Over the past 25 years, Toronto midwife Manavi Handa has met with government officials, tussled with doctors, and battled hospital bureaucrats in her fight to provide health care to countless pregnant people and their babies. In 2016, she tended to Syrian refugees temporarily housed at a GTA hotel, using one of the hotel’s rooms as a makeshift clinic. In 2023, when Toronto shelters were turning away asylum seekers, she cared for multiple pregnant women who were sleeping on church floors in the northwest corner of the city.

For Handa, advocating on behalf of immigrant women is second nature, and an integral part of her work. Even in her youth, she was, in her words, “pretty political,” into feminism and anti-racism. And her fiery spirit comes through in the way she speaks—soft-hearted, yet wry and acerbic.

Her own grandmother was raised on the border of Afghanistan and India, in what is now Pakistan. And like so many of Handa’s midwifery clients, her grandmother did not come from great means, and did not know a word of English. So when friends ask Handa whether she ever feels like quitting, her answer is unequivocal.

“It would be like abandoning my grandmother,” she said. “I can’t.”

Access to health care has never been easy for immigrants living in Toronto who are uninsured or who have inadequate coverage. But these days, it’s becoming increasingly difficult. And Handa, who’s also an associate professor of the midwifery program at Toronto Metropolitan University, worries things will get worse.

Amid rising anti-immigrant sentiment and policy changes in Ontario that make health care prohibitively expensive for those without provincial coverage, Handa’s bracing for greater hardship for those without OHIP (Ontario Health Insurance Plan), including non-citizens and those who don’t have permanent resident status.

“I really think we need to realize we’re about to go into a humanitarian crisis,” she said.

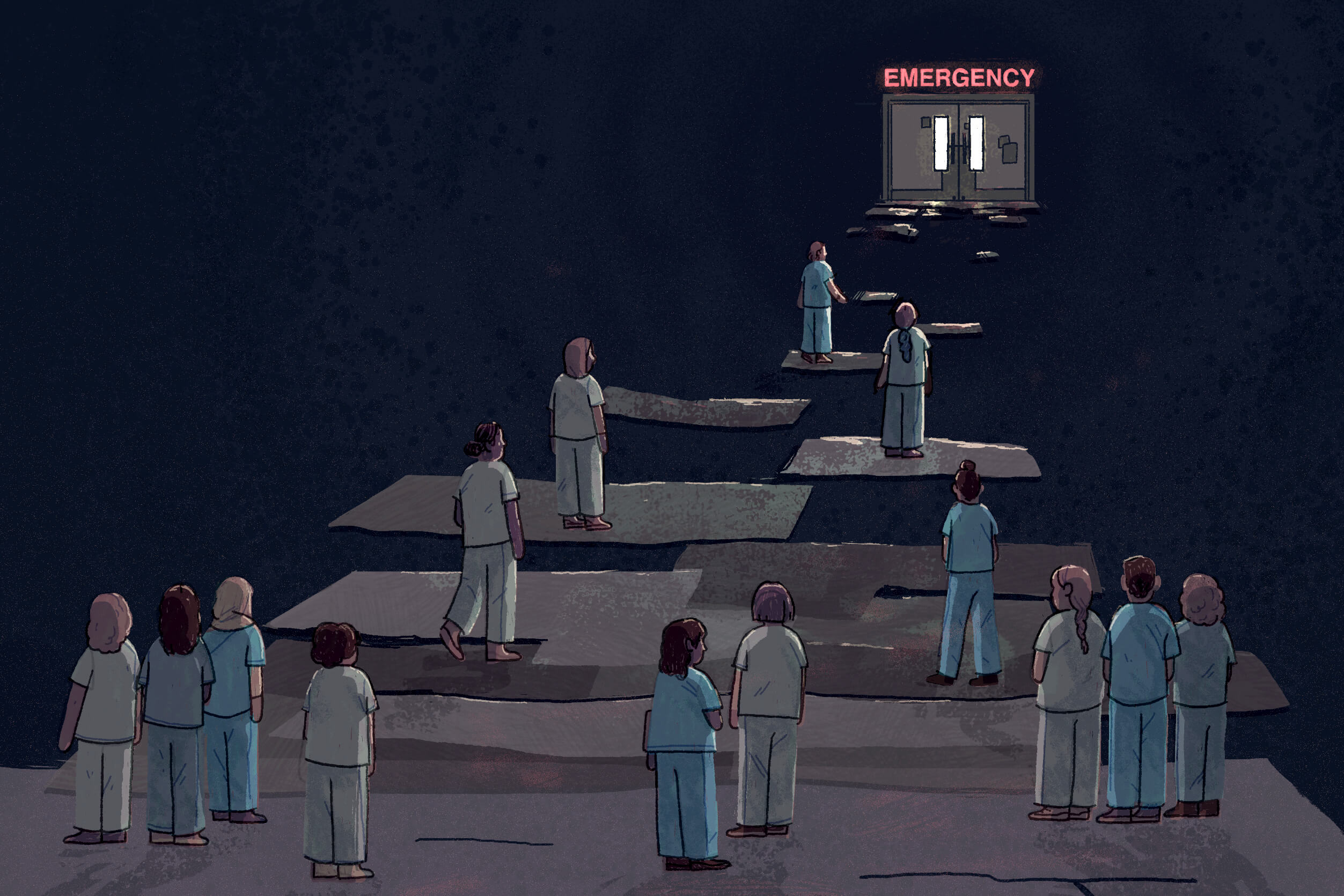

Midwives like Handa are at the forefront of a long fight for universal health care in this province—something that many Canadians assume already exists. The unique history and the funding structure of midwifery in Ontario have put these midwives in a singular position in that struggle, which has intensified over the past two years. After a brief period during the pandemic, when the province paid for hospital care and certain physician services for people without OHIP, access to health care for those who are uninsured and under-insured has regressed. Midwives and other advocates say that access is actually worse for their uninsured clients today than before COVID—to the point where a growing number of people in the city are being forced to make life-or-death decisions about whether or not they can afford to seek care for themselves and their babies.

As a result, Handa said, “There’s going to be a lot of bad outcomes.”

Historically, midwives in Ontario have always served those who don’t have or don’t use provincial health insurance, including Old Order Mennonite and Amish communities. Unlike most health care providers, they do not bill OHIP for their services, nor do they operate on a fee-for-service model. Instead, ever since midwifery was integrated into the provincial health care system in 1994, the care that midwives provide has ultimately been paid for by the Ministry of Health’s Ontario Midwifery Program, and is free to all Ontario residents.

In 2015, using a formula based on Handa’s research, the Kathleen Wynne-led Liberal government extended provincial funding of midwifery care to include things like lab tests, medical imaging, and consultations by specialists. The province also agreed to cover the transfer of care of midwifery clients, so that if they needed an obstetrician to perform surgery, for example, the obstetrician would get paid for it. (While midwives handle healthy pregnancies, they involve specialists if a client develops complications.)

This funding model, unique to midwives in this province, has meant they’ve been one of very few points of access to the health care system for people who are uninsured. That’s also meant midwives have a front-row seat to what happens when people are denied or can’t afford care.

Before the change in 2015, Handa recalls having to engage in what she describes as “disgusting bedside haggling” over how much uninsured clients would be charged, and who would cover the costs. She brings this up because, to some extent, she said, “this is happening again.”

Jenna Bly sees the harrowing consequences all too frequently. Bly is a midwife at South Riverdale Community Health Centre, which serves marginalized populations. Although all are residents of Ontario, many of the centre’s clients are uninsured or under-insured, including people who are in the midst of applying for refugee status or permanent resident status, and those who have temporary work or study permits.

“They’re paying taxes, they’re part of the system,” Bly said. And yet, with the exception of community health centres like these, uninsured residents lack access to most health care services.

On a late November afternoon when I met them, Bly had just finished up with clients for the day and was dressed in scrubs, sneakers, and cool mismatched earrings. In their quiet second-floor exam room, they took a seat atop the examination table, resting their tattooed arms casually over their criss-crossed legs.

Bly explained the community health centre’s MATCH (Midwifery and Toronto Community Health) program offers a full range of reproductive care, including prenatal, labour, birth, and postpartum care, as well as medical abortion, the management of spontaneous abortion, testing for sexually transmitted infections, and pap tests. But while the care they and other midwives provide is free, any time an uninsured client has to go to a hospital, fees are involved. Hospitals charge for things like triage, outpatient clinics, and overnight stays.

Just a few days earlier, Bly had received a referral to see a new client. That client had undergone treatment at a downtown hospital for an ectopic pregnancy, a potentially life-threatening condition where a fertilized egg implants outside the uterus. The bill had come to $10,000. The client was meant to have been followed up by a surgeon, but the surgeon had refused to see her because of her outstanding bill. So a nurse practitioner referred her to Bly.

Situations like these arise from time to time, Bly said. More common, though, is when clients call with signs of preterm labour, like pain or bleeding. Whenever that happens, Bly arranges to meet them in hospital to assess them, so they can consult an obstetrician about any concerns.

“But just walking through the door at triage costs them money,” Bly said. This always presents a quandary: If they convince the client to go to the hospital, and it turns out everything’s fine, the client will nevertheless have to pay an uncertain amount to the hospital, which can erode the client’s trust.

“It’s like, you almost want to find a problem,” they said, to justify the cost.

For a brief period, during the early years of COVID, Bly and Handa and their colleagues were free of such dilemmas. In March 2020, in response to the pandemic, Ontario’s Ministry of Health issued a directive to fund medically necessary care for uninsured residents. That funding program, called the Physician and Hospital Service for Uninsured Persons, covered things like emergency department visits, certain medical procedures, and hospital programs.

“The relief during the pandemic, having this directive, was being able to just have my patients follow my medical advice, without any of this talk of money,” Bly said. “We could just provide the right care, at the right time, at the right place, with the right provider.”

Although it wasn’t perfect (the directive was implemented unevenly and was introduced as a temporary measure), health providers saw their uninsured patients and clients get unprecedented access to care. Clients didn’t need to delay seeking help until they saved enough money, it allowed those who preferred to give birth in hospital to do so without the fear of receiving a bill they couldn’t pay, and it eliminated the moral burden for health providers of having to calculate the risk to their clients’ health against the potential costs of treatment.

“All of a sudden, we went into this magic world, like, ‘Oh my god. This is universal health care,’” said Handa.

That “magic world” was short-lived. When it ended, things only got worse.

Join the thousands of Torontonians who've signed up for our free newsletter and get award-winning local journalism delivered to your inbox.

"*" indicates required fields

Since its inception nearly a decade and a half before the pandemic, the Health Network for Uninsured Clients (HNUC), a group of GTA hospital workers, policy analysts, organizers, and frontline health workers, including midwives, has been advocating on behalf of the uninsured and underinsured.

So when the ministry issued its directive in 2020, the HNUC saw it as a huge win, said co-chair Diana Da Silva. It amounted to the government recognizing what the group had been saying for years, she said: “That in order for us to have a healthy, a fair, and a just society, we need everyone to access health care.” Suddenly, the HNUC’s role shifted to making sure that hospital staff, beyond the executives who received the Ministry’s memo, and uninsured patients were aware of the directive’s existence.

On the whole, the directive brought enormous relief to uninsured people and health care workers alike. As the HNUC noted in a report in the spring of 2023, titled “A Bridge to Universal Healthcare,” uninsured clients were able to seek care before their medical issues became severe or life-threatening; it reduced their stress, no longer forcing them to choose between paying for medical treatment and necessities like food and housing; and it lightened the workload of health care providers, who no longer had to spend considerable time advocating for their clients and finding funding for services.

In late March, 2023, however, the province ended the program. In a bulletin issued two days prior, the Ministry of Health announced the program’s end date of Mar. 31, 2023. “Following the general lifting of public health restrictions, Ontario continues to wind down COVID-19 response measures that are no longer appropriate or necessary,” it read.

The Ministry did not respond to repeated requests for comment for this story.

That week, HNUC members and supporters hit the streets, giving media interviews and protesting in front of Queen’s Park with signs that read “Care Does Not Discriminate,” “Cover Everyone,” and “Health For All Means Access Not Fear.” Their efforts did not sway the province.

HNUC’s co-chairs Da Silva and Shezeen Suleman explained that in some instances, certain hospitals allowed some treatments to continue for their uninsured patients, including those who were in the midst of cancer treatments or dialysis. But by and large, patients were suddenly on the hook for their medical bills.

“People were being asked to pay, virtually overnight,” Suleman said.

Suleman, who is a practicing midwife, is a petite brunette with a soft voice and a competent manner. She recalls that one of her colleagues took a call the night before the funding program ended, from the partner of a client who had received a medical abortion and was in severe pain, with signs of an ectopic pregnancy. Though the couple was instructed to go to the emergency department, they were afraid to do so, mainly because they were worried they couldn’t pay for it.

“We were able to allay their anxieties to be like, ‘There will not be a bill. Go, tonight,’” Suleman said.

It was a mercy that they did. It turned out the client had what’s called a ruptured ectopic pregnancy, which ended up requiring surgery to save her life.

Suleman still thinks about that client often, haunted by what might have been. “If the same thing happened the next night,” she said, “she might not have gone in.”

“I really think we need to realize we’re about to go into a humanitarian crisis”

Rose Halim and her baby are fortunate that they both are healthy and fine, too. As a nurse from Egypt who came to Canada in 2023, Halim said she also feels lucky that she received her open work permit and OHIP just days before giving birth last November, which meant the birth in a GTA hospital was covered by the province.

But the treatment she received in hospital for complications during her pregnancy was not. Last July, Halim, who is using a pseudonym to discuss personal details about her health and finances, was told to go to the emergency department by an eye doctor who discovered bleeding behind her eyes. Even though she told the hospital staff she was uninsured at the time, and wanted only medical guidance since she couldn’t pay for in-patient care, she was advised to stay or risk permanently losing her vision. There, in her second trimester, she underwent multiple tests and procedures, and was seen by several doctors, who found she had high pressure in her brain. This condition was causing vision problems and excruciating headaches.

On the fifth day of her stay, she was discharged with instructions to follow up with a specialist, who gave her medication to reduce the pressure in her brain. The final bill was close to $11,000.

Since the birth of her baby, Halim has been trying to figure out what she can do about her outstanding hospital bill. It’s stressful, she said, but she has no means of paying for it. “So what can I do?”

When Halim came to Canada, she had not intended to stay. But she ended up meeting someone here and getting married. One of the things that troubles her about her whole ordeal is that she feels as though she was treated like a visitor. “I’m not a visitor. I’m married, and I continue my life here. I started my new life here,” she said.

Even before she was hospitalized, she had tried to see a doctor when she first discovered she was pregnant, but was turned away because, as a temporary resident waiting for an open work permit, she did not have OHIP. One doctor agreed to see her, but only if she paid $30,000 at her first appointment. Halim did not have this kind of money.

The idea that uninsured and underinsured residents are tourists, coming to Canada and taking advantage of domestic resources, or to give birth here so their babies can get citizenship, is a misconception that Bly wishes to dispel.

“The people who are living here, who are Ontario residents, who have come to Canada for a better life, they’re not tourists. They’re not going back home,” they said. “This idea of people flying in and flying out, it’s not what I see in my frontline work.”

Local Journalism Matters.

We're able to produce impactful, award-winning journalism thanks to the generous support of readers. By supporting The Local, you're contributing to a new kind of journalism—in-depth, non-profit, from corners of Toronto too often overlooked.

SupportFor uninsured residents and the health care system in general, the end of the province’s funding program in March 2023 couldn’t have come at a worse time. Canada was bringing in an increasing number of temporary migrants, who, as Da Silva explained, tend to be at greater risk of losing their immigration status, and who experience gaps in accessing health care even when they do have status. In Ontario, the estimated number of non-permanent residents jumped from 600,000 in the third quarter of 2021 to nearly 1.4 million in the last quarter of 2024. (It’s unknown how many uninsured residents there are in the province.)

Meanwhile, the provincial health care system was underfunded. A March 2023 report by the Financial Accountability Office of Ontario noted the province had allocated $21.3 billion less to health care than what the financial watchdog projected it would need between 2022-23 and 2027-28. And clinics and community health centres, which serve uninsured clients, were experiencing wage freezes and huge wait lists.

In the months after the funding program ended, midwives and other frontline providers started to notice something else. Some hospitals seemed to be charging uninsured clients whatever they wanted for things like triage or hospital beds—much more than they ever had before COVID, Bly said. Meanwhile, health providers imposed what appeared to be stricter rules than ever, with physicians refusing to see patients. To Bly, it seemed that the rescinding of the government’s directive amounted to a green light for health providers to proceed with a for-profit approach to health care. Not only that, they said: “It’s like from a leadership position, this implicit permission to discriminate against people who are not insured somehow.”

Suleman and Handa also noticed that babies of their uninsured clients were being denied OHIP cards, despite being born in Ontario and meeting the province’s requirements. Those requirements include confirming that the baby’s primary place of residence is in Ontario, and that the baby will be in the province for at least 153 days for every 12-month period.

Handa said she wrote a letter for one client, affirming that her baby met all of the OHIP requirements. And yet, when the client brought it to a ServiceOntario office, she was turned away and told she needed to present a lease or a mortgage in her name to receive an OHIP card for her baby.

“That’s not true. There’s no legal requirement for that,” Handa said.

When I reached out for a response from the Ministry of Public and Business Service Delivery and Procurement, which is responsible for ServiceOntario, a ministry spokesperson referred me to the Ministry of Health. The Ministry of Health did not respond.

Observations like these were documented in a report by the HNUC in August 2024, titled, “Two Steps Back: The Impact of Ontario’s Rollback on Healthcare Access for Uninsured Residents.” It captured a reported rise in discriminatory treatment and harassment toward uninsured clients in hospitals.

Some hospitals seemed to be charging uninsured clients whatever they wanted for things like triage or hospital beds—much more than they ever had before COVID.

The report pointed out there is no provincial oversight or regulation of what hospitals charge uninsured patients, which has led to widely different practices and fees at various hospitals across the GTA. Additionally, since some hospitals offer little transparency about their fees, providers found it difficult to inform their clients about the costs they could expect.

When I reached out to all of the major hospital groups in the GTA to request a list of fees that uninsured clients could expect for various common charges—such as for a visit to the emergency department, day surgery fees, or hospital room charges—most responded with statements about how they provide emergency care to those who need it, regardless of their ability to pay, but few gave any actual dollar figures for what uninsured clients are billed. One of the only hospital groups that did was Unity Health Toronto, which includes St. Joseph’s Health Centre and St. Michael’s Hospital. It said the cost of a ward room for non-residents—that is, patients from outside of the country—was $4,916 per day, and for uninsured residents, it was $2,458 per day.

Some hospitals, like Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre, seek pre-payment. Sunnybrook said when that’s not feasible, it provides treatment without delay and the person will be billed for the care provided. The deposit it requests is $10,000.

At North York General, pre-payment of $6,000 is required for elective, in-patient services. However, both North York General and Scarborough Health Network said information about the various fees it charges uninsured patients needed to be obtained through a request under the Freedom of Information and Protection of Privacy Act.

Through this request, North York General provided a list of its daily rates for uninsured patients, including $780 for an emergency department visit, $3,060 for a ward bed, $1,160 for an MRI (magnetic resonance imaging scan), and $4,643 for an intensive care unit bed. A similar request was sent to Scarborough Health Network, and is awaiting reply.

In an emailed statement from the Ontario Hospital Association, which represents hospitals across the province, president and chief executive officer Anthony Dale said hospitals develop their own processes for collecting payment from uninsured patients, and that this will differ depending on the organization. However, he said, hospitals are often unable to recover funds, either partially or fully, for various reasons, including when the patient doesn’t have the financial resources to pay.

“Some hospitals are facing significant financial pressures from unpaid uninsured services,” Dale said.

The fact that hospitals aren’t able to collect from those who can’t pay makes them something of an unlikely ally in the call to bring back some version of the province’s directive to cover health care for those who are uninsured, Suleman said. “It’s in their best interest.”

Sign-up to our free newsletter and get our award-winning local journalism delivered to your inbox.

"*" indicates required fields

Ask midwives like Handa, Suleman, or Bly why they’ve taken up the fight for universal health care, and they’ll give you plenty of reasons. Foremost, they believe it’s the right thing to do; the way members of the HNUC see it, access to health care is a basic human right.

But they also argue that when uninsured residents are able to seek timely care, it’s less costly and alleviates pressure on the health care system as a whole.

Dale, the Ontario Hospital Association president and CEO, alluded to this point as well in his emailed statement, saying uninsured patients are more likely to delay accessing needed care if they think they will face financial hardship, “which means they may present to the hospital with more advanced and complex medical needs.”

Moreover, as they saw early in the pandemic, covering health care costs not only benefits their clients, it takes a load off of midwives and other frontline providers as well. Handa explains this was the reason she urged the government to expand its coverage of midwifery care back in 2015.

“I couldn’t deal with the bedside nightmare conversation one more time,” she said. “I did it for totally selfish reasons.”

But they have another motive, too—a shared sense that no one is very far removed from the reality their clients face. Handa is confronted with this whenever she provides care to the many immigrant women who remind her of her grandmother. Suleman said her own parents came to Canada as refugees, and went on to live in the U.S. as undocumented migrants for about 15 years. “The issue is very personal to me,” she said.

And Bly, who is American, said they are now seeing the same immigration pathways they took when they came to Canada in 1997 becoming more restrictive. If they were to make the same move today, they don’t think they would have been allowed to stay in this country.

It remains to be seen how changes in immigration policy, both in Canada and by our neighbour to the south, will affect the number of uninsured residents in Toronto in the coming months. (Suleman and Da Silva say that the federal government’s move to reduce its intake of permanent residents will perhaps force some people to remain here undocumented, but they anticipate the vast majority of newcomers who lose their status will opt to leave or try to find other ways to stay legally. No one they’ve ever encountered actually wants to go underground.)

In the meantime, the midwives interviewed for this story say they’ll continue to see and advocate for those who seek their care.

Back in their quiet examination room on the east end of Toronto, Bly may have little power to beat back the wave of hostility that puts their clients—racialized women, queer and trans people, and those living in poverty—in greatest peril. It’s incredibly frustrating, they said, to see people in positions of power making policy decisions that harm those who are most vulnerable. Nevertheless, they told me before packing up for the evening, they have to trust in the fact that they’re doing what they can to take care of their corner of the world, however small.

“So I do my best,” they said, halting slightly as they searched for their next words. ”And…I really wish that the people in power saw what I saw.”

__

Correction—February 7, 2025: A previous version of this article incorrectly stated North York General’s rates do not apply when the reason for the visit is childbirth.

The Immigration Issue was made possible through the generous support of the WES Mariam Assefa Fund. All stories were produced independently by The Local.