To lay the bricks for a three-story custom home in, say, Etobicoke, you need six months, 15,000 bricks, and four sets of hands. Today, finding those hands is harder than it’s ever been.

Twelve years ago, when Brendan Playfair founded Johnson Playfair Inc., a Leaside brick and stonemasonry contracting company that builds high-end custom homes across the GTA, his job postings would be met with applications from highly skilled workers aged 50 plus, with decades of experience in the field. Today, many of those craftsmen have retired, aged out of a gruelling line of work that demands hours under the hot sun or outside in sub-zero temperatures, lugging bricks and perpetually washing mortar off of dry, cracked hands. Instead, when Playfair now puts out a call for workers, he’s hearing from recent immigrants and temporary residents. To get a qualified craftsman, he’s even paid the thousands of dollars required to bring someone into the country as a temporary foreign worker.

Canada’s construction industry is facing a massive shortage of workers, with tens of thousands of roles unfilled across the country. This labour gap has a domino effect that cascades all the way down to homeowners and renters. “When any particular trade responsibility is held up or slowed down because of lack of staff, it will also delay every trade that is to come after them,” says Playfair. “Every trade follows on the work of another.” When there aren’t enough bricklayers or stonemasons to finish a project on time, it delays the window finishers, the roofers, the painters, the landscapers. Heating costs, equipment rental, and labour hours pile up, leaving homeowners to foot a hefty bill.

Join the thousands of Torontonians who've signed up for our free newsletter and get award-winning local journalism delivered to your inbox.

"*" indicates required fields

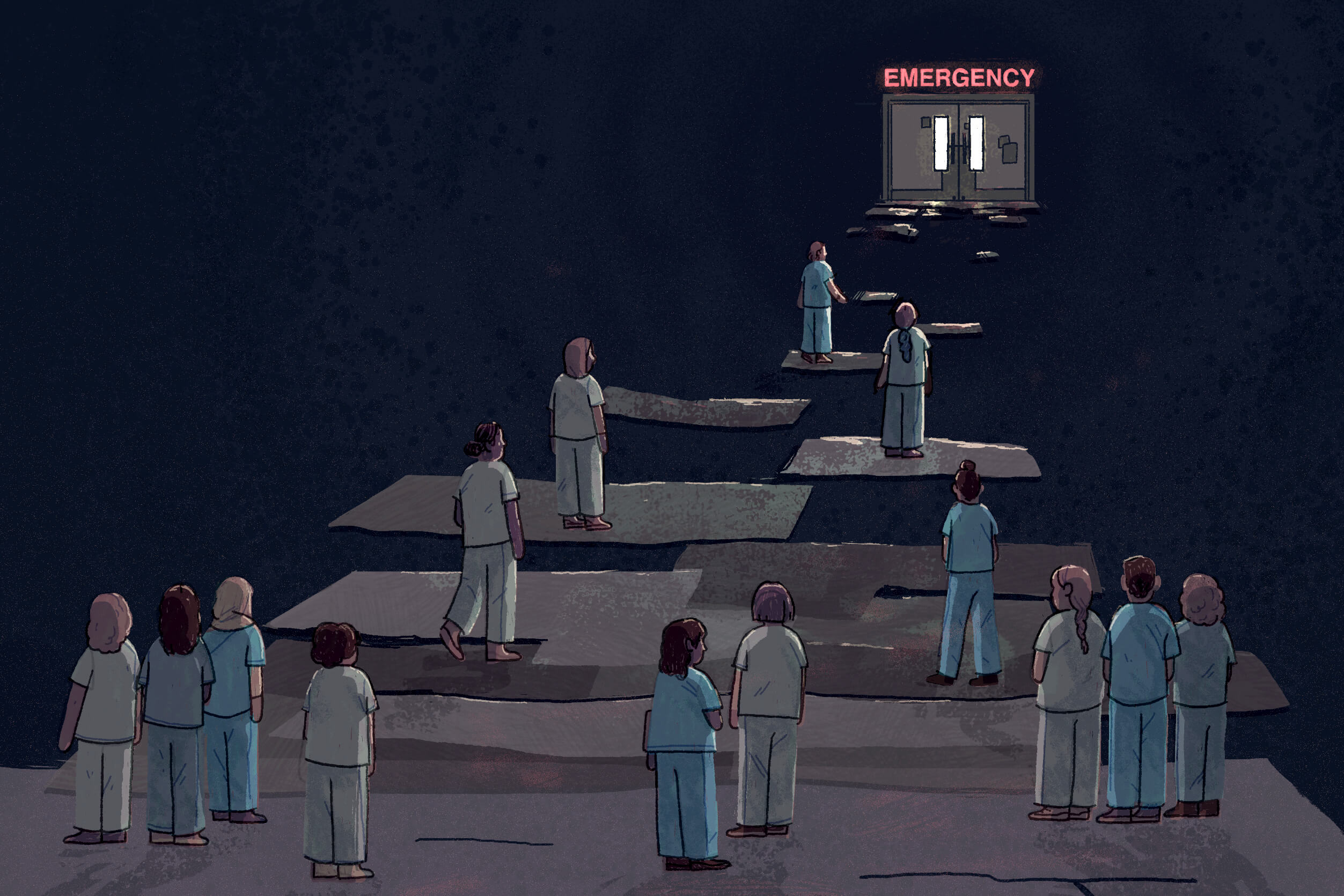

Canada has a rapidly aging workforce across every sector, with the worker to retiree ratio going from seven to one in 1975 to a predicted two to one by 2035. In Ontario’s construction sector, 100,000 people are expected to retire in the next decade, exacerbating the existing worker shortage and contributing to low housing stock and unaffordability. For years, the government (and financial experts, academics, and members of the construction industry) have understood immigration to be a key solution to the housing crisis. Immigrants, they recognized, were essential at every stage, from demolishing bungalows in North York to make way for multi-family dwellings, to installing roofing on new housing developments in Mississauga, to welding rebar for condos in downtown Toronto. Then, public sentiment on immigration began to shift.

In October of last year, with months of public polling indicating a sharp decline in public approval of immigration, Prime Minister Justin Trudeau and Minister of Immigration Marc Miller announced a 20 percent reduction in the number of permanent residents permitted into the country for three years going forward. Temporary residents were also set to drop to less than five percent of the population.

In their announcement, Miller and Trudeau named housing as one of the primary justifications for the policy change. This reduction in immigrants, they said, would allow the government time to “make the necessary investments” in housing, to ease demand for housing by 670,000 units by the end of 2027. The rationale dominated headlines in the days that followed, affirming a narrative that had taken root across the country in the year prior: the key to reducing housing shortages and improving affordability is curbing immigration. The policy seemed to draw a straight line between fewer newcomers and a better standard of living for everyone else.

What it failed to acknowledge was the construction sector’s growing reliance on immigrants and temporary workers to replenish a flagging workforce—workers who are also disproportionately likely to face precarious, underpaid, non-unionized working conditions. While public discourse has left immigrants to bear outsized responsibility for today’s housing unaffordability, the fine-print conditions of the new immigration policy continue to capitalize on the labour potential of temporary residents to build houses for Canadians, while leaving them fewer pathways to secure a lasting future in the country.

The prevailing narrative today is that immigrants are driving up housing prices because they’re taking up housing stock. The truth is not that simple.

“Immigrants tend to be the scapegoat on the demand side…especially because they’re often visible minorities,” says Morley Gunderson, professor at the University of Toronto’s Centre for Industrial Relations & Human Resources.

Yes, an increase in immigration inevitably means more demand for housing. But the country could absorb this demand if its major cities weren’t plagued by systemic challenges and delays to housing development. In a research paper last fall, Gunderson and his co-author argued that beyond immigration, unaffordability is exacerbated by factors like the financialization of the housing market, a dearth of affordable and social housing, extended timelines for housing development due to regulation and planning-related bureaucracy, spikes and troughs in interest rates and financing, NIMBYism, and a stagnant, under-equipped construction sector still grappling with the aftermath of COVID-era disruptions.

Additional research has shown that the country’s rental housing stock is being financialized—turned into a means of profit for shareholders—at a rate far greater than it’s being developed. While the luxury condo market has boomed, affordable housing development has stagnated since the ‘90s. And any existing residential development is riddled with months of delays, costing homeowners thousands.

With so many systemic obstacles to housing availability and affordability in this country, “a lot of the backlash [against immigrants] is very short sighted,” co-author and Toronto Metropolitan University professor Wendy Cukier warns. “And my worry is that once you let the genie out of the bottle where you blame immigrants for everything that ails you, it’s very hard to get it back in.”

While critics of immigration blame newcomers for the housing crisis, the construction sector is actually growing increasingly reliant on those same newcomers to make up for a flagging labour force. Census data compiled for The Local by the Institute for Work and Health (IWH) reveals that the number of immigrants in the construction industry who have been in Canada for less than five years has gone up nationally by more than 220 percent between 2001 and 2021, and nearly 150 percent across Ontario. By contrast, the number of native-born Canadians working in the industry rose much less dramatically. In Toronto, there are now more immigrants and temporary residents in the construction sector than non-immigrants.

Temporary residents—including temporary foreign workers, students, those holding short-term work or mobility visas—have grown at a faster pace than any other demographic in the construction sector. Nationwide, there’s been a nearly tenfold increase in temporary residents in construction in the last two decades, from 3,000 in 2001 to nearly 30,000 in 2021. Last year, the CBC found that permits for temporary foreign workers under the “construction trades helpers and labourers” category grew by 4,000 percent between 2018 and 2023, the third-highest rise across 15 job types, behind only health care aides and food service workers.

The federal government clearly recognizes the construction sector’s dependence on temporary workers. Despite announcing a plan to reduce temporary foreign workers to less than five percent of the national population (they were 6.8 percent as of last summer), the Liberals have specified that construction workers, along with labourers in agriculture, food service, and health care, would be exempt from the reduction. These workers are then left to support the sector in a climate that is both increasingly hostile to them and less likely to grant them any permanent road to residence.

Temporary workers in the construction sector also face the most precarious working conditions. IWH data shows they are more likely to be in temporary employment, and more than seven times more likely to be low-income than non-immigrants. The temporary foreign worker program itself has been described as “a breeding ground for contemporary forms of slavery” by a UN special rapporteur. And the proliferation of temporary work, gigs, and day labour in the construction sector leaves the door open to exploitative conditions for undocumented workers, either those who entered the country and the workforce without authorization or those who began as temporary residents and just kept working after their permits expired.

44-year-old Edgar Mendosa (who is using a pseudonym to protect his identity) came to Canada from Mexico in 2019 to make money for his daughters and grandchildren, and has spent four years in the GTA construction sector as an undocumented subcontractor on short contracts. He’s worked on framing, roofing, and mainly demolition, tearing down residential and commercial structures slated for renovation and rebuilding. There’s a tight-knit community of undocumented Mexican workers in the city, Mendosa tells me. Every morning, he’d take an hour-long TTC ride from North York to a pick-up spot, then be driven to a construction site with other men in the same position as him, where he’d work sometimes until 7 or 8 in the evening. At the end of the week, he’d be paid in cash. But last spring, Mendosa was injured on the job, a knee injury that left him hospitalized for three days, bedridden for the three months that followed, and $14,000 in debt to the hospital due to his medical procedures.

Male new immigrants tend to face twice the risk of workplace injury as their non-immigrant counterparts, explains Peter Smith, president and senior scientist at the IWH. On top of this, “when jobs are temporary, or there’s a lot of turnover, sometimes safety procedures cannot be adhered to.” Unfamiliarity—when it comes to employers with their employees, and employees with their jobs—can lead to poor communication, failed safety training and procedures, a lack of trust, and the absence of a security net in the event of a safety incident. “We do know that the risk of injury is highest within your first six months on the job,” Smith adds. Being a gig worker or day labourer can sometimes feel like experiencing your first six months over and over and over again.

“These are jobs that Canadians don’t want to do. So we do the dirty jobs, right?”

In the days following his injury, Mendosa’s boss was furious that he’d sought care at the hospital given his undocumented, uninsured status. “He abandoned me,” Mendosa says with the aid of a translator. “I was left without being able to pay for the hospital stay, and besides that, I couldn’t walk. I couldn’t walk, and I couldn’t work.”

His capacity to work never fully recovered. “If before I could do my activities at 100 percent, now it’s 50 percent,” he says. He spent the better part of last year attempting to get workplace injury insurance through the Workplace Safety and Insurance Board, with the help of the Industrial Accident Victims’ Group of Ontario legal clinic, to pay back the debts from his hospital stay. So far, he’s been unsuccessful. Without amnesty for his undocumented status, he cannot return home. He’s still working to send money home to his family.

When I ask Mendosa for his perspective on the national double bind of reducing immigration but relying on immigrant labour, he seems resigned. “These are jobs that Canadians don’t want to do. So we do the dirty jobs, right? It’s us who support the construction field. They just hire us, and then they wash their hands.”

If the Canadian construction industry continues to lean on temporary residents to fill gaps in the construction sector, while closing doors to permanent immigrants, opportunities for exploitation will run rampant. “And as long as they pay us, and as long as we can support our families,” Mendosa admits, “we have to do that kind of job.”

As recently as 2023, the Canadian government recognized immigrants as key to the country’s labour shortages. So when construction industry leaders like Nadia Todorova heard the announcement about cuts to immigration, and its housing-related rationale, they felt it upset an already delicate balance.

Todorova, executive director of the Residential and Civil Construction Alliance of Ontario (RCCAO), hadn’t heard about any policy consultation between the federal and provincial governments and the construction sector in charge of building the very housing stock Marc Miller referenced in his announcement.

“The average age of a skilled trade worker is north of 40, and in some trades, is north of 50. So that demographic trend is really a ticking time bomb,” Todorova says. With continued demand for new infrastructure, “the challenges are only going to get that much more intense…that’s why we were a little bit unhappy, I would say, with the federal policy reducing [immigration] targets.”

It may be a cliché to say that immigrants built this country, but every expert The Local spoke to says it anyway.

“It’s literally our history,” says Andrew Pariser, vice-president at RESCON, an association representing Ontario housing builders.

For most of the 20th century, he says, Italian immigrants, Portuguese, Irish, people of Jewish descent, or from almost any country in Eastern Europe you can name, have all had a hand in this province’s construction sector.

When Canada introduced a points-based immigration system in the 1960s, prioritizing immigrants with higher education or particular economic traits over skilled trades, it reshaped the construction industry, reducing the steady flow of immigrants who had entered the construction sector for the hundred years prior. Simultaneously, changing perceptions of the trades here in Canada meant that fewer young people were going into the field. But provincial programs like the Ontario Immigrant Nominee Program, designed to take in immigrants whose skills fill a gap in the provincial labour force, have in recent years brought new life to the construction sector.

The sudden policy announcement in October “felt to me like a knee-jerk reaction that was driven by politics,” says Pariser, who also reported not hearing of any consultation before the policy was announced. “So much progress was being made, and now it’s all been taken away.”

“Every number on a page is a person…Whatever [the government] does now, we’re going to be paying for it for the next 10 years.”

Reducing immigration, of course, isn’t a simple matter of turning off a tap. There are enormous knock-on effects. In the U.S., farmers warn that mass deportations could cripple the dairy industry, not only drastically increasing the price of milk but causing devastation to cow herds from lack of workers to milk and take care of them. Immigration crackdowns in the state of Georgia have left millions of dollars of produce rotting in the fields. Nothing so radical is expected, yet, from Canadian policy shifts. But one area that is likely to be hit is the country’s tax revenues. RBC predicts the incoming drop in immigration rates will lead to a federal budgetary shortfall of $50 billion over the next five years, and that is just an early prediction.

Construction industry leaders and workers now anxiously await details of how the Liberals’ immigration targets will affect two of the major pathways through which workers enter and remain in the country. One is a pathway available to each province to accept immigrants working in fields vital to their local economy. (In Ontario, this is the Ontario Immigrant Nominee Program.) Following the 20 percent reduction in federal immigration, Miller has also reduced most provincial immigration quotas by 50 percent, which provincial leaders say poses a massive threat to their economy and labour force. The second program is for out-of-status construction workers: a small, 1,000-spot amnesty initiative introduced in 2019 to grant permanent residency to GTA construction workers with lapsed work permits. Both programs were heralded as successes by the construction sector. Now, that is under threat, with no clear indication of how many construction workers will be brought into the country in the reduced immigration stream.

In a statement to The Local, Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada spokesperson Jeffrey MacDonald wrote, “It’s important to note that the housing crisis was not caused by immigration.”

“While higher immigration numbers were essential to our economic success and growth, pressures on housing, infrastructure and social services now require a more comprehensive approach to welcoming newcomers,” MacDonald wrote. “It is also clear that Canadians want the federal government to more tightly manage the immigration system.”

He added that changes to the federal immigration plan for 2025 will allow for greater consideration of the country’s labour needs, including the skilled trades.

“Immigration is a unique issue, because it involves people’s lives,” says Pariser. “Every number on a page is a person…Whatever [the government] does now, we’re going to be paying for it for the next 10 years.”

Ultimately, if we want to reform immigration policy while meeting Canada’s drastic housing development needs, scholars, advocates, and industry experts alike tell me, the answer lies in the points system. The points system, which gives priority to immigrants based on factors like age, higher education, work experience, and language skills, was a vital part of universalizing and regulating Canadian immigration policy, eliminating restrictions which until then had favoured white immigrants over racialized ones. But it’s also “a lingering manifestation of class bias,” says Myer Siemiatycki, professor at the TMU department of politics and public administration.

He and others argue that the system awards too few points for trades skills and physical labour, instead prioritizing PhDs and Masters degrees. It was only in 2023 that the federal government began recognizing construction trades as a category in its Express Entry program to select permanent residents; in the two years since, 6,100 permanent residents have been selected across all skilled trades. “We just presume, ‘Oh yeah, give me a university grad, rather than someone who’s a bricklayer,’” adds Siemiatycki.

This needs to change, he says: Canada needs tradespeople at least as much as they need us.

Now, Siemiatycki points out, thousands of temporary residents working in trades in Canada will be passed over for permanent residency and will be forced to go back to their countries of origin at the end of their work permits, despite holding skills that the country desperately needs, and despite having set down roots and created homes here. “I think it’s really a lost opportunity.”

__

The Immigration Issue was made possible through the generous support of the WES Mariam Assefa Fund. All stories were produced independently by The Local.