The Local: Who are you and where are we right now?

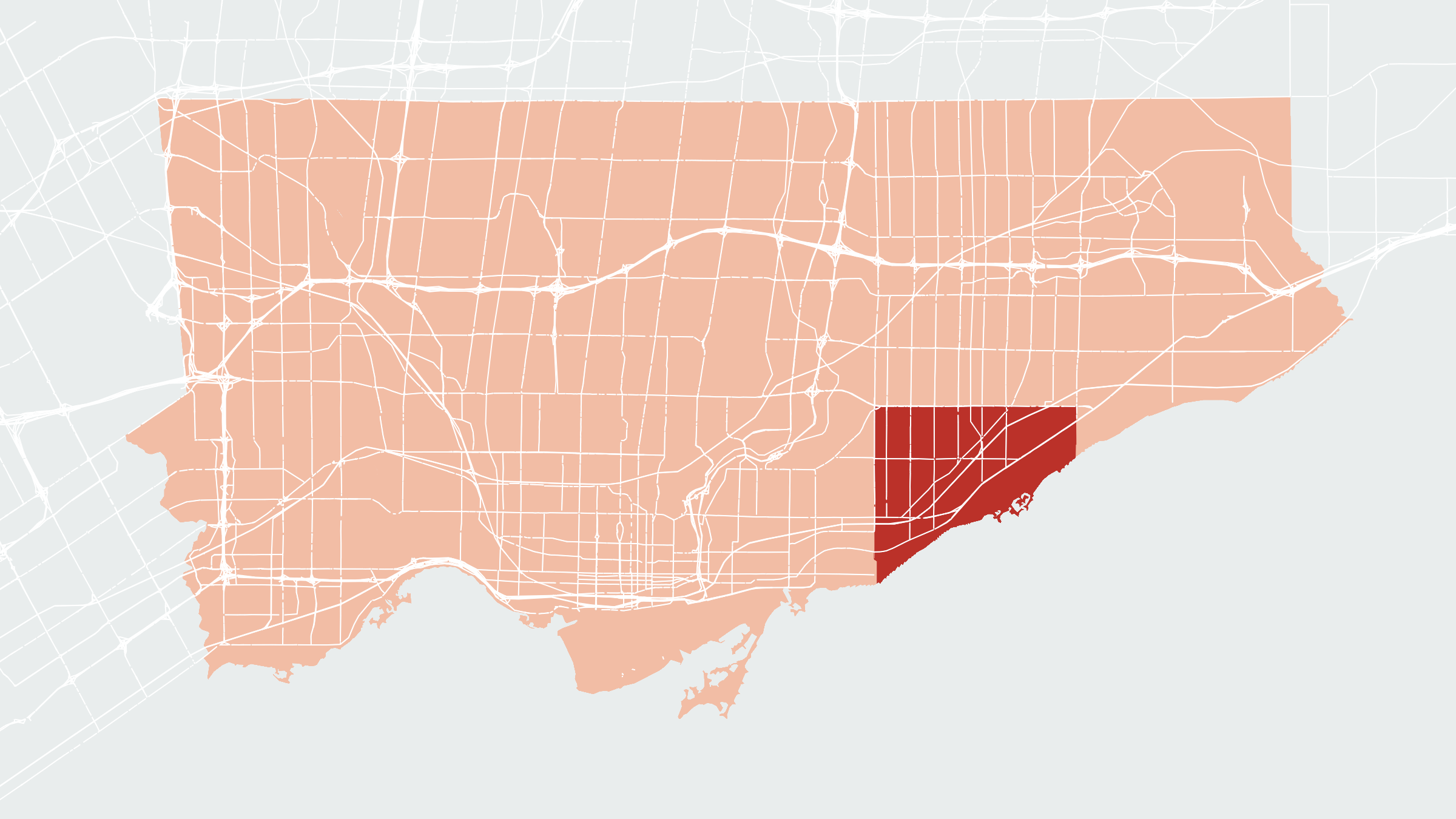

Bev Leaver: I’m the the Executive Director of Stonegate Community Health Centre. We are located in the middle of 75 apartment buildings in South Etobicoke. It’s a little community that not many know exists because there aren’t any major transit lines that go near us.

The people who live here are on average getting poorer and poorer. We used to be part of a plaza that included a grocery store, but that land was bought by a developer in 2014 and torn down. Right now we are the lone building standing on a construction site.

The Local: How did the community respond to the grocery store closing?

BL: When the demolition was going to happen, we got the community together to identify how big an impact losing the grocery store was going to be for this community. We learned that many people can’t afford to use TTC to get to the next nearest grocery store. A lot of seniors said ‘I think I’m going to have to move. I’ve lived here for 40 years and I think I’m going to have to move because if I can’t get food, I can’t stay here’.

The community identified some ideas for how we could cope. One idea was to get a grocery store back, which we have taken as a lobbying challenge. The second was having a mobile food market come, so now we have Food Share’s mobile food market come every Friday night.

For the Senior’s, we partnered with ESS Support Services to arrange for their bus to pick up seniors at their door and take them grocery shopping once a week. We also have a Good Food box program where individuals can purchase two weeks worth of fruits and vegetables for $18 from the CHC.

The Local: Would you call this a ‘food desert’?

BL: I do call it a desert. I don’t know about the strict definition in terms of how many kilometers from you need to be, but kilometers for a young healthy person and kilometers for a senior with mobility issues in walkers or scooter is an entirely different thing.

The Local: What is the impact of food insecurity or food deserts on chronic disease?

BL: Nutrition is important. For almost every chronic condition, there is a recommendation about a diet that would be optimal. If we don’t address that, than we’re just waiting for people to get sick and waiting for people to go to hospital. We will end up spending more money in the long run. The province funds social services, they fund income support, they fund health care, and they fund transportation — so why can’t we work together? It would probably be the same dollars spent, but it would be spent better so we can prevent illness.

The Local: Some people might say that it’s not the health system’s role to provide access to food. Why did you decide to invest in food?

BL: I think healthy nutrition is fundamental to health. If we only have our professionals advising that our clients eat healthy and not following through with giving them the means and skills to live on a budget, to eat healthy on a budget, to prepare food in a way that is going to be healthful, then we’re only doing half of the job.

The Local: Is that a problem you see a lot — people not knowing how to utilize the resources they have?

BL: I think a lot of people don’t know enough about where to find the best nutrition in the food they buy. A lot of people lack skills in cooking. They haven’t had the opportunity to learn or don’t have the equipment in their home to learn.

The Local: How do you fund your food programs?

BL: We get funding from a variety of source. We don’t spend our health dollars on providing food — we fundraise for that. As a CHC we can get funding through variety of different places so we can offer a greater breadth of programs than traditional health care.

The Local: If you follow the social determinants of health there are issues with transportation, education, housing, legal status. These are huge problems. What is the health system’s role in some of those broader issues that affect health?

BL: It’s shortsighted not to be thinking broadly about what makes people healthy. But that’s not how our health system is designed. Our health system is designed to look after sick people and not think about what made them sick. I think it is more efficient to consider their whole life — and there is movement towards that. Population Health and the recognition of the social determinants are in a lot of strategic plans.

The Local: It really sounds like in order to deal with food insecurity you need to look outside the traditional walls of the health care system. Can you talk about some of the intersectoral partnerships you have?

BL: Everything that we do, we look for partners. We have dozens and dozens of partner agencies from different sectors who are coming here, delivering services, and that’s just the way any CHC would operate.

We partner with Food Share around a number of things. We partner with ESS, a community support agency, for transportation. Our community garden is in a City of Toronto location, so we partner with Parks Toronto to operate. And they fund our balcony gardening program, because a lot of our folks don’t have land.We also run a farmer’s market once a week out of the food bank’s parking lot and give out Market Bucks for clients to spend.

The Local: Do you feel like you take a population health approach?

BL: Absolutely. I mean we are a CHC and part of our model is to take a population health approach. To recognize social determinants of health and to press all of those into everything we do.

So our care doctors don’t just write a prescription; they find out whether somebody can afford to fill that prescription. They ask whether people have done their taxes, because that’s the only way they’re going to get their tax credits.

Everything that we do looks at what we can do to remove barriers to meet the needs in this population.