When Carelle Lahouri first moved to Toronto from Côte d’Ivoire (or the Ivory Coast) in 2019, the thing she missed the most was the food. The 31-year-old had come to Canada in search of work opportunities, eventually landing a job at the Ministry of Labour. And while Toronto has one of the most diverse food scenes in the world, with cuisine from nearly every corner of the planet, Lahouri struggled to find the West African dishes she loved.

“There was lots of food from Ghana, Nigeria, Ethiopia. But no Mali, no Senegalese, no Ivorian food,” she recalls. Early on, she was craving a Senegalese dish but couldn’t find it anywhere, even at the biggest African food festival in the city. “So I knew that there was a need here in Toronto for Ivorian food.”

The Ivorian community in Toronto is small. Because the country is French-speaking, most immigrants to Canada move to Quebec, settling in places like Montreal and Sherbrooke. But the Toronto community is growing, from only about 200 in 2014 to 1,225 in 2021.

Lahouri couldn’t shake the idea of sharing her cooking with more people. Before moving to Canada, she had lived in France as a student and there, she’d begun to practice recipes from home, posting about her culinary experiments on a personal blog. “I started my page for people like me who didn’t know how to cook and who wanted to join my adventure,” she says. A couple years into posting, she was routinely receiving messages asking if she was selling her food anywhere.

In Toronto, she thought, perhaps she could open her own restaurant. “But when I came to Canada, I didn’t have the money, or know the customer base,” she says. Slowly, she built up her savings and started experimenting with an at-home delivery business, selling her Ivorian dishes during the pandemic, all while working her day job.

In May 2023, she finally opened up a brick-and-mortar restaurant called Instant du Palais at Mount Pleasant and Davisville. It’s not a huge restaurant, but Instant du Palais is decorated with cozy bench seating, African art on the wall, and wide front windows that let in the light. Located in the Mount Pleasant Village next to the defunct Regent Theatre and surrounded by other local restaurants, Lahouri’s restaurant is the only place in the city for Ivorian food. Lahouri serves up beloved classics like attiéké (a couscous-like dish made with ground cassava), garba (spiced fried fish), and placali (a cassava dough similar to fufu). And while there’s no shortage of African restaurants in Toronto, Lahouri’s put “Ivorian” front and centre in all the restaurant’s branding, proudly announcing her roots.

Lahouri’s modest ambitions are simply to run a restaurant that serves her country’s food. But in doing so, she joins a long line of immigrant pioneers in this city—newcomers who move to Toronto and decide to set up shop, creating the first integral gathering places that lay the foundation for entire communities.

Toronto is often called a city of neighbourhoods, but more than that, it’s a city of ethnic enclaves. There are multiple Koreatowns, Little Italys, and Chinatowns, as well as places like Little Tehran in North York, Little Tibet in Parkdale, or Greektown along the Danforth. These communities are so ingrained in the fabric of the city that they can feel natural or inevitable. But every immigrant community started with one newcomer opening up a business and making it safer and more welcoming for other people to visit, shop, and settle. Each began with a single shop or restaurant opened by someone like Carelle Lahouri.

Zhixi Cecilia Zhuang, a professor at Toronto Metropolitan University and the academic director of the Toronto Metropolitan Centre for Immigration and Settlement, says that by opening businesses, immigrants create job opportunities and establish familiar neighbourhoods. “People tend to concentrate in these areas because of convenient access to food, services, and resources from their community,” says Zhuang.

The earliest record of Toronto’s Chinese community, for example, can be traced back to a man named Sam Ching, who opened a laundry business at 9 Adelaide St. East in 1878. (Today, a laneway named after Ching adjacent to Adelaide is a reminder of his legacy.) Just a few blocks west, in 1901, the first Chinese restaurant, called Sing Tom, opened on Queen Street, across from the then-brand new, now-old City Hall. Back then, the neighbourhood was called The Ward, and it was the landing spot for newcomers in 19th and 20th century Toronto. It was a notoriously unsafe place to live in the 1900s, with a Department of Health report in 1911 describing the “slum conditions in the Shadow of Old City Hall.”

At different times, the neighbourhood was home to Irish potato famine refugees, escaped slaves, Jewish people from Eastern Europe, and other immigrants. In the 1920s, it had become the hub of Toronto’s growing Chinese community, with 202 Chinese restaurants, making it the city’s first Chinatown. But, in the 1950s, the City expropriated The Ward to make way for Nathan Phillips Square and their new city hall building. Residents and surviving businesses moved west to Spadina or east toward Broadview, where downtown Toronto’s two Chinatowns still stand.

Entrepreneurial newcomers like Ching and Lahouri don’t set out to intentionally build immigrant hubs. But by settling and creating a concentration of businesses, Zhuang says, they’re providing their communities with the direct access to much-needed resources that allow these immigrant areas to flourish. Think Little Tehran in North York or Agincourt in Scarborough, where immigrants have established their own mini-enclaves within the larger suburb. Today, these places have replaced traditional neighbourhoods like Chinatown or Little Italy along College as landing pads for most immigrants, as rising commercial and residential rents have pushed newcomers away from the downtown core.

Some of those downtown areas are now among Toronto’s trendiest neighbourhoods. But just as they were once dismissed as undesirable ethnic slums, today’s suburban immigrant neighbourhoods are often looked down on. The reason ethnic enclaves are now concentrated at the periphery of the city, Zhuang says, is because “these spaces tend to gain less attention, are underdeveloped and underserved.”

That has forced these communities to find ways to serve themselves and share resources, Zhuang says. A newly landed Bangladeshi immigrant may learn about where to find the best affordable ingredients from their homeland by chatting with another, more established Bangladeshi immigrant in Crescent Town. A group of Filipino families may get together to start an informal daycare in Little Manila at Bathurst and Wilson. With cheaper real estate in the suburbs, these communities have a better chance to flourish. It’s this cycle—less expensive housing attracting newcomers, who then create resources for their community, which in turn attract more newcomers—that sustains all ethnic enclaves.

Immigrants are risk-takers who try to reshape the neighbourhoods in which they land. “A lot of innovations take place in the suburbs,” Zhuang explains. “Not just opening businesses, but place-making and reshaping the spaces.” Chinese seniors, for example, routinely transform indoor malls into public gyms by gathering to go on speed walks or practice Tai Chi. “In their new adopted home, they need to find ways to continue their traditions and build community and make social connections with others.”

But suburban ethnic enclaves are still at risk of redevelopment and gentrification. Places like strip malls are seen by planners and politicians as “run-down properties,” ripe for redevelopment. “People don’t really understand the social fabric behind them and the community functions behind them and their importance to the community—those strip malls are like the suburban version of Kensington Market,” Zhuang says.

During the pandemic lockdowns, Zhuang recalls seeing community members gathering in strip mall parking lots outside their favourite restaurants to share takeout meals and socialize, since their usual indoor haunts were shut down—a testament to how integral these spaces are to their communities. “You can’t just demolish these places and replace [them] with a high-rise condominium in the name of intensification.”

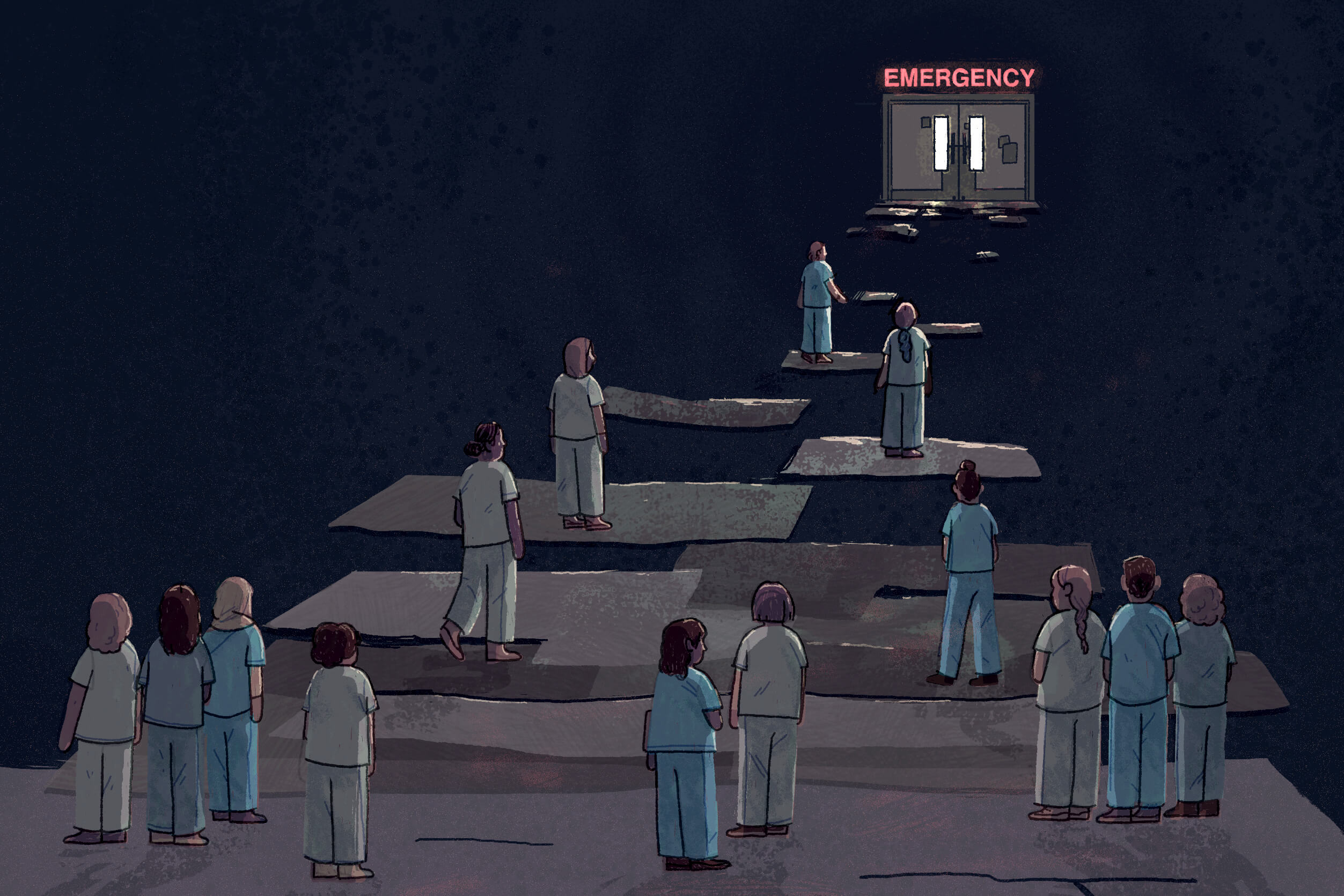

When we think about the future of immigration in Canada, we need to think about what spaces exist for them. Especially as the federal government is locking down paths for immigration to Canada and anti-immigrant sentiment is growing in the country, those who do arrive need places where they can find community. How can we make sure that we’re protecting the places that immigrants call home? And, looking toward the future, how can we create spaces where immigrants can find a sense of belonging?

At Instant du Palais, where Lahouri and her staff serve Ivorian dishes six days a week, it’s not just grilled fish and plantain that beckons diners. As the first Ivorian restaurant in the city, Instant du Palais is already becoming a community institution for a growing population.

In early 2024, Côte d’Ivoire hosted the Africa Cup of Nations, the continent’s biggest international soccer competition. Lahouri’s restaurant hosted viewing parties. All month long, Ivorians and other West Africans gathered at the restaurant to cheer on their home countries. When Côte d’Ivoire cinched their third title in a gripping final match against Nigeria, the packed restaurant exploded in cheers. Overjoyed soccer fans spilled onto Mt. Pleasant, bringing excitement to this typically sleepy part of town. On Instagram, Lahouri celebrated both her home country’s win and also the new home she’s carved out in her adopted country. “I’ve lived this Cup of Nations so far but oh so close to my country,” she wrote.

For Lahouri, it’s a dream come true to serve food from her native country to diners in her adopted country. Providing a space for her fellow Ivorians in Toronto is not just one of the functions of the restaurant, but the primary one. “It’s an Ivorian restaurant,” she says. “I want it to feel like this is really our place.”

The Immigration Issue was made possible through the generous support of the WES Mariam Assefa Fund. All stories were produced independently by The Local.