, and this is why it was not given—because this boat refuses to be rocked even as it capsizes.

Our Art + Money issue was made possible, in part, through the generous support of Toronto Arts Council. All stories were produced independently by The Local.