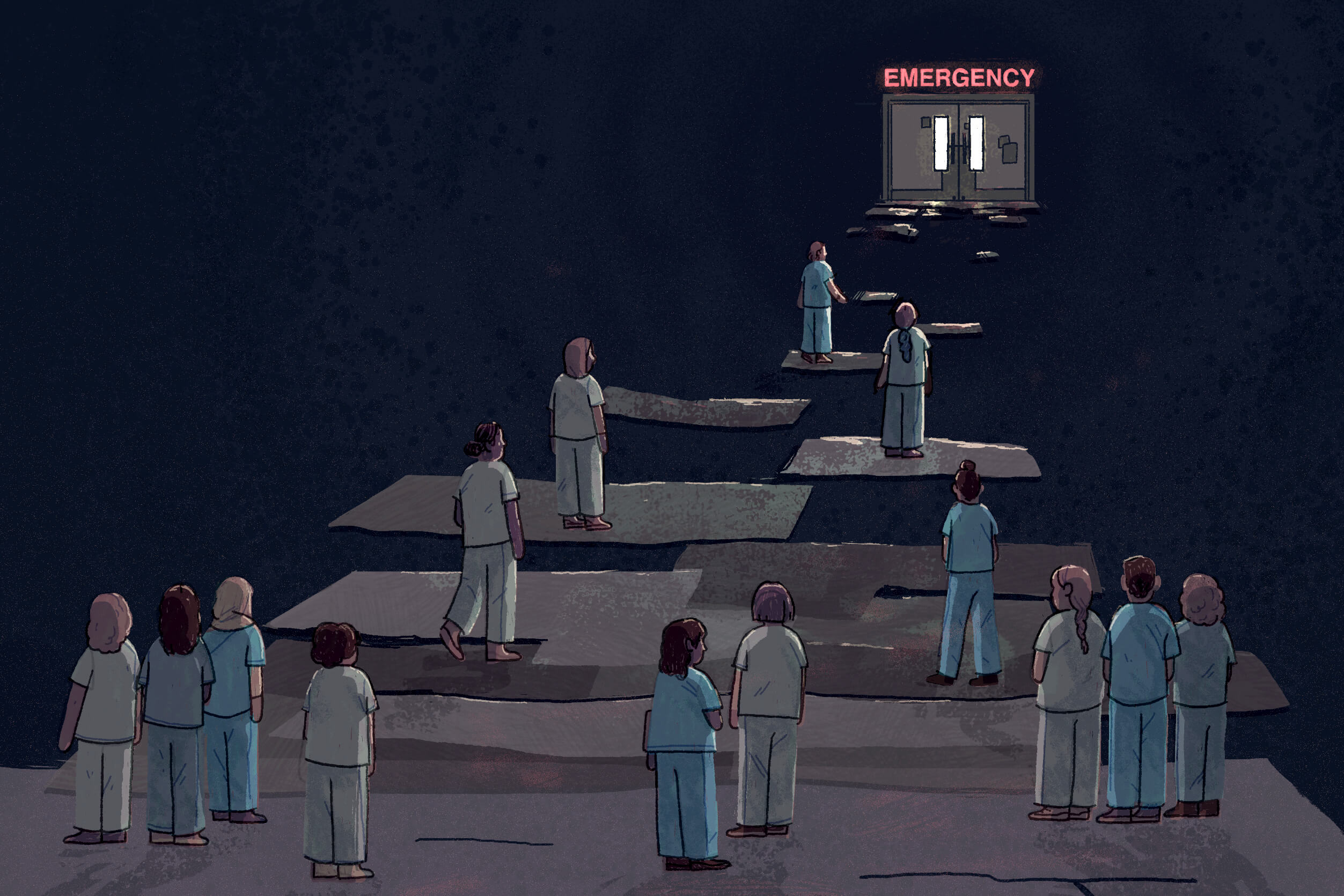

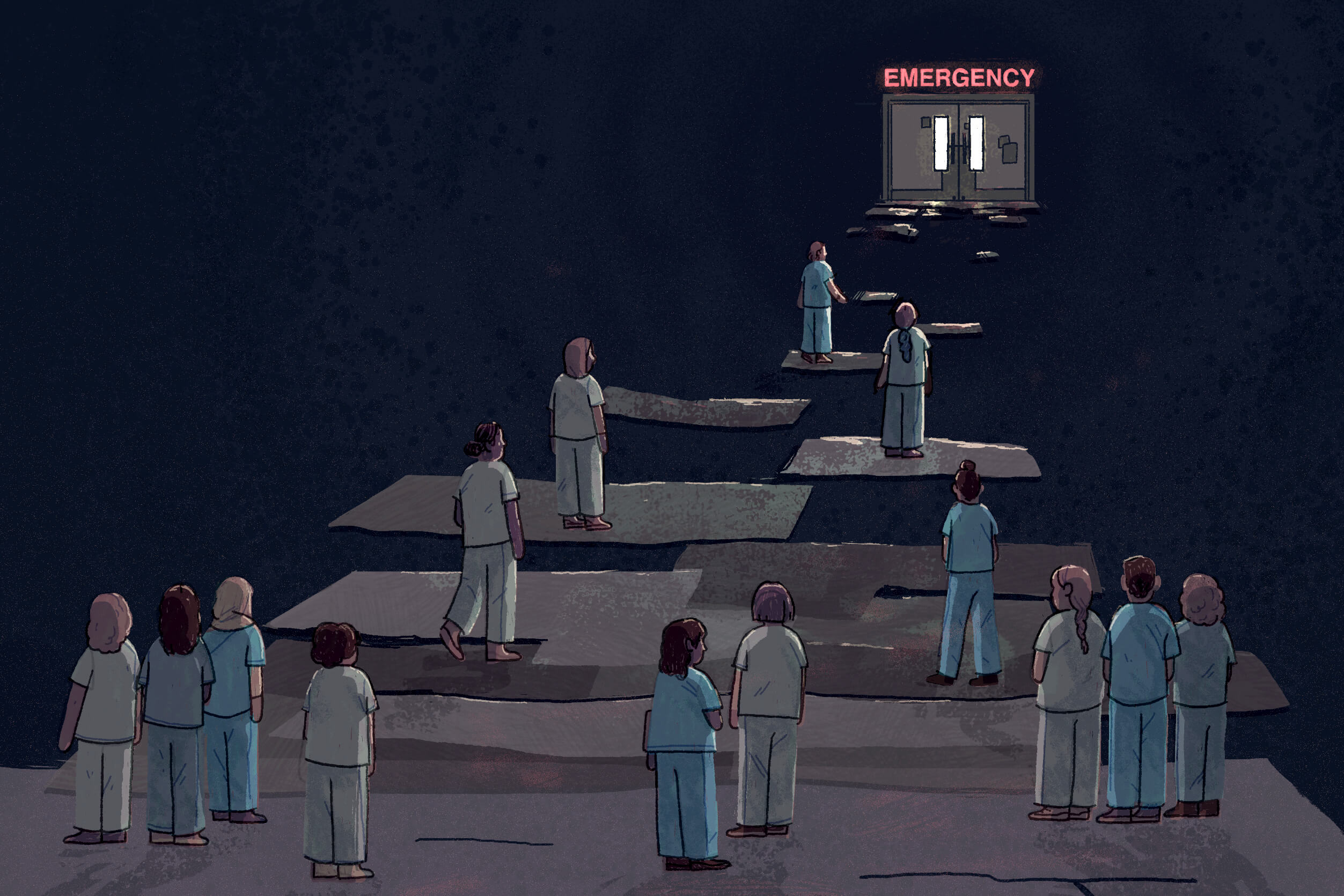

In the summer of 2022, more than two years into the pandemic, staffing shortages at hospitals in Ontario, and across the country, had reached dangerous levels. Exhausted and overworked nurses were at their breaking point. Many were falling sick. Others were calling it quits. In communities like Perth, Clinton, and Listowel, understaffed hospitals were forced to close their emergency departments for hours or even days. Patients at Toronto hospitals languished in crowded emergency waiting rooms. Some waited 20 hours or more before being admitted.

That summer in Toronto, Junarose Guerrero was on tenterhooks. Her Canadian work permit had run out the previous year, and despite having applied for an extension before it expired, she was still waiting for a reply from the IRCC, or Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada. Guerrero had come to Toronto in 2019 as a home support worker, or caregiver. But since she was an experienced nurse, trained in her home country of the Philippines, she intended to eventually put her nursing skills to work here.

Guerrero, who has bright eyes and an easy laugh, had spent more than a decade working in hospitals. Tasks like administering injections, taking patients’ vitals, and suturing wounds were as routine for her as tying her shoes or brushing her teeth. She had graduated from a rigorous four-year bachelor program in nursing in the Philippines, then moved to Saudi Arabia in 2011 for a hospital job, leaving behind a young daughter and fiancé. There, at the southwestern tip of Saudi Arabia bordering Yemen, she became the head of the state-run hospital’s labour and delivery department, and continued to send home money to support her child after her fiancé unexpectedly died of a heart condition.

As the only foreigner promoted to lead a department there, she carried around a notebook, filling it with phonetically spelled words and phrases until she taught herself to communicate with her colleagues in Arabic. When war broke out in Yemen in 2014, she became accustomed to—and even relished—the adrenaline rush and frenetic pace of managing the department and caring for patients as bombs exploded in the distance. But with her child’s future to think of, Guerrero eventually made the decision to relocate where she could find safety, security, and an opportunity to settle.

She had fully expected to work her way back up the career ladder when she came to Canada under the Home Support Worker pilot program. That program, which ended in June 2024, was designed to bring in workers who had the goal of becoming permanent residents to care for aging or disabled Canadians. Guerrero wasn’t too proud to start over. But that summer in 2022—even though the labour market was clamouring for nurses with the skills she possessed—she was stuck.

Her original work permit was what’s called a closed work permit. It allowed her to work only as a caregiver. And until the IRCC eased its restrictions during the early days of COVID to allow her to provide in-home support to other older adults, she was restricted to work exclusively for the employer who had sponsored her, a middle-aged man with health complications.

It wasn’t that Guerrero wasn’t grateful. Her employer was, as she described him, nothing short of wonderful.

But without an extension or new work permit, she had only “implied” or “maintained” status, which meant she was essentially left in limbo—anxious that at any moment she’d no longer be allowed to stay in the country. There were times, as she wiped down the bathroom of her employer’s North York bungalow after helping him bathe, she questioned whether she had made the right decision to come at all.

What am I doing here? Is this really what I came here for?

If only she were getting somewhere—building a nest egg, moving ahead in her work, or edging toward permanent resident status. If only she were certain all of this would lead to a better life for daughter, who was still back in the Philippines under the care of her aunts.

On more than one occasion, at the end of a long day, she’d stop at a park. It was the only place she could go to be on her own when COVID waves restricted cafes and restaurants to take-out and delivery. She’d sit there in silence with a cup of Tim Hortons, and cry.

God, she prayed, just give me the strength to do this.

Join the thousands of Torontonians who've signed up for our free newsletter and get award-winning local journalism delivered to your inbox.

"*" indicates required fields

For decades, internationally educated nurses, or IENs, like Guerrero have come up against barriers that have prevented them from working in their field in Canada, despite longstanding nursing shortages here. While these shortages existed well before the pandemic, COVID pushed the country’s health care labourforce to the brink, jolting governments and regulatory bodies into action to start dismantling some of those barriers.

In its 2022 budget, for example, the federal government committed $115 million over five years to help as many as 11,000 internationally trained health care professionals get their foreign credentials recognized. Last November, the Ontario government approved changes that, starting this April, will help streamline and simplify the process for IENs to register with the College of Nurses of Ontario, the governing body for nurses in the province.

In spite of these developments, though, many nurses, especially those who arrive here as live-in caregivers or international students, still find themselves shut out of their profession. Their plight pokes holes in the growing public perception, captured in recent polls, that Canada should reduce immigration levels but prioritize newcomers with specialized, in-demand skills. If it’s highly skilled, high-demand immigrants we want, the reality is they’ve been coming here all along.

“The nurse who is not able to work as a nurse, for example, they are the ‘right kind of immigrant.’ We just don’t let them be that ‘right kind of immigrant’ once they get here,” said Daniel Bernhard, chief executive officer of the Institute for Canadian Citizenship.

The way Bernhard sees it, Canada holds an outdated view of immigration. While we’ve always thought of ourselves as a nation of immigrants, we open the door to newcomers with a sense of our own generosity, he explained. We haven’t caught up to the fact that our country, with its aging population, often needs immigrants more than they need us. Especially now, as we face a shortage of affordable housing and an overburdened health care system, the perception that immigrants use up our limited resources overshadows the fact they also produce and contribute to our resources, he said.

“Immigrants don’t just come here to consume. They are producing. They are not just takers, they are makers,” Bernhard said, warning that if we overlook this point, we overlook the value of immigration to our whole society.

It’s in everyone’s best interest to ensure immigrants can thrive here, he argues. “This is not just about immigrants’ well-being and quality of life; this is about Canada’s well-being and quality of life.”

Nurses represent just one such immigrant group whose potential value to the country is often squandered. According to Statistics Canada, internationally educated health care professionals, including nurses, are less likely to be employed than their Canadian-educated counterparts. Those who are employed often find themselves in jobs that don’t take full advantage of their health care training. In 2021, only 58 percent of internationally educated health professionals actually worked in health occupations. And those who are working in health are often overqualified for their positions. In 2021, 21 percent of immigrants working as nurse aids, orderlies, and patient service associates in the Toronto area had at least a bachelor’s degree, compared to just 3 percent of non-immigrants.

As a researcher at Toronto Metropolitan University and PhD student at the University of Toronto, Laura Lam studies the experiences of foreign workers employed through digital gig labour platforms, like Uber and meal delivery apps. Through this work, part of the Canada Excellence Research Chair in Migration and Integration program, she has encountered many internationally educated nurses who can’t practice in Canada and wind up picking up jobs on gig platforms like Taskrabbit, where people hire others to do household chores, or Care.com, for child care, senior care, and housekeeping.

If it’s highly skilled, high-demand immigrants we want, the reality is they’ve been coming here all along.

While some view these gig platforms as a stepping stone toward eventually finding opportunities in their field, others experience them as a dead end. It’s difficult to give up the chance to earn money, however modest and unpredictable, and to find the time and bandwidth to pursue certification or further training.

Her research participants often express a sense of acceptance about not being able to work in their profession. Yet, she said, they “want to give back so much.”

“And I think it really is that tension I found that makes me so sad at times. You hear people who are willing to pay back and give to the health care system but unable to do so, and yet they’re still trying,” Lam said. “They’re like, ‘As long as I’m caring for somebody, I’m happy.’”

The accounts that Lam hears from nurses struggling to get back into health care are hard to reconcile with the needs of the labour force. This past summer, the Registered Nurses Association of Ontario issued a media release emphasizing the urgency of recruiting and retaining more registered nurses. It cited the latest data from the Canadian Institute for Health Information, showing Ontario needs 26,000 more registered nurses to catch up with the nurse-to-patient ratio of the rest of the country.

The “saddest part,” Lam said, is participants will often tell her they have many years of nursing experience under their belt or have worked as a head nurse in another country, but “can’t do anything” here because they don’t have the recognized credentials.

“It just seems like a waste—like a brain waste, to me,” Lam said

Several nurses interviewed for this article said they knew they’d have to start over to some extent and rebuild their careers when they came to Canada. But they didn’t anticipate how long it would take to meet all the requirements needed to practice nursing here. The process of gathering school transcripts from their home countries, having their credentials assessed by the National Nursing Assessment Service, enrolling in bridging programs to address any gaps in their training, taking jurisprudence exams and language proficiency tests, and applying for a certificate of registration with the College of Nurses of Ontario—all of this takes considerable time, and certain courses and application windows are only open at specific times of the year. While Canadian nursing schools prepare and guide domestic students through all the steps they need to enter the workforce upon graduation, foreign-trained nurses often have to navigate them on their own. And time is of the essence; to obtain a certificate of registration with the College of Nurses of Ontario, applicants must show they have experience practicing nursing (which can include volunteering as a nurse) in the past three years. Beyond this timeframe, they would need to take further steps, like taking additional courses, practicing in another jurisdiction, or participating in a supervised practice experience program.

Rodolfo Lastimosa Jr. arrived in Toronto as a landed immigrant, or permanent resident, in 2011. In his home country, the Philippines, one of Canada’s largest sources of immigrant health care workers, he was a registered physiotherapist, midwife, and nurse with a master’s degree in nursing. He not only worked as a nurse in the emergency department of a hospital, he also had six years of experience as a clinical instructor, teaching the next generation of nursing students.

Nevertheless, it took him 11 grueling years to get recertified as a registered nurse here, while he worked as a personal support worker to pay the bills. He is now a clinical manager at Humber River Health.

Mark Gravoso, who is also originally from the Philippines, had a decade of nursing experience when he came to Canada as a landed immigrant in 2017. For seven of those years, he worked at a hospital in the United Arab Emirates, which included taking care of patients in a medical and surgical unit. Yet his credentials and experience were not fully recognized in Ontario. Information about all the steps he needed to take to practice was very difficult to find at the time, and he found that help was almost non-existent.

Gravoso is now a hospital nurse and president of the Integrated Filipino Canadian Nurses Association (IFCNA), a non-profit organization created in 2019 by a group of nurses at the Scarborough Health Network to help address that need. The association, which has more than 5,600 members, provides mentorship, advocacy, guidance, and webinars to Filipino-Canadian nurses, particularly those trained abroad. But, of course, it’s not just nurses from the Philippines who need support, but from all countries, Gravoso said.

“They’re here, so why don’t [we] prioritize all these IENs who are already here, right?” he said, noting that at a time when Ontario is in critical need of nurses, “you see them working at Tim Hortons.”

Local Journalism Matters.

We're able to produce impactful, award-winning journalism thanks to the generous support of readers. By supporting The Local, you're contributing to a new kind of journalism—in-depth, non-profit, from corners of Toronto too often overlooked.

SupportThe consequences of having immigrants who can’t work in their field are manifold. At the individual level, it can lead to dissatisfaction and disillusionment—an outcome that can have negative ripple effects, said Rupa Banerjee, associate professor of human resource management and Canada Research Chair in the economic inclusion of immigrants at Toronto Metropolitan University. In research interviews, she often hears from people who were at the top of the social pyramid in their home countries, only to find themselves at the bottom in Canada. Not only can this hurt marital relationships, she said, but having a parent who’s disillusioned and unable to advance can have a negative psychological impact on children.

Moreover, it’s hardly ideal to have entire communities of immigrants who are dissatisfied and disappointed.

“Those are not the kind of Canadians we want, right?” Banerjee said. “We don’t want Canadians who’re like, ‘Ugh. You know, this is not my idea of a Canadian dream.’”

That’s assuming they even stay. Many don’t. A report published in November by the Institute for Canadian Citizenship and The Conference Board of Canada estimated one in five immigrants ends up leaving Canada within 25 years. Of those who leave, 34 percent go within the first five years.

The country invests a lot into each newcomer, including processing resources, civil services, settlement services, and police checks, according to Bernhard, the Institute for Canadian Citizenship’s CEO. These things are “basically for naught if somebody leaves quite quickly,” he said.

But more importantly, he said, the research by his Institute and the Conference Board shows that economic immigrants—those selected for their ability to address some of Canada’s most pressing needs, including nurses, personal support workers, construction supervisors, and early childhood educators—are the most likely to leave the country. And when they depart, Bernhard said, the needs they were brought in to fulfill don’t just leave with them.

Since the pandemic, it’s become significantly less complex and onerous for foreign-trained nurses—or at least for those who have permanent resident status—to transition to practice in Ontario. While The College of Nurses of Ontario told The Local it could not provide an interview, it pointed to the latest data available on its website, including its 2024 Nursing Statistics Report, which shows internationally educated nurses are now driving an increase in the province’s nursing supply. There were nearly 5,500 who newly registered as nurses in 2023, a three-and-a-half-fold increase from 1,565 in 2019.

Yet even though the process is rapidly becoming more streamlined with the reduction of unnecessary or redundant steps, obtaining approval to practice nursing is only one part of the challenge for internationally educated nurses, said Cameron Moser, senior director of services and program development at the charity ACCES Employment, which supports jobseekers.

We haven’t caught up to the fact that our country, with its aging population, often needs immigrants more than they need us.

There are numerous other barriers that make it difficult for them to secure employment, including all the steps involved in finding and applying for a job, how to succeed in retaining it, and how to get promoted over time. (That last point, retention, is critical for addressing the broader nursing shortage.)

More pre-arrival support—that is, providing information and advice to people as early as possible in the immigration process before they come to Canada—is also needed, he said.

“I know it sounds overly simplistic to say we just need a full community response,” Moser said, but that is, in fact, what’s necessary. Too often, he said, that’s not been the case from the post-secondary sector, the workforce development sector, and governments.

The pandemic has proved, however, that when there’s urgency, a full community response is, in fact, possible.

Ensuring that Canada retains immigrants—and the skills, sense of entrepreneurialism, and dynamism they bring with them—isn’t just a matter for high-level policy makers, according to Bernhard. It’s also incumbent on cities and individuals to consider what makes their communities worth living in. Affordability plays a role, but there are other less tangible factors, like whether one has friends, whether they’re happy, and whether they can get outside and enjoy their surroundings.

“I think we often miss the little stuff,” he said, explaining that even mundane gestures, like inviting people over for coffee, are an important part of making newcomers feel welcome.

In 2020, after her first year in Toronto, Guerrero sent her paperwork to the National Nursing Assessment Service, the Canadian service that assesses and verifies IENs’ credentials. She was informed that her credentials were more closely comparable to those of a registered practical nurse, or RPN, in Canada, but not a registered nurse. In April 2023, she took her RPN exam and passed.

But because she was still waiting on a work permit, Guerrero still could not practice as a nurse.

In May of 2023, after nearly two years with implied status, she was granted an extension on her original work permit. Almost immediately afterward, the IRCC granted her a new one, this time an open work permit with restrictions. This allowed her to work for any employer, but the restrictions meant she was limited to employment as a home support worker, housekeeper, or similar occupation. Meanwhile, she waited for her permanent resident status to come through—a goal that would allow her to bring her daughter to Canada as her dependent, and finally apply for a certificate of registration to work as a nurse again.

Guerrero continued to work as a live-in caregiver for the employer who sponsored her, and she also began working as a personal support worker for a long-term care facility.

Finally, this past October, more than five years after arriving in Canada, she received an email notifying her that the IRCC had granted her permanent residency.

“Congratulations!” the email read. “Your status as a permanent resident is confirmed.”

Guerrero wept with happiness. She printed off the email, and waved the paper around in the air. One of the first things she did was go to St. Barnabas Roman Catholic Church to express thanks for her answered prayers. Next, she bought a plane ticket to Toronto for her daughter Gellaine, now 17.

On a Wednesday in November, Guerrero arrived at the airport with a sign that read, “Welcome to Canada.” As soon as mother and daughter saw each other, they hugged and cried.

In the months since her arrival, Gellaine has started school, and has made new friends. Her schoolmates have all been very welcoming and kind, she told her mother. And every day, they are grateful to be together.

The next step for Guerrero is to apply for registration with the College of Ontario Nurses. (She would have done so sooner, once her permanent resident status made her eligible to do so, but it didn’t make sense to her to register for an annual membership so close to the end of the year.) If she clears that hurdle, she wants to either return to working in the labour and delivery department of a hospital, or become a mental health nurse. After all, she explained, the need for the latter is pressing, so until she can work in nursing, she intends to use that time productively and get trained in mental health.

As she described her imagined future, Guerrero was optimistic.

To finally work in her field again would not just be a victory for her; Ontario would gain a much-needed nurse—one with a gentle manner, perseverance, and who has more than proved her mettle.

The Immigration Issue was made possible through the generous support of the WES Mariam Assefa Fund. All stories were produced independently by The Local.