To Peter Leslie, the hotel seemed like the perfect set-up for an overdose: there was a sense of chaos, with staff running around, residents isolated in their rooms, and security guards, not trained to interact kindly with traumatized poor people, roaming the halls.

Leslie has a lot to say about his experience as a peer worker in the spring of 2020 at the Four Points by Sheraton, a hotel converted by the City of Toronto into an isolation and recovery site for homeless Torontonians diagnosed with COVID-19 or awaiting test results. The sixty-one-year-old has years of professional experience working with unhoused people who use drugs. He also acknowledges, without hesitation, that he uses illicit drugs himself and has been homeless. His own experiences, he says, allow him to understand some of what his clients in the shelter system are going through. “You feel like you’re under surveillance, like you’re an animal,” says Leslie. “You become paranoid about anybody being in your business.”

Leslie says he was in conflict with his supervisors at the Sheraton from the start over what he saw as a dangerous setting for drug users—a significant population among shelter residents. People were dopesick (in withdrawal from opioids) and desperate. There was nothing to do but read, watch TV, worry about dying from COVID, or, for those who had brought drugs or managed to acquire them, get high.

The Sheraton is one of nearly twenty “shelter hotels” rented by the city since March, when COVID-19 began sweeping through our crowded shelter system. They are, by necessity, located all over the place—in Scarborough, near the airport, downtown. Once leased by the city, they’re typically managed by non-profit operators such as Dixon Hall or the Salvation Army. There’s a Howard Johnson, a Super 8, and two Holiday Inns. Some are boutique hotels—a vastly different experience than sleeping in a tent under the Gardiner, in a row of tightly-packed cots in a shelter, or upright in a chair in a warming centre.

But for many homeless people who rely on extremely localized services and on transportation by foot, being torn from their downtown support networks has made what ought to be a safe environment much riskier. Without very careful attention to people’s emotional needs—and in the case of people dependent on opioids like illicit fentanyl, their physical need for a stable and constant source of opioids—such a move can set highly vulnerable people up for death by overdose.

“You’ve got supplies, drugs, and you’re alone,” says Leslie. He insists that overdose deaths weren’t simply a risk—they were inevitable.

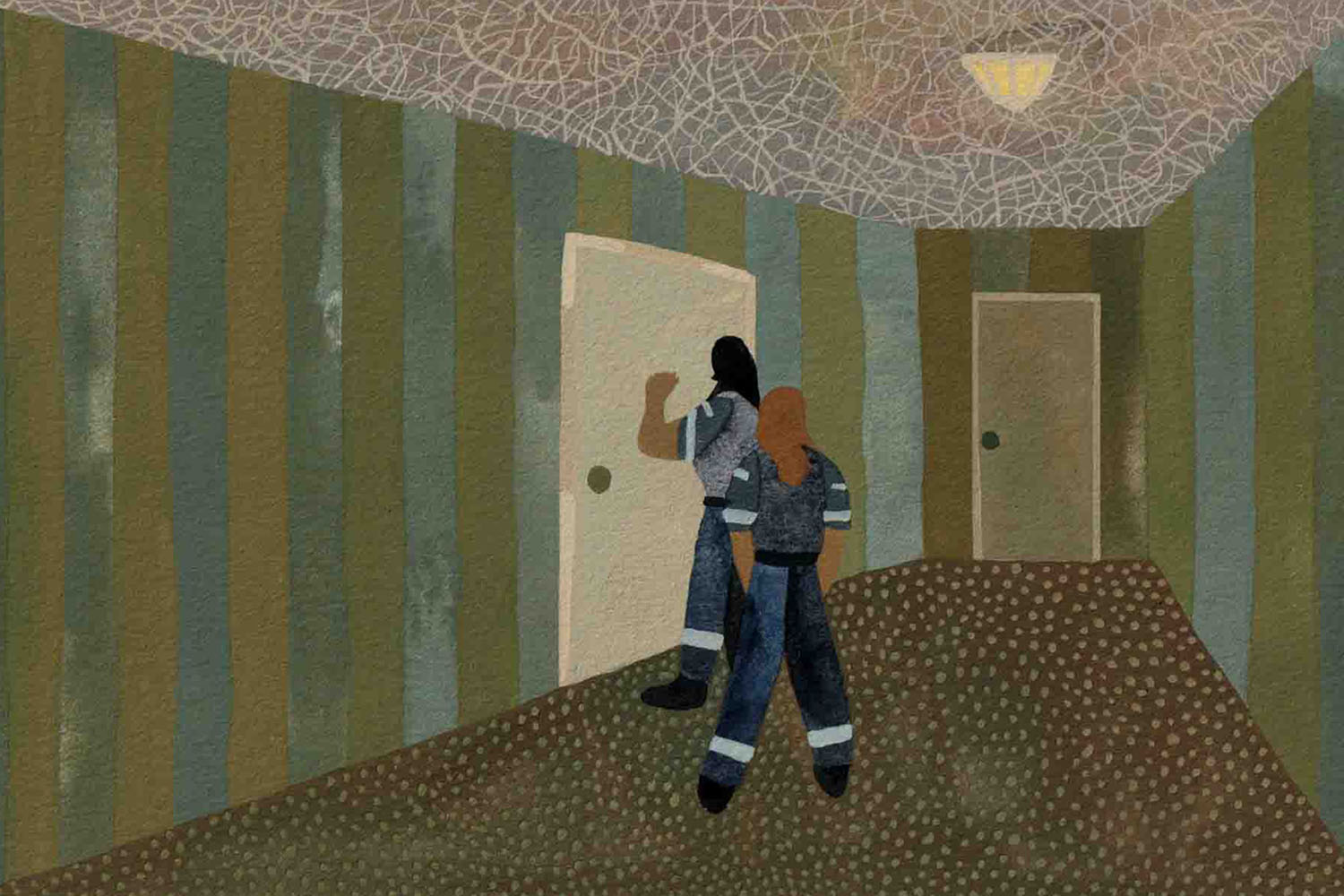

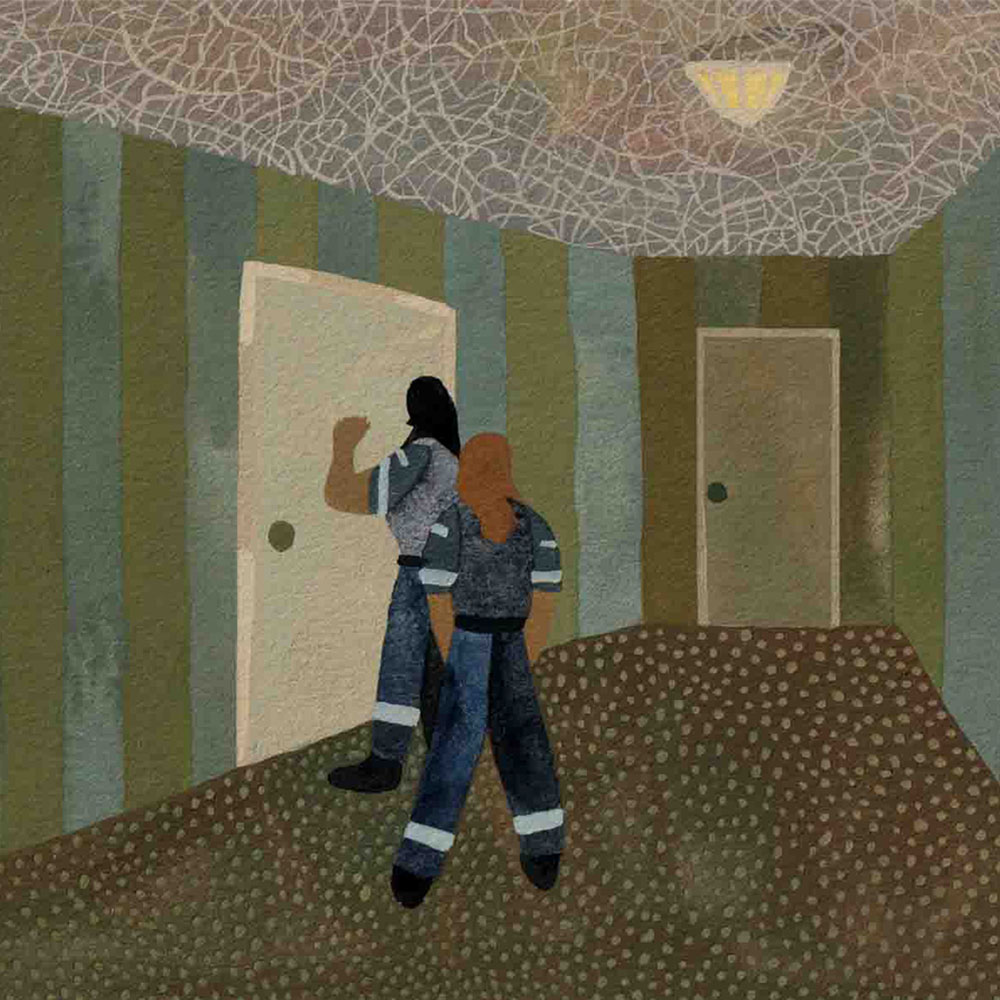

On the afternoon of Saturday, May 16, a resident overdosed and died in his room at the Sheraton. He was found at shift change, his untouched lunch still in the hallway. Leslie didn’t learn about the death until two days later, when the last staff person to see the man alive—a 21-year old recent communications graduate with no harm reduction training—came to him in tears with the news. “This guy died in the middle of the fucking afternoon with nursing staff down the hallway,” says Leslie. He says his coordinator never responded to texts seeking further information, prompting him to quit the following week.

Gab Lawrence, who manages harm reduction at the Sheraton, insists that a significant harm reduction effort began there in April, well before the May 16 death. As the only COVID isolation/recovery site in the system, Lawrence says the Sheraton is miles ahead of all the other shelter sites when it comes to harm reduction. At the Sheraton, new residents are provided with a “substance use menu”—a discrete way to self-disclose drug use and request access to the addiction medications methadone and buprenorphine or to prescription alternatives to illicit opioids. Paid peer workers try to connect residents to whatever harm reduction resources they need. People using drugs in their unit can request “witnessing” by peer workers. But Leslie says he wasn’t even aware of the substance use menu when he was employed there. And his colleague at the time, Megan Lowry, notes that it wasn’t often used in practice—sometimes simply because informal conversations between peer workers and residents seemed more natural.

Gord Tanner, director of the City of Toronto’s Homelessness Initiatives and Prevention Services, would not reveal the name of the man who died on May 16, or any of the other residents who have died of overdose. Ultimately, Tanner believes, the death was tragic, but not necessarily preventable.

The overdose at the Four Points by Sheraton was not a one-time tragedy. According to Tanner, every hotel has most likely had an overdose by now, with 390 having occurred across shelter programs since the start of the pandemic. In July, Toronto suffered 27 suspected fatal opioid-involved overdoses—the worst month in city history. Nine of those deaths occurred in the shelter system and five of those, Tanner recalls, were in the hotels. Toronto’s Shelter, Support and Housing Administration (SSHA) does not keep official records that separate out overdoses and deaths in the hotels from the shelter system at large, so he cannot say how many deaths occurred at the hotels in other months. We do know that there were 54 deaths (of overdose or any other cause) in the shelter system as a whole between January and October of 2020 compared to 39 over the same period in 2019, and 22 in 2018.

So how is it that residents are overdosing and dying in hotels run by the city and non-profit agencies with trained staff and an official commitment to harm reduction? That can only be answered by stepping back to consider Toronto’s three-pronged crisis: a lack of affordable housing, a pandemic that requires physical distancing, and an already-escalating overdose crisis that makes such distancing acutely dangerous. Against that grim background, the shuffling of homeless people from one emergency situation to the next, with little or no autonomy or support, has made a difficult situation that much more perilous.

Harm reduction is official policy across the shelter system, but there’s no consistency about what that means in practice.

COVID-19 arrived in Toronto via the respiratory tracts of people with the means to travel. And yet it was clear from the beginning that the virus would soon find its way to those housed in shelters and bound by poverty to a few city blocks.

It found a system that was already chronically, dangerously overcrowded, with a roughly 98 percent occupancy rate on any given night. For nearly twenty years, homelessness and housing advocates have argued that some shelters, with cots on the floor a few inches apart, violate the UN’s standards for refugee camps. Even before the pandemic, a growing number of encampments and clusters of tents had taken hold across Toronto—a homeless person-led response to the problem. Since March, donated tents have sprung up like mushrooms in every park downtown as people seek to avoid crowded shelters like, well, the plague.

The encampments were a logical response to the chaotic conditions in homeless shelters. And they proved effective for physical distancing: no cases of COVID-19 have been identified among encampment residents, while 649 people had contracted it in Toronto shelters as of October 1. But the sight of poverty in public spaces can be frightening and distasteful to more well-heeled residents, some of whom petitioned the government to remove encampments. The city and the police forcibly cleared homeless residents from public parks (a moratorium that put a temporary halt to this practice expired in May). Tents and belongings were frequently trashed, with residents given as little as an hour to decide to accept an offer of temporary housing in a hotel far away from their community and under unknown conditions.

Sabrina Sutherland is one homeless resident who has experienced the decidedly mixed blessings of the hotel shelter plan. A member of Attawapiskat First Nation, born in Timmins and removed from her family and community by the age of four, Sutherland, 46, has been both homeless and insecurely housed in Toronto over a difficult two decades in which she raised her daughter, studied at Ryerson, and worked as judicial assistant. (Sutherland contributed to a story for The Local in 2019.)

When she began using crack cocaine, she says, it was to try to cope with multiple life traumas. “It helped me to feel complete numbness and stopped my mind from racing and having constant negative, even suicidal thoughts,” she says. Although she quit crack long ago, Sutherland is currently dependent on illicit fentanyl.

When the pandemic began, she moved up to Saugeen First Nation and spent her entire ODSP income on rooms in a series of cheap motels in Southampton, Ontario. “I basically self-isolated as we were all told to do,” she says.

When Sutherland got word that tent camping was allowed in the city, thanks to the temporary moratorium, she moved back to a tent on the University Avenue median, a twenty-minute walk from the Moss Park overdose prevention site. But that didn’t last long.

“Streets to Homes scooped me up with everyone else there and took us to the Broadway,” Sutherland says. The city rented the Broadway, a mid-town hotel with 125 residential units, at the start of the pandemic and used it as a shelter hotel for a few months. It’s ultimately slated to be razed and turned into—what else?—luxury condos. “It was very rough living there, I was robbed and stolen from every couple of weeks,” she says.

It’s not that there were no attempts to keep drug-using residents safe. Measures at the Broadway included sharps disposal containers in every room and naloxone, the opioid overdose reversal medication, available at the front desk. It was OK, Sutherland tells me, to use drugs in your room. Guests from outside were not allowed—but residents were also told that if they left for an extended period, they would lose their space, and phones were not available for residents without their own. So-called “wellness checks”—a way of making sure residents haven’t overdosed, as well as to check in on any concerns they may have—occurred night and day, with staff not always waiting for a response to their knock before entering.

But the full range of supports and protections for preventing overdose were lacking at the Broadway, as at most of the shelter hotels. There was no mental health, addiction or harm reduction counselling. “Not even for suicidal thoughts,” Sutherland says. Unlike her downtown set up, there was also no overdose prevention site near the mid-town hotel where people might use drugs under the supervision of trained staff who can revive them with oxygen or naloxone. “The staff did not seem well trained about opioid dependency or withdrawal,” says Sutherland. “They were jail guards essentially. It felt like living in jail, with some freedom to go outside in the community. The neighborhood was hostile towards us<.” Harm reduction is official SSHA policy across the shelter system, but there’s no consistency about what that means in practice. There seems to be little or no communication in many hotels to ensure both drug-using and non-using residents understand that harm reduction is fully embraced, and that drug users have the right to use safely and without shame. In the SSHA’s rush to move people out of shelters en masse—a rush that became more urgent as shelter residents exposed crowded conditions and housing advocates took the city to court to compel better physical distancing measures—harm reduction may not always have been top priority. Staff had to be redeployed from other city jobs, and so were untrained or barely trained in harm reduction. (The city says training has been ongoing, and workers new to harm reduction are supposed to be paired with more experienced staff.)

For people who are physically dependent on opioids like heroin or fentanyl and who inject several times a day, any interruption to their use is dangerous, as it reduces opioid tolerance, making them far more likely to overdose the next time they have access to the drug. And yet, despite the documented effectiveness of prescribed opioids in preventing overdose death, safe supply is not an option on the table now for shelter hotel residents anywhere except at the Sheraton isolation/recovery hotel. Medically supervised, comfortable detox and quick, low-barrier access to addiction medications methadone or suboxone are similarly not available; from, the point of view of residents on the verge of opioid withdrawal, the route to getting support for safer use or addiction treatment is murky, slow, and laden with risk.

And while isolation is the best way to prevent transmission of COVID-19, it can be deadly for people who use drugs. “When you use, they want you to use in your unit. So if you OD, you’re alone,” says Chris Bell, a past resident of two shelter hotels, including The Bond. Bell smokes crystal meth and says he would have made use of a supervised consumption space if one were available. Instead, although residents at The Bond were eventually allowed to visit each other’s rooms, staff were downstairs. “You’d literally have to wait for the elevator” in order to seek emergency help, says Bell. His unit was on the 16th floor.

Part of the problem may be a lack of general understanding that harm reduction isn’t just a single procedure, like handing out sterile needles. Rather, it’s a philosophy that involves building relationships with deeply vulnerable, repeatedly criminalized people and learning how to meet their needs in order to reduce the risk of substance use. This means it’s dynamic, responding to specific user-identified needs in specific situations. And respect, autonomy, and support for people who use drugs are not just frills, but fundamental to making it work. Getting this wrong means courting death.

While isolation is the best way to prevent transmission of COVID-19, it can be deadly for people who use drugs.

For Gord Tanner, given the challenges in quickly sheltering and distancing people, the shelter hotel experiment could already be considered a success. He describes the increasing collaboration between previously siloed services like mental health, community health, and homelessness since COVID-19. And Tanner sees the hotels as having already proven an important point: “People can be successfully housed in a small apartment.” The city is actively seeking to purchase some of the hotels they are leasing, and hope that federal dollars can help them do so. This could be the first step towards dismantling our “emergency” shelter system and replacing it with real homes, real privacy, real community, real support.

But from the perspective of the people in these sites, and those who advocate for them, it’s too little, too late, and with far too much self-congratulation.

“I would like to believe the shelter hotels are a good idea for COVID because I advocated for them,” says Zoë Dodd, a prominent harm reduction advocate who works for the South Riverdale Community Health Centre. “But I did not advocate for people to be coerced away from their networks…I supported people in taking options that have become deadly.”

Dodd means this literally. One of her harm reduction clients was a man who was dependent on illicit fentanyl and deeply avoidant of shelters. Although he was a long-time tent resident, when all the other homeless people in his encampment were abruptly packed onto busses by city staff, he joined them, ending up at the Edward Hotel. Two days later he had died of an overdose in his room.

In response, Dodd and other harm reduction advocates formed the Toronto Hotel Overdose Action Task Force Project, offering to perform a kind of supportive audit to shelter hotel sites. But eight months after the city started leasing hotel spaces, it has still not created a focused table that includes harm reduction experts and people who use drugs who can identify and respond to needs in a targeted fashion. Dodd believes it was irresponsible of the city to move people who rely on local overdose prevention sites without first making sure there was a robust overdose prevention plan in place. This would include overdose prevention sites in every facility; releasing information that would help target interventions to the hotels that most need them; immediate access to trauma-informed medical care including counselling; micro-induction onto suboxone (an addiction treatment); and prescribed safe supply.

“We’re not asking for an impossibility,” Dodd argues. A lack of consistency across sites, and a reluctance to move swiftly and decisively on those measures, even as they moved quickly to uproot people from tent cities, means that the hotels remain more dangerous than they should be. “If you are going to move a whole park of people, you need to ask them what are their survival needs,” says Dodd. “I think there’s an acceptance from the city that people will die in their shelters.”

While all of us in Toronto wrestle with the question of how we came to be a town where some people speculate on multi-million-dollar homes while others don’t have a roof over their heads, we do have the means to ensure temporary spaces are at least safe for all who need them. The city urgently needs to establish a robust, consistent set of harm reduction policies with a twin focus on earning the trust of homeless clients and on international best practices if they are to prevent further overdose deaths in the hotel shelters.

For some people who lack a secure and permanent place to live, drugs may provide security, comfort, and rest: feelings we associate with coming home. Most importantly, a home is a safe place. Without front-line and drug user experts having a place at the decision-making table to ensure harm reduction measures actually prevent harm, these are far from being homes away from home.

In July, Sabrina Sutherland was moved yet again, this time to Lazarus House, a transitional housing apartment. Technically, Lazarus House is a step towards her goal of permanent housing, but for Sutherland the transition felt like more of the same. For a start, she wasn’t given a choice. “I would have preferred to go to the Bond, which is where the other Broadway residents were placed,” she tells me.

In fact, life at Lazarus House has been difficult. “There is no hot water in my shower so I wash in the sink,” she says, though even the sink only gets lukewarm. “There is a big hole in my ceiling from some water damage when the roof leaked before I came.” The backdoor has no lock. Occasionally people come in and steal her food.

Shuffling homeless people like Sutherland from one inadequate emergency situation to the next continues the city’s practice of offering help that feels more like coercion—only stingily sharing information with people anxious to know what they’re signing up for. “I have no supports at the moment, except the Moss Park safe injection site, and Sanctuary,” Sutherland says. Those spaces are far from where she is now. As has occurred so many times in her life, she has once again been plucked from a community she knows, to a situation where she feels entirely alone. “I could die here and no one would know or find me, probably for days,” she says.

In November, Sutherland was once again considering a move. Having been scooped, moved, and coerced from one grim housing situation to another—having experienced shelter hotels and the full range of the city’s harm reduction strategies during the pandemic—she was weighing her options. “I’m thinking of moving back to the tent encampment,” she said. “Maybe next week… soon.”