On the hottest days of the summer, the residents of the St. James Town highrises gather in the lobbies of their buildings. They’re the only tolerable places when temperatures rise. In walkers and wheelchairs, the elderly seek out the coolest spots they can find under the air conditioning vents. Others perch on the few uncomfortable benches and chairs available in the lobby. Most days, there isn’t enough seating for everyone seeking momentary relief. And as night approaches, they’re obliged to return to apartments that won’t cool down for hours, not even after the sun has set.

The highrises of St. James Town are in the northeast corner of Toronto’s downtown core, a community of low-income and racialized people that’s one of the most densely populated neighbourhoods in the country. Most of the buildings were built in the 1960s, and many are not air conditioned. The result is hundreds of apartments unfit for the heat waves of the 21st century: stifling and humid, exacerbating one resident’s asthma, another’s heart condition, threatening to push already precarious health conditions over the edge.

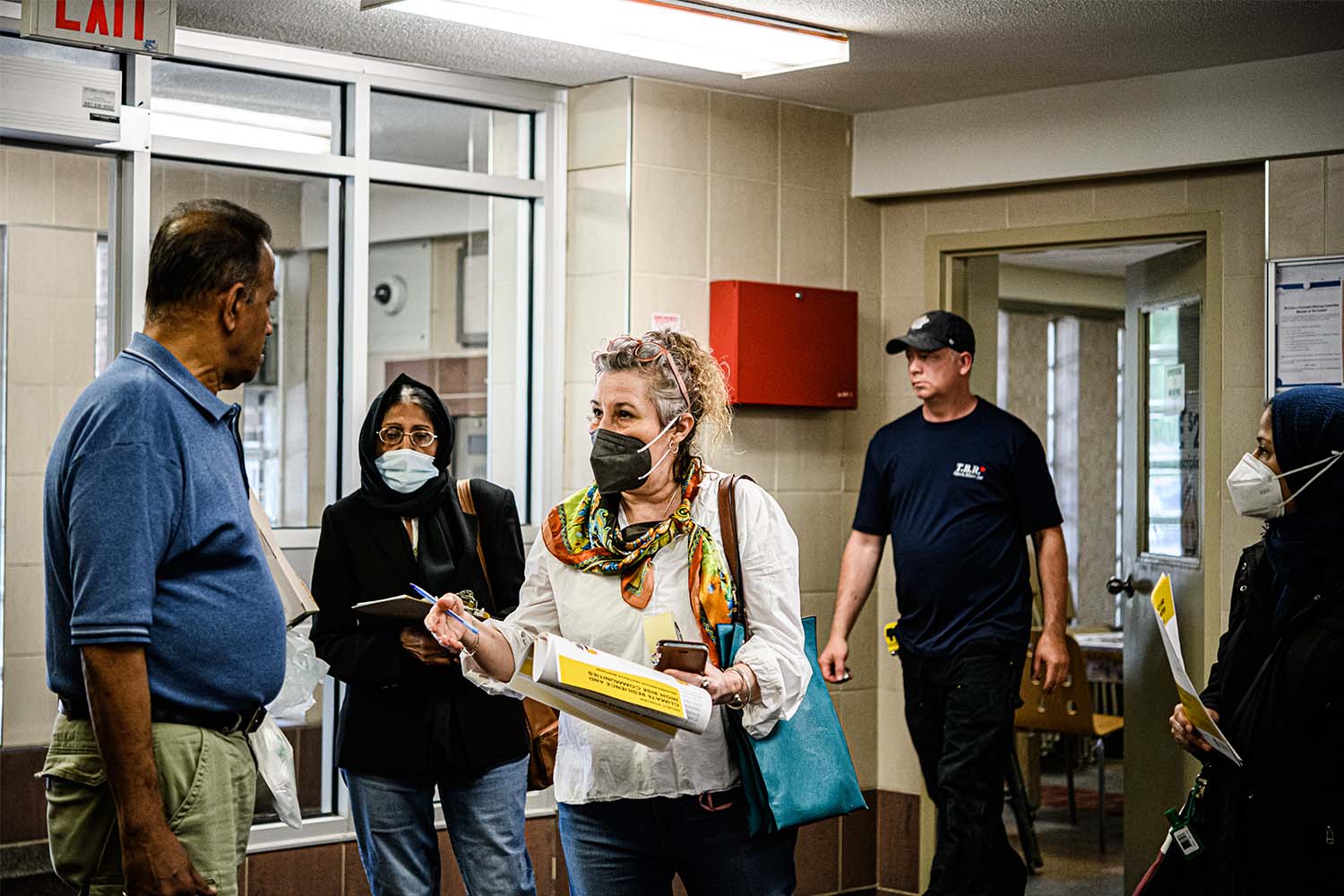

Lidia Ferreira’s responsibility on these days is to check on residents. She works with volunteer-led Community Resilience to Extreme Weather (CREW), an organization that builds and trains networks of community volunteers to respond during extreme weather events. When temperatures rise, Ferreira and her team of volunteers—residents from each floor of a given building—go door-to-door, checking in on neighbours who might be isolated and susceptible to the impacts of heat on the body. For those without air conditioning, they recommend places to go: a local cooling centre, library, community centre, or perhaps the nearest shaded park. Some of these tenants don’t have air conditioning; but in Ferreira’s observation, many of them do, but cannot afford the cost of turning it on.

In the summer of 2019, Ferreira was training volunteers at 77 Howard Street as the region was struck by what a senior climatologist at Environment Canada described as “roasting,” “furnace-like” weather. “I was meeting all these seniors in the building,” says Ferreira, “and it was so sad to see. It was very hot weather, but they didn’t want to use the AC…[they were] so scared about the electricity bill.”

Some residents, Ferreira admits worriedly, don’t have the mobility to go anywhere on their own, nor the will to leave their homes and go somewhere unfamiliar. Many of the tenants in the St. James Town highrises are immigrants, some of whom face language barriers and feel uncertain about their safety. “It’s very difficult for [these particular] people to connect,” says Ferreira. “They were just sitting in their apartment, with nowhere to go.”

When a heat wave hits the city, it doesn’t impact everyone the same way. The residents of St. James Town are exposed and vulnerable to heat every way you look at it. They live in homes with limited or no access to air conditioning, and are at higher risk of the illnesses worst affected by extreme heat, like diabetes or heart disease. They have fewer parks and trees in their neighbourhoods compared to wealthier, whiter communities. They’re more likely to work in hot conditions, like construction or manufacturing, or physically intensive roles that require them to be on their feet all day.

And they’re not alone in their experiences. Across the city, low-income and racialized communities, including in inner-suburban areas like Scarborough, North York, and parts of Etobicoke, are suffering disproportionately during heat waves. While you can’t control when a heat wave will strike, you can control how people experience it. The city has recently instituted policies designed to mitigate the risks of heat, but it is unclear if they can adequately meet the needs of Toronto’s most vulnerable communities. And while the work of people like Ferreira and her volunteers is vital, if Toronto is going to build any form of resilience to the climate crisis, and prevent needless suffering and death, it’ll need to do more than rely on the kindness of neighbours.

Toronto is getting hotter. Even if we envision a future with lower carbon emissions, temperatures in the city are still going to rise. An April report from the University of Waterloo and the Intact Centre on Climate Adaptation projected a dire future. Even in a low-carbon scenario—in which greenhouse gas emissions increase until 2050 and then rapidly decline, one of the four projected scenarios modelled by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC)—Toronto will still experience more than three times as many very hot days (exceeding 30 degrees Celsius) by 2050 as it did in the latter half of the 20th century. In a high-carbon-emissions scenario—in which emissions continue to rise at current rates—the number of hot days could be more than four times that, with 55 days of the year projected to be 30 degrees or more.

In this scenario, the average length of a heat wave will more than double, going up to 8 days. Crops will scorch. Leaves will dry up and fall off trees and bird eggs will cook. Energy grids will likely collapse under the pressure of millions of people blasting their ACs for a week straight, leading to blackouts. Emergency rooms will flood with patients experiencing not only heat exhaustion and illness, but higher rates of self-harm and suicide, which both go up during prolonged periods of heat. Hundreds of people will become ill and die.

Toronto isn’t prepared for today’s heat events, let alone the calamitous future that awaits. At the end of last month, the city saw its first heat event of the season, with temperatures reaching more than 32 degrees on May 31, beating a nearly 80-year temperature record for that month.

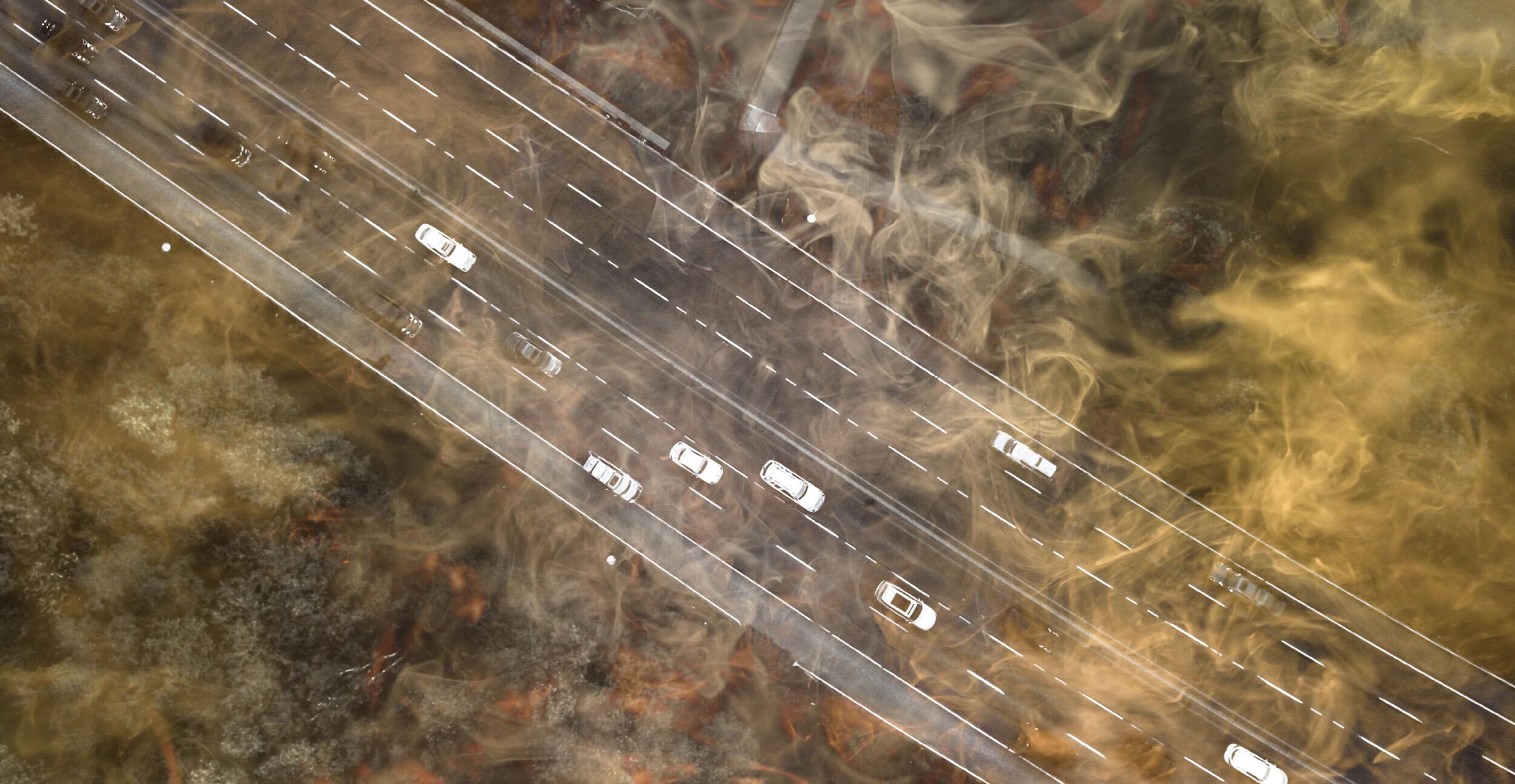

Those temperatures are partly the result of the urban heat island effect, the phenomenon in which urban areas tend to be warmer than rural ones. There are a few major factors that determine how an urban area experiences heat. One is albedo: the ability to reflect sunlight off surfaces like streets and buildings. Dark, asphalt or concrete surfaces absorb sunlight, and thus heat up much quicker and more intensely than light-coloured or reflective surfaces during the summer. Most cities are built almost entirely out of materials with low albedo—think of your average road or highrise—which means during a heat wave they soak in and radiate heat for hours after the sun has set.

Another major factor is the presence of urban vegetation and tree canopies, a natural coolant that provides shade and cools down its surroundings through the release of moisture. Tall urban buildings have proven to be both a blessing and curse: they provide cooling shade to the streets below throughout the day, a temperature difference of up to 25 degrees compared to unshaded areas, but they also retain heat during the day and release it at night, preventing adequate cool-down for its tenants. Add to that the cooling effects of a local water body, and the impact of wind patterns, and you have a city that distributes heat unequally.

While heat waves are becoming more frequent and intense today, Toronto is no stranger to extreme temperatures. The city’s worst-ever heat wave was in July 1936. The weather system swept eastward after decimating the prairies, and for eight straight days Toronto suffered through temperatures in the mid-30s to 40s. Reports at the time described the city’s residents sleeping at the waterfront in the thousands, or in parks and backyards. By the end of the week, more than 200 people had died, mostly children and the elderly—largely from reactions to the heat, but others from drowning in the city’s creeks or in the lake while trying to find momentary relief.

Since then, the nature of how a city responds to a heat wave has changed. Yes, many have gained easy access to air conditioning—but comfort and ease of access to public spaces have gone down. Today, when residents of a city suffer a heat wave, they often do it alone, sequestered to their homes.

Fifty-nine years after the Toronto heat wave, three days of extreme heat devastated Chicago. On July 13, 1995, the temperature in the city rose to more than 50 degrees Celsius with humidity. Emergency operators received more than 16,000 calls that day, 60 percent higher than their average call volume. A power outage on the north side of the city hit more than 49,000 homes, and lasted through the next day and into the weekend, and many of the city’s hospitals stopped taking new patients. People started to check in on their vulnerable or elderly loved ones in their homes, only to find them dead and decomposing in the heat. But the city did nothing: no additional ambulances and paramedics were called in from other cities. Mayor Richard M. Daley seemed to laugh off the crisis during a press conference, saying, “We all have our little problems, but let’s not blow it out of proportion.”

By the end of the heat wave, more than 700 people had died, most of whom were Black, elderly, and living in the city’s poorest neighbourhoods. Elderly Black people died at a rate 1.5 times higher than their white counterparts. The city had to bring in refrigerated trucks to store all the bodies waiting to go to the Medical Examiner’s office.

Years later, when author Eric Klinenberg was interviewed for the release of his book, Heat Wave: A Social Autopsy of Disaster in Chicago, he described the tragedy as a “particle accelerator for the city: it sped up and made visible the hazardous social conditions that are always present but difficult to perceive.”

“Yes, the weather was extreme,” he said. “But the deep sources of the tragedy were the everyday disasters that the city tolerates, takes for granted, or has officially forgotten.”

Last June, it felt a little like the world was ending again, this time in B.C. The heat dome lasted a week, and on its worst day, June 29, temperatures in one small village reached nearly 50 degrees, an all-time record for Canada. Hundreds of people died in the province that day alone, and by the end of the week, the heat had led to more than 600 deaths. In Vancouver, lower-income neighbourhoods that are home to racialized communities reported rates of emergency room visits two to three times that of wealthier, whiter neighbourhoods. The B.C. coroner’s recent report on the impacts of the heat dome didn’t break down deaths by race or ethnicity, but did find that nearly half of all the victims of the heat dome were living in socially and materially deprived areas.

In Toronto, it’s not a question of whether such a disaster will strike, but when. This city, like all others, isn’t built equally for all residents, and that will dictate how the crisis unfolds. A 2017 study of urban tree cover from Toronto Metropolitan University found that higher-income and whiter neighbourhoods had a far higher number of trees than lower-income and racialized areas. Before that, research found that Toronto’s industrial and commercial areas—most commonly found in the inner suburbs—had higher ambient temperatures than parkland and the waterfront. And in 2016, research showed that parts of Toronto with less than five percent tree cover had five times as many heat-related ambulance calls during extreme heat events as those with more than five percent tree cover.

Heat affects the body in two ways. With the direct effects—heat exhaustion or heat stroke—a person’s core temperature goes up while their body struggles to self-regulate and cool down. If drawn out over multiple days and nights, muscles begin to cramp and break down, and organs shut down. When the effects are indirect, however, it’s much harder to demarcate where the impacts of heat begin and end. The most affected are young children, the elderly, and people with chronic conditions—especially diabetes, asthma, and heart or lung conditions. Research on Ontario hospitalization and death rates during heat waves found that hot weather led to a 30 percent increase in hospitalizations for diabetes-related concerns, and raised rates of deaths relating to respiratory or heart issues by five percent for every 5 degree increase in daily temperature.

For people with mental health conditions like schizophrenia, symptoms are worsened, sometimes to the point of requiring hospitalization or being fatal. Death rates among those accessing mental health services are higher during hot weather than for people who don’t, in part because a side effect of some psychiatric medication is a decreased ability to self-regulate one’s body temperature; rates of suicide also rise.

“There’s one patient that always comes to mind when people ask me about the heat,” says Dr. Samantha Green. She’s seen these health crises play out during heat waves in her work as a family doctor in St. James Town, Regent Park, and Moss Park, and in her capacity as a faculty lead in Climate Change and Health at the University of Toronto.

“He’s older, in his 60s, has asthma. He has some kids who live out in the suburbs, and they’re really not very close. He didn’t have an air conditioner for a long time…[and] for several years in a row, every summer, I would worry that he would die alone in his hot apartment during an extreme heat alert—not having access to adequate cooling facilities, maybe with an asthma exacerbation. And no one would know.”

Green ultimately helped advocate for her patient to get the money he needed to get an air conditioner through the Ontario Disability Support Program, which provides funding if the applicant can provide a doctor’s note stating medical necessity. But that won’t address the living conditions of the thousands of seniors in similar circumstances who don’t have anyone to advocate for them. And it doesn’t begin to address the needs of people who are unhoused, who Green points out are more likely to have chronic conditions, or people who are exposed to heat in their working conditions, like factory or construction workers, people who work outdoors, or even healthcare professionals working in institutions that don’t have AC.

If we’re not able to support people today, Green worries, we’re nowhere near ready to meet a future of rising temperatures and more frequent heat waves. “We’re just not prepared,” she says. “There’s also a very scary risk of experiencing a heat wave compounded by an electrical outage, with increased energy demands during a heat wave. The mortality that could result from such an event—I don’t even want to think about it.”

For Nick Puopolo, the sheer scale of the health risks dawned on him in 2020, when he visited his elderly mother at her long-term care home during a heat wave. His mother, Saveria, now 87 years old, has lived at Woodbridge Vista, a northwest Toronto LTC home run by Sienna Senior Living, for about six years. On a visit two summers ago, Puopolo noticed that the thermostat in the hallway near the nurses’ station read 26 degrees. So he bought a portable thermostat and brought it to his mother’s room, where the screen confirmed his suspicions—it was even hotter in the residents’ rooms than in the hallways, which were already verging on unbearable. His mother’s room—where she spent almost all her time, bedridden and dealing with existing heart health concerns—was 28 degrees. The humidity was 47 percent.

He worried the heat would kill her and the other residents at the home. “I don’t know of anybody that’s living in these long-term care homes that don’t have [high-risk] medical conditions,” he says. “They’re laying there, they can’t really get up, they can’t ask for water…there’s not enough staff that continue to go into the room, sit with them, make sure they drink their water, put a cool towel on them.”

Many of the residents, Puopolo adds, don’t have family members who can regularly come in and check on them. Those who are bedridden can’t access the cooling rooms—communal spaces in LTC homes that are required to have air conditioning. Last year, when the province announced that 100 percent of LTC homes have air conditioning, they were referring to these communal spaces—a piecemeal solution Puopolo feels the provincial government and LTC companies came up with just to say they’d done something to address the issue.

As of last year, 40 percent of LTC homes in Ontario were yet to implement air conditioning in residents’ rooms. The older homes cite the fact that they weren’t built with the structural capacity to have air conditioning in every room. Solving the problem requires retrofitting, something Puopolo advocated for two summers in a row before Sienna implemented a permanent solution in his mother’s home. However, Puopolo says, the LTC company has ignored his calls to install air conditioning in their other homes, where many residents still suffer during heat waves. “You know, if there isn’t someone watching over them and embarrassing them, they won’t do anything,” he says. (Sienna told The Local their plan to install AC in all residents’ rooms is underway, and state they’ve invested $600 million in the redevelopment initiative.)

It’s impossible to know exactly how many deaths in the province or the city are caused by extreme heat. That’s because people don’t necessarily die from heat; they die from health conditions exacerbated by it. In 2011, Toronto Public Health and Environment Canada estimated that heat leads to an average of 120 premature deaths in the city every year, a number that will only grow as the crisis worsens. More recent provincial estimates link a 5 degree rise in the temperature with a 2.5 percent increase in the death rate, or around 4 excess deaths a day. But those are estimates, not a precise answer, even though that feels like the most valuable tool we could have.

Last year, the Canadian Environmental Law Association, Advocacy Centre for the Elderly, the Advocacy Centre for Tenants Ontario, and the Low Income Energy Network came together to call on the province to better track premature deaths caused by heat, pointing to the differences between how Ontario tracks heat deaths compared to Quebec and B.C. When the 2018 heat wave hit Montreal, the city reported that at least 66 people had died as a result. Last year, the B.C. coroner’s office reported that 619 people died that summer from heat-related causes, more than a third of whom died in a single day during the heat dome. The Ontario coroner does investigate direct heat deaths, like from heat stroke for example—but that number is relatively minimal, with just three investigations reported in 2018. The much bigger issue—the impact of heat on existing chronic illnesses among vulnerable patients—went uncounted.

Ontario’s chief coroner, Dr. Dirk Huyer, understands the desire to quantify the problem—but “there’s no scientific way for us to answer that question,” he says. When heat exacerbates the conditions that lead to a person’s death, he explains, it’s hard to say to what degree. “The autopsy won’t answer the question, the coroner’s office can’t specifically answer the question, the doctors can’t specifically answer the question…I think we would be unfairly providing information that may not be accurate.”

For a death to be investigated, it needs to be reported to the coroner’s office by the point of contact who determines the initial cause of death. If an elderly person with chronic illnesses dies of a heart attack in an Ontario LTC home during a heat wave, for example, that would be considered a natural death, and not something to be reported for investigation.

Montreal has a system in which they note when a person has died in hot conditions—and when that’s the case, they say it may have been a heat related death. “They go broad, as opposed to us—we go more narrow on the reporting process,” Huyer says.

In the case of an extraordinary event like B.C.’s 2021 heat dome, Huyer explains, the Ontario coroner would begin an investigation. But during the growing number of “normal” heat waves in this province, the deaths of individuals indirectly affected by the heat remain uncounted.

“Yes, counting is important—but we want to make sure there’s nothing to count, if we can,” says Huyer. “Everything should be focused on prevention.”

For advocates, however, the province’s tracking model is holding us back from knowing the scale of the crisis and acting accordingly. “We’re radically undercounting the impact of the climate crisis and extreme heat on people in Ontario,” says Jacqueline Wilson, a lawyer at the Canadian Environmental Law Association. “We’re not getting a clear picture right now.”

As the climate crisis worsens, catastrophic events like the heat dome will become more common, and the need to know the scale of the damage will grow in equal measure. And if prevention is the priority, the city and the province need to start developing heat resiliency now.

The first and most obvious solution is access to air conditioning, a resource that right now is only available to those who can afford it. Provide access to cooling where people are, rather than making the residents congregate outside their homes at cooling stations. Put ACs in LTC homes, in community housing, make it accessible for low-income tenants.

Toronto bylaws dictate that if a building has air conditioning, it needs to be on between June 2 and September 14. But advocates argue for a maximum temperature, similar to the minimum temperature of 21 degrees in the winter, that would provide rights to tenants without existing ACs. At what point should it become the responsibility of landlords to provide AC where there is none?

The city says there are massive hurdles to implementing these kinds of changes. Mandating air conditioning would involve changes to the Ontario Building Code, a decision that can’t be made at the city level. And a mandatory maximum temperature in residences has been deemed largely unfeasible by Toronto Public Health given it would require extensive retrofitting to buildings without AC (which come with potential rent increases) and the fact that the city’s energy grid may not be able to keep up with demand.

This year, the city started a program to provide financing to owners to retrofit older buildings above three stories, with the mandate that the landlords cannot apply for rent increases for the improvements above the province’s guideline. That’s a crucial step in making sure the housing remains affordable to the current residents, but it’s also one of the drivers that might push landlords to pursue private funding that will allow them to raise rents. Leaving the responsibility of making improvements to landlords alone is dangerous—without firmer and more urgent policy mandating improvements in the worst-hit buildings and neighbourhoods, starting perhaps with Toronto’s own community housing stock, the city is leaving its vulnerable, low-income residents to suffer the heat indefinitely.

Providing air conditioning, however, is just the first battle in a much longer war.

“In Toronto, we are in a more urgent crisis than in other places,” says Umberto Berardi, the Canada Research Chair in Building Science and a leading researcher on Toronto’s urban heat island effect.

“[We need] more resiliency in the sense of passive design and urban design that doesn’t really force our buildings to rely on air conditioning systems all the time. At the end of the day, air conditioning is yet another social dividing factor, because of energy poverty.”

Most of the new buildings coming up in the city are designed with unnecessary amounts of glass, which trap massive quantities of heat. “You see this in the amount of hours we use air conditioning systems in Toronto,” says Berardi. “Climate change, heat waves, and then glass: these three factors basically mean current buildings run air conditioning systems for four months [a year], whereas 40 years ago, there was probably no residential building [doing so].”

“It’s not just a matter of the environmental implication, it’s also a matter of the economic implications. People cannot necessarily afford all the costs that we are going to suffer moving forward.”

Passive cooling techniques can include cross-ventilation within apartments and across the building, using light colours in building materials so that buildings reflect sunlight rather than absorb it—think of the white walls of Santorini, Greece, Berardi says—or planting green roofs and significantly increasing tree cover, especially in those neighbourhoods deprived of it. These solutions are within reach, and will make a material difference to living conditions.

In 2010, the city began implementing the Toronto Green Standard for new builds, which sets out both mandatory and voluntary guidelines to build energy-efficient structures that mitigate urban heat island effect. The standards are a move in the right direction: they require 50-75 percent of the building’s hardscapes, including walkways and driveways, courtyards or surfaces, to be built with high-albedo materials that reflect sunlight and heat. They include mandates on green roofs and requirements about planting trees around new builds and in parking areas.

“By introducing the Toronto Green Standard we have implemented among the most aggressive requirements for new construction,” said a spokesperson from the Mayor’s office, more broadly pointing to the city’s plan for tackling climate change, TransformTO.

“That’s a really good framework to use,” says Robin Buxton Potts, city councillor for Toronto Centre, where St. James Town is located. “But I think that we have also seen that kind of work has been significantly underfunded in the city of Toronto over the last couple of years…Escalating the funding and the timeline on the TransformTO plan is the best thing that we could do.”

“While we [institute long-term plans], we also need to look at the more comprehensive, immediate solutions,” she adds. “Having more cooling centres that are closer to people’s homes would definitely help…but those aren’t necessarily in the middle of highrise neighborhoods like St. James Town. So how can we better prioritize where some of those cooling centres go, and make them more accessible?”

The volunteers in St. James Town are wondering the same thing as they prepare for another hot summer. Lidia Ferreira sees the notices in the lobbies of the buildings recommending that on hot days residents visit community centres 30 minutes away on foot—advice that most of the people she checks in on can’t possibly follow. Instead, her team has taken to leading community walks for the highrise residents. What started as groups of seven or eight tenants escaping the heat by walking through local parks has now turned into groups of 15 or even 30. Residents of all ages and walks of life join in: mothers bringing their young children, older neighbours arriving alone, looking not only for relief from the heat but also connection and community.

When the walks were first proposed, the lack of parks in St. James Town meant the nearest green space was the St. James cemetery, an idea some residents quickly turned down. Now they leave the neighbourhood entirely. The towers recede behind them, taking on the glaring sunlight and heat, as they walk to Rosedale, the leafy neighbourhood to the northeast filled with parks, sturdy old-growth trees, and a ravine that skirts the Don River—a place that is beautiful, wealthy, and cool.

Correction—June 27, 2022: The Low Income Energy Network was added to the list of organizations asking the province to track heat as a cause of death.