On her first day in Canada, Delphina Ngigi slept deeply and for a long time. She had done the hard part: escaped the threats to her life back in Kenya, left behind her four kids, ages nine to 21, travelled over 11,000 kilometres across the Atlantic Ocean, and sought asylum half the world away.

She had to leave, her friend Lydia says, hesitating before explaining why. Delphina, 46, was bisexual in a country that has legally outlawed LGBTQ relationships. In high school, she’d been shunned for a relationship with a girl. But she married a man soon after graduation and raised a family with him for 20 years. After he died last year, she began seeing a woman. In response, someone attacked her at the market. Others tried to burn her house down.

So, she left.

She arrived at Toronto Pearson International Airport on Feb. 15, 2024, with two big suitcases and a backpack. There, she went through the long, complex airport procedure of declaring asylum: go to an agent, show them the visa you travelled with, and when they ask your purpose of visit, tell them you have nowhere safe to go. There’s a lot of paperwork to exchange to prove your need for a new home: identity cards for immigration permits and résumés for a refugee claimant protection application. Documents in hand, Delphina waited for Lydia’s housemate to pick her up. Lydia got home from work at midnight and woke up her old friend for a long-awaited reunion.

On her second day in Canada, Delphina took the bus back to the airport at 6 a.m. to officially submit her asylum application. In return, immigration staff handed her a package of welcome-to-Canada material: pamphlets and flyers with long lists of support services and shelters. One included a phone number for central intake, the helpline for the homeless in the GTA that theoretically directs people to shelters with free beds.

On her third day in Canada—the Saturday of Family Day weekend—Delphina called the helpline and waited for someone to answer. Though they were longtime friends, Lydia couldn’t house Delphina for much longer. Lydia is also an asylum seeker with limited resources and space; her landlord doesn’t permit guests. (The Local is not using her real name to protect her immigration process.) But Lydia knew the shelter system well, having navigated it herself when she arrived in the country to seek refuge the previous June. She knew that going to them directly, one after another, would be more helpful than listening to hold music on the phone.

Join the thousands of Torontonians who've signed up for our free newsletter and get award-winning local journalism delivered to your inbox.

"*" indicates required fields

The two friends took an hour-and-a-half bus ride to Dundas Shelter—an inconspicuous Mississauga homeless facility surrounded by strip malls. It was a frigid snowy day with the temperature hovering between -6 and -8 degrees Celsius. In a video Lydia took, Delphina walks from the bus stop on the side of a six-lane roadway to the shelter. With her jacket hood over a big fluffy toque and thick scarf, she walks slowly in her winter boots and gives a tired smile to the camera as her friend excitedly narrates her first excursion—the beginning of her “life in Canada.”

Lydia told Delphina to go to the shelter while she waited at a Tim Hortons in the strip mall just past the building. “The moment you go to a shelter with someone, they turn you away thinking this person can accommodate you,” Lydia told The Local. The friends stayed in touch over WhatsApp. At around 1 p.m., shelter staff told Delphina they didn’t have space and asked her to wait outside with a list of numbers for other shelters, including the central intake helpline. None of the calls resulted in a bed.

“They never told her to leave,” Lydia says. “When you tell people like us to wait, that means there is hope.”

With hope for a bed, Delphina waited outside in the cold for seven hours.

On her fourth day in Canada, Delphina died.

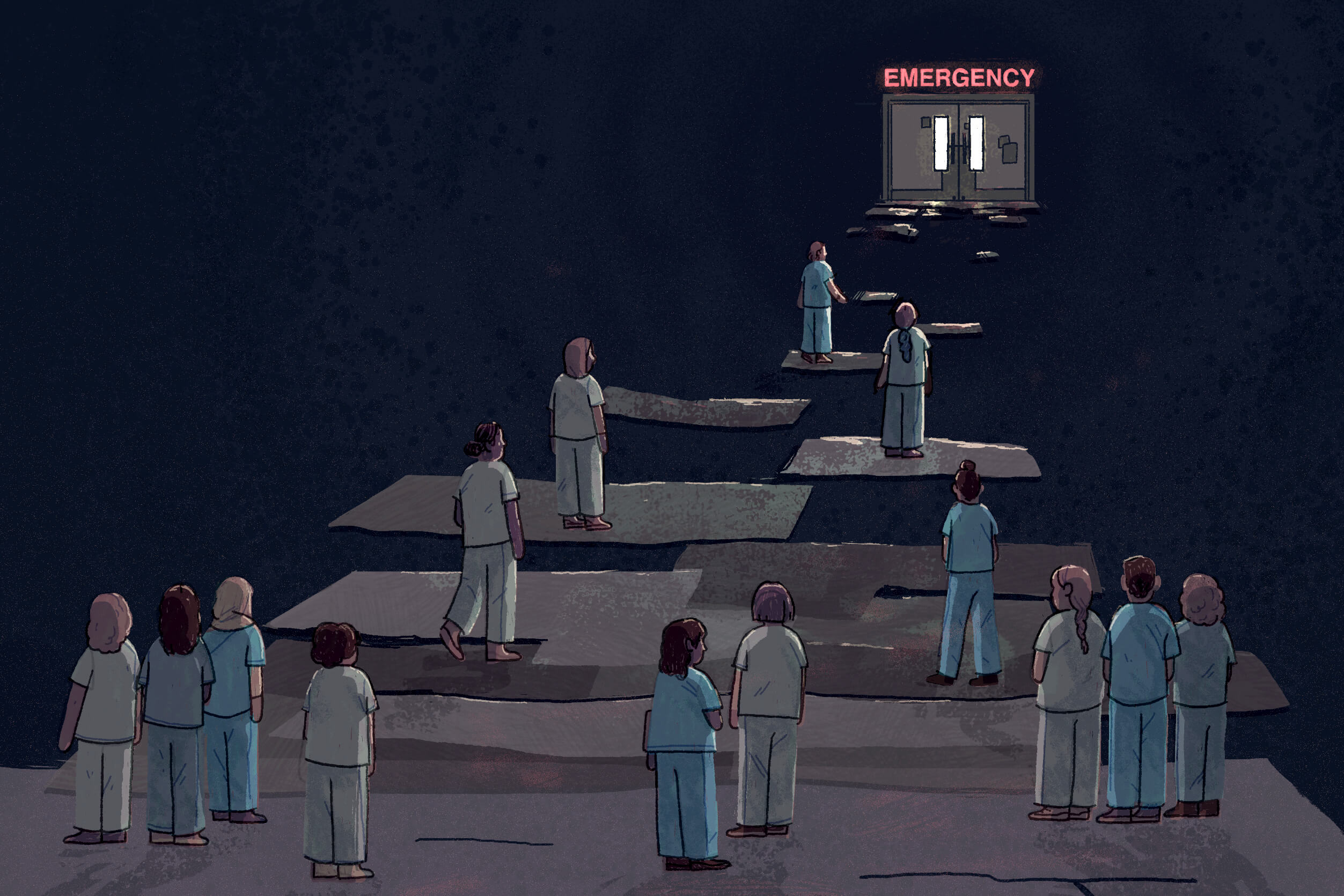

When Delphina arrived at Mississauga’s Dundas shelter, she was entering a system under unprecedented stress.

The Region of Peel—a sprawling suburb just west of Toronto made up of the cities of Mississauga, Brampton, and the Town of Caledon—has generally had a manageable shelter system. That has changed dramatically in the past few years as Peel has found itself in a vortex of crises. In the midst of a pandemic and a housing affordability crisis, the Region has seen a huge influx of asylum seekers with nowhere to go and few means to settle down. Suddenly, issues more familiar to downtown urban centres were in Peel, with encampments and homeless people setting up at highway intersections, in between strip malls, and on the edges of residential neighbourhoods.

As a result, Peel has been left to respond in ways that go far beyond what a suburban government is accustomed to—trying to help some of the world’s most vulnerable people while handcuffed by forces more powerful and complicated than any one municipality can handle.

That response has been marked by tragedy. Before Delphina’s death, another asylum seeker died in a tent outside Dundas Shelter. And just this past weekend, Peel Region confirmed a third person seeking asylum had passed away in the shelter system. They had not released their identity or cause of death at the time of publication. “Our sincere sympathy is extended to this individual’s friends and family,” wrote Renee Wilson, a Peel spokesperson. “Our gratitude is also extended to staff who provide care and shelter to the most vulnerable in our Region.”

These deaths highlight the gravity of the crisis in Peel’s shelters. And with multiple conflicts half the world away and a U.S. president pledging mass deportations, more and more asylum seekers will be looking to deeply overwhelmed and bandaged shelter systems, like Peel’s, for safety.

For decades, the Region of Peel has been one of the only Ontario municipalities with a “no turn away” policy. In theory, this means that if someone—anyone—knocks at a shelter door, a space must be found, even if that space is a corner of the lobby. Under this policy, encampments were also not removed. The policy was designed to be compassionate and responsive. But in the past few years, it has become unsustainable.

The crisis began during the pandemic, when the Region’s shelters worked overtime to house a growing homeless population that had to be separated for health and safety concerns. To manage, Peel turned to an emergency measure it had never used before: it converted hotels into crisis shelters. “As long as I can remember, we would always have shelter overflow contracts in place with some hotels,” says Jason Hastings, Peel’s director of social development, planning, and partnerships since 2017. “You just hope you don’t have to use them.”

When the province declared a state of emergency in March 2020, Peel transferred about 50 percent of its homeless population to five hotels, which were sitting empty as the pandemic halted travellers.

“I remember it being a clear example of how to address COVID-19, but also other health issues,” says Dr. Lawrence Loh, then the-medical officer of health for Peel. “The idea that if you give people their very basic need of a roof over their head, everything else falls in place.”

When the pandemic-shuttered borders opened fully again in 2023, Canada saw a sharp rise in the number of asylum claimants, with the majority landing at Pearson. There were multiple reasons for this: Canada relaxed its asylum policies, and a greater number of people around the world were being displaced because of overlapping crises and conflicts. Plus, travel was cheap when the world opened up again, and by extension, so was seeking refuge and safety.

The Region wasn’t prepared for the number of people who arrived; no city was. Historically, asylum seekers and refugees did not remain in shelters for prolonged periods, transitioning quickly to permanent housing. But a crippling housing unaffordability crisis and lacklustre settlement supports have led to a huge increase in the number of homeless refugees in a shelter system not designed to help them. According to a report by the Association of Municipalities of Ontario released this month, between 2021 and 2024 the number of chronically homeless asylum seekers and refugees rose nearly sixfold, from 1,834 to 10,552.

When Delphina arrived last February, Peel’s shelters were trying to accommodate quadruple the number of people they usually housed. Before July 2023, asylum seekers took up an average of four to five percent of space. By the summer, more than 1,500 refugees occupied 71 percent of Peel’s shelter beds.

The impacts were visible across the Region. “I would never have imagined there would be tents in the middle of a subdivision in the suburbs,” says Zena Chaudhry, CEO of Sakeenah Canada, whose mandate includes providing transitional shelters for women and asylum seekers in Ontario. Peel’s shelters were underfunded and overworked, she says, and their phones were ringing off the hook. Sakeenah saw a 700 percent increase in shelter requests during COVID, almost half of whom were asylum seekers. The shelter system was collapsing, she says. “There was no central way for all the shelters to contact each other so we were doing it ourselves.”

Peel turned 10 additional hotels into crisis shelters just for asylum seekers. The provincial and federal governments helped foot the room bills. Social workers and nurses visited every day with health care support. Food services and banks supplied the meals. Community members stepped up for anything and everything else: legal support, clothing, the search for permanent housing, and fun.

The Local spoke to 25 asylum seekers, social workers, shelter operators, elected officials, and homeless health experts who all commended Peel’s response. They described it as “compassionate,” “creative,” “responsive,” and “necessary.” The system worked, they say. It literally saved lives.

But it wasn’t enough.

“When Toronto is full, the overflow goes to Peel”

In the summer of 2023, for the first time in its 50-year history, Peel shelters turned people away. By the time Delphina arrived, 300 asylum seekers had been left to fend for themselves because there were no beds anywhere in Mississauga, Brampton, or Caledon. Peel’s shelter system had never been this strained.

To cope, Peel boosted its hotel-turned-shelters, transforming a temporary measure into a permanent band-aid solution. “There was no other viable alternative, frankly,” Hastings says. That was true during the pandemic and true again when the asylum crisis “hit so hard and fast.”

“We just don’t have empty housing facilities sitting around to shelter people,” Hastings added. As he recalls, the Region kept looking at the spike in asylum seekers, wondering if it would subside and things would go back to normal. “They didn’t,” he says. “The new normal is a pretty steady volume of asylum claimants coming in every week.”

For the past year, the Region has been fighting for funding to create a dedicated system to handle these asylum seekers—a rare move by a municipality, as immigration is a federal responsibility.

“We’re trying to get there, but it’s really hard,” Hastings says. But doing so is the difference between life and death.

Peel’s shelters reached a tipping point in July 2023, when dozens of refugees and asylum seekers, mostly from African countries, began camping outside a shelter on Peter Street in downtown Toronto. They had been directed there from the airport, but the shelter was at capacity and didn’t have spare beds. It had already been turning away asylum seekers for a month.

So they turned suitcases and scraps of litter into a makeshift refugee camp in the heart of the city’s financial district. For five weeks, asylum seekers—mostly Black from Nigeria, Kenya, Uganda, Ghana and Tanzania—slept on concrete with only cardboard to cover them.

Brampton resident Gwyneth Chapman was one of the first to respond to their needs as a volunteer and concerned citizen. “I’m not a mushy emotional person but I just burst into tears,” she says. A City of Brampton staffer, Chapman tried to call her municipal contacts to get the asylum seekers into a school, a gym, anywhere safe from the weather. She sent videos and photos to all her group chats, alerting anyone, everyone to help.

One of the first to respond to Chapman’s “bat signal” was Pamela Dolphy. She’s lived in Brampton for 40 years and, as a resident, worker, artist, and longtime community volunteer, watched the city “go from nothing to something.”

Dolphy works at a medical supply company near the Dundas Shelter, and regularly visits to deliver collected blankets, clothes, socks, gloves, and food. “You’re bombarded by the crowd because everyone needs things. They’re so desperate, they’re tripping over each other to get to you,” she says. “The worst feeling is when you run out of food or stuff. It’s never enough.”

When she arrived at Peter Street to help last July, Dolphy watched an airport shuttle bus park at an intersection and unload six people with suitcases. The bus left quickly, and the group joined the crowd, slowly dragging their suitcases until they found a free square of pavement to sit on.

“It felt like a third-world country, but it was downtown Toronto,” she says.

Chapman and Dolphy stayed at the encampment the whole night, until about 2 or 3 a.m., amid the wind and rain. By daylight, volunteers in Brampton and Toronto began transporting people to churches, shelters, and their own homes.

“I thought we’d get them off the street, take care of them, get them community, medical help, translators, paperwork, and everything would be fine,” Chapman says. “But it wasn’t. People kept coming, and nobody was helping. So, we had to do a lot of ripping and roaring to get them all beds.”

Suddenly, asylum seekers became pawns in this jurisdictional battle over who is responsible for housing them—and in this case, no government seemed willing to step up. The federal government is in charge of the system that brings people to refuge and the province dictates housing policy, but municipalities oversee the shelter system.

A recent report by Toronto’s Ombudsman found the City’s response was “unfair, poorly planned, and inconsistent” with the municipality’s commitment to housing as a human right. The Ombudsman also deemed that this lacklustre response to African asylum seekers constituted “systemic discrimination” and anti-Black racism in the report, which the city manager has refused to accept.

“Imagine you leave your home, escape some horrors and come to a new place, only to live on the streets,” says Michelle Meghie, another volunteer and longtime Mississauga resident who responded to the situation.

For these volunteers and advocates, there was but one immediate solution on everyone’s lips: send them to Peel, which would not turn them away. And according to Meghie, the volunteers moved walls to create new spaces for asylum seekers in the suburban shelter system.

“When Toronto is full, the overflow goes to Peel,” says Kizito Musabimana, founder of the Rwandan Canadian Healing Centre. Asylum seekers at Peter Street, he says, were already being told to go to Peel by Toronto shelters, and in that moment, there were a lot of good intentions but no centralized, coordinated effort. “It was very clear this was not a priority,” he says. “And everyone knows: Peel will put you up.”

The overflow from Peter Street required the Region of Peel to open additional hotel-turned-shelters and get approval and funding for new shelter space from regional council, but all of that took a lot of time. When it comes to asylum seekers, “when governments are slow to respond, people fall through the cracks and die,” Musabimana says.

And that’s unfortunately what happened. Four months later (and three months before Delphina’s death), in November 2023, a Nigerian man in his 40s died in a tent outside the Dundas Shelter. Little is known about him; immigration officials told The Local they can’t share details.

“Globalization feels so real in Peel because when things erupt in other parts of the world you see it on your doorstep”

After the death, Hastings, Peel’s director of social development planning, drove to the parking lot full of tents opposite the shelter and watched people comfort each other. “Staff are feeling the deaths, 100 percent,” he says. “We care deeply about these people…It’s not lost on us.”

Hastings says there were “extenuating circumstances” in both this death and Delphina’s that he is unable to share. But he agrees with advocates and social workers that those deaths weren’t the first indication the system was struggling—just the results of warning signs ignored.

Weeks after the death, Dolphy saw another airport shuttle bus drop off a woman and her six-year-old boy at the intersection just past Dundas shelter. There were already dozens of people camped outside. “I took her inside and asked where I could take her,” Dolphy says. “They didn’t have an answer for me.”

“It was just heartbreaking for me,” she says. “I assumed the government would rent a warehouse, rent a hotel, rent something and put them somewhere safe. But it’s been left up to the shelter to create space that doesn’t exist.”

When Peel took in Peter Street claimants, it entered uncharted territory. “Helping asylum seekers has never been the jurisdiction of municipalities,” Hastings says. “But you know, the buck stops with us effectively. People land in our communities and you have to help them, and so that’s what we do.”

The challenge, he says, is the Region can’t sustain providing this kind of support on its own. To start, the shelter system is designed to help the domestic homeless population and not asylum seekers, who often don’t have the means to rent or buy homes until they’re granted permits to live and work here, which can take months, sometimes years.

“From day one when you enter into a municipal shelter system, we are working with them to start to plan their exit, right?” Hastings says. “These are always viewed as short-term stays, but being an asylum [seeker] isn’t a short-term situation.”

Then there’s the challenge of costs for cash-strapped municipalities like Peel. While hotels have helped to manage the shelter overflow for now, sending hotel bills to the federal government couldn’t be a long-term strategy, Hastings says. It’s expensive for taxpayers: one hotel room costs about $220 per day, whereas a bed in a shelter would cost about $90 a day.

Hastings says there are logistical challenges, too. Hotel-turned-shelters are comfortable, so there is less incentive to move into independent housing. Plus, coordinating with settlement agencies requires a large and inefficient use of human resources.

For all these reasons, Peel urged the federal government to help them establish the first welcome centre in the Greater Toronto and Hamilton Area—a hub in central Mississauga where all asylum seekers can come to straight from the airport and stay for five days while someone helps find them housing somewhere in southwestern Ontario that has space and ability to host them properly. After months of back and forth, delays and repeated promises, last summer, Peel received $22 million to build and operate this centre, along with two additional asylum-focused shelters.

The welcome centre opened the first of its four floors on Nov. 1. The plan is to eventually have 680 beds over two floors, with the remainder of the building dedicated to settlement work, mainly figuring out where the best available temporary homes are. The federal government has reimbursed 95 percent of the Region’s $50-million hotel bill and $22-million operating costs for the two new asylum shelters. But by 2026, the federal government will only cover 75 percent of these costs, increasing the cost burden on Peel and any other municipality sheltering asylum seekers.

The federal government is justifying this by pitching a national system of “sustainable, permanent transition housing” for asylum seekers. The idea is to create multiple reception centres and “leverage the full shelter capacity across a number of Ontario municipalities,” and across the country, Hastings says.

He likes the idea but it does nothing to help him right now. “And it won’t help me probably for another six to 12 months,” he says, maybe longer. It’s unclear how quickly the federal government can set them up with enough employees and beds to handle a growing flow of people. The conversations are ongoing between the two levels of government. “There is no simple answer but we are confident that with full engagement from all levels of government, we can implement real long-term, sustainable, and compassionate measures that will ensure that the most vulnerable newcomers to Canada have a roof over their heads,” says Jeffrey MacDonald, a spokesperson for Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada, in an email to The Local.

Until then, the Region is doing everything it possibly can to bolster its two asylum-focused shelters, Hastings says. By February, only three hotels will be used as overflow spaces. Still, the gaps are much bigger than what one of Ontario’s largest municipalities can do, and maybe that’s why Chapman and other social workers remain skeptical.

Social work isn’t an exact science: it’s about people and how systems and institutions respond to their evolving needs and wants. Having a welcome centre is “a good thing but it’s not a solution,” Chapman says. Will it have an updated list all the time of space availability in every shelter across the region, maybe the province? Are there backup plans in case shelter spaces run out again? Will the federal government better coordinate with municipalities next time there’s a spike in asylum seekers so they’re not caught off guard? Will asylum seekers know what to expect once they walk out the doors of the airport?

Local Journalism Matters.

We're able to produce impactful, award-winning journalism thanks to the generous support of readers. By supporting The Local, you're contributing to a new kind of journalism—in-depth, non-profit, from corners of Toronto too often overlooked.

SupportThere are no answers to these questions, which is concerning when everyone agrees that helping a rapidly growing population of homeless people, including asylum seekers, is just going to get harder. “It’s only going to get worse and worse,” Chaudhry from Sakeenah Homes says. Even though the federal government has put a temporary pause on immigration, which includes limiting refugee and asylum applications for the first time, Peel is expecting asylum seekers to increase in its shelter system.

By Peel’s calculation, there are 250,000 non-permanent residents in the Region. Hastings expects 220,000 of their visas to expire under the new pause. There is a “pretty realistic risk,” he says, that many of these people stay in Peel. “Without access to any government support and the desperation that breeds, that means that, somehow, they might end up in our system just to survive,” he says. “I’m afraid for us; it’s a bit of a wait-and-see approach.”

That’s because there are also other unpredictable global forces and pressures at play. Hastings is already working with colleagues across government levels to prepare for an influx of claimants from Gaza and Lebanon, where conflict continues to displace massive numbers of people. This month, U.S. President Donald Trump will take office with a promise to deport 11 million undocumented people. To put that in context, Peel’s newly expanded shelter system can support 1,280 asylum seekers. If even one percent of those deported from the United States (or 110,000 people) ended up in the GTA, the system would be beyond overwhelmed.

“Never have I seen geopolitical events and other things taking place in the world have such a dramatic and direct impact on work we’re doing on the ground in Canada,” Hastings says. “Globalization feels so real in Peel because when things erupt in other parts of the world, you see it on your doorstep because…Peel sort of absorbs the world,” he says. “I can’t imagine a bigger melting pot of different people all coming together in the same community.”

But as everyone keeps repeating over and over again, there are dire repercussions of messing up in this work. And while Peel Region may be leading the way in showing a possible compassionate and collaborative response by creating a system from scratch, at least one person who could have benefitted suffered the consequences of a system unprepared to help her.

On Feb. 18—her third day in Canada—Delphina waited outside Dundas Shelter alone for seven hours, experiencing the full strength of her first Canadian winter day. There’s no place to sit outside the shelter except pavement and frozen grass.

At 8 p.m. the shelter let her into their reception area—a small entryway with no seating, surrounded by locked doors—and told her to sit on her backpack. At 11 p.m., the shelter gave her a chair. A man gave her a phone charger to use; she didn’t have one.

“I thought she was fine,” Lydia says.

The next day—Delphina’s fourth day in Canada—just before 3 p.m., Lydia visited her, a phone charger in hand. Delphina said she had received breakfast but not lunch, and was hoping for dinner. She had seen two people be taken to other shelters and was optimistic she’d get a bed. Lydia told Delphina to refresh with a shower, then left her friend.

Barely an hour later, Lydia got a call from a social worker at Trillium Hospital. “Do you know Delphina?” the voice on the phone asked. Delphina had collapsed in the shower. She was initially conscious and awake in the hospital, but died from a cardiac incident at 4:30 p.m.

That night, Lydia took the bus to the hospital and confirmed that her friend was dead. She went back to the shelter to ask what happened; the shelter wouldn’t talk to her.

Staff and police said Delphina died of natural causes, but Lydia diagrees: “It was an overwhelmed system.”

“When you seek asylum at the airport, you shouldn’t just be let go with a number. Where is the follow-up? Where do these people go? Where is the responsibility to take them to a safe place?” she says. “When you seek asylum, it means you have nowhere else to go. You’re not a visitor. You’re not a tourist. You’re someone who needs a lot of help.”

On the fifth day after Delphina arrived in Canada, Lydia sorted through her bags. She found a to-do list in a box. Four passports, one for each of her children. Four dollar signs next to them, the amount she needed to collect for each.

Lydia shredded that list last April.

“People come to Canada because they think it can help them,” she says. “But how much is Canada prepared to receive them? They didn’t receive my friend.”

The Immigration Issue was made possible through the generous support of the WES Mariam Assefa Fund. All stories were produced independently by The Local.