As told to Anupa Mistry

I started visiting Moss Park in 1982. It was my park. I could go and sit down all day, watching the hawks fly. This part of town is home for me, no word of a lie. But I’ll never forget the day I went to Moss Park to live. It was March 29, 2020, when COVID started.

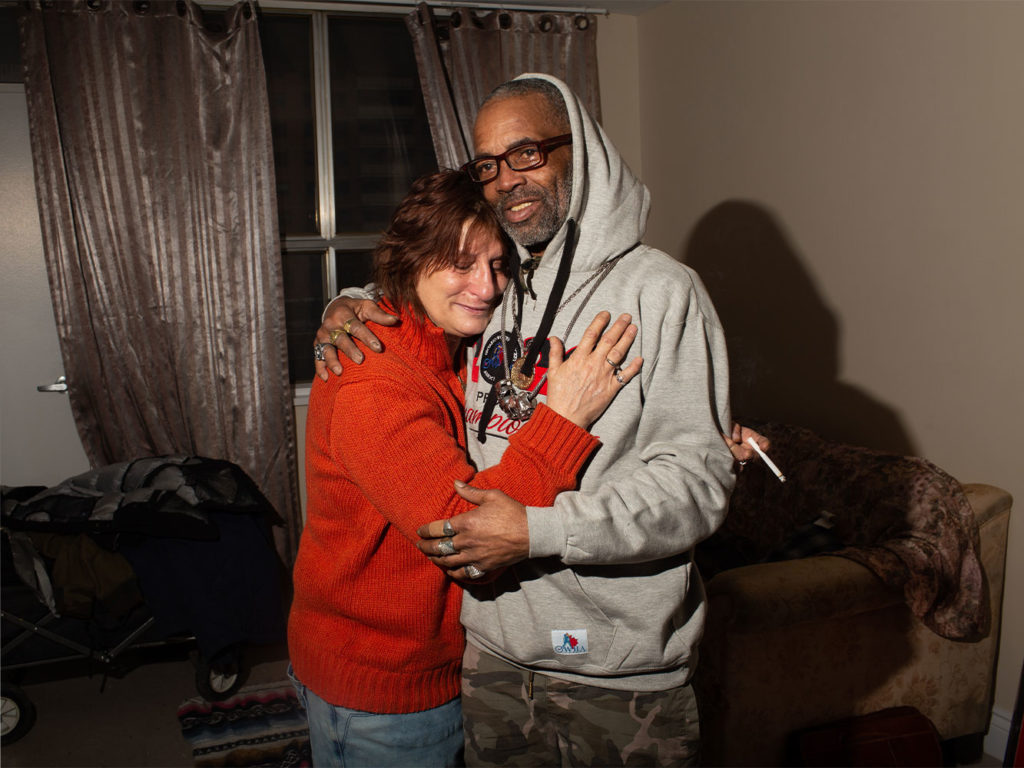

It was my girl’s idea, Michelle Plourd—she came up with it, she was everything. There was a COVID outbreak in her building, so she said, “Why don’t we make a tent over in the park?” That’s where we started. We didn’t want no interference. I just wanted to spend time with her because it wasn’t safe to come and go from her place. And I couldn’t go to my mother because she could get COVID.

It was safer in the park. It wasn’t crowded. More breeze, more everything! It was a nice set-up. I had my bike in there, an airbed. It was quiet and it wasn’t too cold because it was springtime. There was three tents first, and then more people came. Soon Moss Park was the biggest encampment in the city. There were so many people, from Sherbourne to Jarvis! Over fifty tents.

In May, I heard that they knocked down the encampment in Vancouver. That’s when I decided: I’m staying in Moss Park. I’m going to make it my home, and I’m going to make it hard for them. If you burn my home, that’s wrong—because it’s my home. I toiled to make it safe. Not for me, for us. So when the City came, I said, “I’m not leaving. I’m not going to a hotel. I’m not going to no shelter. I’m not leaving unless it’s to go from my tent straight to an apartment.”

I was born in Montego Bay, Jamaica, and immigrated to Canada in 1980. I don’t remember much about my childhood, except that I used to play soccer for a nonprofit organization. I was so good I thought I could get a scholarship.

My mom has 14 brothers and sisters. When the youngest was 17, he come to Canada to work. He saved his money and sent for someone, and then a sister came, and then they sent for the next one. By the end, all 14 came here.

I arrived in Toronto on a Friday night in March of 1980. I looked through the window and saw snow on the branches dem. Everything looked so pretty. That was up by Oakwood and Eglinton. On Saturday morning I was standing outside and I see a police car on the roadside, looking. It made a U-turn and stopped right in front of me. At that time the police car was yellow. Maybe you don’t remember? That’s what I’m saying, you’re a rookie! Anyway, they said I must go inside the car. I said, “For what? I just came here!” I refused, and the man pulled out his gun, so I go in the car. He said they got a call about someone breaking a phone booth and the description fit me. Well, I don’t even know how to use the fucking phone! Where I came from, when you called your family you had to use a calling card. At that time immigration was deporting people. They wanted to see my papers. They searched my place. I’ll never forget that.

When I came here minimum wage was… well, I don’t know if it had reached $1.50 yet! I used to pay 35 cents on the bus. I was fixing refrigerators. That was my trade for years. My uncle had an appliance business, and he showed me the trade. I also went to George Brown college. I used to do car engines too: I’m a jack of all trades!

I lived in South Regent [Park]. I couldn’t cross Dundas to go to North Regent because white men would kill me, lick with a baseball bat. One day about 10 white men beat my uncle. White people and black people was in a kind of racial thing back then.

One night in the summer, I was in my tent, smoking, not doing anything. I see this man coming from the back window, and he whispers, “I’m the police,” and I go, “I know.” He walked around, but he never come inside because him have no right without a warrant. From there the police really started to fuck around with me.

Trenchtown was the spot in the park with the most tents, by the tennis courts. I had the biggest tent, right next door to Trenchtown. People started to give me stuff and that made me more determined. In the summer we got a pool and filled it with water. It was so hot. There was ice and Gatorade. All kinds of people came through the park, and it was there for them. One morning it wasn’t there. The pool disappeared, all the drinks, and I was mad because that was for everyone. It was one of the only times I got fed up.

In July, the City came with 24-hour eviction notices and said they’re coming back with the cops the next morning. They did not offer us housing. We said, “You’ve got to give us 72 hours.” All of these people got together [14 encampment residents, the Ontario Coalition of Poverty, and the Toronto Overdose Protection Society] and we said we’re going to sue the city, and we’re going to stay. The next morning, workers came with bulldozers and trucks. I thought if we sue the city, and we have a stay, that gives us more time to plan. And it worked: evictions stopped across the city. I had my birthday party in the park that month.

In August, the police raided my tent. I got up to get a Gatorade and then I heard, “Police! Everybody get down on the floor.” I was going to get down, but when I turned around to look, a cop punched me in my face and knocked off my glasses. They were coming from everywhere—bike cops, dog cops. They had me down on the ground for more than three hours, and searched everything. They said they got a call for a gun. There was no warrant. They cut up the airbed, slashed my tent, didn’t find anything.

In September we had a protest march. It was so nice, watching police guarding us. I was happy, burning my spliff, celebrating, for all these things that we do. Hundreds of people came.

In October, we lost the case. We watched it in the park on a projection. It was still good because it put pressure on the City. We let the government know they can’t push around people. It didn’t phase me. I felt like, “We’re going to march to Ottawa! We’re going straight to Trudeau because the mayor is not doing anything!”

I got the very first Tiny Shelter in November. That little house was the nicest! It was very cold outside then, but because of those shelters people could live through the winter. I wanted us to populate and make houses that stack, but the government said we can’t. If it was Jamaica, the government couldn’t do nothing. People would stand up for their rights and say, “Let we all do that. If one goes down, all of us go down!”

I want the government to give people affordable housing and not let people die. If people aren’t taken care of, they struggle. We have a surplus of money here but look how many people are poor. We should be like Cuba: nobody is richer than each other. Look ‘pon Bill Gates: he has billions of dollars. Split it up and share it! You’re not going to die.

I applied for TCHC housing 40 years ago. But they never, ever called me until I said I’m not leaving the park. Until I was too hard to ignore. First a few of us were just living in the park, and then people came to give us food and water, and then the lawyers dem help us fight—and then I went viral! I had one goal: to fight for people living in the park, and to fight for me too.

I didn’t specifically tell Streets To Homes that I wanted to be housed in Moss Park, but I knew the place had to be right. My caseworker said he was working hard for me, but I just didn’t want to hear any bullshit. They offered me a bachelor, but it wasn’t what I needed. Another time they offered me an apartment but didn’t tell me where it was! I was in the dark.

At the end of January I found out I was getting this one-bedroom apartment, here in Moss Park. I moved in a couple of weeks after. I cried so many times because I haven’t seen my babies, my cats, in over a year. I’m happy, and I thank god. I knew it would happen but I was surprised it was so soon. There’s a pastor that’s supposed to come and bless the place.

I’m grateful, but I have nothing because the City took my stuff when I was moving in. [The housing people] said, “You don’t have to rush.” On Friday I started to move, but there was a snowstorm and I was alone. It was so cold I only made one trip. I was thinking Saturday I’d get the rest of my stuff—but when I went back nothing was there. Me and Michelle had things packed and ready to go. Everything was cleared. I had a white leather couch there, it was gone. A coffee pot. My propane, my generator. I kept my life locked up in the Tiny Shelter. My son’s baby pictures. My passport. Money won’t replace what was lost.

I wanted to be a leader because I have a strong voice. I wanted to speak for people who cannot speak. The second I leave, look what’s happening: they cleared my stuff, and they’re clearing all the little houses. I’m not there to get in the way anymore. There are a lot of people, especially older people, who have paid their dues. They deserve better.

People say I run Moss Park but nobody run Moss Park because when they’re dead and gone, or if they leave, Moss Park is still there. I want to tell everyone: We’re all in this together. I used to sit in the tent in the dark and think about why things are so hard, but I didn’t leave. If everyone is determined and said, ‘We’re not moving!,’ watch what happens! They will find affordable housing, because our lives matter.