The 19 towers of St. James Town jut out in stark contrast to the Cabbagetown and Rosedale houses surrounding them. Seemingly haphazardly placed, with patches of grass and walkways between them, the buildings were designed to attract young professionals eager to live and work downtown. Today, the city block contained by Sherbourne, Parliament, Bloor, and Wellesley streets is the most densely populated in Canada — officially home to around 18,000 people, though local community organizations estimate the actual number is double that.

On a rainy day in April, the Immigrant Women’s Health Centre mobile clinic pulls into the main lot of the high-rise complex, parking in front of a mini plaza with an Ethiopian spice market and a shop called Philippine Variety. Inside the 31-foot Winnebago, the team gets straight to work, pulling lube and gloves out of cupboards and arranging plastic baskets of laboratory forms and sterile containers. More than twenty women have appointments for pap tests (or cervical cancer screening tests), Sexually Transmitted Infection tests, pregnancy tests, and birth control counselling.

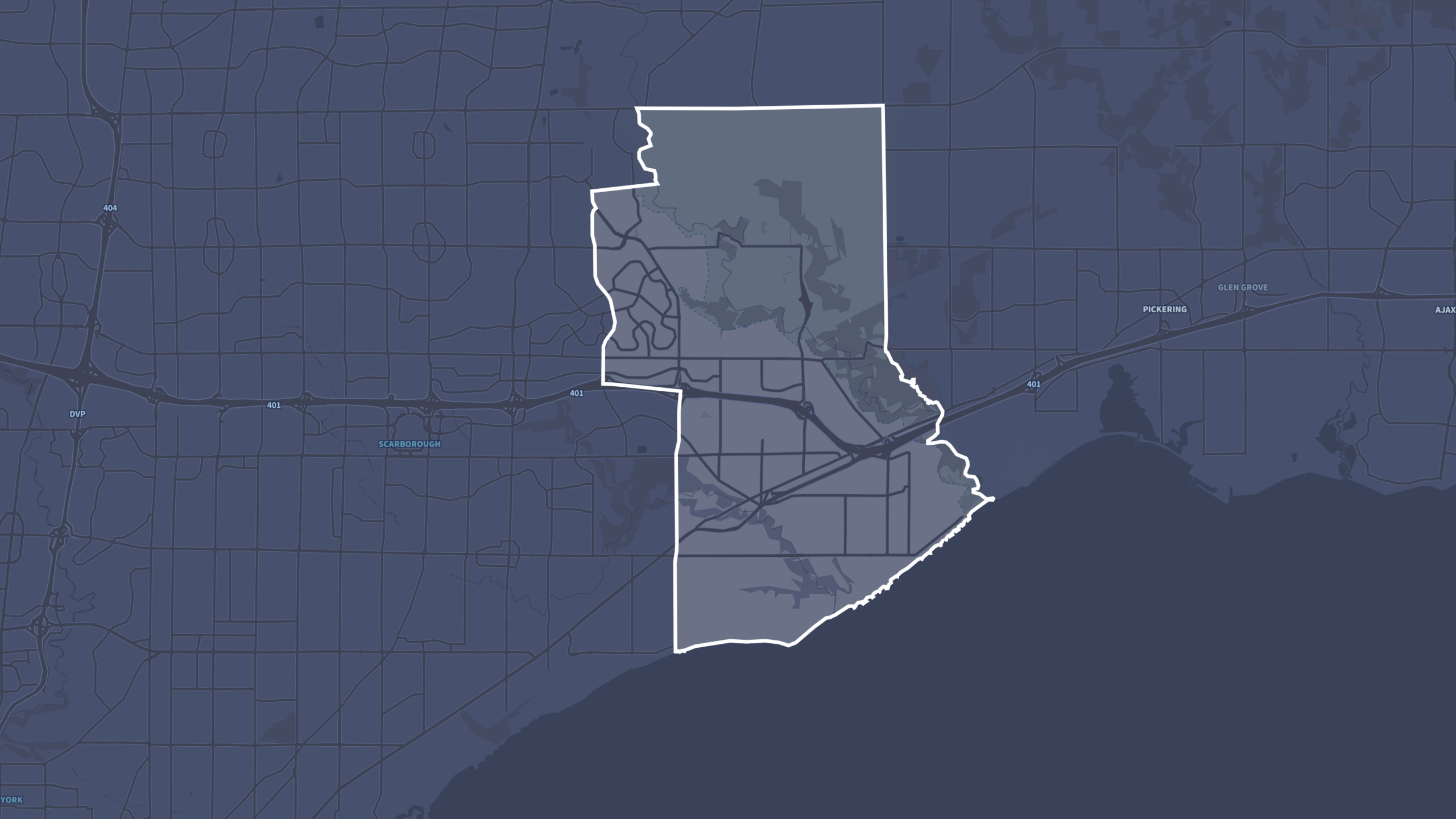

The mobile clinic was launched by Toronto Public Health in 1980 to reach immigrant women working in downtown garment factories who weren’t making routine family doctor appointments. Today, the Winnebago goes out most Tuesdays and Thursdays to community centres and adult learning centres throughout the Greater Toronto Area. An 18-year-old ‘bus,’ as clinicians call it, might not seem like the ideal place for a sexual and reproductive health appointment. But for women struggling to pay bills and look after children, the convenience is vital. It helps that the clinic provides care that isn’t always found in walk-ins or family doctors’ offices, including non-judgemental counselling, translation, and free care regardless of whether patients have an Ontario’s public health insurance plan (OHIP) card. About half of the clinic’s patients don’t have health insurance, most often because of the three-month waiting period before newcomers are eligible for coverage. “Our demand is so high,” says the clinic’s nurse. They’d go out more, if they could.

Wearing a toque and a puffer vest, the clinic’s coordinator, Anna Cioffi, is a powerful force — the literal and figurative driver of the whole operation. An Italian-Canadian who moved here with her family when she was nine, Cioffi remembers translating and advocating for her working-class parents at health-care appointments. She’s been working at the immigrant women’s clinic for almost three decades — forging connections with community leaders, hiring doctors and counsellors, reassuring nervous patients and motivating her team, who often don’t eat lunch until dinnertime on mobile clinic days.

There’s a knock on the door and Surabhi Khare steps in, pulling down the hood of her jacket. She’s the project coordinator of the Healthy Living programs at Community Matters Toronto, a St. James Town community organization that runs health programming, from diabetes counselling to Zumba classes. The mobile clinic always partners with a local organization. People like Khare promote the clinic, sign up patients, and reassure those who may be hesitant.

Khare shows Cioffi where to park.

“Hang on everybody, we have to move,” Cioffi says, turning on the engine.

“What shall we hang on to?” jokes Sharisa Mohamed, a health counsellor, who is sitting in the passenger seat.

On the back wall is a labelled diagram of the female reproductive system, one of three hung up in the clinic. Mohamed uses the diagram to discuss pregnancy, STIs, birth control, and the reproductive system — a sex-ed crash course for the women most in need of the information. Research shows that immigrants are more likely to have an unintended pregnancy than those born in Canada, and women who have been in the country for less than 10 years are less likely to be up-to-date on cervical cancer screening. Screening rates drop even further for low-income women and those over 50. A 2010 study found that women who met all three of the risk factors had a screening rate of 31 percent, compared to 71 percent for the rest of the population. In North St. James Town, just 42 percent of adult women had a pap smear between 2012 and 2015, the third lowest rate among all 72 neighbourhoods covered by the Toronto Central Local Health Integration Network. “With preventative care, like pap smears, you’re catching stuff early on, which means the system is spending less later on,” explains Dr. Sonika Kainth, the mobile clinic’s physician. “You avoid a patient having to undergo chemo and radiation.”

After countless visits to communities across the GTA, the clinic’s team has a set routine, and manage to operate smoothly in tight quarters. Patients first spend anywhere from two to fifteen minutes in the closed-door counselling room. Mohamed sits in the passenger seat of the Winnebago, which swivels to face a table. The patient sits on the other side, looking out the Winnebago’s windshield. Mohamed asks each patient about her sexual history, if she’s had a pap, and if her periods are regular. If English is a barrier, a translator is provided by the community partner organization. For many women, it’s their first time discussing their sexual health with a health professional. Often, Mohamed will call a patient back the next day to discuss lingering concerns.

After speaking with Mohamed, the patient moves to the examining room, where Kainth goes over some of the main points made by Mohamed and conducts tests with the patient’s consent, explaining each step. It’s not uncommon for women to hug the staff, or to pass on messages of their gratitude.

While Kainth gets ready for her first patient, Surabhi Khare is back at a common room in one of the high-rise buildings, where Community Health Matters is hosting a health fair. As a woman makes Moroccan pancakes on an electric griddle, Khare sits down with 36-year-old Kavita, an Indian woman wearing a long cotton kurta, and fills out her intake form. Kavita has been living in Canada for eight months. She came here from India with her husband, toddler, and eight-year-old to work in the IT sector. She’s never had a pap test before. It costs money in India, and since she’s been here, she hasn’t been able to find the half day it will take, with travel and wait times. But when she heard it was being offered on-site, she signed up. “It’s just a safety precaution,” she says.

Next is Cathy, who works two jobs and looks after her son. “It’s hard for me to find time to make an appointment for my doctor for this,” she says. It’s been seven years since she last had a pap test, which the Society of Obstetricians recommends patients get every three years.

Niru has been to the mobile clinic before and prefers it to her doctor’s office. “There is no waiting time,” she says. “My family doctor has a long queue, at least one hour.” But Niru is not complaining. She loves the community. “The parenting centre, the school, everything is a reachable, walkable distance. I’m very happy here,” she says.

Newcomers like Niru are taking advantage of the downtown lifestyle that urban planners wanted to encourage when they tore down blocks of Victorian houses to make way for the massive residential high rises. But the young, childless urban professionals developers hoped to attract were never interested in the gray, now noticeably aging towers. Today, most households in St. James Town have children and almost 60 percent of the residents speak English as a second language. Around a third live below the poverty line. Community groups have filled in the service gaps with after-school programming for kids, and health programming for all ages, including seniors.

‘Neighbours helping neighbours’ is the motto of Community Matters. Before the mobile clinic, Khare explains, the resident volunteers spread word through neighbour and friend networks. When a woman was hesitant about having the pap test, a volunteer showed her a YouTube video so she could see it wasn’t that scary. Bhoomi, a St. James Town resident, explains that many of the local women “stick to their community,” relying on those who have already successfully navigated the bewildering labyrinth of bureaucracy in their new country. A woman might not trust the bubbly public health representative they’ve never seen before. “But if a friend will tell her in her own language why something is important, she’ll be convinced,” says Bhoomi. And sometimes, it does take some convincing. Some women will say, “I have to take permission from my husband,” Bhoomi explains.

“The common theme among all of the different communities and neighbourhoods we go to, is a lack of empowerment,” says Kainth. Community partners start the conversations about sexual and reproductive health, and the clinic’s staff pick up from there. When Kainth and Mohamed recommend condoms, they often hear, “What if the man doesn’t want to?” A line that Kainth and Mohamed repeat often: It’s your body.

On the concrete side of a parking garage entrance in St. James Town, you’ll find an 80-foot-long mural divided into three panels. The first honours the Indigenous peoples who lived on this same land. The middle panel pays homage to early settlers fleeing the Irish famine. The final scene represents the newcomers to St. James Town, who largely hail from South Asia. There is an adorned elephant, a blooming lotus, and in the middle, a strutting peacock with the sun and the moon in its feathers. Peacocks normally fly a few feet, explains local artist Poonam Sharma. This one flew thousands of miles to live here, between two time zones, amid many worlds.

Studies show that immigrants’ health deteriorates in the first five years in their new country, due to diet and lifestyle changes, as well as the pressures of adapting. That’s especially true for immigrant women, who have worse mental health than Canadian-born women. “It’s the daily stress,” says Khare. She explains that many of the women in her community are highly educated in their home countries, but they’re frustrated that their credentials aren’t recognized here. “It’s hard to understand the system, the education system, the health system, the language,” she says. “They really want to chitchat with their brothers and sisters and their parents and they cannot call because it’s night time there. They miss that immediate connection.”

In a new world that is isolating and confusing and damn cold, even on this supposedly spring day, what many low-income, immigrant women need is for people to ease the burden. They need people to come to them, to reassure them, to be a source of real human connection and comfort. Every so often, that comfort comes from an all-women team who pull up to their apartment building with a Winnebago that’s decked out in uterus diagrams.