It was three o’clock in the morning when John Campbell first felt the bites. Later, in the light of day, he saw them on his sheets: “They were these wee brown things, and when I squished one between my fingers it was filled with blood,” recalls Campbell. He had bedbugs.

This was in October 2016. And 10 months later, in August 2017, Campbell says he still hasn’t been able to get a solid night’s sleep. “My sleeping patterns went down the tube,” he says. “After a few days, I didn’t know if I was being bitten or if it was just my imagination running wild.” Even after replacing his mattress and bedding and undergoing multiple pest control treatments, Campbell says he still thinks about the bugs and starts to feel bites every time he lies down.

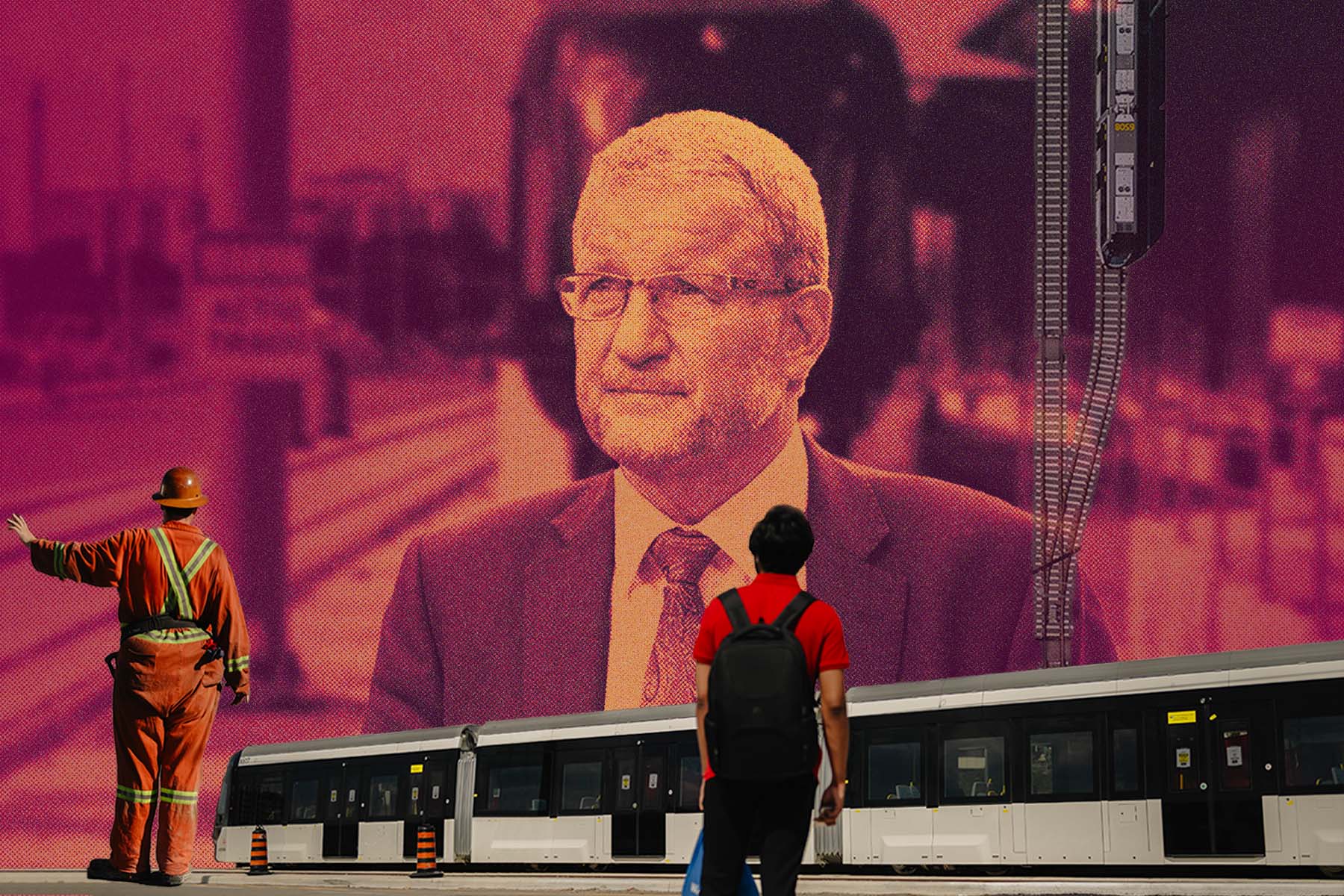

Campbell lives alone in a Toronto Community Housing building in the Mount Pleasant West neighbourhood, near Yonge and Eglinton. Campbell isn’t his real name. He asked The Local to use a pseudonym because he knows there’s a stigma around bedbugs and he doesn’t want his neighbours to assume he’s not taking care of his apartment. A retired typesetter who can still read upside down and backwards without a second thought, he has a full head of thick white hair and a mischievous grin that appears whenever he knows he’s about to land a joke. Campbell likes to ask people he meets to guess his age. Just about everyone gets it wrong, placing him somewhere in his early 70s. In fact, he turned 87 this year.

Campbell has lived in the same one-bedroom apartment for more than 20 years. Last October was the first time he had seen a bedbug. For seniors like Campbell, who live alone and who have reduced mobility and other health challenges, getting rid of bedbugs can be a nearly impossible task. The many steps required to make sure pesticide treatments work effectively can be difficult to manage on their own. And if the bugs aren’t eradicated completely, repeated or prolonged infestations can have serious impacts on seniors’ physical and mental health.

Samuel Leite is the manager of community care at SPRINT Senior Care, a not-for-profit community support service agency that provides assistance to seniors living at home in Mount Pleasant West and surrounding neighbourhoods. He says that although bedbugs are not technically deemed a health hazard (the bites themselves are a nuisance, but not dangerous), as a social worker providing care to seniors, he has seen firsthand just how devastating an infestation can be. “Bedbugs carry a strong social stigma and can result in stress, anxiety, sleeplessness and further social isolation, all of which compromise the client’s health and wellbeing,” says Leite.

He has seen cases among his clients where the loss of sleep caused by bedbugs has led to severe mental distress and even physical pain. Clients with mental health issues become even more socially isolated when they have to deal with the added stigma of bedbugs, which means they may not make it to doctors’ appointments or may start avoiding going out at all. Leite had one client who developed such severe paranoia during persistent and repeated infestations that she stopped sleeping on her bed and threw away almost everything in her apartment. She kept a straight-backed dining room chair without armrests. After several nights spent trying to sleep on the chair she developed debilitating neck and back pain.

In a city with a rapidly aging population, many seniors are now facing challenges the health care and social services systems haven’t foreseen and are not yet equipped to handle. For seniors, something as mundane as a bedbug infestation, which might once have been considered a minor public health issue, can quickly snowball into a costly and traumatic ordeal. This is especially true for seniors living alone, who may already be dealing with health impacts related to social isolation.

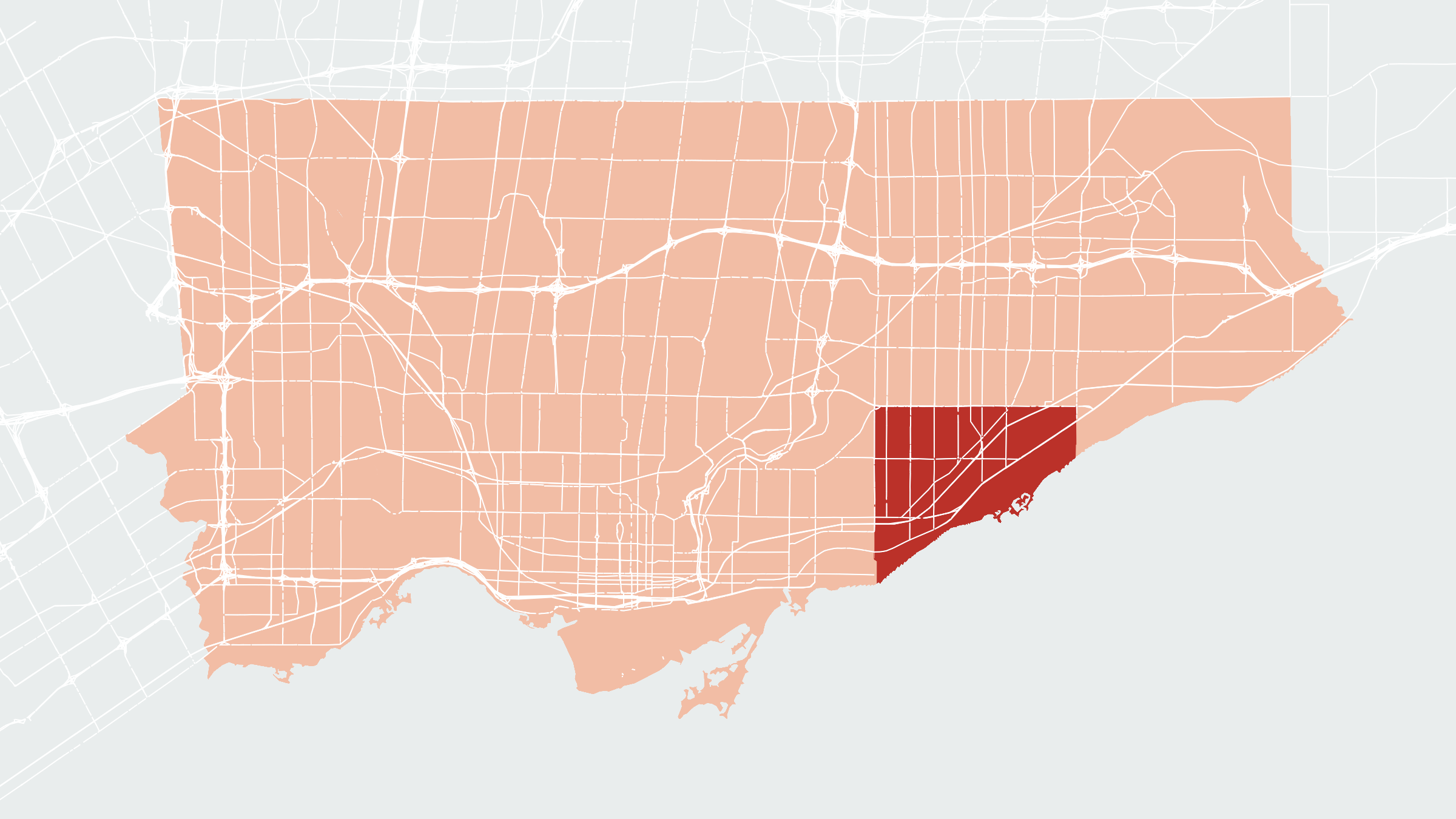

In Mount Pleasant West, like in the majority of Toronto neighbourhoods, the percentage of the total population that are 65 and older is increasing. According to census data, there were 28 percent more seniors living in Mount Pleasant West in 2011 than in 2006. And there are more seniors living alone there than in any other neighbourhood. In 2011, there were 1,915 adults aged 65 and older living alone in Mount Pleasant West, which represented more than half of all seniors in the neighourhood.

In a city with a rapidly aging population, many seniors are now facing challenges the healthcare and social services systems haven’t foreseen and are not yet equipped to handle.

Leite says bedbugs are “a very prevalent issue” among the clients SPRINT Senior Care serves in Mount Pleasant West and surrounding neighbourhoods. He estimates that working with clients who are dealing with bedbugs and other infestations makes up about 25 percent of social workers’ caseloads. In addition to dealing with the stress and social stigma of the infestation itself, Leite says, many seniors are overwhelmed by the extensive cleaning and preparation that is required to make sure professional bedbug treatments are effective.

When Campbell reported the bedbugs to Toronto Community Housing (TCH), he received a standard 26-item checklist to prepare his apartment for the pesticide treatment. Among the tasks on the list: washing and drying on high heat all bed linens and clothing, pulling all furniture 12 inches away from the wall, emptying and removing dresser drawers, and placing all household items in sealed plastic bags and containers. Next is the extermination protocol, which consists of two treatments, two weeks apart, and then a follow-up inspection to make sure no new eggs have hatched. This means tenants are supposed to live with everything in bags and boxes for at least four weeks to avoid letting the bedbugs get re-established.

Leite was Campbell’s social worker at the time, and he sat down with him to make a plan. Since Campbell didn’t have family members who could help, Leite gave Campbell information about a cleaning service and encouraged him to hire help. But it was a paid service (bedbug prep services can run anywhere from $200-$1000, depending on the state of the unit), and he was also looking at having to pay to replace some furniture and household items. So, he decided he would try to do it on his own. Campbell has high blood pressure, some breathing difficulties, and chronic conditions in his legs and feet that have forced him to start using a cane. “I’m shuffling around like an old man now, but I’m stronger than I look,” he says. “And what choice did I have?”

Campbell got rid of his mattress and box-spring, which he’d purchased less than two years earlier, and replaced them with new ones with sealed plastic covers. He washed and dried all his clothes and towels, but opted to throw away his bedding rather than haul it down to the laundry room and back, a trip that involves holding onto the hallway wall for support, hooking his cane through the handle of his laundry basket and dragging it a few feet behind him as he walks. He then had to make four separate trips on foot to buy four large plastic bins with lids. He says even carrying one large bin at a time in one hand while walking with his cane was a challenge, especially when it came to climbing the set of stairs between the sidewalk and the front doors of his building.

Leite says there are not currently any free bedbug prep resources available to seniors like Campbell. The intensive, time-consuming prep services are beyond the scope of what a social worker can do with a client. And he says even when seniors qualify for in-home supports provided by Home and Community Care Toronto Central LHIN or the City of Toronto, in his experience the agencies that deliver the services will often pull out when an infestation is confirmed due to health and safety concerns for their workers.

Richard Grotsch, the senior manager of Environmental Health at Toronto Community Housing also tries to assist TCH tenants who are unable to do the bedbug treatment preparations on their own. “I or someone from my team will go out to the unit and assess what can be done, and we will try to link them to whatever resources are available,” says Grotsch. According to TCH’s 2016 annual report, it helped connect tenants with $265,000 in external funding to support managing pests or other complicated unit conditions (this also includes tenants who were connected with “extreme cleaning” or other decluttering or hoarding support programs). And TCH has a partnership with Toronto Public Health to help the most vulnerable seniors to subsidize at least part of the cost. But even that funding is only available for preparations before the first spray, and there is nothing to help seniors maintain the state of their homes between treatments or to put everything back after the bugs are gone.

Leite says a significant proportion of SPRINT Senior Care’s clients are living with dementia. For those who are socially isolated, without a family member who can remind them not to unpack their belongings in between sprays or offer them a place to store some bags and bins, it can often take multiple rounds of treatments over the course of several months before bedbugs are completely eradicated. When bedbug infestations are prolonged, seniors’ health starts to decline.

“If someone had been going out of their way to make life miserable for me, they couldn’t have done a better job of it.”

Campbell’s apartment was deemed clear of bedbugs after two treatments, but he doesn’t recall getting the “all clear” from the pest control company. Despite Leite’s repeated assurances that he could unpack, Campbell still isn’t convinced it’s completely safe to take everything out of his plastic bins. And after nights spent lying awake in bed trying not to think about the bugs, he wakes up groggy. “I’m not as sharp mentally as I used to be,” he says.

Campbell is currently on a waitlist to get into a more accessible building — one that doesn’t have stairs out front so he can come and go more easily with his shopping buggy now that he’s using a cane. He was recently offered an apartment in a building not far from his current address, but after a social worker at the hospital warned him it was known for bedbug infestations, he turned it down. Campbell says he’d rather wait than risk another bedbug ordeal. “I mean if someone had been going out of their way to make life miserable for me, they couldn’t have done a better job of it,” he says. “I don’t want to start that all over again.”