“When I worked through SARS here in Toronto, I kept every piece of paper that I got. Either The Toronto Star when they took out the full-page ad, The Globe and Mail when they thanked us, the hospitals that I worked at would send out memos—I kept every single one of them, because I was very, very proud of that,” says Blake, a long-term care worker. “But I don’t feel proud of this.”

Blake is witnessing a disaster unfold in real time. (Blake has been given a pseudonym and details of his role have been concealed in order to protect his identity, for fear of reprisal). He works in a supervisory capacity at a subsidiary of Extendicare, a Toronto Stock Exchange-traded company and one of the largest owners of long-term care homes in Canada, with close to 60 facilities across the country. Less known is Extendicare’s contract services business, Extendicare Assist, which manages homes on behalf of other owners, including the two homes in Ontario that have seen the most deaths from COVID-19—Tendercare, with 73 deaths, and Orchard Villa, with 70 deaths.

Extendicare Assist is the largest outsourcing operation in Ontario. It has contracts with 44 long-term care homes across the province—almost half of all Ontario’s outsourced facilities. It is also the operator with the worst mortality rates during a pandemic that has devastated long-term care homes across the province.

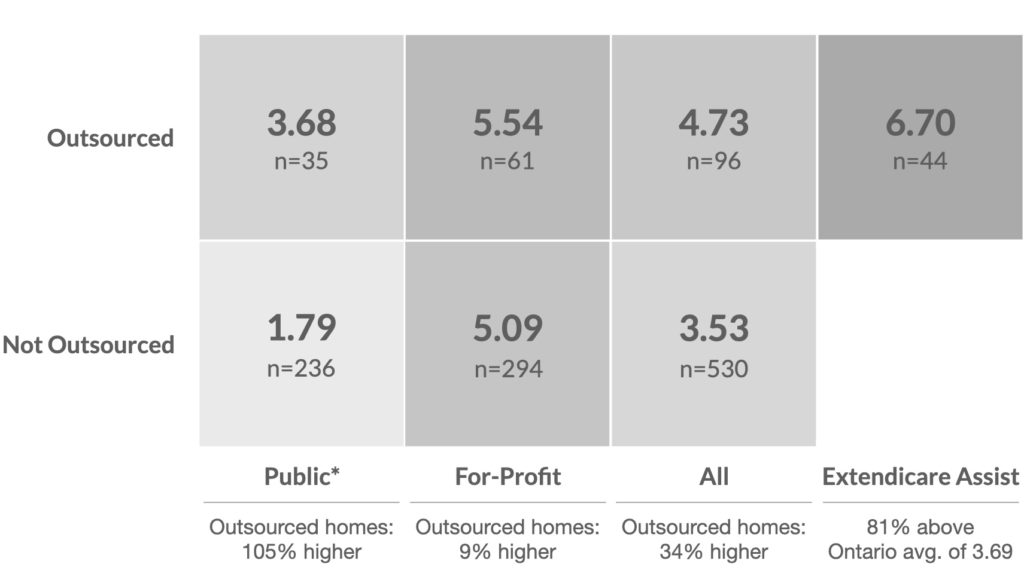

The Local has now found, through analysis of government data and information available on Extendicare’s website, that the COVID-19 death rate across all Extendicare Assist locations is 81 percent higher than the industry average: 6.70 deaths per 100 beds, as opposed to the Ontario average of 3.69.

For Blake, the horrific death rates seen at Extendicare-managed facilities weigh heavily. Having worked as a nurse for three decades, he now works in a support role that involves visiting some of the facilities run by Extendicare—a role he was initially hesitant to take on, knowing he had an elderly parent to look after.

“At the time we got called up to do this, it was much like your nursing career [has] come to fruition, and you think you’re being called out for some big noble thing,” he says.

But, he continues, the realities on the ground are more like a warzone, and the bureaucratic environment is “overwhelmingly a mess.”

Blake has been to five long-term care homes to provide support services to the staff since COVID-19 began. The names of the homes are being withheld to protect his identity. Extendicare managed three of the homes, and owns the other two. Blake describes witnessing breakdowns in communication between Extendicare and the owners of the facilities, high rates of turnover amongst a workforce that is overworked and understaffed, dangerously lax PPE practices, and a lack of leadership from Extendicare.

His experiences are reflected in the Ministry of Long-Term Care inspection reports coming out of the five facilities since the start of the pandemic. A majority of the written notifications issued are regarding a failure of staff and Directors at the facilities to communicate things like medical treatment plans within their own teams or to Ministry leadership. But this lack of communication has material consequences: one report stated that team members failed to collaborate in their approach to a resident’s care, which ultimately compromised the quality of that care—the resident’s food intake declined, as did their health, and staff failed to adequately consult a dietician prior to the resident’s death.

The staff and management Blake encountered at the facilities “don’t seem to have a real clear idea of what they’re doing or what we’re supposed to be doing there. The enforcement of PPE, the screening processes, they all sort of went by the wayside.”

His observations are consistent with those reported by doctors elsewhere.

When asked for comment, Extendicare said in a statement that, “we must be explicitly clear that we find these categorizations wildly inaccurate.”

“Any insinuation that Extendicare has not responded with every available resource to combat this virus is not true.”

“The long-term care sector has faced extreme staffing challenges for years, an issue that has been exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic. […] When team members become sick and have to isolate, the options to maintain staffing levels include bringing in personnel from staffing agencies, pulling staff from other long-term care homes or pulling staff from hospital partners,” the statement read. “Extendicare, along with many other operators and the OLTCA, have called for the province to recruit more well-trained and well-compensated health care workers to better support delivery of care in Ontario’s long-term care homes.”

When asked about staff testing in their facilities, Extendicare said that they implemented weekly staff testing in June, and “received an enthusiastic response from our teams without needing to mandate participation.”

Canada does have a documented registered nurse shortage, which was a concern before the pandemic began and left more staff incapacitated due to illness. Blake, and family members of Extendicare-managed home residents, allege that cost-cutting measures have exacerbated the existing shortage, and brought us to this point in the crisis.

“The people that work on the frontlines […] they’re lovely,” he says. “And they’ve been left to hang—they’ve been exposed to this thing because of people who are too busy trying to cut back on, ‘Oh, what, three baths a week? Let’s give you two.’”

In fact, one home he visited was given a written notification from the Ministry after an inspection revealed short-staffing had led to a failure to bathe residents as required.

After dedicating his life to nursing, he has lost trust in his employer. “There is no friggin’ way I would ever put [my mother] in a place like that. Never.”

Much has been written about the disparity between private and public long-term care homes during this crisis. But the role of outsourcing has gone largely unexamined.

Ontario’s long-term care industry has traditionally been segmented along ownership lines: for-profit, non-profit and municipal. The prevailing view, backed by ample research, is that quality of care is highest in municipal homes and lowest in for-profit homes.

However, this view of the industry is overly simplistic and assumes that owners are operators, which is increasingly not the case. Analysis by The Local reveals that 96 of Ontario’s 626 long-term care homes have been outsourced, where the owner of the license has contracted a third party to operate the home. As of publication date, there have been at least 506 COVID-19 deaths in outsourced homes. That’s a rate 34 percent higher than homes that have not been outsourced.

Outsourcing is most prevalent among for-profit homes, but it happens across the industry: of the outsourced homes, 61 are for-profit, 30 are non-profit, and 5 are municipal. Non-profit and municipal homes as a whole have performed relatively well compared to their for-profit counterparts during the pandemic. However, The Local’s analysis shows that non-profit and municipal homes that have outsourced their operations had death rates that were 105 percent higher (3.68 per 100 beds) than non-profit and municipal homes that did not (1.79 deaths per 100 beds). Clearly, outsourcing blurs the lines separating for-profit, non-profit and municipal homes. It’s not enough to ask who owns the home; it’s also a question of who operates it.

COVID-19 Deaths per 100 Beds, by LTC Home Types in Ontario

Source: Government of Ontario data. Extendicare Assist affiliation obtained from company website and verified through communication with company. Data as of January 12, 2021. *Public includes non-profit and municipal homes.

Responding to The Local’s data findings on mortality rates in facilities run by Extendicare Assist, Extendicare stated that “the worst outbreaks are the result of a combination of factors, like the timing of the outbreak, age of a home, rate of community spread, impact to staff and ability of others in the health system to step in with support. These issues cannot be identified in a per-bed analysis.”

They continued: “Third-party expert research by the Registered Nurses Association of Ontario, the Ontario Long-Term Care Association (OLTCA) and other experts in the medical community shows that a long-term care home’s age, size and proximity to community spread are the causative predictors of a severe outbreak, not who owns the home.”

A recent research study published by Nathan Stall and colleagues in the Canadian Medical Association Journal showed that for-profit status is associated with an increased number of COVID-19 deaths in long-term care, but that is largely due to the fact that for-profit homes tend to be older facilities. These older homes, which are typically based on 1972 design standards (also known as “C beds”), have smaller room sizes, more residents per room, and shared amenities, and therefore pose greater challenges for infection control and prevention.

Extendicare’s argument suggests that the homes owned by Extendicare Assist’s clients are older and therefore the high death rates are inevitable. The Local compared C beds operated by Extendicare Assist to those owned by Extendicare itself and found that the death rate is 80 percent higher for Extendicare Assist-managed C beds (9.08 vs 5.04 deaths per 100 beds). This apples-to-apples comparison shows that the age of the home matters, but outsourcing seems to matter even more. The Local asked Extendicare if there are differences in staffing or infection prevention and control practices between Extendicare Assist versus Extendicare-owned homes that could perhaps explain this difference. Extendicare did not provide a direct answer to this question.

Extendicare’s contract services business (which includes Extendicare Assist and its group purchasing division) is lucrative, with a profit margin of 56 percent in 2019, the highest among the company’s many business lines. These services generated $24 million in annual revenues.

This might not seem much considering that the homes contracting with Extendicare collectively provide over $330 million in government-funded care annually. The reason for this is that when a home contracts with Extendicare, it doesn’t necessarily hand over the entire budget—just the parts necessary for Extendicare to become the brains of the operation. In many cases, this means employing the executive director and other management positions, setting policies, and managing budgets and staffing. The majority of the home’s workers, and therefore budget, remain on the owner’s payroll.

It’s difficult to understand how the outsourcing crisis has reached this stage given Extendicare’s lack of transparency regarding their subsidiaries’ responsibilities within each home they service. The menu of services on offer is wide-ranging, from clinical care to financial services, purchasing, and capital planning. “Our resources help you provide care and services to those who depend on you, while maintaining a close eye on your bottom line,” says Extendicare Assist’s webpage.

Long-term care homes don’t always disclose their relationship with Extendicare on their websites, and when they do, the amount of detail they provide is up to their own discretion— leaving families confused about what they’re paying for.

Extendicare said in a statement that, “While the scope of our contracts with Assist clients are tailored to suit each partner, we do all we can to support them, or facilitate support from others in the health care system.”

The lack of transparency is one of the most significant frustrations for family members of residents inside Extendicare-managed facilities. Even before COVID-19 began, many families encountered extreme staff turnover and shortages, mismanagement of food provision, and a lack of resources available to residents—resources many say were guaranteed to their family members when they moved in.

“They have this horrific situation where every week I go in, they would have a different group of PSWs,” says James Ha, the son of a Tendercare resident, whose troubles with Extendicare started two years before the pandemic. “It is the most infuriating thing because how can you possibly provide service when the entire work crew—well, they do keep the nurse—but everyone else has changed?”

Tendercare, a Scarborough long-term care home formerly managed by Extendicare, is currently the worst-hit long-term care home in the province. The home was taken over by North York General Hospital on Christmas day.

Dr. Silvy Mathew, who visited the home at the height of the crisis just before the takeover, describes seeing the patients get progressively weaker, more ill, and less able to communicate, while staff tried their best to manage the growing crisis.

“They’re just lying there staring at you or sleeping, […] they’re so helpless,” she says. “It’s not imagery that you want to envision for any loved one.”

Ha’s father, Thanh Kim Ha, moved to Tendercare in April 2018, after Ha’s mother had a kidney transplant that left her weak and unable to look after her husband. It was a battle from the very beginning. The Local has obtained copies of emails from Ha to Tendercare managers containing weekly complaints on behalf of his father, who is immobile and unable to verbally communicate. Ultimately, despite her own health concerns, Ha’s mother started visiting Tendercare every day to make sure his father was eating at least one meal.

“They have one [staff member] going around feeding 10 people in the hour of the feeding, and so each person gets about six minutes. So basically when they go in, they would just shove the spoon into their mouth, and half [..] of it will go on the bib,” Ha alleges. “My mother was so livid.”

Despite what she saw, Ha’s mother asked her children not to complain too much, fearing Thanh would face the repercussions. But with circumstances rapidly devolving, Ha didn’t have a choice.

“I continue to be extremely concerned about my father’s weight loss,” reads a June 2018 email from Ha to Tendercare managers, three months into his father’s stay at Tendercare. “Losing 5kg in 5 weeks for a healthy person is concerning, but for a senior his age it is dangerous.”

Ha claims gaps in his father’s physiotherapy and doctor’s appointments, as well; Thanh needs 15 minutes of physiotherapy a day, he says, but “they would go weeks without doing anything with him.”

Outsourcing blurs the lines separating for-profit, non-profit and municipal homes. It’s not enough to ask who owns the home; it’s also a question of who operates it.

When COVID-19 struck, Ha recalls having no idea what Tendercare was planning to do. It was only in December that regular updates began.

On December 8, Tendercare experienced its first COVID-19 case among residents. Within a week, cases had climbed to 92, with 7 deaths. This prompted the province to send in an inspector on December 16. Infection prevention and control practices were found to be so lacking that the home failed to comply with ministry regulations. The next day, an order was issued requiring Tendercare to provide leadership, monitoring, and supervision, as well as education and training in infection control to staff. It was also ordered to keep PPE supplies stocked.

When North York General Hospital took over operations at Tendercare, there had been 121 resident cases and 49 staff cases of COVID-19 in the 256-bed home, as well as 31 deaths. It wasn’t the only Extendicare-managed home to be taken over under government orders: Lakeridge Health assumed control of Orchard Villa in June last year, stating that it was “directed by the Government of Ontario” to do so.

The Local attempted to reach Tendercare for comment, but received no response.

Staff shortages, turnover, issues with food distribution, and an erosion of the relationship between staff and residents seems to be endemic to outsourced long-term care—it’s the rule, rather than the exception. Pat Armstrong, a sociologist in the field of long-term care and professor at York University, has studied long-term care in Canada and around the world, and recognizes these issues as appearing time and again.

Prior to COVID-19, Armstrong’s research took her to long-term care homes run by a variety of for-profit companies across Canada that provide outsourced services: she found that in some cases, contracted-out staff were instructed not to speak to the residents, either during meal times or when their rooms were being cleaned, because it was seen as inefficient. “The employer of those workers is more likely to say, ‘Don’t have a chat, that takes time away from you moving around and doing what’s important.’”

But, as Armstrong points out, “care is so profoundly about social relationships.”

The result of these top-down guidelines is isolation for both staff and residents. The circumstances of their work makes it immensely difficult for agency nurses or PSWs to build a team rapport with the permanent staff at the facility, to build connections with the residents, and to become familiar with their environments before they are moved elsewhere.

This, in turn, can have a material impact on the nutrition residents receive, their mental well-being, and their physical health. When residents develop health concerns, it’s more difficult to communicate the issue to staff they don’t know, and for staff to give them the time, attention, and understanding they need without knowledge of the resident’s medical history and the context of their illness.

“It’s not the fault of that worker,” Armstrong emphasizes.

The fault is in how long-term care infrastructure has been built on an overworked, underpaid, and isolated workforce, many of whom are racialized women in already financially precarious positions.

Extendicare Assist’s largest client is Southbridge Care Homes, the owner of Orchard Villa, the Pickering long-term care home with the second-highest number of deaths in the province. Southbridge’s core business is to acquire and re-develop long-term care homes, but not run them.

In 2012, Southbridge entered into a long-term agreement with Extendicare to operate its acquired facilities. It then went on an acquisition spree, rapidly buying up a series of homes from existing owner-operators across Ontario, before transferring day-to-day management to Extendicare Assist. Today, Southbridge’s portfolio includes 26 long-term care homes in Ontario operated by Extendicare Assist.

Our analysis shows that the Southbridge-Extendicare combination has a COVID-19 fatality rate of 7.68 per 100 beds—a full 108 percent higher than industry average—the deadliest among all outsourcing arrangements in the province.

Watching Southbridge-Extendicare take over Orchard Villa in 2015 meant witnessing an immediate, steady decline in the quality of care provided at the home, say family members of former residents.

As with the other homes, it began with the food, says Patricia Watson. She used to volunteer at Orchard Villa twice a week, starting in 2014, and had close friends residing in the home, including her ex-husband Paul Parkes, about whom The Local has written previously.

“Then I started to see extreme lack of staff. Then I started to see infighting,” she says, describing arguments between permanent staff and agency staff. “The good people in the staff, the PSWs, the heads of nursing, the people who had to answer the CEO, were really good people. And one by one, by one, by one, they could not with conscience work there. They left. I saw constant staff turnover.”

Watson’s daughter, Cathy Parkes, saw the crisis play out until the very last day she spoke to her father in April 2020. She was standing outside her father’s window, on the phone with a PSW who was on her first ever shift at Orchard Villa.

“I said, ‘How do you think he is?’ And she said, ‘Honestly, I don’t know. What’s your father normally like? Because I don’t know anything about him.’”

“There’s your problem right there. If you don’t know that my dad’s normally up and talking and lucid, and then you see him comatose in bed and you don’t have any files to read, how do you know to manage his care?” she says. “[But] I’m very thankful to her. I don’t think it was her fault.”

Cathy’s father died from COVID-19 shortly thereafter.

Sylvia Lyon, whose mother Ursula Drehlich was a resident of Orchard Villa starting in 2013, describes witnessing the same decline Watson and Parkes describe.

“If you want to make a profit, you have to cut—and that’s where I think things fell apart, specifically for Orchard Villa. They didn’t manage directly, they have a layer of expenses, they have a layer of extra communication, lack of continuity between staff and management,” she says.

In a statement, Candace Chartier, Chief Seniors’ Advocate and Strategic Partnerships Officer at Southbridge, told The Local that, “Southbridge recently completed a Communications Satisfaction Survey of families at Orchard Villa. More than 87 percent of respondents indicated that they were happy with the level of communication they were receiving during the pandemic.”

In response to the allegations of staff disagreement and departure, she explained that “without a specific example, we are unfortunately unable [to] verify the accuracy of this claim. […] We do have a Code of Conduct and harassment policies in place in all of our homes. […] If an allegation of non-compliance is made, we take immediate action to investigate and deploy corrective measures.”

“Given that there is currently no comparative data on staff retention and turnover rates for individual long-term care homes in Ontario, we feel it would be highly speculative to make any claim about the staffing retention or turnover rates at the home. While staff turnover at Orchard Villa was higher in 2020 than in previous years, this may be attributed to policies that were implemented to prevent the spread of COVID.”

“Why isn’t this plastered on their door and forced on their website? There should be a flashing icon on their website to warn us of this.”

Lyon is the lead plaintiff in a class-action lawsuit against Orchard Villa, Southbridge, and Extendicare, led by lawyer Gary Will of Will Davidson LLP. The suit, yet to be proven in court, alleges negligence, breach of contract and wrongful death by those who run the home—claims that Will argues are bolstered by the numerous warnings and voluntary plans of correction issued by the Ministry of Long-Term care even before COVID-19 began.

Extendicare and its subsidiaries have been named in a number of class-action lawsuits since the pandemic began, the latest of which covers all Extendicare facilities and is seeking $200 million in damages. The unproven claim alleges that the company failed to adequately respond to the pandemic, and that it was negligent. Another sweeping class-action lawsuit names Extendicare among several other long-term care providers, including operators Chartwell and Sienna, and individual long-term care homes.

In 2020, complaints inspection reports by the Ministry resulted in 19 written notifications, 12 voluntary plans of correction, and two compliance orders for Orchard Villa. The number is unusually high compared to the other worst-hit homes, Tendercare (which received 4 written notifications, 2 voluntary plans of correction, and 1 compliance order) and Villa Colombo (with less than 5 written notifications and voluntary plans of correction).

“How could people in the health care business treat people so cavalierly?” Lyon says.

Candace Chartier told The Local that Southbridge “contracted the services of Extendicare Assist to manage administration, the delivery of care, and daily operations of many of its homes, which includes the use of Extendicare’s policies.”

“Since Southbridge took over ownership of [Orchard Villa],” she continued, “compliance orders have remained low […] In any instance where an Inspector has made a recommendation, the home has taken immediate action to implement changes.”

Tendercare’s website does state that the home is managed by Extendicare, but includes no apparent further detail. James Ha was in the dark about Extendicare’s history in other homes, prior notices of non-compliance, and even about the extent of Extendicare’s work at Tendercare.

“Why isn’t this plastered on their door and forced on their website? There should be a flashing icon on their website to warn us of this. It’s completely, completely negligent on the part of the Ministry of Long Term Care, and the Conservative government,” Ha says, furious. But even if he’d known, Ha may not have had the choice of turning down Tendercare—as of 2019, there were 35,000 Ontarians waitlisted for a long-term care home bed.

Responsibility for the lack of transparency lies not just with the homes, but also the Ministry of Long-Term Care. The government’s webpage that explains how to choose a long-term care home encourages individuals to read the Ministry’s report about each home. However, those reports seldom mention that a home has outsourced operations. For example, of the 26 Southbridge homes where day-to-day management is outsourced to Extendicare Assist, the reports disclose that fact for only six of the facilities.

So how do you tame a beast like Extendicare? The answer, from affected parties across the board, seems to be stronger enforcement of standards of care. While the Ministry of Long-Term Care can conduct inspections that result in compliance orders, warnings, and voluntary or mandatory management contracts, turning these regulatory steps into financial or legal consequences is rare, and requires the involvement of the police. This means, the families argue, that the homes aren’t really experiencing consequences for their actions.

The Ministry of Long-Term Care said in a statement to The Local that “Compliance is assessed through our rigorous inspection program, which ensures that every single long-term care home is inspected at least once a year.” They added that they have “processes in place for inspectors to report potential criminal negligence to the appropriate local police. […] The police would independently determine whether an investigation is warranted.”

“Together with our health care sector partners, we have been taking action to address challenges raised in Ontario’s long-term care homes by the COVID-19 pandemic—including issuing management orders, enabling the deployment of hospital staff and the use of infection prevention and control teams,” they said.

But beyond legal action, there’s the necessary question of how Canadians want the future of long-term care to look. There’s the argument in favour of eliminating for-profit homes and services altogether, or creating national standards to prevent negligence on this scale. The role of outsourcing needs to be part of that conversation.

The way COVID-19 has unfolded in long-term care homes—and devastated homes in which services are outsourced—has left families grief-stricken and incredulous. As for staff, it has taken the life out of an already strained workforce, and given them nothing in return.

The same can’t be said about Extendicare’s shareholders. The Star previously reported that the company paid $29 million in dividends to its investors over the first three quarters of 2020, while receiving at least $82.2 million in emergency wage subsidies from the Canadian government.

“As soon as I’m done, I’m out. Thirty plus years of nursing, and I’m ready to walk,” Blake says. When asked what he thought of the profits Extendicare had made in 2020, his tone was biting.

“I’m very happy for them,” he says. “It’s outrageous that they’re making this kind of money. […] Is that what we’re all doing it for? The money? Because you know, a lot of the PSWs on the ground, they’re doing it because they think they’re going to get rewarded in heaven. If you can exploit that, then good for you—if you can deal with it without feeling, good for you.”

Correction: An earlier version of this story incorrectly stated that Sylvia Lyon, the daughter of a resident at Orchard Villa, was unaware the home had received multiple notices of non-compliance in inspection reports by the Ministry of Long-Term Care. She was aware of the home’s history.