In the waiting room of the Toronto small claims court, tacked to a puncture-scarred and discoloured corkboard, hangs a laminated sign with service hours and instructions. The court is open from 9 a.m. to 11 a.m. and 2 p.m. to 4 p.m.: four hours in total for the one, maybe two court staffers to attend to the growing number of ticket holders seated across from the front desk, waiting for their turn to be called. If the current speed of service is any indication, some may not be seen today, a possibility for which this courthouse seems prepared. “OBTAINING A TICKET DOES NOT GUARANTEE SERVICE,” the sign clarifies.

On this cool and cloudy Thursday morning in May, one woman has been waiting since the court opened to file an affidavit for an action involving her employer. But her number hasn’t been called by 11 a.m.; with a three-hour lunch break looming, she may just give up for the day. Another man, after trying and failing three times to file a claim online, arrived from Ajax around 10 a.m., and has settled in for a long wait.

It is something that has become synonymous with recent small claims litigation: waiting. With the system still reeling from pandemic-era closures, some litigants have spent years waiting for their actions to move forward, all while bearing the brunt of justice delayed.

In the aftermath of COVID, Ontario small claims courts have stalled, lagging far behind the post-pandemic recoveries of other Ontario court systems. The Local’s analysis of Ontario court data obtained from the Superior Court of Justice suggests that, despite a growing case backlog, small claims courts were still operating well below pre-pandemic levels as of 2022, over two and half years after the courts were first suspended.

Known as “the people’s court,” the Ontario small claims court handles civil claims under $35,000 (anything over is handled by the civil court system). Civil claims are, in essence, lawsuits for money: litigation over a business crumbling and payments owed, for example, or the damage from a car crash. Small claims court is meant to serve as a streamlined forum for civil justice, an efficient alternative to the convoluted and costly civil court system.

“People who use small claims court are [more] likely to be low income, [more] likely to not have a lawyer representing them,” says John No, a lawyer at Parkdale Legal Clinic. Unlike in the civil court system, litigants can hire paralegals as their representation, with rates more affordable than most lawyers. And though the dollar amounts claimed in small claims court may be lesser than in the civil court, it is no less busy. Roughly half of the province’s civil litigation claims go through the small claims court.

But as the civil court system in Toronto recovered to 144 percent of its pre-pandemic processing rate in 2022, the Toronto small claims court operated at just 67 percent.

Taken as a whole, the data paints a picture of who and what is given priority access to the justice system.

To best capture the post-pandemic recoveries of the civil, family, and small claims court systems (complete data for the criminal system was not provided), The Local compared the number of documents processed by each system in Ontario between 2020 and 2022 relative to the numbers in 2019, the last year untouched by pandemic interruptions.

As can be expected, all court systems experienced a drop in 2020, given the impacts of the pandemic. However, the 2021 and 2022 numbers suggest that the civil and family courts bounced back far quicker than small claims court. And though the gulf between civil and small claims was province-wide, it was most pronounced in Toronto, the province’s most active civil court system.

The Local spoke to several paralegals and lawyers who practice regularly in small claims court, and they consistently said the Toronto court was one of the worst to navigate over the last few years. Another GTA courthouse, the Brampton small claims court, was also regularly mentioned as being plagued by delays, something that lawyer Jennifer Fehr and her client have experienced first hand.

Fehr is a supervising lawyer specializing in labour law at Downtown Legal Services, the University of Toronto Faculty of Law’s legal clinic. Her client is a gig worker, operating his own small business providing translation services. The client approached her after a large translation services company failed to pay his bill. Had he been a traditional employee, his rights under the Ministry of Labour could have helped resolve the dispute within half a year or so, Fehr estimates. As a gig worker, though, if he wanted to get paid, Fehr’s client really only had one option: small claims court.

When Fehr’s client filed his action in Brampton in May of 2020, the court was frozen.

“Small claims was basically closed for a year,” Fehr says. “Very, very, very little was done in that year.”

Fehr’s client was in a bind. He needed the money. But as things stood, there was no way to hold his employer to account. While his action languished in litigation purgatory, he found himself taking on more jobs with the same employer, hoping that they would pay down their alleged debt in bits and pieces.

Local Journalism Matters.

We're able to produce impactful, award-winning journalism thanks to the generous support of readers. By supporting The Local, you're contributing to a new kind of journalism—in-depth, non-profit, from corners of Toronto too often overlooked.

SupportFehr explains that her client would have preferred to cut off ties with the employer entirely, but he was afraid of relying on a legal action that was showing no signs of moving. “He was trapped in this employment relationship,” she says. “He was trapped by the debt he was unable to resolve.”

It’s not just a matter of delayed resolution. As an adversarial legal process like litigation is bogged down, and steps which are supposed to take months end up taking years, the incentives within that process become distorted: leaning into the delay can become a strategy in and of itself.

John No, whose legal practice focuses on worker’s rights, says that the delays have compromised his clients’ leverage when they sue.

“The defendants seem to know that it’s going to be forever [before] they even have to think about it—so they’re not feeling the urgency,” says No. And “because a lot of these workers are living paycheck to paycheck, because they need the money now,” many end up settling for a lesser amount.

Most litigation cases do not actually make it all the way to trial, which makes settlements all the more important. Usually, the looming threat of trial is enough to bring both sides to the table, with each intermediate step adding a dose of pressure. That pressure is something that Jennifer Lillie, a lawyer focusing on consumer protection claims, has relied on in the past to quickly settle some of her cases.

Lillie has represented several litigants in small claims lawsuits over what she describes as “door-to-door scams.” As CBC reported last year, certain HVAC rental companies have allegedly been pressuring homeowners into signing up for equipment upgrades, and have included fine print clauses in the contract that enable the company to place a lien on the customer’s home without their knowledge—essentially holding the title to the property hostage until the homeowner pays a ransom, explains Lillie.

“Most of these cases,” Lillie says, “tend to settle [around] the settlement conferences”—an initial small claims litigation step in which the parties are usually brought before a judge to settle on whatever issues possible. But until March of 2021, the scheduling of settlement conferences was very limited, so these HVAC rental companies could just sit tight with their hostages.

With the roof over their head literally under threat and their day in court so far out of sight, Lillie says that some homeowners just paid the companies off rather than wait. “The small claims court just isn’t moving fast enough to provide any meaningful access to justice for them,” she says, so the HVAC rental companies end up with exactly what they wanted.

“The small claims court just isn’t moving fast enough to provide any meaningful access to justice.”

The entire Ontario court system has been plagued by delays since before the pandemic, says Hamilton lawyer and legal process advocate Michael Lesage. The Superior Court of Justice, which has jurisdiction over criminal, civil, family, and small claims cases, “was building up something like a 60,000 a year case backlog in the years leading up to 2019,” he says.

“Effectively, even without COVID, the system was on the verge of collapsing.”

And COVID certainly did not help. The courts paused and the backlogs, untended, grew wild. Faced with few options, other court systems began to adapt, holding virtual hearings, modernizing and digitizing filing systems. But the Ontario small claims court remained stuck in the mud. It was a halting resumption, with different elements of the court process reintroduced in the years since. For over a year and a half, until December 2021, the Superior Court of Justice suspended a significant bulk of their scheduled small claims hearings “due to COVID-19.”

According to a timeline of court operations provided to The Local by the Superior Court, small claims only began scheduling remote trials for new matters on July 23, 2021, well over a year after the initial pause. Key hearings to enforce outstanding orders for payment were paused until June 1, 2022.

“I am waiting on trial dates still on matters commenced in late 2019 and early 2020,” says paralegal Jahne Baboulas. Before COVID, “most actions were dealt with in under two years.”

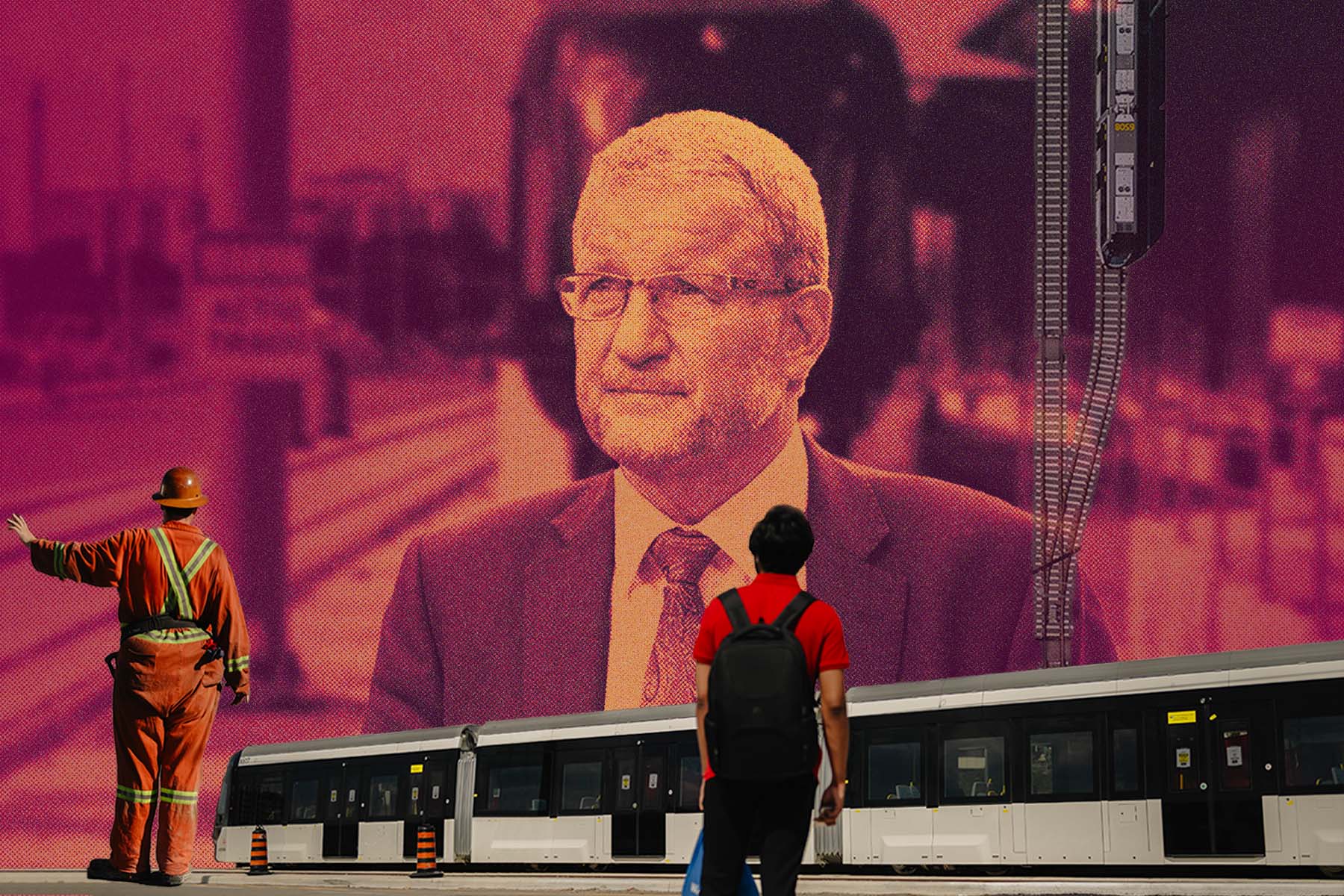

A frequenter of the Toronto small claims court, Baboulas had written letters to court administrators in October 2020 asking why the small claims court was still shut down while almost all the “higher courts” were taking steps to reopen. The letters reached the offices of the Chief Justice of the Superior Court and Attorney General, who share responsibility for running Ontario’s Superior Court. Their specific managerial duties, however, are distinct from one another—an administrative compartmentalization meant to protect the independence of the courts. But it’s clear this siloing has also broken down the accountability process when it comes to delays in the courts.

In their eventual responses to Baboulas, seen by The Local, the offices of the Attorney General and the Chief Justice each avoid accepting responsibility, instead suggesting that the delay is related to matters under the other office’s control. The letters from the Chief Justice’s office say that the delayed resumption of operations was caused in part by insufficient staffing of small claims court, a responsibility that falls to the Ministry of the Attorney General.

The Attorney General’s office, in contrast, made no mention of staffing shortages or resource allocation in their November 2020 response to Baboulas, instead pointing out that the Chief Justice’s office manages scheduling responsibilities.

While both offices said in late 2020 that efforts were being made to resume small claims operations, this sluggishness has persisted well into 2022, The Local’s analysis shows. The delays raise questions about whether the post-pandemic recoveries of other court systems were prioritized at the expense of small claims—whether gig workers and labourers are being left behind as the courts focus on cases where more money is at stake. “[With] the lack of resources put into small claims court,” says John No, “I do wonder if there is a certain lack of priority given to the type of issues [and] demographics that the small claims court serves.”

When reached for comment for this story, the Ministry of the Attorney General reiterated that scheduling was outside of their mandate. “To preserve judicial independence, the ministry cannot comment on or interfere with the scheduling of cases or judicial resources,” they said.

They did not answer The Local’s questions about staffing, nor did the Superior Court of Justice when reached for comment.

“Effectively, even without COVID, the system was on the verge of collapsing.”

The finger-pointing in the face of this crisis doesn’t inspire confidence in the court system. “The Courts and the Ministry need to work in concert in order to get justice done in the province,” says Trevor C. W. Farrow, dean of Osgoode Hall Law School, and a scholar on access to justice and legal process. Without such cooperation, people relying on court decisions to get them out of financial and contractual limbo will inevitably fall through the cracks.

The effects of delays and inefficiencies in undermining justice is something of a hot button issue for those involved in the justice system. A few months ago, the Advocates Society, a non-profit professional association of judges, lawyers and advocates, released “A Call for Action on Delay in the Civil Justice System.” The sprawling report is part of a concentrated push to improve “access to justice” in Canada.

The entire justice system has become so strained, in fact, that as far back as 2016, the Supreme Court was having to address a “culture of complacency” in criminal court, which also led to massive financial investment in the system in 2021. But ensuing efforts to prioritize and expedite criminal matters has put extra pressure on the civil and family courts, such that the backlogs of those systems are starting to balloon “out of control,” says Farrow.

The offices of the Attorney General and the Chief Justice each avoid accepting responsibility, instead suggesting that the delay is related to matters under the other office’s control.

In the wake of the pandemic, the main justice forums for some of the most vulnerable Ontarians have become even more inaccessible, says Douglas Judson, partner at Judson Howie LLP and chair of the Federation of Ontario Law Associations.

“Depending on where you’re situated, the small claims court is a gong show. The Human Rights Tribunal is a disaster for everyone… and the [Landlord and Tenant Board] is a nightmare,” explains Judson.

The Local has previously written about delays in the Landlord and Tenant Board, revealing that tenants wait an average of five months longer than landlords to have their cases heard as of 2022.

But unlike with the Landlord and Tenant Board, court data in Ontario is rarely made public, which compounds the issues arising from the fractured chain of command over the court system. Courts have no obligation to release data on their case management, and even before the pandemic, in 2018, the Superior Court of Justice stopped publishing annual reports on court structure and governance. The next year, Ontario’s Auditor General was stonewalled in its audit of court operations, denied access to key information regarding how courts were run, including scheduling.

“It is dramatically important that we have an understanding of how courts work, where the efficiencies and inefficiencies lie, and how we might do justice better,” Farrow says. “And I think everyone needs to be on board including lawyers, judges, court staff—everyone.”

The administration of justice is faltering. And as the delays pile up, the pressure forces the system to prioritize what it deems most urgent. The small claims court—“the people’s court”—was not just slowed by the pandemic, as other court systems were: it was largely stopped, for a very long time, and the people using it were left to wait.

Jennifer Fehr’s gig worker client is still waiting to collect on the money he says he is owed for his hard work. Even after he eventually secured a court order against that employer in February 2023, nearly three years after his claim was first filed, he still has not been paid. Right now, no one can say when he will get what he says he’s owed.