On a sunny Saturday morning in May, on the fifth floor of the Dragon City Mall in Toronto’s Chinatown, drag queen Phoenix Black was strutting, navigating between plastic-covered tables and dim sum carts in a sparkly purple leotard and knee-high boots while a medley of Rihanna songs blasted through the speakers.

Since 2022, drag performances have become a regular occurrence at Sky Dragon Dim Sum. A rainbow balloon arch was erected at the entrance of what usually operates as a traditional dim sum restaurant. Gold streamers and a “Queens of Dim Sum” sign were stuck on the wall next to ornaments that read “happiness” and “longevity” in traditional Chinese characters, while circular tables were rearranged to make room for a makeshift stage on the red and yellow carpeted floor.

Over the next two hours, the drag queens lip-synched and danced to Top 40 hits, along with music in Tagalog, Cantonese, and Korean. The music blended with the cheers of restaurant patrons, mostly members of Toronto’s Asian queer community, alongside some older Chinese regulars eating fried squid. Between songs, the performers paused to make jokes about the Asian experience, and express gratitude for being able to perform at culturally specific events that platformed Asian artists.

Next to the makeshift stage, behind a giant siu mai plushie, stood Sum Wong, stage name DJ Sumation.

Wong launched Queens of Dim Sum along with his co-founder Ryan Tran in 2022. It was a twist on the classic drag brunch, created in part because of their frustration with how Asian performers were treated in Toronto’s queer community. When Wong first started DJing on Church St. in the early 2000s, he says he was one of just two Asian DJs in the village. From the outset, it was clear to him that he was getting fewer gigs than his white counterparts. “That’s the way Church street is going,” says Wong. “They usually book more caucasian artists.”

His former stage name, the tongue-in-cheek “DJ SumAsian,” sometimes felt like a too accurate representation of how club promoters saw him—some Asian, one whose very presence on a bill might drive customers away. After a broadcaster misspelled his name as DJ Sumation in an interview, Wong decided to stick with it. Miraculously, he says, he immediately began getting more bookings.

Wong and Tran aren’t the only queer people of colour who have felt themselves nudged out of the Church and Wellesley Village, the Toronto neighbourhood that has historically been an enclave for the LGBTQ+ community. For many queer performers, activists, and event organizers of colour, the Village is not a place they necessarily feel welcome or represented. This sense of exclusion can take many forms, from minor complaints about boring music in clubs, to more damaging forms, like losing out on opportunities to earn a living from performing, or needing to choose between feeling excluded on the basis of race or sexual orientation. It’s left people like Wong with questions about the future of queer Toronto. Does finding a community for queer people of colour mean moving outside of the Village? And what’s lost when community hubs splinter? Amid this uncertainty, many queer Torontonians of colour are carving out spaces that make them feel welcome—navigating a landscape with tensions that feel new, but at the same time, all too familiar.

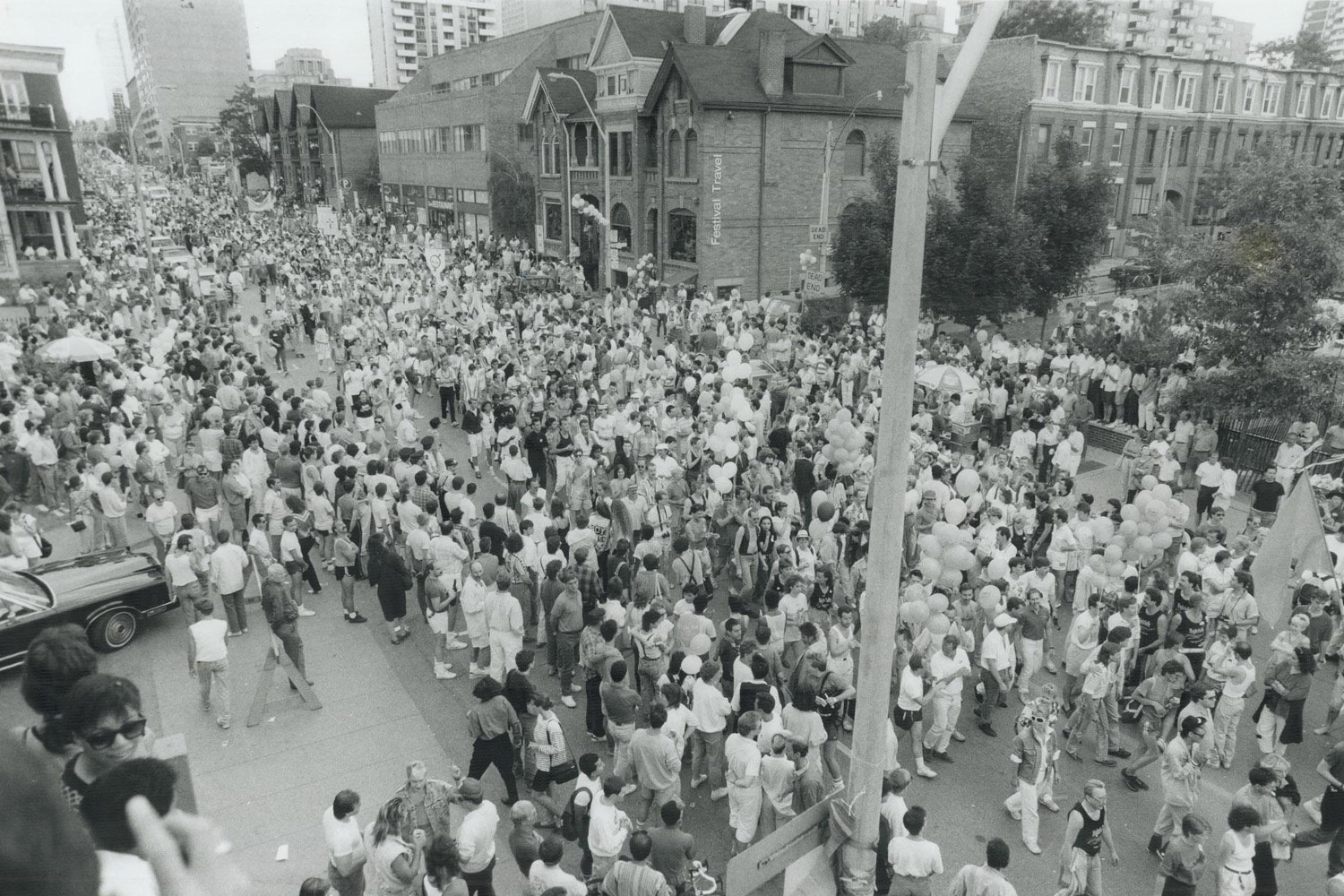

In the early 19th century, when Canada was still a British colony, the tract of land now known as the Village was owned by a Scottish merchant and gay man named Alexander Wood. Over the decades, as the city grew, the area became one of several mixed commercial-residential neighbourhoods in downtown Toronto. By the 1960s and 70s, neighbourhood demographic changes, the presence of affordable housing, and the work of social and political activists pushing for LGBTQ+ rights laid the foundations for the creation of the Village—an enclave for queer people in the midst of a city, and a country, that had largely rejected them.

Today, as you walk south on Church Street from Bloor to Carlton, rainbow crosswalks mark the street. You can see places like the AIDS memorial and The 519—a community centre providing support to the LGBTQ+ community—that are legendary locations in the annals of Canadian queer history. At night, you can hear pop music and crowds cheering from Woody’s and Crews and Tangos, longstanding gay bars that hold frequent drag shows.

In 2005, the Church Street BIA erected a bronze statue of Wood at the corner of Church and Alexander. A white gay merchant who had played only a small part in Canada’s queer history suddenly had his story reframed and shaped by the City of Toronto to become a pioneer enshrined in bronze.

Turning a 19th century white settler into a kind of patron saint of the neighbourhood, and ignoring the messier history of activism and arrests that actually created the haven for queer Torontonians, promoted a specific image of queerness—one that omitted women, and racialized and trans people. In a mishap so fitting it was almost funny, the statue got hastily torn down in 2022 when the BIA discovered that Wood had connections to the residential school system.

The statue episode was emblematic of some of the issues that have long plagued the Village. Many Black queer Torontonians have a complex relationship with the culture of the neighbourhood. In the 1980’s, the centre of activity for much of Toronto’s Black LGBTQ+ organizing was at Dewson House, a home in the west end of the city far from Church and Wellesley. Zami, Canada’s first organization for the Black LGBTQ+ community, was conceived at the kitchen table there. To reach a queer audience, however, it was forced to advertise in white LGBTQ+ magazines, which at times published racist content.

For Jamea Zuberi, the Church and Wellesley neighbourhood has simultaneously been both a refuge and a place she doesn’t quite feel welcome. Growing up in the 90s as a Black lesbian, Zuberi came to the Village often because Jane and Finch, the neighbourhood where she lived, didn’t feel safe for queer people. For her, The 519 was a safe space that hosted inclusive events.

Her relationship with gay bars in the neighbourhood, however, was a different story. And the lack of diversity in the Toronto Pride parade was something that particularly bothered her. The televised parade felt incredibly important to Zuberi—a chance for queer people who lived outside the downtown core to see people who looked like themselves on screen. Back then, Zuberi says, many families in her community held the belief that “being queer was not for Black people.” If representation in the parade could make a difference in a single young person’s life, Zuberi believed, then that was reason enough to push for more representation.

Zuberi co-founded the organization Blackness Yes! which aimed to create a space in the parade for Black queer people. And in 1998, the first Blockorama was held at the Pride festival, inspired by the Caribbean block parties (blockos) that Zuberi experienced growing up. Now, over 20 years later, it’s an all-day dance party that celebrates Black, queer pride.

But according to Zuberi, making Blockorama happen was no easy task. Because the core tenets of Blockorama ran counter to how Pride Toronto operated, she says, “there was tension every step of the way.” Throughout its history, organizers say Blockorama has been moved to smaller and less accessible venues, and has received insufficient funding. These issues made headlines in 2016, when Black Lives Matter Toronto halted the Pride parade and presented a list of demands that asked for more funding, ASL interpretation, and headliner funding for Blockorama. Pride Toronto did not respond to The Local’s requests for comment.

“I think part of why Church street is so white is because white gay men essentially own that space,” says Dainty Smith, a burlesque dancer and founder of a dance troupe for women and femmes of colour, Les Femmes Fatales. “Black queers and queers of colour have never been able to establish a foothold.”

When Smith started performing in the Village, she says there was real resistance to talking about race or politics in performances. Smith often found herself the only person of colour in a group of performers at a venue. “I had found this liberating way to express myself in the world, and I was alone in my liberation,” she says.

Smith recalls hearing white performers ask why people of colour who were occupying these same spaces were being “so political.” “I think back then, a lot of people wanted to put a focus on queerness first, and Blackness and people of colour second,” she says. Creating Les Femmes Fatales in 2010 was a form of resistance to this kind of thinking—a way to platform queer femmes of colour in a way that allowed them to feel empowered in their bodies.

Smith believes that progress has been made in the Village and Toronto’s queer community as a whole, but this increase in representation covers up many issues that queer people of colour still face. “It’s much easier today to think that we do not have an issue in terms of diversity, representation and race. But that’s not true. […] It’s a convenient untruth, that there isn’t any more work to do around racism.”

Les Femmes Fatales’ falling out with Pride Toronto in 2023 illustrates the consequences of this surface-level representation. In early 2023, Pride Toronto named the group the festival’s “BIPOC Ambassador,” and included them in promotional materials. The honour, according to the group, came with the promise of inclusion in media interviews and a spot at the front of the Pride parade. In a June press release, however, they wrote that “these promises largely went unfulfilled. Despite countless efforts to get Pride to make good and to honour the troupe appropriately, Les Femmes Fatales have been ignored by Pride Toronto, shut out from performing on their stages this year as a troupe, repeatedly snubbed and left out of 2023 the Pride Programming.” The group said they were left with no choice but to renounce the honour. Pride Toronto did not respond to requests for comment.

“There is a problem around making any marginalized group so palatable that they’re easy to swallow,” says Smith. “And what the mainstream has done is, essentially, send the message back to us and say ‘If you are well behaved, if you speak well and act well, if you narrow down your sharp edges you can get in.’ And I think that’s what a lot of gay white men did.”

Walk down Church St. in 2024, especially during the last week of June, and you’ll hear the same songs over and over again. “Oh my God, is that Britney?” a market vendor yelled sarcastically during Pride weekend this year when “Toxic” came on for what felt like the tenth time that day.

According to Queens of Dim Sum co-founder Sum Wong, the sameness of the music is a reflection of Church street’s diversity problem. He says the venues in the Village that he performs at tell him and other drag queens that they need to perform “commercial songs that everybody knows.” Wong even alleges that Asian drag queens are having issues getting called back for gigs if they perform songs from their culture.

Wong blames RuPaul’s Drag Race for this conservative approach to music. Once a niche reality competition on the queer-focused network Logo, the show has become a mainstream hit and the first exposure that many straight people have to drag culture. “We have a lot more straight people who come down to see drag shows,” says Wong. The songs featured on the show, however, are all in English and are mostly commercially successful pop songs. Because of this, the venues in the Village start sticking to the same list of pop songs that get featured on Drag Race and “mainstream” queer culture.

The consequences of playing the same music go beyond just a boring setlist during a night out. By only giving visibility to white artists, and catering mainly to the interests of white patrons, the Village confines its display of queerness to a single type, and risks pushing everyone else out.

Jamea Zuberi of Blockorama, who is now a school principal in Toronto, says she doesn’t spend much time at clubs in the Village. She doesn’t feel welcome in venues on Church Street. Instead, Zuberi and many other Caribbean queer people frequent spaces that reflect their cultural identity, such as the city’s various mas bands—the costumed groups that “play mas,” or masquerade, during carnival. In these spaces, however, Zuberi says queer people can often face disrespect and ridicule. Last year, she was a part of a group that challenged the homophobia of many of these mas bands. She remembers receiving a phone call about an incident at one of the mas camps she frequented, in which some attendees physically intimidated a gender nonconforming woman and misgendered her. Zuberi and many others thus face an impossible decision: choose to feel excluded on the basis of race, or on the basis of sexuality.

Zuberi’s experiences in the carnival scene make it clear that, until we get a whole lot more tolerant, Toronto still needs LGBTQ+ enclaves like the Village. Hopefully it’s a Village where different groups of queer people see themselves represented. In the face of systemic racism, however, queer people of colour are finding and creating spaces in Toronto more welcoming to their identities.

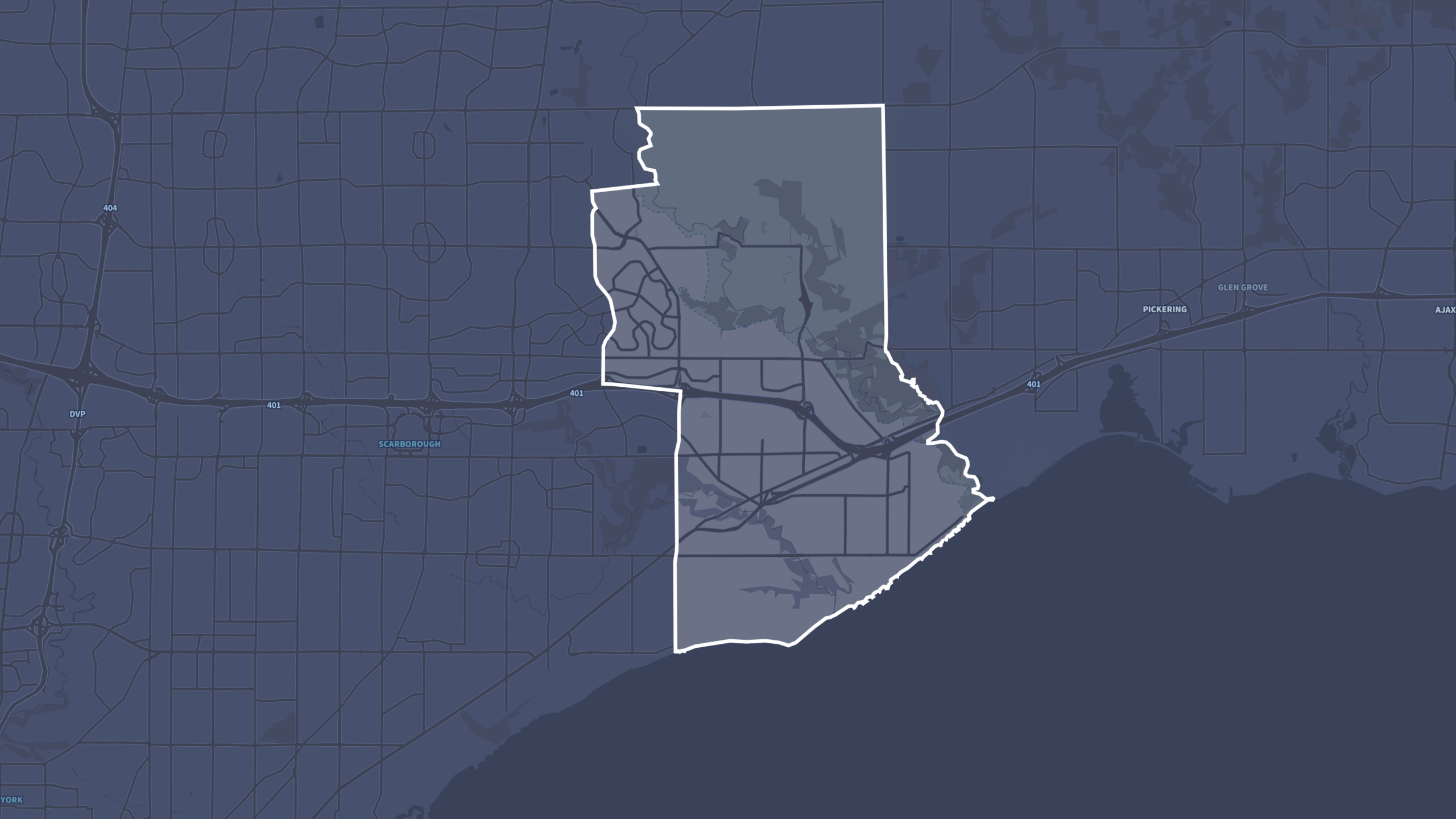

In 2023, Pride Toronto brought its festivities to Scarborough, Etobicoke, and the Jane and Finch neighbourhood—areas that were historically not always welcoming. Zuberi made it a point to attend Jane and Finch Pride because an event like that would have been unheard of when she was a kid. She turned up at the parking lot of the Jane Finch Mall initially cautious, and ready to support the event should there be backlash from the wider community, but there were no incidents. Zuberi felt elated. “I guess I showed up as my young self,” she recalls. “A part of me thought, ‘This is what we worked towards. This is what we worked so hard to get.’”

For Wong and Tran, putting on a drag show in a Chinatown dim sum restaurant is a way of carving out a space that is welcoming to them in the face of a queer establishment that makes them feel excluded. Holding the performance in Chinatown means that Sky Dragon’s regular clientele, middle-aged and older residents of Chinatown, see the performances. Growing up, Tran often felt like the concept of being queer and coming out were seen as “only a western thing” because of how little representation Asians, let alone queer Asians, got in the media. Now he sees how members of the Asian queer community bring their family members to the show, as a way to introduce them to queer culture. “It would usually be that generation’s first time seeing drag,” he says. “Because dim sum is so familiar, it makes it easier to kind of build this bridge between drag and queerness in a familiar, safe environment.”

Wong and Tran both remember the first Queens of Dim Sum vividly. That same rainbow balloon arch was at the entrance of Sky Dragon, but the performance space only spanned the thin strip of carpet against the restaurant wall. The three drag queens performing that day were all crammed into the single tiny changing room usually used by brides.

Wong and Tran didn’t explicitly tell the owner of Sky Dragon that they were putting on a drag show, simply describing it as a performance with music and dancing. When the show started, the servers who pushed around dim sum carts were so stunned that they stopped in their tracks, their surprise only heightened when a drag queen tried to interact by falling into the splits in front of them. When the chefs caught wind of what was going on, they ran out of the kitchen whenever they could spare a moment to witness the performance, and ran back in to tend to their food. Pretty soon, when the servers had worked through their initial shock, they started clapping along and cheering on the performers.

When the event ended, the owner of Sky Dragon approached Tran and Wong. He had a specific demand: “When are you doing the next one?”